The last decade has seen a harlequinade of big shots, celebrities, pundits and politicians bounding across the proscenium wearing stage makeup and playing different characters successively, like Peter Sellers in “Dr. Strangelove.”

Dr. Jill Stein, the Green Party candidate, yukking it up with Vladimir Putin over dinner. Bernie bros voting for Donald Trump. JD Vance, hillbilly venture capitalist turned U.S. senator, decrying Trump before becoming his vice president, or rather his Ganymede. Kanye West, or whatever he now calls himself, being weirdly attracted to Adolf Hitler. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. singlehandedly turning Camelot into Potterville. Marjorie Taylor Greene finding sympathy for food-stamp recipients. And then the phenomenon of never-Trump Republicans.

This group runs the gamut from those who have left the GOP and burned their bridges, to those Republicans miffed with Trump because he says the quiet part aloud and acts so blatantly that the rubes might catch on to the party’s long-term grift. The crowd that runs The Bulwark, for instance, has done a reasonably creditable job in analyzing how the GOP’s traditional pre-Trump philosophies could give rise to an authoritarian contempt for the rule of law. Stuart Stevens, a former political consultant (in politics, the lowest of the low from a moral standpoint) has commendably admitted that the party’s entire stated program was a lie from the beginning.

By contrast, there is Rep. Thomas Massie, R-Ky., who has gotten crosswise with Trump over the Epstein scandal and several other issues, and who now describes his fellow Republican officeholders as follows: “Everybody in the Republican Party, with the exception of a few, are consigned to be automatons.” An accurate judgment on his colleagues’ allegiance to Trump, even if the grammar doesn’t quite parse.

But Massie remains as extreme as the Republican norm, if not more so: He thinks his GOP cohorts haven’t done enough to eliminate Obamacare, wants to abolish the EPA, likens vaccine mandates to the Holocaust, and thinks Maria Butina, the Russian spy convicted of illegally trying to influence U.S. policy, got a raw deal.

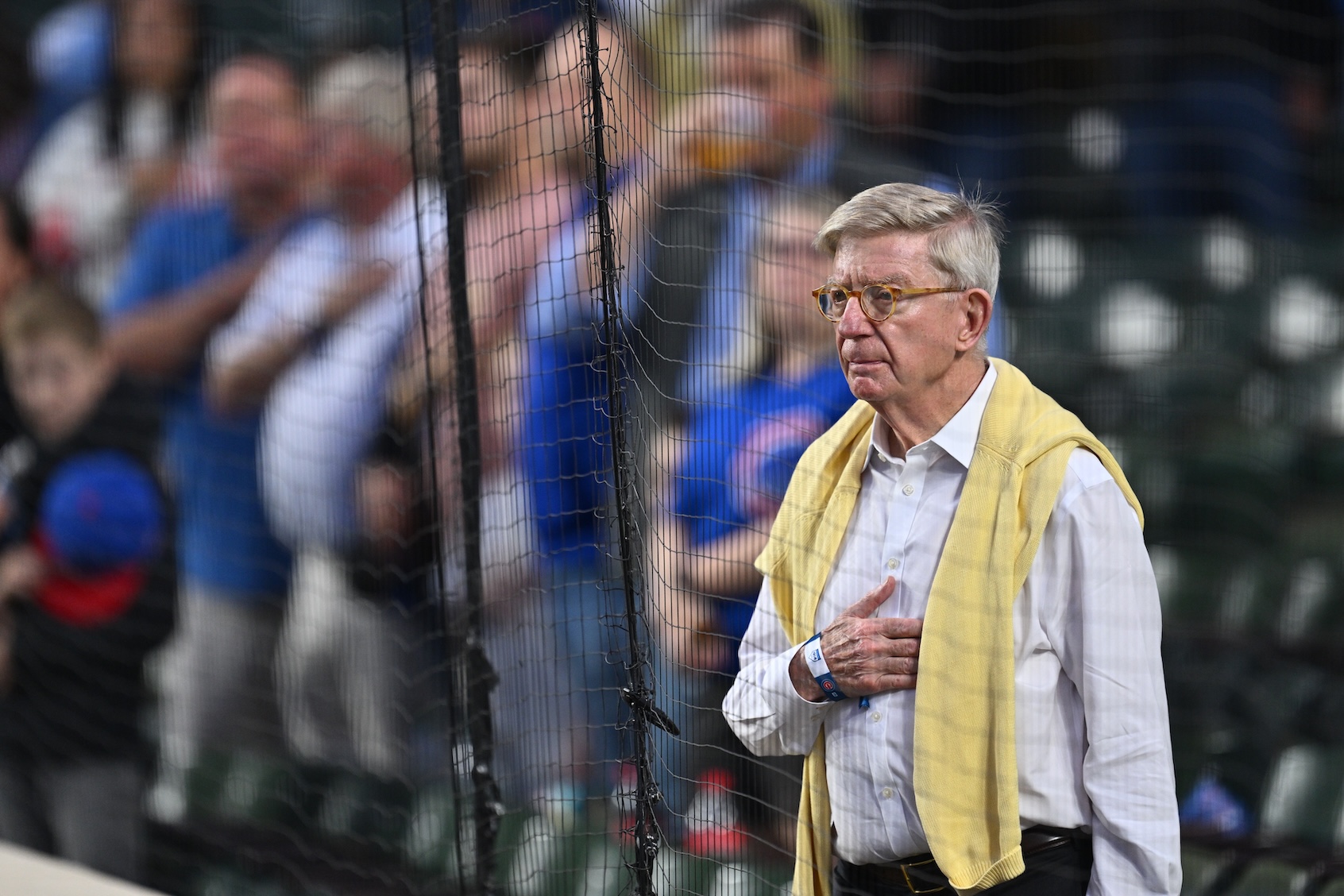

Somewhere in the middle of this spectrum of never-Trumpism we find George F. Will, who has written a column for the Washington Post since the mid-1970s, which is probably a record for a nationally syndicated opinion columnist. Even more remarkably, Will’s thought processes have resembled the French statesman Talleyrand’s description of the Bourbon kings: “They forgot nothing and they learned nothing.”

In the middle of the never-Trump spectrum we find George F. Will, who has written a column for the Washington Post since the mid-1970s. His thought processes recall Talleyrand’s description of the Bourbon kings: “They forgot nothing and they learned nothing.”

Or so it seemed until the advent of Trump, whereupon Will abandoned the GOP and declared himself an independent, parroting his idol Ronald Reagan in saying that he hadn’t left the party; the party left him. He has since written numerous pieces critical of Trump, but it is worthwhile to remember that bromide about the party leaving him — a phrase intended to convey steadfastness of character in a fallen world — when evaluating the degree to which Will has in fact liberated himself from the mental cage of right-wing ideology, whatever his nominal party affiliation.

A recent Will column offers a case in point. It begins promisingly enough, with a headline reading “A sickening moral slum of an administration.” Will describes Trump and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth as almost certain war criminals for ordering in advance the killing of any survivors of a U.S. Navy attack on an alleged Venezuelan drug-smuggling boat, and almost certain liars for their accounts of the incident.

Will cites a 1967 novel in which a German U-boat crew torpedoes a ship during World War II and then kills the survivors as a model for Trump’s and Hegseth’s criminality. There is better evidence available from the historical record: an incident when the survivors of a sinking Greek merchant ship were machine-gunned. The commander of that U-boat was duly tried, sentenced and executed after the war.

Everything Will says about the disgraceful incident is unexceptionable, and for good measure he castigates Secretary of State Marco Rubio, once a strong supporter of aid to Ukraine, for conspiring with other Trump cronies to try to compel Ukraine’s surrender to the mercies of Vladimir Putin. Ukraine is at least arguably a far more legitimate national security issue than the wanton killing of alleged drug smugglers in international waters. For good measure, Will implies (correctly) that Rubio lied about the Russians’ authorship of the Ukraine surrender demand.

But then Will spoils the effect by digressing into a jarring non sequitur:

Today’s cultural contradictions of democracy are: Majorities vote themselves government benefits funded by deficits, which conscript the wealth of future generations who will inherit the national debt. Entitlements crowd out provisions for national security. And an anesthetizing dependency on government produces an inward-turning obliviousness to external dangers, and a flinching from hard truths.

What do entitlements remotely have to do with the behavior of Trump and his co-conspirators? And the notion that entitlements crowd out national security is a falsehood. The Pentagon budget has increased under Trump and now stands at close to a trillion dollars, vastly more than the military spending of any other nation. How do Americans whose nutritional benefits have been cut, or those about to lose their health insurance, bear moral responsibility for Trump’s criminal actions?

We need your help to stay independent

Will then lurches into a tut-tutting recapitulation of the French army chief of staff’s public statement that his nation’s people must accept the risk of losing their children to protect France from an unnamed aggressor. The general’s comment was an obvious reference to Russia, likely based on Putin’s ongoing sabotage campaign in Europe and fears that it could escalate into a war.

How this is supposed to offer lessons about Trump’s actions in the Caribbean, or his willingness to bow to Putin’s demands over Ukraine, remains a mystery. That the French public may well fear for its sons and daughters should a war erupt in Europe has nothing to do with the French welfare state; there was a similar (and natural) reluctance in France and other European countries in the late 1930s when they faced the prospect of Nazi invasion — and the welfare state of today did not exist in any of those countries. Trump appeases Putin because he admires him, not because he fears that his son Barron might be killed in a war.

In a follow-up column, Will makes the case that the Constitution, judicial precedent and congressional lassitude place few constraints upon a president’s power to launch a war of aggression, and that the only remedy is a chief executive’s good character and prudent judgment. This is undoubtedly true, and Trump’s moral turpitude is obvious evidence that we must elect better leaders if we expect to avoid catastrophe. But is Will a consistent proponent of executive restraint in military matters?

He did not oppose the invasion of Iraq in 2003; indeed he was an ardent supporter of that war. Incredibly, on the eve of the U.S. invasion he opined that the war would save lives. (In the event, nearly half a million died from the war.)

Writing about the U.N. deliberations on Iraq, Will gushed over Secretary of State Colin Powell’s supposedly sober, masterly and “unhistrionic” presentation. But the visual “evidence” Powell presented was not actual photographs (unlike U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson’s photos of Russian missiles during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis), only the Bush administration’s imaginative sketches and fantasies of what Saddam Hussein’s alleged weapons of mass destruction were supposed to look like. Powell was later ashamed of being the point man for that disastrous deception.

On the eve of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Will opined that the war would save lives. In the event, nearly half a million people died.

Will also felt compelled to make snide remarks about “oleaginous” French foreign minister Dominique de Villepin, who had the temerity to question American assertions, relying instead on U.N. weapons inspector Hans Blix’s findings that there were no WMDs in Iraq. (As the world now knows, there were no WMDs in Iraq).

Will subsequently turned against the Iraq war, but only much later, after it had obviously become a quagmire. The mass torture of detainees at Abu Ghraib didn’t help. But as Justice Robert H. Jackson, U.S. prosecutor at the Nuremberg Tribunal, stated in his case against the Nazi defendants: “To initiate a war of aggression, therefore, is not only an international crime, it is the supreme international crime, differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole.” In other words, once you endorse a war of aggression, if you’re in for a penny, you’re in for a pound: Abu Ghraib was the almost inevitable fruit of an unjust action, whatever Will’s subsequent squeamishness.

Will’s detestation of Trump is certainly to be welcomed, but he is still a captive of right-wing ideology. This raises the question: Is his distaste (and potentially that of many other never-Trumpers) anything more personal revulsion at Trump’s vulgarity, and the in-your-face brazenness of Trump’s law-breaking?

Arguably, Iraq was a far greater crime than Trump’s Caribbean actions (at least so far), but Bush, Powell and company were establishment Republicans who played the traditional game of publicly agonizing over the tough decisions of war and peace, and who had a battalion of lawyers ready to argue that whatever they did was lawful and proper. Trump has no patience for any of that, and simply says, Screw you, I can do as I please. Will’s objections, based on his past writings, may be more aesthetic than principled, the product of a neatly compartmentalized mind.

Want more sharp takes on politics? Sign up for our free newsletter, Standing Room Only by Amanda Marcotte, also a weekly show on YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts.

That may help explain Will’s periodic lapses into incoherence, that is to say, into Republican orthodoxy. In 2025 (as in 2003), he still can’t resist taking a crack at the French, those decadent, socialism-coddled cheese eaters. For that matter, he takes aim at Americans receiving benefits he deems improper. Somehow I doubt he ever questioned the moral legitimacy of his own mortgage interest deduction, or other benefits not available to renters or the poor.

His diatribe about majorities voting themselves benefits is simply a paraphrase of an old bugaboo of American conservatives, that “a democracy cannot exist as a permanent form of government. It can only exist until the voters discover they can vote themselves largesse out of the public treasury.” That was coined by Alexander Tytler, a Scottish opponent of democracy, but later conservatives have attributed it to everyone from Thomas Jefferson to Alexis de Tocqueville. Will’s beau idéal, Ronald Reagan, used it frequently on the rubber-chicken-and-peas circuit. Will is addicted to such wise-sounding clichés, never mind that Tytler’s platitude is used as a means of camouflaging tax evasion by the rich.

At this point the reader may wonder why I should even bother to rebuke George Will; in his outmoded pomposity, he makes almost too easy a target. But we all make faulty political judgments: In March 2003, when the U.S. invasion began, 72 percent of Americans favored invading Iraq.

The issue is not just to admit, ex post facto, that we were wrong, but to think more deeply about why we were wrong. Any of us might make false assumptions about an issue, whether it be Iraq or climate change or the desirability of a health care bill. But the matter at hand may only be a subset of a broader ideology or worldview that creates a systematic distortion, not just about Iraq but about a whole complex of political issues.

By the time of the Tea Party and birtherism (at the very latest), it was evident that the Republican Party and the conservatism that underpins it had gone seriously off the rails. Trump was no accident; he was a near-inevitable consequence of the ethical malformation of the GOP. To turn up one’s nose at Trump and still cling to myths about welfare dependency and social rot is a failure of thought and a reliance on habit, the kind of habit usually instilled in us by parents or peers or our own comfort in an ideological bubble. It is a reflex that inhibits critical and intellectually consistent thinking.

By the time of the Tea Party and birtherism (at the very latest), it was evident that the Republican Party and the conservatism that underpins it had gone seriously off the rails.

In her much-misunderstood essay on Adolf Eichmann, Hannah Arendt emphasized not his evil but his “sheer thoughtlessness.” She said he battened onto “clichés, stock phrases” and the slogans of the Nazi state. He blanked out his mind and refused to think critically. Eichmann distanced himself not only from ordinary decency but empirical reality, “that is, against the claim on our thinking attention that all events and facts make by virtue of their existence.”

The world changes; our thinking must evolve to fit in with the facts as they emerge. We must all reexamine our beliefs in a critical and dispassionate spirit to determine whether we are apprehending reality or clinging to mental fetishes. The last word is George Orwell’s:

The point is that we are all capable of believing things which we know to be untrue, and then, when we are finally proved wrong, impudently twisting the facts so as to show that we were right. Intellectually, it is possible to carry on this process for an indefinite time: the only check on it is that sooner or later, a false belief bumps up against solid reality, usually on the battlefield.

Read more

from Mike Lofgren on politics and history