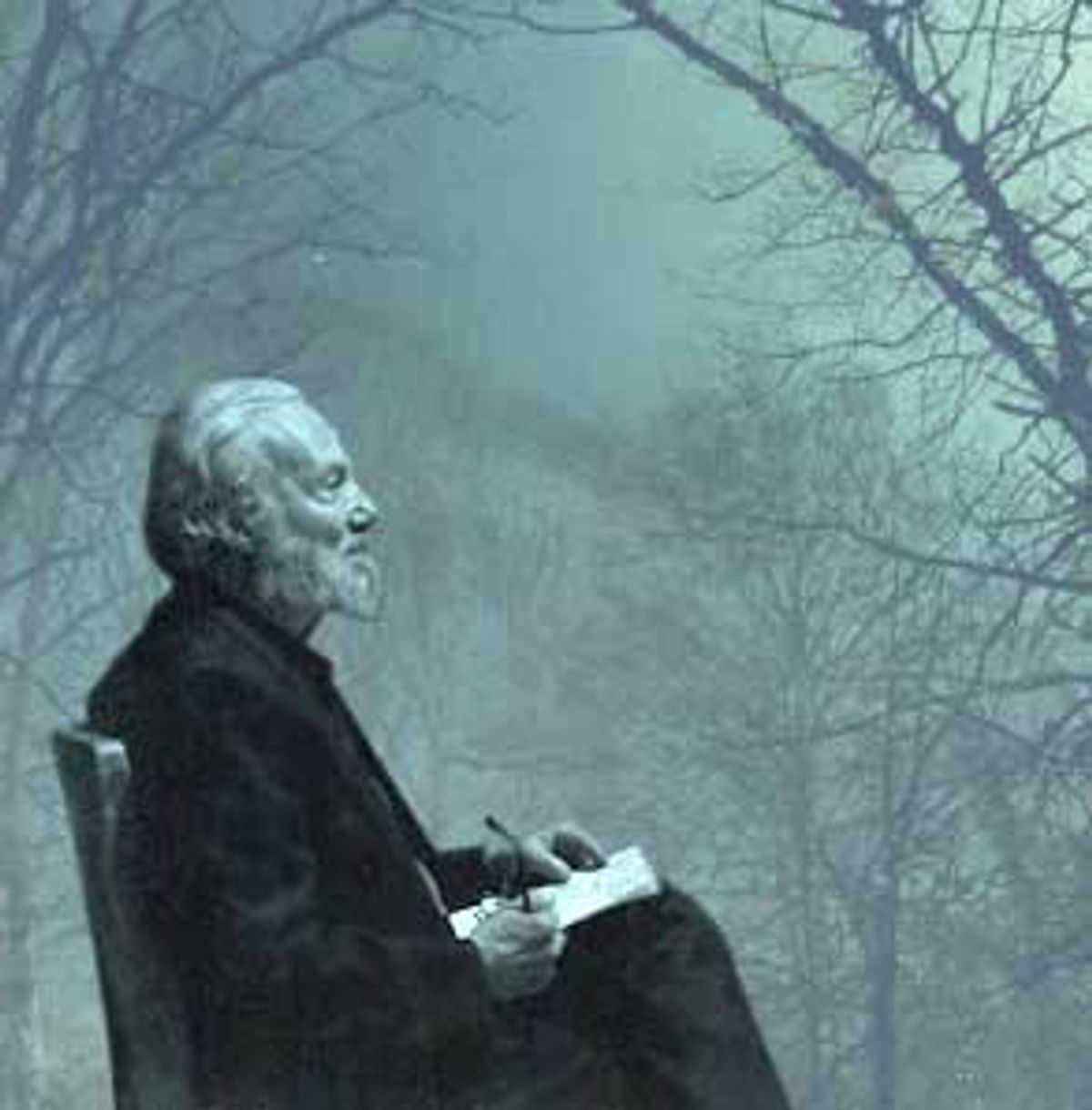

Once upon a time, literary critics mattered -- if the most renowned among them were not quite household names, they were close to it. Those days are gone, but one of the last of the giants lives on in both real life and reputation. You might have caught Meadow Soprano explaining Leslie Fiedler's famous theory about the homoerotic subtext of Herman Melville's "Billy Budd" to her mother Carmella on a certain hit HBO series recently, but you can also read Fiedler's brand-new introductions for Modern Library editions of novels by James Fenimore Cooper and a forthcoming introduction to writings by Jack London. At 85 and in frail health, Fiedler, the author of the landmark work "Love and Death in the American Novel" (1960), has never stopped writing.

Over a period of 40 years, Fiedler met and wrote about most of the major American writers of the 20th century. During the same period, he produced more than 20 books -- including his crossover success "Freaks" (1977), a survey of the figure of the misshapen person as it has appeared linguistically, psychically and sexually in human culture from the earliest cave paintings through film and comic books -- and pursued a career in academia, first in Montana and then as the Samuel Clemens Professor at the University of Buffalo.

Fiedler did not just write about America's literature; he also helped to shape it. The novelist John Barth wrote that Fiedler "is a mentor from whom this incidental, often skeptical, sometimes reluctant mentee never failed to learn." His biographer, Mark Roydon Winchell, writes, "In my judgment, Leslie Fiedler is the single most influential critic of American literature ever." Even the singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen, in a poem written for a book dedicated to works about Fiedler, paid tribute to the critic's legacy, describing how so many readers have learned to imagine him: "leaning over the American moonlight / like the shyest gargoyle / who will not become angry or old."

Fiedler's critical style was as important as his ideas. In his essay "Hemingway in Ketchum," Fiedler regales us with an account of his visit with Hemingway in Idaho, and examines Hemingway's career and persona, never hiding or repressing his own presence. Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, writing in the New York Times, caught the essence of the Fiedler style: "What is remarkable about Fiedler's career is the way his use of the [pronoun] 'I' serves to expand the reader's vista to a rich intellectual landscape instead of reducing it to the narrow confines of the ego."

Salon spoke with Fiedler in his home in Buffalo, N.Y., where he talked about his encounters with Hemingway, Faulkner, W.H. Auden, Saul Bellow and Martin Luther King Jr., and shared his thoughts about whose writings will stand the test of time.

In your essay on Hemingway, you write that the first thing he asked you was "Do you still believe that stuff?" -- meaning the homoerotic nature of the relationship between Huck and Jim in "Huckleberry Finn," which was the subject of your famous essay "Come Back to the Raft Ag'in, Huck Honey." About "Moby-Dick," you wrote, "the redemptive love of man and man is represented by the tie which binds Ishmael and Queequeg," while Ahab's heterosexual relationship stands for "commitment to death." Do you still put this forth as a major strain in American literature?

Oh yeah, it seems to me the thing I've really hung on to, which I've seen in the world ever since. It's as true as anything is. It's simple -- almost abstract. Actually Cooper was the one who started it all with Chingachgook and Natty Bumppo, but I don't know where Cooper got it from.

And you see it from Cooper, to Melville, Twain, Hemingway, Capote?

[Nods emphatically] That meeting with Hemingway unnerved me completely. I wasn't thinking about what he said in terms of whether I still believed my theories on Huck and Jim. Somehow he was playing the wrong role.

In that whole essay he seems to be playing the wrong role. He comes across as almost frail when you met him.

Yeah, I agree. Gertrude Stein really thought of [Hemingway] as frail. He almost married Stein. I once met Glenway Westcott, who told me two things about Hemingway. That he really almost married Stein, but Alice B. Toklas finally grasped her away. And two, that he had a love affair with his sister. Westcott told me that.

Hemingway with his own sister?

Yeah.

If that's true it would mean rethinking the relationship between Jake and Lady Brett.

It would, wouldn't it? It's such a funny relationship anyhow. Lady Brett is the real macho character.

When my students talk to me about Hemingway being misogynistic, I say in his life, yes, and he had huge flaws, but read "Sun." It has one of the strongest female characters in American literature in Brett Ashley.

She's macho, not lovable.

But she's independent, having affairs with no authorial morality put on her.

None of [the male characters] really measures up. Cohn is at the bottom of the heap. But even the toreador, he's just putting on his elegant clothes.

You've described "The Sun Also Rises" as the death of the Jamesian and the birth of a new --

But it's funny. One novel. Even Hemingway couldn't do it again.

I was curious what you thought about all these lists of great novels from the last century that came out in the last few years. Usually Joyce was No. 1. "The Great Gatsby" is No. 2. Hemingway is way down the list, which is fascinating, because his influence had been so great for 50 years.

Yeah, it's fascinating. Here are three guys who wrote at approximately the same time -- Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Hemingway -- and they've done very well. "The Great Gatsby" is absolutely unique in American literature; it's the only neatly organized book written by an American. "The Scarlet Letter" comes close. Fitzgerald never did it again. The only thing of his that stays in my head like that is the short story "A Diamond as Big as the Ritz," which has a special appeal for an old Montanan.

Hemingway seems to be in a funny position. People nowadays can't identify with him closely as a member of their own generation and he isn't yet historical.

You described Norman Mailer's "An American Dream" as being "more like pop art than the dying novel." Do you think the novel evolved into pop art and do you think that the novel is still dying?

The novel is always pop art and the novel is always dying. That's the only way it stays alive. It does really die. I've been thinking about that a lot.

I've been writing about James Fenimore Cooper. He was not a writer. Here was a man who was 30 years old and had never put anything more than his signature on paper and his wife annoyed him by reading Austen or maybe one of her imitators to him. He said, why are you wasting your time with that? Anybody could write a better one. I could. His wife said, I'd like to see you try.

He sat down and wrote a novel which is absolutely indistinguishable from Austen, completely from a female point of view, completely English, no sense that he was an American, the language is British English. Her novel was called "Persuasion," his was one word like that. It was a terrible flop because he discovered that if people wanted to get a novel written by an English woman, they'd go to England and get one. And the new fashion he discovered was this strange Scotsman who couldn't make it writing poetry and decided to write novels, so he [Cooper] turned around completely. And one kind of novel died and another began.

Jane Austen is at the end of the line that begins with [Samuel] Richardson, which takes wonder and magic out of the novel, treats not the past but the present and so forth and suddenly [the novel] switched back again to the sort of thing that was written about in the romances. The other thing I've been saying for a long time, and I'll keep on saying, is that the novel doesn't come into existence until certain methods of reproducing fiction come along. The novel is the first art form that is an honest-to-god commodity. I guess that's what I mean by "pop." That's what makes it different from both high art and folk art.

You wrote that "The tone is established once and for all in the work of Nathanael West, in whom begins ... the great take-over by Jewish American writers of the American imagination, ... of the task of dreaming aloud the dreams of the whole American people." Is the Jewish imagination still dominant or what has taken its place?

It's gone. It went pretty quickly. I say the name of Saul Bellow to my students and get a blank response. They don't even know of him to say bad things about him. The postmodernists were almost all goyim.

Which "goyim" novelists have taken over that imagination?

Well, they're gone now, too. The ones that interested me when they came along were Hawkes, Barth.

How about Pynchon?

I've had a tough time with Pynchon. I liked him very much when I first read him. I liked him less with each book. He got denser and more complex in a way that didn't really pay off. You had to work twice as hard for half as many returns.

How about Don DeLillo?

I don't really like his writing much. He does many different things. In some ways, he never seems committed to me to what he is writing. Very nice surfaces, but he's got nothing underneath. I keep feeling I'm unfair to him. I talk to many people, and he's one of the few contemporary novelists who still has enthusiastic followers.

Anyone else who you like?

The one more recent novelist to come along, and he is not that recent but he's been discovered more recently, is Cormac McCarthy. Him, I like. I have a prejudice in favor of anybody who takes off from where Faulkner stops, except possibly for the lady who got the Nobel Prize. I deliberately repress her name.

Toni Morrison.

Yeah. That's the other group that moved in, the female black authors. I really like Morrison's early books a lot. But she's really become so much a clone of Faulkner. He did it better.

The other thing I love is the really popular novel. Stephen King really fascinates me. Because he's a secret intellectual, lurking behind. While he was writing all those books that made so much money he was going around doing lectures for 25 or 30 bucks -- and you'll never guess on what. On William Carlos Williams and "Patterson"!

That's wild, because he has confessed to not reading so much.

I once appeared on the same platform with him. And he was extremely polite and he called me "professor" and then we went to the plane -- and he went to first class and I went to tourist.

I really got in trouble with the postmoderns because of him. They were talking about how they were the leading edge of literature. And I said, "You're way out there, you rebels, you Ph.D. professors with your six-figure salaries." I was feeling a little wicked and, as Auden would say, "naughty," and said, "Look, let's be frank with each other: When all of us are forgotten, people will still be remembering Stephen King." I didn't say you; I said "we." And the reaction was hostile beyond belief, and they wouldn't let us sit at the head table for the formal dinner that night and [my wife] and I were shoved off to the children's table.

What do you think of William Gass?

Aside from that one story, "In the Heart of the Heart of the Country" -- I love that, it's great, he just did it once -- let's be frank, he's a bore. I know him very well.

Does he know you think his novels are a bore?

Writers always know whether you like them or not. The reason Saul Bellow doesn't talk to me anymore is because he knows his new novels are not worth reading. He and I were really close friends. We had a friend in common, a guy called Seymour Betsky, who spent most of his life teaching in Holland. Once Saul was in Holland with Seymour in the Rijksmuseum, and he said, "Leslie's in town. Do you want to get together and sit around and talk like the old days?" At the top of his voice, in the midst of a crowd of tourists, a large crowd, Bellow yelled, "Leslie Fiedler is the worst fucking thing that ever happened to American literature!" [Laughs uproariously] Back in the bad old good days, in 1939 and '40, I'd hitchhike to Chicago from Wisconsin. We were piss-poor, and I got in with a group of people, all of whom were writing their first novel, all dreaming they'd get the Nobel Prize, and goddammit, one of us did get the prize.

Another writer who I was curious about is Henry Miller and his place in American literature.

I still have students who respond to Miller, but not to Hemingway, who doesn't really interest them.

I think Miller has had huge influence not because he wrote about sex, but because the memoir or the nonfiction novel has become such a monumental force in American publishing, if not in literature. Miller wrote novels, but he calls his protagonist Henry, often Henry Miller, and his books are in this gray area between memoir and novel.

The American novel is always so personal -- even when it's not memoir, it's as if it were memoir. I mean, Huck Finn. That's why it's so wrong when I pick up a new edition of "Huckleberry Finn" and I look at the last page and it doesn't say "yours truly" at the end.

A Leslie Fiedler essay is so imbued with your personality and persona. I think you reinvented the American essay with the critic an integral part of that criticism. As part of the art.

I do in fact believe that all good criticism should be judged the way art is. You shouldn't read it the way you read history or science. Finally, I think [what] I like best is that people who are not experts can not only understand but get engaged by my work. I like that Joe Paterno can read me. That Bill Bradley calls me up and says, "I've been reading an essay of yours."

I was doing some reading about your split from the Partisan Review, and I found this quote: "The clash of highbrow versus lowbrow has gradually usurped the place of class war in its working mythology."

There are things in American culture that want to wipe the class distinction. Blue jeans. Ready-made clothes. Coca-Cola. We were talking about Henry Miller: Is it high art or is it -- if it imitates the popular form, say a detective story or science fiction -- what is it? Then there's the middlebrow, which I hate. Then there's what escapes those [categories] completely. I think Mark Twain is like that.

You called John Cheever middlebrow and the New Yorker a middlebrow publication a couple of times throughout your essays. You still stick by that?

Yeah. One could call Twain middlebrow -- but he isn't. He is both high and low at the same time. True highbrow will hold true. When I was 12 years old, someone took me to see Martha Graham. It was nothing like what I thought of as serious dancing and even then I knew I was having a great experience. It was as if somebody was moving through space like no one ever did before.

And the greatest artists are like that. Shakespeare -- no one was stupid enough not to get something out of his plays. A few people were too smart to get anything out of his plays. He'd make these vile puns and the higbrows say "he's not spelling 'cunt'" -- the hell he's not! Sophocles was like that. He won first prize every time it was put on and it was audience vote.

There are the Sophocles and Shakespeares and then there are the Kafkas.

Kafka is still unrecognized. He thought he was a comic writer. Dickens and Kafka had one great advantage that removed them from the highbrow/lowbrow thing: They were crazy out of their minds. I don't know which one was crazier. Faulkner had that quality too. He writes these tough, tough books, but he had the voice of the guy sitting there at bar. I like to start people off reading "Sanctuary" and move them to "Absalom, Absalom."

Joyce is another person who is close to popular literature. It's funny how interest in Joyce has brought together so many people who are so different: Umberto Eco, Helene Cixous, Marshall McLuhan.

Joyce seems to be your great umbrella that covers all other writers.

I think the pattern of my essays is "A funny thing happened to me on my way through 'Finnegans Wake.'"

Did you ever meet Faulkner?

Yes, indeed! One year, when I was chairman of the English Department in Montana, I said, let's give the boys a thrill. I set up a program of readings: Auden, Faulkner and Dylan Thomas. Thomas didn't make it. He hit the booze a little too early and ended up in Seattle. My only conversation with him consisted of his saying over and over again, "Things are frightfully mucked up."

Auden was a great man. Auden behaved exactly as I wanted him to. We took him out for dinner at a Montana steakhouse, totally macho, full of guys who looked like they would beat any queer they caught coming down the street, and he was feeling "naughty," and two girls come through the door wearing homemade gowns from the prom and he said at the top of his voice, "My dears, I know exactly how they feel -- I used to be a mad queen myself."

Faulkner turned out to be great. At the public occasion, he was terrible. He was very small, really tiny, and we had built up a place for him to stand so his head would come up to the mike, but he kept tossing his head back and talking lower and lower. But when he talked to the classes afterward, he turned out to be a great teacher. When a student asked a question ineptly, he answered the question with what the student had really wanted to know. Then he sat in our living room and read from "Light in August" and that was incredible.

I had gotten instructions from his editors about how much he should drink before lunch and before dinner and special instructions -- don't put him next to any inquisitive woman who will want to talk literature. So he ended up next to a woman who asked why can't Montana writers write about Montana [the way you do about Mississippi], and he said, "To write about a place you have to hate it, like you hate your own wife."

You know what it cost me to bring those people there? Two hundred dollars apiece to bring them there, and I didn't have it, so I went around to the local churches and they put up the money. Auden gave us a present when he left -- a book nobody had heard of in America yet: "The Lord of the Rings" trilogy. And I gave him the American equivalent, "The Wizard of Oz."

When did you give up writing book reviews?

I can't remember. At one point I gave up writing blurbs because you make one friend and 200 enemies. But I liked doing the reviews. I wrote the first reviews of Bellow's books and when I stopped doing reviews, he decided "[Fiedler] isn't reviewing 'cause he doesn't like 'em." He never took my advice when he was my friend.

Did Mailer ever get on you for anything you said about him?

The last time I saw him he was very friendly. We had a sort of physical competition. I used to be fond of Indian arm wrestling and I beat him and he didn't like it. I introduced him to Saul Bellow. They'd never met each other.

Out of that whole group of writers, who do you think will last? Is it too soon to tell?

The one who is clearly going to last is Ralph Ellison. Mailer, I'm not sure about. Bellow will last. I don't know how high he'll be in the pantheon. I used to think Barth and Hawkes had a chance. I'm not so sure now. Barth's most recent book was terrible. And he sorta knows it too, I had a note from him which mentioned the reviews.

What do you think of Grace Paley? I love her stories.

Oh, she's very good. Grace is not in the front of anyone's consciousness, but when you talk she makes everyone's list.

Raymond Carver?

Oh, he's good. I think he'll be appreciated more and more. He's an easy writer to imitate.

What do you think about the present university situation in the U.S.? Of the rise of the MFA program?

I don't much like what's happening. This department has gone the way -- not that all colleges have gone, but they talk not any human language. They talk Derrida-style, Lacan or Foucault. Foucault was the one person I met [in France] that I could talk to. He was a mensch. He talks to you, you know whether you agree with him or not because you know what he is saying. He was a great influence on my "Freaks" book, his book on madness.

In that book, you make the point that most "freaks" live the same unhappy or happy lives as the rest of us.

One of the problems I had was the problem of language. Saying "freaks" used to be impossible; this is one of the books that changed that. I love it now that a large minority of people who are "handicapped" prefer to call themselves "crippled." This is all part of the game, [like] queer theory. It's the same game I play with the word "nigger." I've been playing it for a long time.

What is the reaction that you want?

The black situation has changed. They finally realized they're Americans. One of the first times I ever spoke to black Americans, a young kid who was a member of SNCC said Martin Luther King Jr. was an Uncle Tom, and I agreed with him. As far as I'm concerned King was one of the worst human beings I ever met. He would upstage you when you were talking, literally upstage you, shove a hip into you, shove around so he could look at the girls in the first row or so and see which he was going to fuck. I gave him a hard time.

Are you OK with saying this on tape?

Yeah. Absolutely. And when I walked out, I got one of the greatest compliments I ever got in my life: The young kid from SNCC said, "You're a mean motherfucker."

What about Baldwin? You said you wanted to write about him, but never did.

Baldwin, we got to be friends. I like what he did when he started. I like the early fiction and essays. One of the things he wrote frankly about, which I wanted to write about -- I never got around to it -- are the blacks that I think of as "black Jews," whose first work was published by Partisan Review, Commentary, that's just not Jimmy Baldwin, but Ellison.

Among today's critics, whose work do you think is closest to your own?

The person I liked when she began was Camille Paglia. And I liked her even better when I heard her talk. When I celebrated my 80th birthday, they asked me who I wanted to hear talk, and I invited Allen Ginsberg, Camille Paglia and Ishmael Reed. So it was a nice, varied group. I love Allen. He was a great man. We saw each other many times. I knew his father back in Newark. One time when I was doing something at Yale, I saw him out of the corner of my eye with a group of students chanting "Om, Om, Om." As I passed by he went, "Om, Shal-om."

What do you think of him as a poet?

I admire him as a poet, despite the fact that he seems not to know when he is being good and when he is bad. But he will last, or at least those poems will last, the ones in which he finds his real voice. Anybody in the next centuries wanting to know what it was like to be a poet in the middle of the 20th century should read "Kaddish."

What do you think of Paglia now?

I have very complicated feelings about Paglia. In some ways I was delighted when she came here to help celebrate my 80th birthday. What pleased me was to discover that she had a real sense of humor, which enables her sometimes to see what is really funny not only about other people but about herself as well. If I am in any sense disappointed, it is because her most interesting work seems to have been done early and she has got to a point much too soon to start repeating herself.

Do you have any advice for the critics of the future?

It's funny to be a critic, I never met anybody in my life who says, when you say what do you want to be when you grow up, "I want to be a critic." People say I wanna be a fireman, poet, novelist.

Critics? How do they happen? I know how it happened to me. I would send a poem or story to a magazine and they would say this doesn't suit our needs precisely but on the other hand you sound interesting. Would you be interested in doing a review? And then I'd do it and decide that it's easy and you figure you might as well keep your name in front of people and you figure some day they'll run a story. And after a while they did publish some stories, but it's strange ... When somebody asks me what I do, I don't think I'd say "critic." I say "writer."

Do you think someone will go on and finish your work?

I have two answers to that: I hope so ... and I hope not. If there's one thing I can't stand, it's somebody doing something because I pushed them in that direction. What I really dream of is that somebody would blow everything I've done out of the water in a beautiful way which would clear the way for something better to come along. My assignment is what every writer's assignment is: tell the truth of his own time.

Shares