At the college I went to, each student was required to attend the fall convocation ceremony that marked the beginning of each academic year. It was so deadly boring, though, that barely anyone did, except for my best friend Dana and me. During our freshman year we discovered a delight that we returned to witness faithfully each fall. At some point, the dean of the college, a woman who'd been there forever, would rise to address the assembled and, without fail, would work in the phrase "the turbulent '60s." Watching her mouth tauten and twitch as she said those words was something akin to seeing Emily Post forced to spew obscenities in public. It was irresistible.

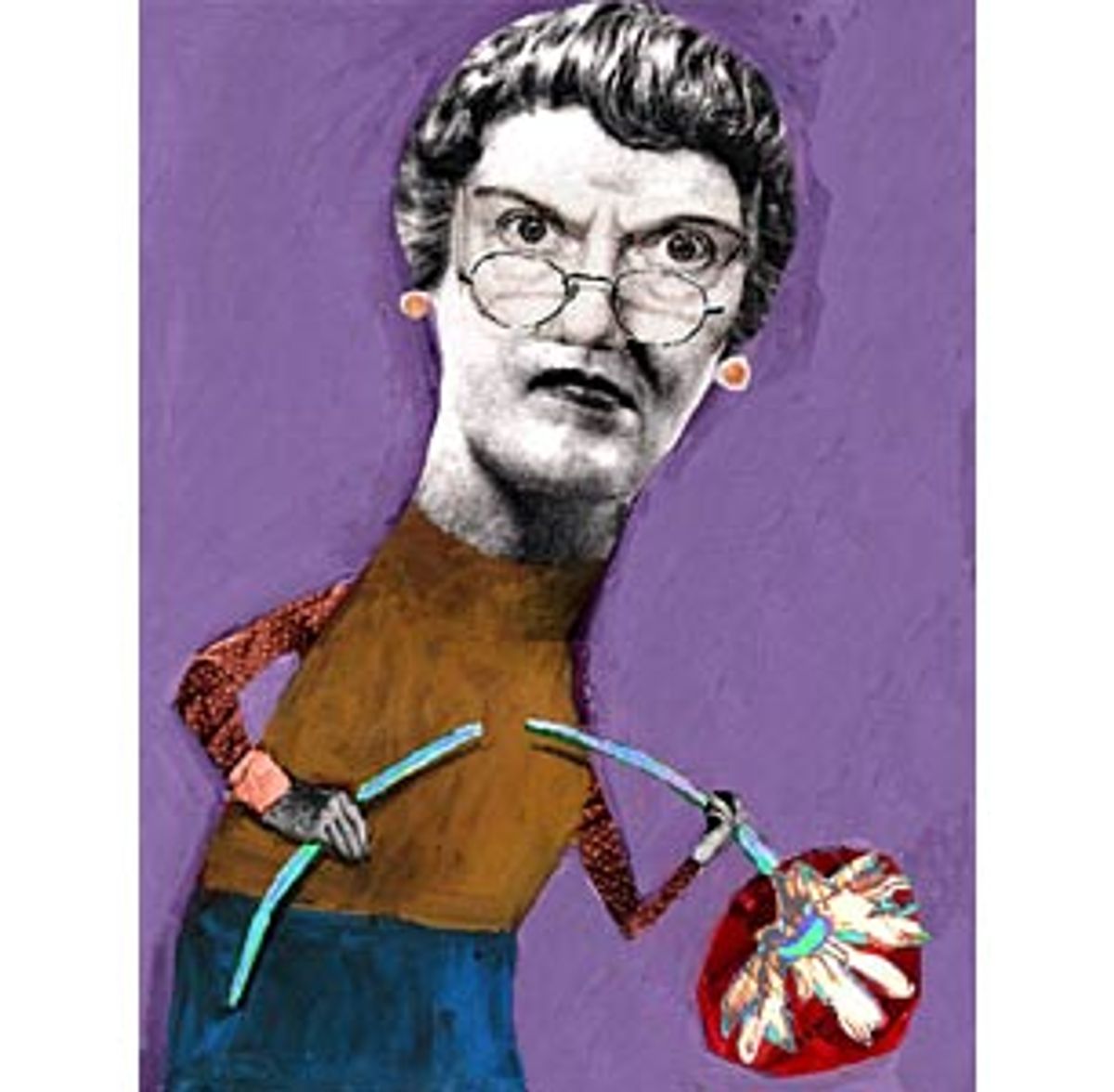

In the spirit of my college dean, Gertrude Himmelfarb's new screed "One Nation, Two Cultures" can be seen as one prolonged, taut-lipped twitch.

As well as being professor emeritus at the graduate school of the City University of New York, Himmelfarb is also one of the most widely respected scholars of the Victorian age, which she has written about in books like "Victorian Minds" and "Poverty and Compassion." Such is her formidable reputation that even liberals acknowledge it. Having stuck only the daintiest toe into the waters of her erudition (an op-ed here and there, a few pages of "Poverty and Compassion"), I must say, after having waded through this shallow but stagnant pond, that I hope her other work does something to justify her repute.

The intellect on display here is about the caliber of the village biddy who sticks her blue nose into everyone else's business, offering opinions nobody asked for about how everybody else should live. Like "99 Bottles of Beer," the tune Himmelfarb sings throughout "One Nation, Two Cultures" is repetitive and seemingly endless, and you always know exactly what's coming next. It's that golden oldie, top of the pops on the conservative hit parade for the umpteenth era in a row, baby! -- "America Is Going to Hell in a Handbasket (And It's All the Fault of the '60s)."

What did conservatives do before they had the '60s to blame? It's been such a boon to them that, secretly at least, they must be grateful for it (the way liberals have always been grateful for Nixon). When Himmelfarb writes, "Whatever cultural revolution America experienced in the 1920s or before, it was a faint foreshadow of what was to follow," she's using a Saturday-afternoon serial technique, keeping us hooked before unveiling the dastardly scheme that Ming the Merciless has in store. She doesn't take long to get to the wicked plot: the destruction of the Victorian virtues of "work, thrift, temperance, fidelity, self-reliance, self-discipline, cleanliness, godliness" (in her view, America's traditional strengths) by the Kryptonite of the '60s.

Himmelfarb assigns the era just the legacy you'd expect: the "social pathology" of "crime, violence, out-of-wedlock births, teenage pregnancy, child abuse, drug addiction, alcoholism, illiteracy, promiscuity, welfare dependency." And that's just a warm-up:

The loss of parental authority, the lack of discipline in schools (to say nothing of knifings and shootings), the escalating violence and vulgarity on TV, the ready accessibility of pornography and sexual perversions on the Internet, the obscenity and sadism of videos and rap music, the binge-drinking and "hooking up" on college campuses, the "dumbing down" of education at all levels -- these too are part of the social pathology of our time.

"One does not have to be nostalgic for a golden age that never was to appreciate the contrast between past and present," Himmelfarb writes, but nostalgic is exactly what she is. Implicit in all conservative hand-wringing about the sorry state of our culture, in whatever era that hand-wringing has appeared, is a longing for some lost golden age. But when was this paradisiacal era? If you started with "One Nation, Two Cultures" and worked your way backwards through all the similar tomes that have appeared in the last hundred years, it would be like traveling through an infinity of mirrors, each reflection leading you farther back without ever reaching an endpoint.

If nostalgia is the first major component of the fantasy Himmelfarb has constructed here, disease is the other. "One Nation, Two Cultures" is rife with references to it: "More recently, we have confronted yet other species of diseases, moral and cultural"; "In its most virulent form this 'decay' manifests itself in ... 'moral statistics'"; "Affluence and education, we have discovered, provide no immunity from moral and cultural disorders"; "Civil society has been described as an 'immune system against cultural disease,' but much of it has been infected by the same virus that produced the disease."

Yearning for an idealized mythical past while vilifying the "diseases" of contemporary culture inevitably results in isolation from that culture. By the end of the book, Himmelfarb is identifying herself as a political dissident, abstaining from what she views as the culture's dominant, corrupt values. Yet she won't cop to the fact that this abstention also means that she has disengaged from the culture. Himmelfarb is absolutely right when she says that dissidents may be more active members of a culture "precisely because they find themselves in a position of dissent." The trouble is that, applied to the author of "One Nation, Two Cultures," this definition of "dissident" will not hold. Everything about this book, from Himmelfarb's prim, disapproving tone to her condemnation of Americans' growing refusal to attach shame to the choices people make in their private lives, reveals someone profoundly out of touch with her era. In order to oppose an idea or an epoch, you must first give it its due, and Himmelfarb simply will not.

The lists that dot this book, and the associations made in those lists, tell the story. "What was once stigmatized as deviant behavior," she writes, paraphrasing Daniel Moynihan, "is now tolerated and even sanctioned." Himmelfarb goes from a perfectly reasonable example of this -- the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill that swelled the ranks of the homeless -- to "divorce and out-of-wedlock births," events she describes as also "once betokening the breakdown of the family ... now viewed more benignly." Who but the most extreme among us would be willing to characterize divorce and children born outside marriage as examples of deviant behavior? In another passage she praises policies that have reduced "the incidence of crime, welfare, out-of-wedlock births, and the like" (emphasis added). Who but a fanatic would equate welfare or a child born outside of wedlock with crime?

Himmelfarb tells us that we are living in a world where privacy and decency are not just outmoded but ridiculed. But her conception of "privacy" does not include sexual relations which, she is quick to point out, are never a private matter. Like a busy little seamstress with a back order of scarlet letters, Gertie devotes herself to branding whatever behavior she thinks is destroying the fabric of society: extramarital sex, single parenthood, abortion, divorce. And the fact that many Americans would laugh at that notion only makes her needle and thread fly even faster.

In her preface, Himmelfarb claims to have taken "special pains" to document her arguments with "the hardest kind of evidence, quantified data." Later, however, she concedes that "I believe there are other sources of knowledge that are more compelling than numbers" and that "Statistics can be faulty and polls deceptive, and neither should be taken too literally ... but used in conjunction with other kinds of evidence ... they have been invaluable in establishing some hard facts and correcting some common misconceptions." What this means is that she's willing to twist the data to match her theories. One of her favorite strategies is to imply a causal relationship between two different facts when no such relationship has been established. Thus we read that the rise of employed women parallels the rise in the divorce. And that the kind of people who go to church and stay married live longer than people who don't. (Despite how she makes this sound, there's no evidence that divorce or agnosticism cause early death.)

For someone who is willing to allow that common sense and anecdotal evidence are legitimate sources of knowledge, Himmelfarb ridicules those who dispute the conclusions she reaches from her statistics, including those who have argued that the actual experiences of nontraditional families may provide more truth than the statistics of social science. What does your experience tell you about the assertion that you'll live longer if you go to church? Or about the relative health of married and divorced people? I have known a great many people whose parents were divorced, and without exception they were all far happier than even the grown children of people who persisted in marriages that made them, and their children, miserable. (If Himmelfarb is concerned about the reputation of marriage, she should talk to people who've been exposed to lousy ones.) What does it do to your health, physical as well as mental, to stay in a situation like that? It's not unreasonable to suggest that being in a happy marriage may promote longevity -- but that doesn't prove that being trapped in an awful one will do the same.

Himmelfarb castigates the English sociologist Jeffrey Weeks for saying, "For many people today family means something more than biological affinity." Where does that leave the friends who are as dear to us as siblings, or the friends of our parents (or our friends' parents) who, when we were growing up, treated us as if we were their own kids? On my wedding day, my father's best friend, a man I've known since I was born as my Uncle Marty, walked up to me, took my face in his hands, kissed me and said, "I was at your parents' wedding, kid, and I intend to be at your kids' weddings." The love I felt for him then (and whenever I remember that moment) couldn't have been any dearer if he'd been my blood relative.

These are the realities of our lives that Himmelfarb's doctrinaire insistence on rigid, traditional forms of family and behavior (she is in favor of making divorce more difficult) would deny. Himmelfarb is like those people you used to run into who insisted that they weren't against interracial marriage but merely "felt sorry for the children." Her pompous insistence that we restore the outmoded stigmas attached to things like divorce is the sort of thing that causes at least as much misery as divorce itself.

Himmelfarb's remove from the realities of most peoples' lives would be laughable if it wasn't so insulting. Conceding that some single mothers must work, she writes, "but married women who work to supplement their family income may decide to forgo the amenities provided by that additional income." Amenities? The married working women I know aren't working for amenities but for necessities. How can someone who extols the virtues of family be so ignorant of what it takes to sustain a family today? And why should working mothers swallow this blinkered insult from a woman whose professed dedication to stay-at-home mothering apparently didn't impede her own career as an academic and a writer?

Himmelfarb is so intent on blaming the changes in traditional family structure on the '60s that she never considers the economic reasons behind those changes. (Those reasons include the decline in well-paid, staple jobs as businesses have increasingly turned to using cheap foreign labor.) Himmelfarb does offer some hope, though, for families who might need to supplement their incomes: Child labor. "Nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century accounts of working-class life are replete with stories of children laboring part-time and contributing their meager earnings not only willingly but proudly to the family," she writes. Child labor, she tells us, would deter the destructive effect of "children commonly receiv[ing] allowances from their parents to be spent for their personal satisfaction."

Here again, Himmelfarb simply ignores the economic realities of labor. According to her, today's working women are merely looking for "amenities," while the working children of the 19th and early 20th centuries proved themselves good little doobies by "proudly and willingly" contributing to the family income. Funny, I've never heard those lofty ideals espoused by my father, who as a schoolboy in the Depression commonly worked from the end of the school day to midnight delivering groceries because his family needed the money. And I doubt if I'd hear such ringing tales of civic virtue from his contemporaries who were in the same position. They wanted to save their own children from this kind of drudgery.

As with all this moaning and groaning about the decay of society, it's both inevitable that Himmelfarb gets around to the "diseases" of popular culture and predictable that she has no idea what she's talking about. She makes the now-familiar mistake of identifying "The Basketball Diaries" as one of "the movies that so eerily prefigured the Littleton school massacre," obviously referring to the clip endlessly repeated on the TV news in which a black-jacketed Leonardo DiCaprio shoots up a classroom. Never mind that the movie -- released before DiCaprio became a star with "Titanic" and "Romeo and Juliet" -- was a flop that played mostly in urban art houses, and that the sequence is a fantasy that occupies less than a minute of a film whose subject is drug addiction. (How come Leo hasn't inspired a wave of high school junkies?)

It goes without saying that the right to an opinion includes the right to an uninformed one. But for far too long the pronouncements of academics and politicians and other "experts" who have no understanding of popular culture, no notion of the ways in which audiences actually experience movies and music, have been accepted as unimpeachable. "The obscenity and sadism of videos and rap music," says Himmelfarb. Crap, say I. Gertrude Himmelfarb couldn't name three rap songs; she couldn't name one song currently in the top 10 and couldn't tell Jay-Z from Q-Tip if her life depended on it. (Even the phrase "rap music," instead of "hip-hop" tells you how little she knows.) For someone with a reputation for being so learned, she seems never to have learned something most people find out early on: If you have no experience of the subject at hand, the smart thing to do is shut the hell up.

It just never occurs to Himmelfarb that the courteous and decent thing to do is to shut up when it comes to matters about which she has no knowledge or that are none of her business. In her view, there are those who need to be told and those equipped to do the telling. Near the beginning of "One Nation, Two Cultures" she quotes Adam Smith's observation that the well-to-do may be able to safely indulge in vices that would be ruinous to the lower classes if "all the more difficult to resist because they came with the imprimatur of their social and intellectual betters." Then, a few pages later, Himmelfarb bemoans the "loss of respect for authority and institutions" as one of the signs of societal decay. But just as she never gives any reasons why the well-to-do should be regarded as the "intellectual betters" of the lower classes, she never tells us why authority and institutions automatically deserve our respect. The notion that authority has to earn respect never occurs to her. Has she never had a stupid boss, never encountered some rule that made no sense? And just where has blind respect for authority ever gotten us? Certainly not to nationhood.

That's one reason I'm deeply suspicious of Himmelfarb's calls for a return to "civility." I have yet to hear that word used by a contemporary conservative in a way that didn't make me suspect that what they were talking about was actually servility, a world where everyone knows his place and acts according to a single accepted -- or enforced -- standard. Himmelfarb seems greatly threatened by any questioning of what she sees as self-evident standards of acceptable behavior. And so she writes to close questions down, to deny any mysteries or complications in American life that cannot be solved or contained by those standards.

It's not just the obvious people who don't fit her vision of a civil society -- people who choose not to marry or who choose to have kids outside marriage or to not go to church. There are whole spectrums of our national experience and expression that her narrow vision of America cannot admit. Himmelfarb's is not a country that would find room for the utopian yearnings of the transcendentalists; the search for freedom in Huck and Jim's journey down the Mississippi; the simultaneous desire for communion and declaration of individuality you hear in Ray Charles' or Elvis Presley's explorations of American music; the breezy disrespect that has always characterized American comedy; or the casual, cheerfully cynical and deeply anti-elitist tone that most of us would recognize as our collective native character.

Finally, "One Nation, Two Cultures" betrays a deep discomfort with the idea of democracy itself. I don't mean that Himmelfarb would prefer a dictatorship, but the idea that democracy is strengthened and not weakened by allowing people to make personal choices that some of us may find deeply distasteful clearly drives her crazy. And surely, it can't be just liberals who are bothered by the intrusiveness she espouses. For all of her talk about conservatives being dissidents within the prevailing culture, there must be conservatives who feel as if they are dissidents within their own party, like a woman interviewed on CNN before the Iowa caucuses, a former Republican who was voting for Gore or Bradley because, she said, she was sick of being judged by the Christian right.

Himmelfarb tells us that "the Republican Party is still dominated by a largely secular business community and by pragmatic, nonideological politicians," but surely they have ceded the upper hand to the fundamentalists and ideologues. Is it any coincidence that the death on New Year's Eve of Eliot Richardson -- the former attorney general who resigned rather than follow Nixon's directive to fire Watergate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox (that dirty work was done by that great respecter of authority Robert Bork) -- passed almost unnoticed? What place would there be in today's Republican Party for Eliot Richardson, or for that matter what place is there for the conservatives who defined themselves in that vein?

Implicitly, they too are the people Himmelfarb judges and finds wanting. Conservatives (with some justification) used to complain that liberals had unreasonable expectations of people's goodness. But unreasonable expectations are at the heart of the folly of what Himmelfarb espouses. She stands for a strain of conservatism demanding a level of virtuousness that both common sense and basic understanding of human nature will tell you is unreasonable.

Himmelfarb says that we live in an age of people reluctant to make moral judgments. Let me appease her by offering one. It is morally obscene to propose, as she does, the sacrifice of people's happiness and even their lives in order to "raise standards."

"A moment comes and if you wish to look upon yourself as human you take some action," says a character in Alan Furst's novel "Dark Star." Himmelfarb prefers principles to action. But nowhere does she own up to the consequences of those principles. We can outlaw abortion -- but if we do, young women will maim and kill themselves trying to rid themselves of unwanted pregnancies. We can babble on about the perils of "value-free" sex education -- but kids will experiment sexually with or without information that might save their lives. We can make divorce more difficult -- but people will grow bitter in loveless marriages and pass on a deep suspicion of the institution to their children. We can insist that private charity must replace government assistance -- but people will lose their homes, will starve, and some will die.

This is not an alarmist vision, but the perfectly foreseeable result of the standards Himmelfarb endorses. If human misery and even death are an acceptable price to her, she should have the guts to say so. Then we can see whether the principles she upholds are those of a fool, a damn fool or a scoundrel.

Shares