Just when you thought your opinion of the Nation of Islam (NOI) and its reality-challenged leaders couldn't fall any lower, you find yourself clearing a space in the basement of your mind. Washington Post researcher Karl Evanzz has written the comprehensive biography of Elijah Muhammad, NOI's co-founder and "prophet," and 704 exhaustively detailed pages later we know far more than we ever thought possible (or bearable) about the movement so lacking in intellectual, religious or moral underpinning that only the grinding boot heel of oppression could have produced it.

Given the book's commendable grasp, the only remaining question is how Evanzz could withstand the mudslide of murder, incest and stupidity facing anyone who tries to make sense of this mishmash religion that, for all its incoherent hatred, has brought 4 million black Americans to (something like) Islam. Reading about the weak, lethal and fanatically anti-intellectual leaders of the NOI made me want to wash my mind out with soap. This all goes double, of course, for the government counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO) agents who worked so hard from as early as the 1940s to foment both political and actual fratricide among black activists, from the NOI's chaotic prototypes to the saintly (though libidinous) Martin Luther King and on to the nihilistic Elijah Muhammad himself. Few emerge from this sordid tale deserving to hold their heads up.

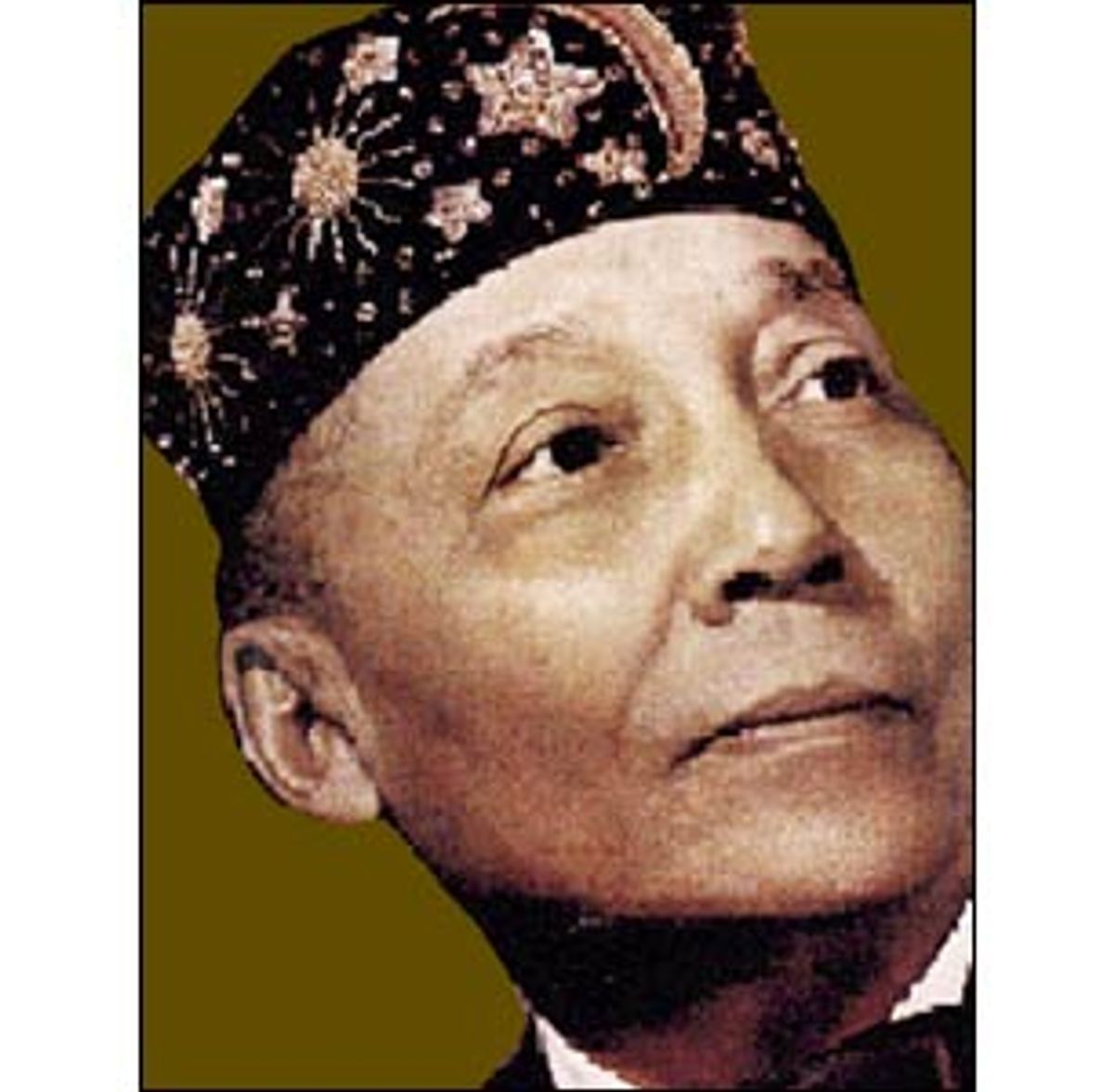

Those who know something about the Nation of Islam will not be surprised to read about the venality, hypocrisy, cowardice and megalomania exhibited by its main players -- Muhammad, along with Wallace D. Fard, Louis Farrakhan and various henchmen and competitors. Evanzz does deliver something of a surprise, though: Cast in the proper historical, cultural and international contexts, the emergence of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam seems slightly less ridiculous -- but only slightly.

"The Messenger" is really the story of what happens after a great evil ends. It's the story of America's racial chickens coming home to roost. After reading this book, any group in power thinking of oppressing another group will know the enraged and gibbering fiend they'd be loosing on their grandchildren.

Developed roughly between 1930 and 1940, the Nation's "theology" is difficult to follow. This is largely because, in that first generation after the promises of the Emancipation Proclamation had finally crumbled to dust, the movement's doctrine was made up as needed by whatever flimflam artist was proclaiming himself to be Allah that day. During this period it was clear that whites felt little anguish over their past actions toward blacks and had no intention of living peacefully and equitably with their former property. Reasonable black folks were disappointed but hopeful. Unreasonable ones were looking for revenge.

"The Messenger" is, then, the story of a life dedicated to exploiting the misery of his people for his own personal gain. Elijah, of course, was only one in a long line of con men (not all of whom were black) to recognize the hunger for release from the chronically low self-esteem and self-hatred under which many black Americans labored. The quick way out and up is to learn to hate someone else.

Muhammad, backed by a goon squad that Attila the Hun would have looked on fondly, taught a great many black people to hate and call it a religion. Given the sorry outlines of his tale, the book is most interesting as a work of history rather than the story of an individual life. Evanzz does two things that few others have dared: He deals directly with the tension between the black bourgeoisie and the lower classes of blacks in the freedom struggle, and he confronts squarely some radical blacks' outright collusion with the enemy during World War II.

Before he was "The Messenger" and a self-proclaimed divinity, Elijah Poole was a sharecropping preacher's son with a fourth-grade education, a drinking problem, a mind made gullible by suffering and a need to feel special. Born in 1897 in Sandersville, Ga., the seventh of 13 children, Poole had a childhood demarcated by his father's terrifying sermons, set against an atmosphere of Klan terror, lynchings (including a friend's), disenfranchisement and cotton-picking peonage. The young Poole read about caged Pygmies at the World's Fair and the Bronx Zoo. The wonder is that more black Americans didn't go the way of madness and race hatred.

In 1923, Elijah, by then a husband and father of two, had fled Georgia for Detroit, where he worked steadily but remained discontented, especially with the pie-in-the-sky aspects of Christianity. He drifted into black nationalist groups like Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Garvey gave voice to the frustration many lower-class blacks had harbored silently in their hearts: They were subservient not only to whites but also to lighter-skinned, well-educated, NAACP-member, linen-napkin Negroes. But here was the chocolate-brown, self-made Garvey dismissing fancy black leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois and Roy Wilkins as "'blue-veined' mulattoes who were too wedded to integration to solve the problems of Africans of the diaspora." "Diaspora" -- now there's a word a Georgia field hand had probably never heard before. The concept elevated Poole's own plight from one of personal failing to part and parcel of what he saw as an unfolding international conspiracy.

For their part, mainstream bourgeois blacks condemned Garvey as much for his dark skin as for his politics and applauded when the whites convicted him of mail fraud, only too happy to see him brought low. This theme -- the black bourgeoisie vs. the Negroid, uneducated field hands of black activism -- was continued throughout the civil rights movement, though it was rarely discussed.

It's striking that it was the working-class, often darker-skinned leaders who stressed the international context for black Americans' oppression, while middle-class blacks rarely did. Having no alternative and no reason not to, the former identified with the dark-skinned of the world, while the latter wanted the respect of and a closer relationship with American whites.

Portentously, and no doubt frighteningly to whites, bourgeois blacks and the U.S. government, UNIA's first international convention in New York in 1922 drew representatives from 25 countries, many of which the U.S. government considered enemies. The Nation of Islam would continue to expand this internationalist drive, much to the consternation of both the U.S. government and mainstream civil rights leaders. Years later, the Nation may have wanted Malcolm X dead because he told the truth on the Messenger, but the Man wanted him dead because not only was he effective domestically, but he was hooked up with undesirable Arab and African leaders.

While it was maddening for whites to demand good citizenship of those they legally considered to be less than citizens, one may legitimately ask exactly how America should have responded to movements like Garvey's and, later, Muhammad's and Malcolm's. While it was unfair to oppress blacks and call them traitors for looking for international assistance, the government still had a natural impulse to protect itself from foreigners who claim to hate the U.S.

Garvey preached a new nation in Africa for African-Americans, which he called the United States of Africa. His words rang in Elijah's ears after a day of insults and the assembly line: "Where is the black man's government? Where is his king and kingdom? Where is his president, his country and his ambassador, his army, his navy, his men of big affairs?"

It certainly wasn't in America, at least not for Garvey. Elijah, on the other hand, didn't want to relocate. He began to dream, and later to preach, of the white man's impending extinction, his self-implosion through an overload of evil. (Then as now, Muhammad's followers took in stride the ever-slipping deadlines for the death of the white man.) When the white man was extinct, the black man would rule without having to change addresses. To bring closer that day of black men dancing on white men's graves, Elijah worked actively to undermine and overthrow the U.S. government and encouraged his followers to do the same.

The lessons that both white and black America taught Marcus Garvey made a big impression on Elijah Muhammad. Garvey served five years for mail fraud and was deported back to Jamaica, discredited. He blamed not white America but his "opponents of the colored race" for his downfall. "They are light-colored Negroes who think that the Negro can always develop in this country. They also resent the fact that I, a black Negro, am a leader."

In 1959, Thurgood Marshall, the embodiment of the black bourgeoisie and mainstream movement work, would dis the Black Muslims as "run by a bunch of thugs organized from prisons and jails and financed, I am sure, by Nasser or some Arab group." Can anyone fail to see why the black working class jumped on the chance to get out from under the thumb of the "blue-veined mulattoes"? Marshall, of all people, should have known that lots of those black folks in jails were guilty of little more than the quest to survive.

The glancing light Evanzz casts on black informants and double agents is another fascinating aspect of his book. When an enraged Hoover made the destruction of Elijah Muhammad a top priority -- as he had done with Garvey -- the FBI had no trouble recruiting moles to funnel information out and disinformation in. Far more Americans, black and white, approved of Martin Luther King, but even so, Evanzz reports that 3,000 black and Hispanic agents were recruited to wreak havoc in King's planned 1968 Washington Spring Project. Who were these agents?

From the '20s through the '40s there was intense political turmoil in the black community -- much of which did not involve the mainstream civil rights movement and direct opposition to white racism. Evanzz is to be praised for bringing to light an aspect of black history that many blacks likely want to forget: collusion with the Japanese on the eve of World War II, and conscientious objection based on opposition not to war itself but to fighting for "the white man." Elijah traveled the country giving pro-Japanese sermons and exulted in the carnage at Pearl Harbor primarily because he believed it when the Japanese promised blacks "nice homes on islands near the United States" in exchange for their assistance. It is also possible that the Japanese gave him money. Elijah so hated America, he wouldn't even allow his followers to vote.

While he's not a strong writer, Evanzz is a stellar researcher, and no one interested in understanding black America -- or in critiquing it -- can skip this book. But if the only discussion it engenders is a warmed-over debate over the merits of nonviolent and violent protest, we will have wasted a golden opportunity to address more complex issues, like patriotism in the face of oppression, and repressive, exploitative hierarchies within the black community. It's easy to talk about what the white man has done to blacks. The time has come for blacks to talk about what they've done to each other.

Shares