Since Sept. 11, hawks in the Bush administration have presented themselves as evangelists for democracy. The absence of democracy, in the neoconservative analysis, creates the climate of desperation and frustration that breeds extremism. Democracy's introduction into the Middle East, via regime change in Iraq, would bring a bracing new spirit of liberty to the region, undermining the stagnant authoritarianism of Iraq's neighbors.

Yet were it implanted tomorrow, democracy in most of the Middle East would bring to power the very totalitarian theocrats who most menace us. Indeed, argues Fareed Zakaria in his incisive new book "The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad," democracy isn't necessarily the opposite of tyranny. From Venezuela to Kazakhstan, the last decade has seen a rise in elected autocrats, challenging American bromides that posit universal suffrage as the answer for all the world's ills.

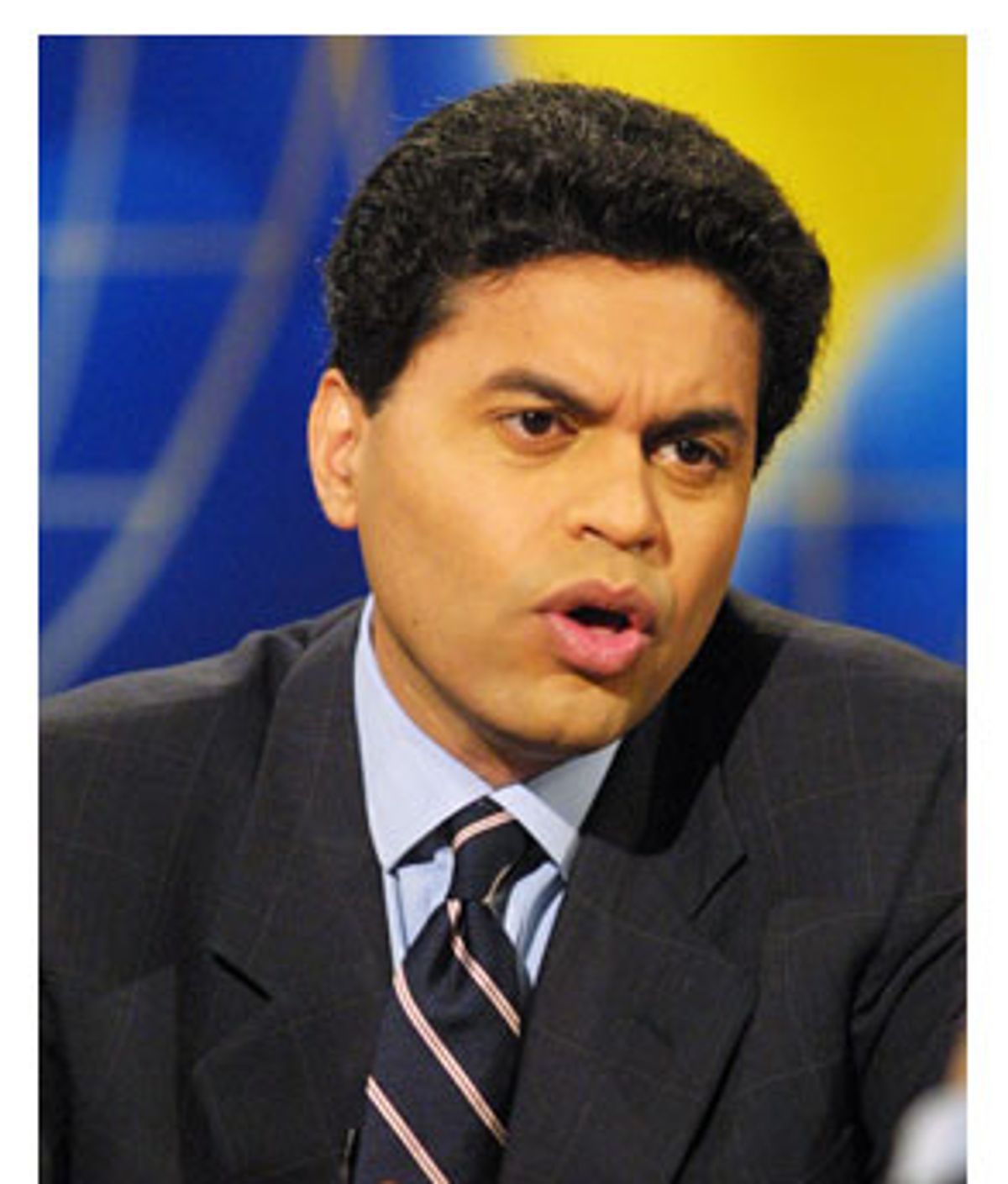

The book and its 39-year-old author, the editor of Newsweek International, is getting an extraordinary amount of attention. In New York magazine, Marion Maneker gives him the movie star treatment, writing, "Dimple-chinned, with expressive eyebrows and a thick head of black hair, Fareed Zakaria could easily be the Indian reincarnation of Cary Grant." He may be the first of a new, post Sept. 11 breed -- the policy wonk as sex symbol.

For all the buzz he's generating, Zakaria's ideas about democracy's failures aren't that new -- in much of the foreign-policy establishment, they've become a kind of conventional wisdom, popularized by writers like Robert Kaplan and Amy Chua. It's clear to anyone who's been paying attention, after all, that the heartening triumph of democracy around the world in the last decade has coincided with brutal outbreaks of ethnic nationalism, civil war and genocide.

Yet Zakaria's book goes further than others, scanning the history of Western culture and identifying a series of fallacious assumptions about the roots of liberty that threaten not just fledgling Third World republics, but America as well: "Western democracy remains the model for the rest of the world, but is it possible that like a supernova, at the moment of its blinding glory in distant universes, Western democracy is hollowing out at the core?"

Freedom, Zakaria argues, comes not from politicians' slavish obeisance to the whims of The People, divined hourly by pollsters. It comes from an intricate architecture of liberty that includes an independent judiciary, constitutional guarantees of minority rights, a free press, autonomous universities and strong civic institutions.

In America, all of these institutions have been under consistent attack for the last 40 years from populists of the left and right seeking to strip power from loathed elites and return it to the masses. "The deregulation of democracy has ... gone too far," Zakaria writes.

Much of what Zakaria writes will anger liberals. He criticizes 1970s reforms that opened up the closed workings of Congress to the public, arguing, "The purpose of these changes was to make Congress more open and responsive. And so it has become -- to money, lobbyists, and special interests." The World Trade Organization is opposed by anti-globalization activists in part because of its secretive, unresponsive nature, but Zakaria argues that's precisely why it works.

"If trade negotiations allowed for constant democratic input, they would be riddled with exceptions, caveats, and shields for politically powerful groups," he writes. The current system, he says, has produced "extraordinary results ... The world has made more progress in the last fifty years than in the previous five hundred. Do we really want to destroy the system that made this happen by making it function like the California legislature?"

To this, many progressives would likely answer yes. Yet they'd be wise not to disregard Zakaria's argument, since it also does much to illuminate the social trends that most trouble them. After all, vitriolic attacks on intellectuals and artists for being "out of step with the American people" are a symptom of the populism run amok that Zakaria is criticizing. When the right attacks Supreme Court rulings that prevent state legislatures from banning abortion, it does so in the name of democracy. Fox News gets its bombast from the notion that The People, in all their provincial, jingoistic glory, are intrinsically wiser than the aloof elites at CNN.

Zakaria's book is in part a defense of elites, of expertise and leadership over poll-driven pandering. It's a rejection of John Dewey's claim that, "The cure for the ailments of democracy is more democracy."

This certainly doesn't mean he argues for authoritarianism. On the contrary, "The Future of Freedom" is an eloquent defense of constitutional liberalism, of the institutions that sustain unpopular liberties. Zakaria is a democracy advocate, but he asks readers to take a more expansive view and see that elections are just one element of a free society. His book, measured and centrist as it is, is a brief against tyranny, including the tyranny of the majority.

It's also a book with immense relevance for the immediate future of the Middle East, since in the short term, the West will have to choose whether to hold elections Iraq and possibly let the ayatollahs dominate, or to impose liberalism, possibly against the will of the people. Westerners rebuilding Iraq will have to realize that, despite America's rhetoric, giving all citizens a vote isn't the same as giving them freedom.

How autocratic should America be in imposing constitutional liberalism in Iraq?

I don't think the United States needs to be autocratic. It has to provide order. If you think about it, the best recipe I can imagine is James Madison's recipe for our own government. When thinking about the American Constitution he said very famously in "Federalist No. 51" that when constructing a government, you have to do two things. First, the government has to control the governed, and then it has to control itself.

In Iraq, what the United States has to do is create order and then begin building the institutions of liberty -- constitutions, courts, power sharing -- before it gets to the hurly-burly of political contests in elections. It's not that you have to be autocratic, you just have to get the sequence right.

But in the short term, America needs to work with Iraqis, and those most committed to building the institutions of liberty might be exiles who would have to be foisted on an unwilling public.

We should do what we seem to be beginning to do, which is to create a broad-based and therefore legitimate group of Iraqis who would begin the discussions about what kind of political system they want. In the meanwhile, while those discussions are going on, authority will largely have to be wielded by the coalition. You're right in that sense -- one can call it autocratic. It's simply common sense that you cannot devolve power to the factions that are at the very moment deciding what kind of political system to put in place.

One lesson of the Balkans was that if you begin the power contest before you build the institutions, everything goes awry because people who are voted into office suddenly lose interest in the rule of law, clean administration and limitations on governmental authority. It's much easier to construct a fair system when you don't know whether you're going to be the ruler or the ruled, because you will have an incentive to create a fair and balanced system.

During that period, the United States will have to wield authority in conjunction with others and with as much international legitimacy as it can muster. That is why the United States should be internationalizing this process as much as possible.

But aren't there dangers in the United States wielding authority for too long? There have already been protests about the town meetings the United States has been holding to identify Iraqi leaders it can work with. People are protesting a sustained American presence in Iraq.

With regard to these protests, you have to weather some of this. Remember, there were a few hundred people protesting. This is what democracy is all about. We have no idea how representative they were. When you invite 100 or 200 people to a national conference, you are not inviting 100 or 200, and the easiest charge for the excluded is going to be U.S. imperialism. My solution to this is that you don't therefore go away, you therefore internationalize the process more.

A multilateral body has been running Bosnia for six years. The U.N. has been running Kosovo for almost as long. Nobody is calling that colonialism. They call it international assistance.

But is there any hope of the Bush administration agreeing to internationalize the process? So far, it's shut the U.N. out.

I think there's no chance in the short term because the administration is set on its course, but things have a way of changing. We were not going to provide security 50 miles outside Kabul, and then it became clear that that position was untenable, that Hamid Karzai's government in Afghanistan was vulnerable to collapse if we didn't provide security, so we changed course. Who knows what things will look like two or three months from now.

What should the role of Iraq's Islamists be in shaping the new Iraqi government?

They should have a role, they should be included, but I think we should be pushing very strongly for the idea that the system of government that is put in place is one that has all kinds of rights and protections, for example for women, so that even if they were to come to power, the Islamists would not be able to adopt a reactionary attitude towards women. It would be impossible to modernize Iraq if you were to not put in place some of the basic protections of human rights and separation of powers. Let [the Islamists] come in for sure, but vigorously use all the influence we have to ensure that they are not able to create an Islamic state. I don't think they would be able to do so anyway -- most Iraqis are quite secular.

You accepted the idea of spurring democratization in the Middle East as one of the justifications for war with Iraq. In your book, you write, "The Middle East needs one ... homegrown success story," and you say that Iraq is a candidate for this role. Yet you also lay out certain criteria for successful democratization, and in writing about Indonesia, you say, "Indonesia in 1998 was not an ideal candidate for democracy. Of all the East Asian countries it is most reliant on natural resources" -- which you say inhibits other kinds of development -- "Strike one. It was also bereft of legitimate political institutions ... Strike Two. Finally, it attempted democratization at a low level of per capita income, approximately $2,650 in 1998. Strike three. The results have been abysmal."

Yet Iraq also has these three strikes against it -- and its per capita income is even lower than Indonesia's was. Why go to war to bring democracy to Iraq if that goal isn't feasible?

It's difficult. My view on building democracy is not that we should not do it in countries that don't meet the criteria. The reason I point to these criteria is just to emphasize how difficult it is to do. When you get an opportunity to try, absolutely you should take it, but you should learn something from those criteria and from history and ask yourself what should we do to try to minimize the danger of democratic dysfunction and maximize the chances for success.

I recognize, living under a terrible dictatorship, you don't get to choose your moment of freedom. The point, however, is to learn from history and to make the most of your moment for freedom.

You point out that in many developing countries, contrary to Western assumptions, elections wouldn't lead to more freedom. In Pakistan, as you write, General Pervez Musharraf has been able to pursue liberalization "precisely because he did not have to run for office and cater to the interests of feudal bosses, Islamic militants, and regional chieftains ... In Pakistan no elected politician would have acted as boldly, decisively, and effectively as he did."

This suggests that those most concerned about social justice should stop calling for open elections in all countries. What, then, should they be calling for?

They should be pushing for human rights. More than anything else, the ability to protect individual rights is going to lay the groundwork for liberal democracy. How do you protect them? Most effectively through a court system, through laws that guarantee human rights. The other stealth method of political reform is economic reform. Economic reform has the effect over time of producing political reform because it creates the need for the rule of law, a cleaner and more responsive administration, and most importantly a middle class that presses the government for a greater political voice.

In Pakistan, for example, it would help not at all to press Musharraf to hold more elections. The last ones were almost won by Islamic fundamentalists and they have no interest in reform. The best course there is to press Musharraf to engage in the kind of broad structural reform, of the legal, economic and political system that will then be the basis for a genuine democracy.

Does this require a paradigm shift for liberal human rights activists? In the recent past, progressives have condemned efforts by the West to impose our values on others. It's one thing to say people should choose their own leaders, and another to say our governing values and institutions are superior.

It requires a paradigm shift for modern liberalism and the recovery of the older, more muscular liberal internationalism that's pre-Vietnam, pre-postmodern. I don't think Dean Acheson or Harry Truman or Franklin Roosevelt would have had any trouble with the idea that constitutionalism and liberalism were better forms of government than dictatorships or theocracy. This is all part of the recovery of self-confidence that liberalism needs to undergo.

I think many liberals would ask how they can trust this government to export liberty abroad when it seems to undermine liberty at home.

Again, this is part of the problem of liberalism today. The United States has problems, no question, but they are in no way and on no scale comparable to the problems of Nigeria. It's necessary to get some perspective. There is simply no question that getting some form of constitutionalism and some form of democratic governance would be better for the vast majority of non-democracies.

To be hobbled by fears and self-doubt seems silly. What one should do with those concerns is channel them into domestic reform programs rather than losing faith in American democracy. It's entirely possible to be a reformer at home and a universalist abroad. Look at Harry Truman.

You said it's necessary to get some perspective. Can you provide some? How imperiled is our democracy?

American democracy has always been safeguarded by strong institutions that protect liberty and it's also been enriched and ennobled by a whole set of informal institutions that Tocqueville called intermediate institutions -- everything from political parties to rotary clubs to choral societies to bowling leagues. If those intermediate associations wither away, if the sense of the civic culture of America decays and is replaced by a kind of polarized populism in which each side is simply trying to use the political system as an arena where you simply have to capture the government however you can, then American democracy is impoverished and loses some of its vibrancy. It doesn't mean American democracy will become Nigerian democracy. It means it won't live up to its promise.

Am I right to see in your book a defense of the power of elites?

I think I would describe it this way. Every society has elites. That is simply a fact of life. People who run the corporations, who run universities, govern in Washington and the state capitals, who are editors and writers, have a disproportionate influence over the life of the nation. To pretend that you don't have elites only does one thing -- it absolves the elites of any sense of responsibility, any sense of having to consciously adhere to a sense of public spiritedness.

I'm not somebody who sees much value in pointlessly bashing elites whether they're conservative or liberal. One of the more interesting shifts I point to in the book, is the shift from a dispassionate, bipartisan elite that founded so many national institutions to the situation today where it's considered almost banal and boring to try to be bipartisan and solve national problems. The heat is all in trying to be as polarizing as possible.

How much of that shift is a result of the rise of the conservative movement? You write about think tanks like the Council on Foreign Relations and the Brookings Institution "that were designed to serve the country beyond partisanship and party politics." Now the most powerful think tanks are right-wing outfits like the American Enterprise Institute, which are fiercely political.

It's an outgrowth of the fact that many of these national institutions became excessively liberal and lost their sense of being bipartisan. Perhaps that's because liberalism so dominated the culture that it went unnoticed, but the reality is that many of these institutions became lopsidedly liberal. That produced a conservative counteraction that is now producing a liberal counteraction.

Really? Where is that liberal counteraction?

You're beginning to see it in places like the American Prospect magazine. But I agree this is an era of conservative ascendancy. There's no question about it.

Isn't there an irony at the heart of your argument, in that it requires people to mobilize against some of the power that's been delegated to them?

The most important thing that could be done is to make the system of government less open and hyperresponsive, by which I mean give people in government some degree of leeway to make judgments. If you look at Congress, by opening up Congress to the degree we have done, we've only opened it up only to special interests. The average American doesn't send 20 faxes a day to his congressmen, but various narrow interest groups do.

The manner in which some of the thorniest problems in the United States have been solved, like major tax reform, military base closings and some judicial issues, have often involved politicians agreeing not to pander and committing themselves to a process by which they're not trading votes to interest groups or campaign donors.

There's something very important for Americans to understand: You can have a more democratic process but actually end up with a less democratic outcome, because the system gets captured by those who know how to play the system.

But do you really think Americans would accede to less democratic processes? Do people ever vote to curb their own power?

It would mean recognizing that some of this populism has gotten us nowhere. Some of this openness has produced dysfunction. Look at California. It's a poster child for democracy run amok. A state that used to be one of the most well-run in the country is now on the verge of collapse. The educational system is a mess, it cannot pay its bills, and it's because of this strange system of government where everything is done by initiative and plebiscite. The Legislature has no control over anything. Do you really want a state where everything is decided by plebiscite?

It's not simply the case that more democracy is always better. The public can understand that. What are the three institutions that the public most admires? The Supreme Court, the armed forces and the Federal Reserve System. What do all three have in common? They're insulated from public pressure and can therefore act somewhat independently of it. Sometimes in democracy less is more. There needs to be some insulation from the day-to-day pressure of public opinion polls.

Your book also touches on the democratization of culture in the age of celebrity, where buzz is taken to be the measure of worth. Meanwhile, you're being written about like a pop star. In her latest column, Tina Brown talks about your "Bollywood sex appeal" and calls you "New York's hot brainiac." Have you become an example of the phenomenon you're writing about?

What does it take to get Hollywood good looks? Look, I hate it. I hate it. What can I say -- when you're trying to sell books, you're out there in the public and people have the freedom to write about you as they wish. I have to confess that I haven't been that thrilled about that part of this.

After the book is done, I will very happily retreat back to the position of being a writer whose public persona is shaped by his own voice. I've found it unsettling to be constructed by other people, but I don't think that there's any danger of my becoming any kind of a mass phenomenon. Let's not kid ourselves.

Shares