New York City’s mayoral election is limping to such an ugly finish that it’s almost hard to pick the most distasteful moment.

Well, that’s not entirely true. There’s a clear winner. It’s former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, in an interview on a conservative talk radio station, discussing Democratic nominee Zohran Mamdani in office during a crisis as serious as 9/11. “He’d be cheering,” the host suggested. “That’s another problem,” Cuomo agreed.

But after that? Well, maybe talk of President Donald Trump dangling an ambassadorship to tempt current Mayor Eric Adams and his questionable ethics out of the race. Or maybe dopey Trump-loving billionaire Bill Ackman abasing himself day after day in a desperate attempt to drive Republican nominee — and beret aficionado — Curtis Sliwa out of the race.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not in the business of saving Ackman, Michael Bloomberg and Barry Diller money. Nevertheless, the dreary end of this race is a telling contrast to this summer’s Democratic primary.

It’s easy to see the difference. The primary was conducted with ranked choice voting (RCV), which encouraged civility and kindness. The general election is winner-takes-all, which incentivizes gloves-off aggression and all the negativity that billionaires can fund — all while giving voters less/fewer choice(s). The general election would be quite a different race with RCV. New Yorkers should make that happen next time.

Think back to the final days of that campaign. Not much in American politics feels uplifting, but this was that rare moment that seemed to exemplify what our elections could be. Mamdani and Brad Lander appeared together on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” and bicycled to joint events in all corners of the city. Candidates cross-endorsed each other; they even fundraised for one another.

Ranked choice voting made that happen. In an RCV race, candidates need a majority to win, and voters can rank their favorite candidates in order: First, second, third and so on. This is a powerful tool in races with more than two candidates. Perhaps most importantly, it ends any talk of spoilers, and encourages candidates to make a positive pitch to voters, seeking second place votes, rather than closing with extreme negativity.

The primary ended with togetherness and produced a majority winner in Mamdani. The general is a completely different story. It’s ending, predictably enough, in awfulness.

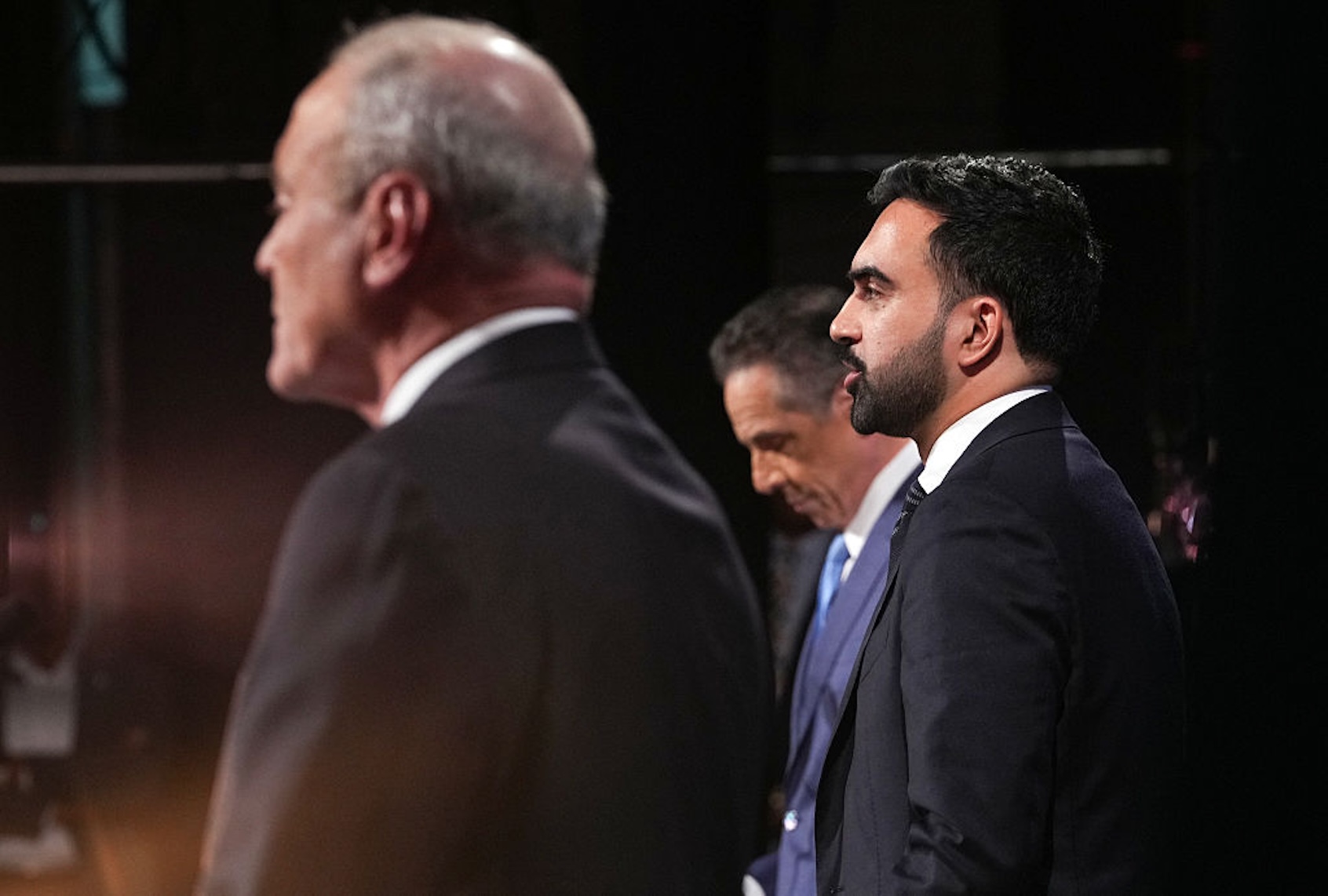

The primary ended with togetherness and produced a majority winner in Mamdani. The general is a completely different story. It’s ending, predictably enough, in awfulness. There are three serious finalists in Mamdani, Cuomo and Sliwa. This ratchets up complaints about spoilers: Adams had to be driven from the race first. Now the plutocrats are aiming at Sliwa, as if voters shouldn’t be able to make this choice themselves. Billionaires shouldn’t be shoving candidates out of the race and reducing the choices for voters.

This also encourages the kind of wild negativity we’ve seen in the last week — such as news cycles about whether Mamdani’s aunt was afraid to ride the subway after Sept. 11. But the political incentives in a race without RCV just encourage this hostility. The goal is to drive support for other candidates down, not to build up your own. Given the increasing insanity of the attacks, Cuomo’s closing argument might as well be reduced to “Mamdani will ruin New York, and Sliwa should quit the race.” Four days out from Election Day — and in the middle of early voting — Cuomo’s team posted that “A vote for Sliwa is a vote for Mamdani.”

There’s no positive vision to be seen.

RCV created an entirely different primary. In February, Mamdani polled at 1 percent. Cuomo seemed to have an insurmountable early lead. It would have been natural for the progressive candidates to try and push each other out, and decide upon one candidate to go up against the front-runner. That would have short-circuited the entire race. Voters hadn’t even tuned in yet. When they did, they liked what they heard from the newcomer. Instead of arguing about spoilers, candidates talked about real issues, like rent, housing and affordability.

Want more sharp takes on politics? Sign up for our free newsletter, Standing Room Only, written by Amanda Marcotte, now also a weekly show on YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts.

Now, without RCV, the debate is about whether it was Mamdani’s aunt or cousin who feared on the subway. It’s about spoilers, who ought to drop out, and what rewards they ought to receive from the president. It’s about how much mud can be thrown to drag the front-runner down.

It’s a case of pick your poison. Voters can have a campaign like this one, filled with negativity. It could end with the election of a mayor with less than 50% of the vote, who would then have their mandate to govern called into question by the same people who just lost. Or, they’re told, Sliwa should be forced out, to create a one-on-one race between Mamdani and Cuomo. This would deprive New York Republicans, small as they may be, of the ability to run their own nominee.

No wonder so many Americans have tuned out of politics. Imagine, instead, a race with RCV, in which Mamdani, Cuomo and Sliwa had to make the affirmative case for themselves. Candidates could join together, if they liked, via cross-endorsements, instead of having their advocates work to push folks out of the race before voters have a say.

We need your help to stay independent

We saw a taste of what that election might look like when the candidates debated earlier this month. Mamdani was asked how he would rank his ballot if New York used RCV in the general election. He said that he would rank himself first and Sliwa second. Sliwa jumped in with one of the most memorable laugh lines of the race. “Please don’t be glazing me here, Zohran,” he said, borrowing some Gen Alpha slang as the candidates, and audience, laughed riotously.

With ranked choice voting, we can have lots of choices and majority winners. We can have elections with multiple candidates that are about issues, not about who is spoiling things for whom. And we can have elections where candidates build each other up and work to appeal to everyone, rather than relying on as much toxicity as possible.

New York has made the contrast clear. RCV produces one kind of election. Plurality, pick-one contests offer another. No one need be glazing anyone to understand which approach is better for voters and our democracy.

Read more

about this topic