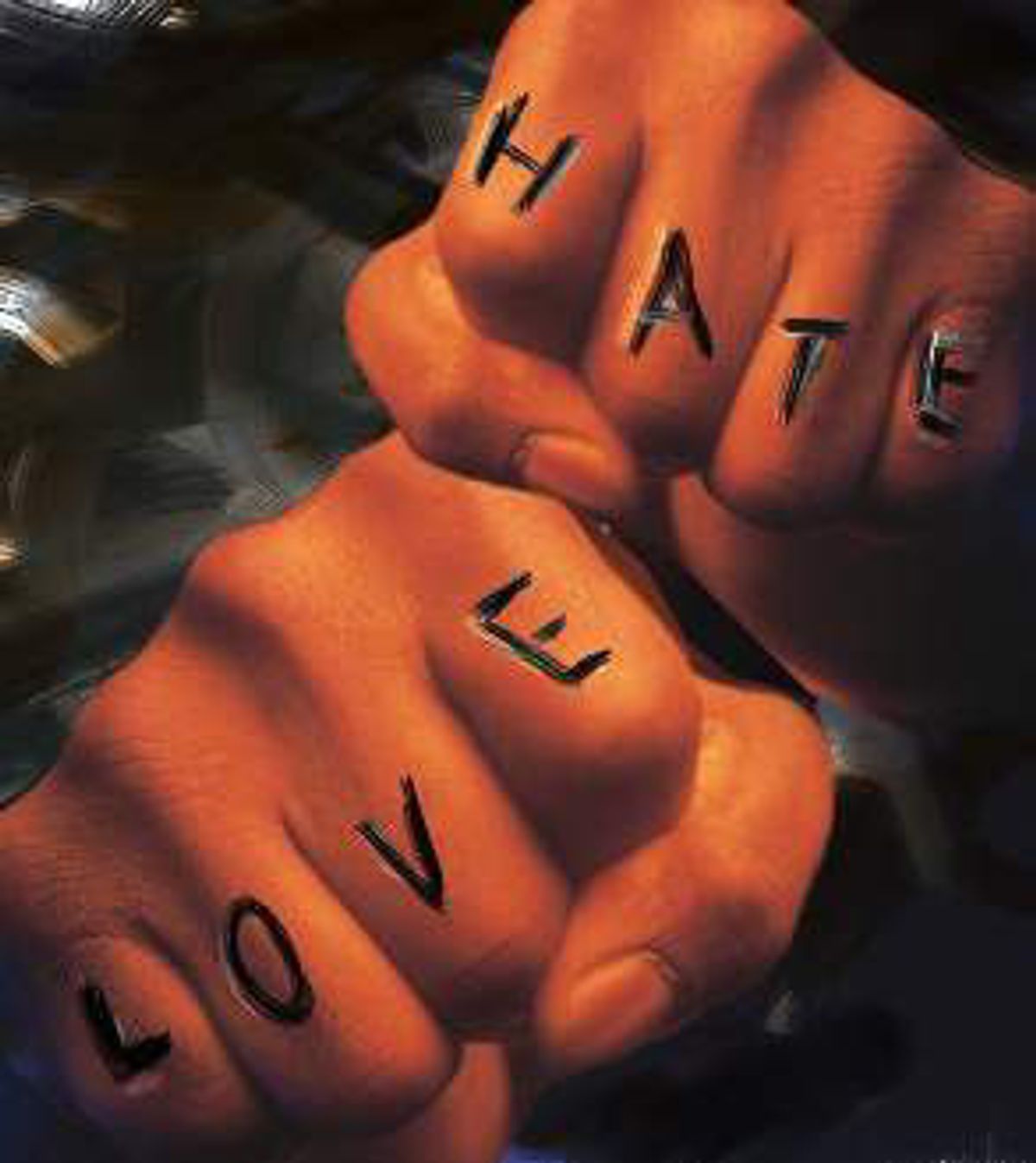

In 1986, David Blumenfeld was shot by a Palestinian terrorist in the Old City of Jerusalem. The bullet missed his brain by half an inch. Blumenfeld, an American rabbi who was visiting Israel to plan a new Holocaust museum in New York, survived the attack, recovered and returned home to his family. His daughter, Laura, then a student at Harvard, wrote a poem for an English class, the last line swearing revenge for her father's suffering: "This hand will find you/ I am his daughter."

In the years that followed, Laura Blumenfeld, who was raised to be sympathetic to the Palestinians' plight, worked abroad with Palestinian and Israeli kids, got a master's degree in international affairs and became a staff writer at the Washington Post. She fell in love with her childhood crush and married him. She was looking forward to having a baby.

But her poem was more than an outlet for fear, despair and youthful rage. It was a promise. During her newlywed year, Blumenfeld returned to the Middle East to find the man who shot her father. Twelve years after the shooting, she still wanted revenge -- a strange kind of revenge not easy to distinguish from forgiveness.

She wanted to shake the shooter by the collar. She wanted him to know that "you can't fuck with the Blumenfelds." She wanted some acknowledgement from the shooter of the wrong he had committed, of her father's humanity, his suffering and her family's powerlessness to prevent it. And she wanted "to see what we had in common." In "Revenge: A Story of Hope," a book that is alternately investigative and delicately personal, comical and gravely riveting, Blumenfeld recounts her year in Jerusalem and the West Bank in pursuit of her father's assailant, and the remarkable events that ensued after she met him. The terrorist, Omar Khatib, a member of a Syria-backed radical faction of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, was locked up in an Israeli jail for his crime. The only way Blumenfeld could contact him was by sneaking letters through his family.

Introducing herself to the Khatib clan as simply "Laura," a journalist writing about revenge, Blumenfeld began a relationship with the family, one that blossomed into a warm friendship that involved numerous visits to their house in Kalandia near Ramallah in the West Bank, mutual favors and lots of hot tea. When she first met them and they mentioned "some Jew" that their son had shot, the Khatibs laughed.

In light of the violence engulfing the Middle East right now, it would not have been surprising if Blumenfeld had simply wanted to repay harm with harm -- or if she had wanted to do so for religious or political reasons. The Blumenfelds are Jewish and Omar Khatib is Palestinian; the Jewish state and the Palestinians are locked in a bitter, bloody war. But one of the most striking and significant things about "Revenge" is that Blumenfeld's quest had nothing to do with politics. Blumenfeld's own politics are clearly dovish: In a letter she sends to Omar, Blumenfeld writes, "[My father] supports and likes the Palestinians. He taught this to his children ... this is what he said: He thinks you have been wronged by Israel in your life. He believes you went through hell, as did your brother, Imad, and your parents ... He respects your ideology and does not want to argue politics."

To Blumenfeld, then, it wasn't a "Palestinian terrorist" who shot her Jewish father -- it was a human being who shot her "daddy." Her longing to take revenge -- if you can call it that -- was not as a Jew, but as a daughter. It's obvious how important this idea is to Blumenfeld; a good chunk of the book describes her relationship with her divorced parents and the painful fracturing of her family. In her exploration of revenge, Blumenfeld delivers a rich portrait of a thoughtful, conflicted and curious avenger.

In the course of the book, Blumenfeld meets Sicilians, Albanians and a grand ayatollah in Iran in an effort to learn about different forms of revenge. But one never quite believes that Blumenfeld, a mild-natured and seemingly content young newlywed, ever wants to actually harm the man who tried to kill her father. Blumenfeld frames her cross-cultural exploration of revenge as part of her personal quest, as if she were trying to make up her mind which type to choose. This isn't convincing: the passages about other cultures' vengeful acts, both monetary and bloody, are illuminating and interesting, but they don't seem to play much of a role in Blumenfeld's personal odyssey.

Indeed, it's debatable whether what Blumenfeld achieves actually constitutes revenge at all. She argues that there are many different types, of which she chooses "constructive revenge." (Note: Those who don't want to know how the book ends should skip the next two paragraphs.) In the book's dramatic finale, during Omar's appeal to be released from prison on the basis of a deteriorating medical condition, Laura stands up in court and reveals her identity -- to the gasps and cries of Omar and his family (as well as the perplexed Israeli judges). She declares that he promised to never hurt anyone again and says that she and her father believe he should be released. Shortly after, Omar apologizes and swears to forgo violence. Is this "revenge"?

Blumenfeld's quest is both morally complex and dauntingly ambitious. When Blumenfeld and Omar begin to exchange letters as journalist and subject, she encounters an unyielding, impersonal ideological wall. "If you saw [David Blumenfeld] today, or met his friends/family, what would you like to tell them?" Laura writes. "I've told you, what I've done is not personal," Omar replies. "You have to see it as part of our legal military conduct against the occupation." By the end of the book, Omar's political views may not have changed, but he seems to have. In a letter to Laura's father that he keeps on a shelf in his study, Omar writes, "God is so good to me that he gets me to know your Laura who made me feel the true meaning of love and forgiveness." It's Blumenfeld's patience, love for her family and willingness to listen even to those who harmed her family that eventually brings her -- and the man who shot her father -- to a place of understanding and even peace.

Blumenfeld spoke to Salon from her home in New York City.

You write in the book that you wouldn't have wanted revenge if your father had died. Why is that?

One of the things that I learned about revenge was that it's often the smaller slights that people seek revenge for. If my father had been killed, I would have been too broken to do anything, really, except to believe that God would take care of the killer. That's why people who are devastated often turn to God.

Like the families of the other tourists who were killed by the same gang of militants -- who were arbitrarily shooting tourists in revenge for America's bombing of Libya -- that shot your father. But the other families didn't seek revenge at all.

And I think the reason why we seek revenge for smaller slights is because we think it's possible to achieve revenge. It's more realistic to think that you can get back at the jerk who insulted you publicly at the staff meeting than the gang of drug dealers who carjacked your wife inside of your Toyota. How really could I avenge a murder?

In the book, you put your hand around a gun. Did you want to shoot Omar?

No, and also that kind of crime would be overwhelming and I would be too terrified of the criminal who committed it. So, interestingly, it was the consequence of my father's injury that made me feel like it was a blow that I could return. Machiavelli said, "Men should either be treated generously or destroyed, because they can take revenge for slight injuries -- for heavy ones they cannot."

You had just gotten married. You really disrupted your life in pursuit of Omar. Why?

I drove my husband crazy about it. And I questioned it all the time. But I decided that this was my last opportunity. Before I started a new family, I had some unfinished business with my old family. I had to look back before I could go forward. But, boy, I questioned that decision all the way through.

Was this about you or about your dad?

It was about family. Revenge helps answer the question, who are you? You are what you're willing to avenge. I wanted to answer the question: Were we a family who stood up for each other or not? Not when it happened. My father was alone when he was shot, my mother didn't come to him. It was a way of asserting our family's identity. Many times I thought about giving up. My husband, who is a lawyer and very much a man of the law, was the one who encouraged me. He felt that this man might not have killed my father, but the intent was there.

This was about the intent.

Yes. But every day I had to go to the Khatibs' home, I would just fantasize about getting away.

What was it like to meet his family for the first time and hear them talk about what Omar did to your father?

As I listened to them laugh and smile and smirk about my father being shot, they were serving me hot glasses of tea, one cup after the next. And I remember swallowing the tea and feeling like I was swallowing all this heat and rage and keeping it down. On the outside, I took notes and nodded and tried not to show any sign of what I was feeling. But on the inside I was seething. My heart skipped beats. I remember feeling palpitations, and I thought, "That's OK, because they can't see my heart." But my forehead was so tense, it felt like it was buckling from the weight of the tension. I kept lifting my hand to wipe away the lines because I thought they'd see the truth written across my forehead.

How did it feel to spend time with the family and get to know them?

I was shocked that I actually found the man. A bullet came at my father and I tracked it down to its source. When I returned to Jerusalem during the years after the shooting, I would wonder about who he was walking down the street. After so many years of wondering about him, and so many months looking for him, I was shocked that I was actually sitting in his living room with his mother and his nephews and his brothers. It was fear and shock and nervousness.

But as time went on, I felt more and more guilty because they came to like me and welcomed me into their home and into their family. Every time I wanted to be in touch with Omar, I had to go through them because he was in prison. It wasn't like I could just drop off a letter like I was going to a post office. I had to sit with the family for at least half a day and pass the time with them. That involved looking at wedding albums and going upstairs to visit the bird coop on the roof and playing with their dog when it had puppies. Sometimes I got so caught up pretending that I liked them, sometimes I wasn't sure if I was actually pretending anymore. It was very confusing.

Did you feel guilty about deceiving them?

Oh yeah, I always felt guilty about that because it was never a part of my plan.

What was your mission?

The question that I asked myself that year was, can I make my father human in the gunman's eyes? And I thought that the only way I could do that was by tricking him. He would come to know me and to like me, or come to know us, meaning me and my father, and like us, only if he didn't know who we were. I needed to erase myself, make myself invisible in order to be seen. That I felt OK about. But dragging his family into it was never part of the plan, but I had to by necessity because he was in jail and unreachable.

How dangerous were they? What did his family do?

I never knew what they were capable of or what they would do when they found out who I was. But I knew that they were not only members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), which was a hard-line radical faction in the Palestinian national movement, but they were also active in military operations. Pictures of the brothers posing with Abu Jihad and all these famous guerrilla leaders, many of whom Israel has assassinated over the years, were the living room decorations. There wasn't needlepoint up on the wall. And one brother was a member of Force 17, which is Arafat's crack military unit. Another brother was deported to Jordan for his activities and then was jailed by the Jordanians for the Black September uprising where Palestinians tried to take over Jordan through violent revolt. And the third brother was Omar, who tried to kill my father.

Their house was also the last house on the edge of town. There was no traffic there. It was like on the edge of civilization, literally it was on a precipice overlooking this barren gorge that stretched all the way out into the desert. Completely deserted, no one could hear you there. It was an isolated compound of family apartments that were all connected. It was horrible, when I describe it, I think, "Oh my God, I did that!"

What was it like when you and your father returned a month ago?

It was surreal because we were surrounded by terrible violence which was just escalating every hour while we were there. During the time that we were inside the family's home, just up the road an Israeli tank fired a shell at what they thought was a militant leader. It turned out to be his wife and three kids in a pickup truck. There was shootings and bombings all around us. But inside this home, it was this sort of cocoon, and there was this other reality. My father and Imad, the brother of the man who put a bullet in his head, were miles apart ideologically, yet they were able to relate on some level, just as brothers. My father's one of three brothers and he listened to Imad talk about Omar in prison and he thought, "You know I would do the same for my brother." It's not to say that they could overcome all obstacles; they speak different languages, they come from different religions, they're part of two nations that are at war. But they were sitting there smoking a hookah pipe. My father seemed to even like it. I was sitting there whispering, "You don't have to, Dad, you don't have to." He took a drag on their hubbly-bubbly and exhaled heartily.

It's remarkable because when you visited with the family in 1998, it was before Barak's election and then during his term. The prospect of peace was still there. Just a month ago, when you returned, the situation was so much worse. Omar's family hadn't changed their attitudes toward you?

They were afraid. They were concerned about what the neighbors would say. There's tremendous pressure in the community to close ranks. Certain people would accuse them of being treasonous by hosting Jews.

For me, the thing that was so incredible was that the first time I went to their home, they talked about, "Some Jew. Who did he shoot? Some Jew." The first time Omar talked about my father, he called him a "chosen military target." So here I was bringing my father to meet the family and saying, "OK, here he is. Here is 'some Jew.'" I felt like a matchmaker on the world's craziest blind date: "Dad, meet the people who want to see you dead." And it sounds crazy and it was crazy, but so is everything that's going on right now. It's not a solution, but it's a beginning.

In all those long letters to Omar, you presented the idea of the human David Blumenfeld. He returned pages of political ideology. Do you really believe that Omar got your message?

He definitely recognized that I got revenge on him, which made me happy. He said so recently in an interview with ABC. And he said so to me and to my father. He wrote a letter to me and said, "You get me feel so stupide that once I was the cause of your and your kind mother's pain. Sorry and please understand." And then he said to my father, "She [Laura] was the mirror that made me see your face as a human person deserved to be admired and respected."

Did he say he would change?

He told ABC that he was sorry and that he was going to put aside violence. Who knows what lies in his heart? But he stated publicly, at a time when there's tremendous community pressure to close ranks and denounce any kind of overtures to Jews and to defend violence as a means of negotiations: "No, I think that violence is the wrong way and I'm sorry for what I did to you and I wish you well." He addressed my father directly in a recorded message. That says something.

Omar's in prison. He's with people who are justifying their existence by their act -- whether it was planting bombs or shooting tourists. Whatever it was, that's their reason for living and their reason for being in jail. Omar's been in jail now for 15 years. If he can say that what he did was wrong and was a mistake and he's willing to say it publicly, that's something.

You stress in the book that this endeavor was personal and not about national identity. But what did your study of revenge reveal about the Middle East conflict?

I learned a lot about the mechanics of the psychology of revenge. And one important thing that fuels revenge is humiliation. In an Arab society, pride and honor are very important. Palestinians feel humiliated, whether it's an individual Palestinian being stopped at a roadblock or the fact that their entire Third World society lives next to this wealthy, Westernized society. The Palestinians are thinking, "Why are we deprived?" So there's this national humiliation and individual humiliation that definitely fuels the search for revenge on the Palestinian side.

For the Israelis, their state was built on the ashes of the Holocaust, which was for them the ultimate experience of victimhood. There's this revulsion at being a victim. There's a cycle called "predator and prey" where people feel like, in order to avoid becoming a prey, they have to become a predator. In Hebrew, the word for revenge is "nekamah," which is linked to the verb "kum," which means rising. So nekamah is about being a prey and becoming a predator, rising up. Israelis are obsessed with security and not being suckers. So they feel like whenever they're attacked, they have to attack back. Whether or not it benefits them strategically or militarily, it answers the public need to lash back.

So on one side you have humiliated Palestinians who feel like they need to get revenge, and Israelis who can't stand the idea of absorbing a blow without returning a blow. For their own reasons, they feel like they have to strike back.

Then you have these two leaders, Arafat and Sharon, who are playing out this grudge match from 1982 in Beirut in a kind of death clench. They're absolutely trying to rewrite the history of the Lebanon War by reliving it today. Ramallah is on its way to looking like Beirut.

In the end, when you revealed your identity to Omar in court, your mother stood up and said, "If our family forgives Omar, Israel should." And after all your searching for revenge, you opted for forgiveness, too.

No! Forgiveness was never an option. I had too much to prove. I had some points to make and I knew that I wasn't going to make them through forgiveness. One of them was about the nature of evil in the world. Is it possible to transform evil? Everybody's always preaching forgive, forgive, forgive. And sometimes you can't forgive. So let's just be honest about what we're feeling. Sometimes we want to get even. I'm not advocating that you get out a hatchet and whack somebody. In America, revenge is a darkness in ourselves that we deny. I would tell people that I was writing this book and there would be this pinch between their eyebrows, they would take a step backward; the word itself is threatening.

What I was trying to say is, don't deny it, build something with it. The need to get even is universal, but it doesn't have to mean piling one misdeed on another. You can satisfy the urge to get even by educating the person who wronged you and helping to end the cycle of revenge rather than continue, which is what I hope I accomplished with Omar. I got down into the muck of revenge as a reporter, and also as a daughter, and I came back up with a message of hope.

Do you think that revenge is justice?

For some people they're synonyms. Really, I think they exist on a continuum. Most people see them as opposites -- revenge is personal and justice is procedural. Revenge is subjective and justice is objective. But one shades into the next. If you can imagine a rainbow: Justice shades into punishment and that shades into retribution. And you have reprisals and counterstrikes and getting back and getting even and then you're into revenge and then vengeance and vendettas ... and then you're in Sicily.

A lot of times it's just language. Right after Sept. 11, Bush started talking about revenge. Then one of his aides said, "No, it's justice." Even in death penalty cases, the families of the victims will say, "We want justice, not revenge." It's semantic.

I asked the Israeli military chief of staff, "What's the difference between revenge and retaliation?" And one of his generals piped in and said, "It depends. When we do it, it's retaliation. When they do it, it's revenge."

Do you feel better now?

I do. I never knew where I would end up. I was hoping that I didn't end up being self-destructive because in all the revenge stories we read and the morality plays, revenge often ends up with the avenger dead or hurt. So I was trying to find a new ending to the story.

What was it about your revenge that didn't make the Khatibs continue the cycle?

I found redemptive revenge. I performed this impossibly optimistic act that left me vulnerable. On the one hand, they saw what they had done wrong, and on the other hand, they felt sort of grateful toward me. Even though they know that I got revenge on them, they sort of understand why and accept it. I got the acknowledgment that I was looking for -- that my father is a human being and what Omar did was wrong.

Were they surprised when they found out who you were and that you were Jewish?

Completely. Even though it's obvious. Anyone in America or New York would know I was Jewish. You don't get more Jewish looking than me. No, they had wished me merry Christmas and happy Easter. They assumed that because I was a member of the foreign press, I was Christian. And they never imagined that I was the victim's daughter. But they did say that they thought I might be a CIA operative or some kind of government agent.

But you didn't see a flicker of anger when they discovered your identity?

They were so shocked by who I was and what I had done. They were just crying and stunned. The Jewish part was the least of it. I was the daughter of the man that their brother tried to kill.

Shares