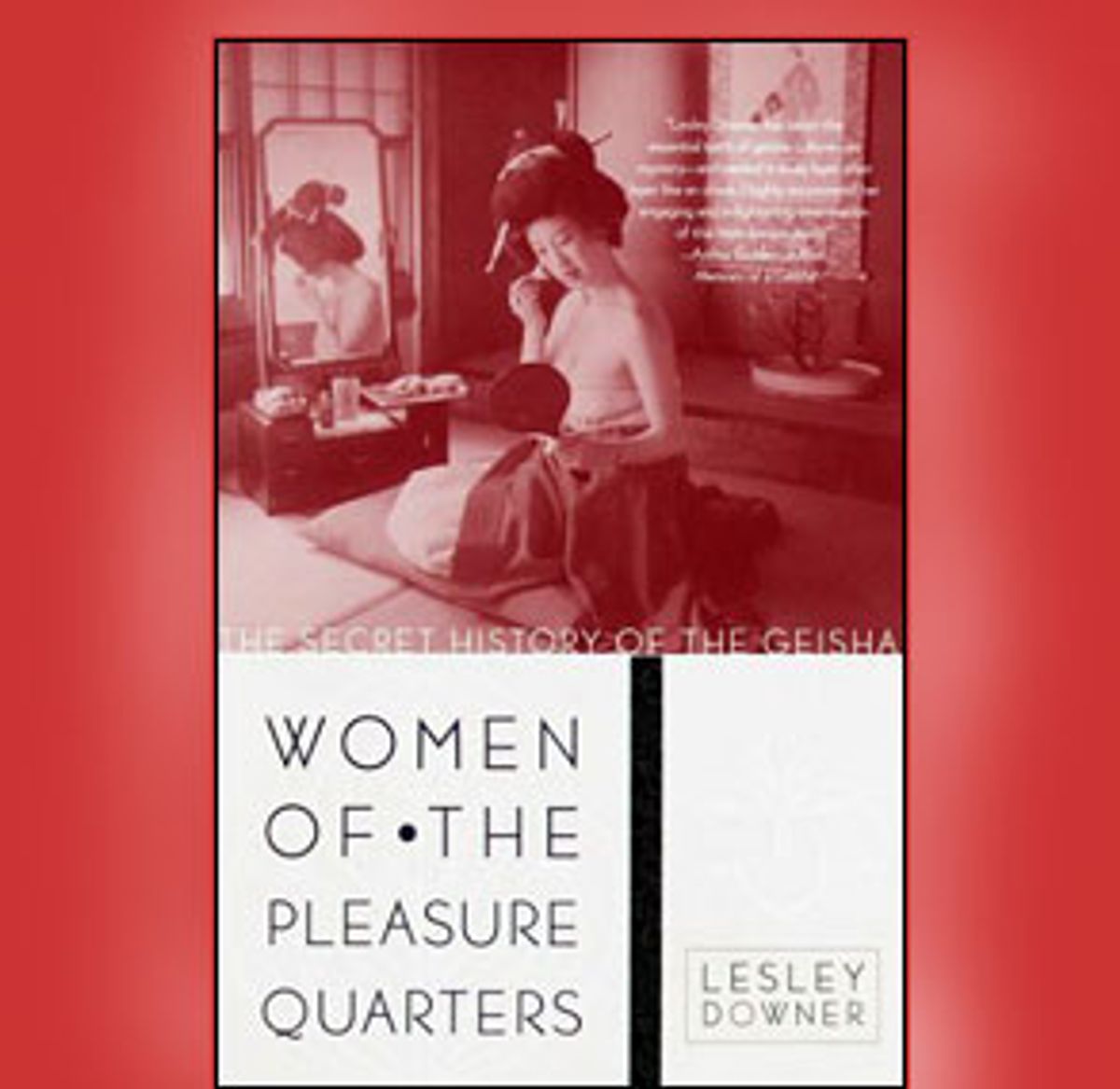

Geisha have been the subject of Westerners' fascination and fertile imaginings for well over a century, but Lesley Downer's "Women of the Pleasure Quarters: The Secret History of the Geisha" is one of the few books to trace the history of these extraordinary women and explore the realities of life behind the flawless geisha mask. In their heyday in the late 19th century, geisha were counterculture queens, confidantes of the greatest men in the land, and their parties were essential to the running of the country.

Times have changed, but despite regular predictions of their imminent demise, geisha are still to be found in towns and cities across Japan. Their world, however, is a secretive one, a closed society where prospective customers must always be introduced by an existing customer of long standing. Thus, despite being one of the most enduring symbols of Japan, geisha remain "not quite respectable," their status precariously balanced somewhere between artist and prostitute. Guardians of a unique and fragile tradition, they have declined in number dramatically over past decades and they face an uncertain future.

Downer, a writer and journalist, lived in Japan for more than a decade and is author of a number of books on the country and its culture. She now divides her time between New York and London, where I spoke to her at her Islington home.

What inspired you to write about geisha?

It began with friends of mine reading "Memoirs of a Geisha" [Arthur Golden's phenomenally popular novel] and asking me, the Japan specialist, "So, is it true? Is it authentic?" I felt, well, I've got to find out! I was very curious -- I thought, here's this very secret world that people don't know about and it would be very interesting to break into it and find out who these women are.

Westerners commonly assume geisha to be linked to prostitution. How much truth is there in that?

I don't think geisha are prostitutes because I don't think that they need to be; they have perfectly good incomes without that. But in the past many of them were prostitutes and today's "onsen geisha" [low-class geisha who work in hot spring resorts] probably still do a bit of that as a side business. So people think, "Well, if onsen geisha do it, then I guess that's what 'geisha' means."

The whole fascination of geisha is that there is this kind of ambivalence of "Do they or don't they?" With almost any other category of people anywhere else in the world you can answer definitely, yes they do, or no they don't. But with geisha there is this question mark. On the other hand, when you meet these grand old geisha ladies, my God, it's like asking if a duchess is a prostitute. No! You wouldn't dare for even one second consider it! But it's that not really knowing that gives geisha their fascination and allure. It makes them not quite respectable -- and that is why the interest goes on.

Something that Westerners don't appreciate is that becoming a geisha involves very serious study. It's like joining the Bolshoi Ballet or studying opera. As far as the geisha are concerned, it is their art that is their job. Westerners think that their job is sitting, giggling, at parties, but actually that's not their job. That's how they make money so that they can go to classes and learn their art. What's interesting for geisha is their music and dance. Therefore they are understandably keen to correct the misapprehension -- which is also prevalent in Japan among people who don't know -- that they are prostitutes.

Geisha are also misunderstood within Japan?

Yes. Lots of "maiko" [apprentice geisha] said that their fathers didn't want them to become geisha because they were worried. But this is the whole point; this is the ambivalence. Most Japanese have never met a geisha. The geisha world is a closed society, and so the average Japanese has no idea what goes on inside a geisha house. One Tokyo geisha said to me, "People" -- and she didn't mean Westerners -- "think that we get up to bad stuff, but we don't."

An extension of this is that Japanese think that it is odd that Westerners are so fascinated by geisha -- the fact that we take as our icon of Japan people who are supposed to be prostitutes. Why should that be the representative of their country?

Geisha charge astronomical rates. Are they very wealthy?

I think they're quite rich, yes. They all go on and on about how difficult it is economically, but there are a lot of new houses [in Kyoto's geisha districts], lovely new houses. They charge a lot of money, but their expenses are high -- buying a kimono costs an awful lot of money. And they have to have a different kimono each month. In fact, they have to have three: one that they are wearing, one that's at the cleaners, another one just in case. So that's 36 kimonos, absolute basic, and each kimono costs $3,000 to $5,000 minimum. That's a lot of money!

So that's why geisha traditionally have a "danna," or patron?

Yes, if you have a danna, then he pays for everything. But if you haven't got a danna, then you have to pay for it all yourself.

Surely there are many fewer danna these days.

There aren't very many at all. The figure I heard is that about a fifth of geisha have one. But it still goes on. People would tell me so-and-so is a great danna -- presidents of companies that we've all heard of, major business figures. In fact, I think it goes on more than they'll let on. Geisha don't tell you that kind of thing.

Do geisha still strive to attract a danna?

I think it depends. Some said that they didn't want one. Having a danna is basically like being married -- there is a man who is in control -- whereas in a way the whole attraction of the geisha life is being like me, a modern Western woman. You can do anything you like, whenever you like. Having a danna means that you have to have sex with him if he wants sex. And if you happen not to love him, which is quite possible, then you might not fancy that. So if you can support yourself without one then maybe it's better. Suppose that I meet a very rich man who wants to marry me, but I happen not to be in love with him. Then I have to make that decision: Do I marry him anyway? And I think I might decide no.

You have to remember that the whole concept of patronage in Japan is a bit different from here. There are people who would give any creative person money -- a bit like [advertising executive and art patron] Charles Saatchi -- and a man can be a danna in that sense. They can decide that they want to be like Henry Higgins; they want to rear a gorgeous young thing but they do not require sex of her, so they are just her patron.

How many geisha are there today?

There is a geisha registry where figures are kept of "town geisha" (most towns have geisha), which are probably what you would call "true geisha." And if you add up all those figures, it comes to about 2,000. In all there are about 5,000 geisha, 2,000 true and 3,000 lower-class onsen geisha. In Kyoto I think the figure is about 180, of whom 50 are maiko. And Tokyo has about the same number.

You speak of the "vanishing world of the geisha," and yet you seem to see hope for the future.

I really don't know; I think they'll be OK for another decade. But the main problem is the customers. Most customers are now very old, and being a customer is also a skill. The geisha arts are like kabuki or opera -- an acquired taste. But more than that, the customers should be able to join in. In the past they would know the songs, they would sing, they would dance. And so the question is whether the baby boomers who are now 50, 55, people who have grown up going to French restaurants and skiing in Switzerland, are going to suddenly change and start going to geisha houses.

They might, because people do. I mean that as people get older their tastes change, and they might decide that that's what they want to do. But geisha numbers are definitely declining, and the old ladies are saying that they think this is the end. It may not disappear completely, but if it does continue, another question is, Will it be the same? The essence is that geisha are exclusive. If the only way that they can survive is by becoming not exclusive -- being turned into a tourist attraction -- then OK, they'll survive, but they won't be like the geisha of old anymore. Their greatest challenge is to stay true to their art. How are they going to survive and yet remain themselves?

You seem to identify quite closely with the geisha.

Until I met the geisha, the lives of women in Japan had always seemed to me to be really different from my own life. As a single woman, I had never fit at all into the normal world of Japanese womanhood -- marriage and children -- whereas when I met the geisha I felt that I fit in absolutely perfectly! We all get up very late; I know lots of men and so do they; they don't do any cleaning and they also can't cook. So all the things that Japanese women always do, geisha do not do. They are like the two sides of a coin.

So the geisha lifestyle really is totally different?

Absolutely. In Japan, even rich married women still do their own cooking and their own cleaning. It just is not done to have someone to clean. So geisha have this incredibly different lifestyle. For example, there was the time when I went to have coffee with a geisha and we just sat there talking. I kept thinking, Where's the coffee? Put the kettle on! But she just sat there and kept talking. And then the doorbell rang and it was a man with two coffees on a tray, and I thought, Wow! Talk about not cooking. That's the ultimate 'not cooking'!

Did the geisha feel that you fit in among them?

I felt that I fit in nicely, but I don't think they thought that, because geisha think that they are unique. They couldn't possibly think that anyone would fit in. And I began to realize that the reason they were so bloody rude to me, which they were at times, was because I didn't fit into their categories: I wasn't a man, therefore I wasn't a customer. And if I was a female then I ought to fit in, but I didn't because I didn't know how to behave properly. Most Japanese very politely let you get away with awful mistakes, but the geisha never did; they told me off the whole time. All these old ladies kept barking at me whenever I got things wrong. It was also good as "geisha training" in that I had to learn to be incredibly humble and polite. Whenever they were rude to me and snapped at me, I had to reply, "Thank you very much for teaching me so much."

How would you now answer your friends' questions about the authenticity of "Memoirs of a Geisha"?

I think that people tend to forget that "Memoirs of a Geisha" is fiction. It's fantastic fiction, a brilliant novel, but it is a Western novel, written by a Western man for Western readers. And it seems to me very obvious that the structure of "Memoirs of a Geisha" is the Cinderella story: You've got the ugly sisters; you've got the wicked stepmother; you've got Prince Charming. Whereas there is a fantastic book by Nagai Kafu called "Geisha in Rivalry," which is a kind of Japanese "Memoirs of a Geisha." And I like it better -- it's darker.

I think "Memoirs of a Geisha" is a bit pretty, whereas "Geisha in Rivalry" feels much more authentic and gives much more the geisha view of life. It's about this gorgeous young geisha who falls head over heels in love with a kabuki actor. But the whole point is that for a geisha to fall in love is a disaster, a complete disaster! He then goes off with another woman and the geisha heroine is completely heartbroken. But then the old lady who runs the geisha house where she lives dies, and she inherits the business. So the "happily ever after" in geisha terms is not meeting Mr. Right, it's obtaining financial security, and that is much more authentic, I think.

Does the geisha world still hold enchantment for you?

Oh yes, more so! The more I know about them, the more I can see the point of it. It seems to me to be a very appealing lifestyle in many ways. They are very impressive women!

Shares