It was bad enough that writer Peter Biskind psychically peed all over the Sundance Film Festival in his new book. Then he jinxed producer Harvey Weinstein -- a man rotund in both personal girth and temper -- from a shot at yet again walking onto the stage of the Kodak Theatre to collect another Oscar for best picture.

In a Salon interview last week, Weinstein tried to spin the Academy Award nominations as an overall win for Miramax ("City of God" was a surprise nominee in several categories). But the fact remains that Weinstein's big-budget baby "Cold Mountain" was not a nominee for best picture. Or best director. Or best actress. It only got a shot at best actor (for Jude Law), and best Zellweger (uh, sorry, I mean best supporting actress), and some "minor" technical awards like cinematography and editing, not to mention original song and original score (and as we all know, Harvey can't sing).

"I don't feel like dumping on Harvey and crowing over him," Biskind says over the telephone last Tuesday afternoon, shortly after the Oscar nods were announced. "You have good years and bad years, and this is not shaping up as a good year for him." Pause. "I liked 'Cold Mountain,'" he goes on. "I'm surprised, frankly, that it didn't get nominated. I think [Anthony] Minghella is a really good director. He's a smart guy with a good cast. Those battle scenes in the beginning were right up there with 'Saving Private Ryan.' Is this not what you want to hear?"

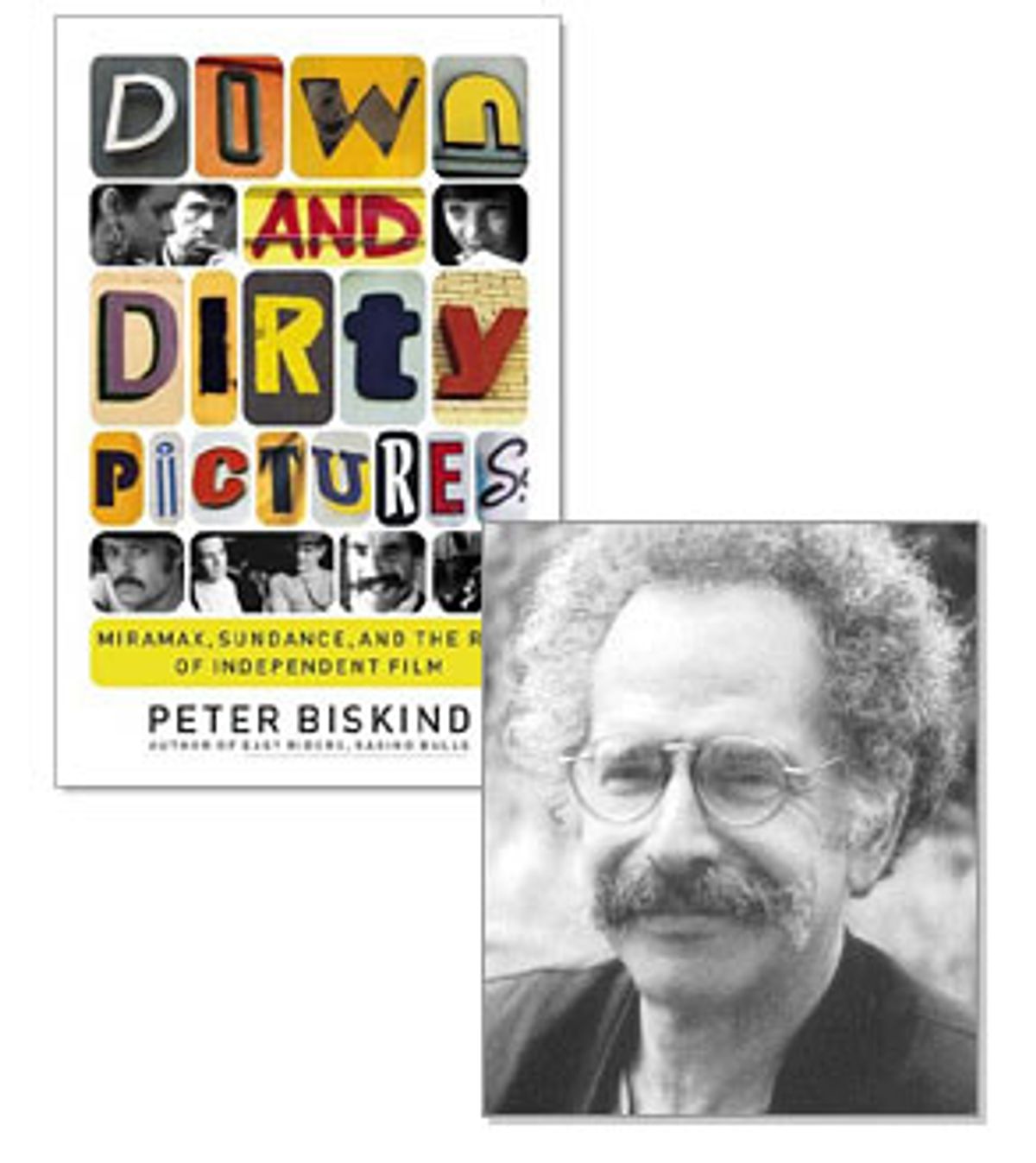

No, no, no. We have no anti-Weinstein agenda. It's just that he figures so notoriously in Biskind's new book, "Down and Dirty Pictures: Miramax, Sundance and the Rise of Independent Film." In its pages, Miramax chief Weinstein is portrayed as the screaming Attila the Hun of independent cinema. Even worse, he partnered with Sundance founder Robert Redford, who is portrayed as a vapid golden boy now pushing 70, who only founded the Sundance Film Festival because the mountain he bought in Utah didn't get enough snow to turn it into a ski resort.

When this year's Sundance festival opened two weekends ago, Biskind's book cast a terrible pall over the opening proceedings. Weinstein, some said, blubbered around contrite like some Ralph Kramden at Alice's funeral, while Redford just lay low, like an aging ski bum minus Viagra. The days of quitting your day job at Blockbuster and maxing out your Visa card to produce a Sundance-worthy masterpiece of American cinema seemed dead and buried.

Yet by Wednesday of Sundance week, Biskind was forgotten, replaced by the buzz over "Open Water," a quasi-"Jaws" remake shot on a shoestring by a Brooklyn couple who used real sharks as props. Several miles east of Park City, presidential hopeful Howard Dean threw a televised fit that made even Weinstein's temper seem as threatening as a stick of cream cheese. At festival's end, the only film of note appeared to be a documentary about a man who ate Big Macs for a month, not exactly the kind of film that gives us the next Quentin Tarantino, let alone the next Redford.

Salon first interviewed Biskind the day before Sundance began, when halfway across the country Weinstein still believed that -- regardless of what Biskind had written about him -- he still had a good shot at an Oscar nomination. Biskind talked to us at the legendary White Horse Tavern in New York. With his fuzzy hair and even fuzzier mustache, he looked like Gene Shalit's doppelgänger. We sat under a photograph of a drunken Dylan Thomas, and Biskind warned he'd have to leave in 45 minutes to make a CNN taping.

So is Harvey Weinstein your Macbeth?

More like my White Whale. My Moby Dick.

What's the difference between Weinstein and Jack Warner? Or any other Monroe Stahr-style producer from the 1930s?

For one thing, the context has changed. In the 1930s, extravagant mogul behavior was taken for granted. It was a much more rough-and-tumble era. Now Hollywood is buttoned-down and corporatized, so Harvey stands out like a sore thumb. He probably would have fit in really well in the 1930s. Harvey is cut from the same cloth as Jack Warner or Louis B. Mayer. No question about that. But there is a ferocity, an out-of-control quality, in Harvey that you don't find in the old moguls.

Does the average Joe really understand the difference between independent cinema and the studio days of "Sunset Boulevard"?

The studio system started to disintegrate after World War II. A Senate decree separated the studios from the theaters. Then the attendance started to slide. Then the rise of television. The [McCarthy-era] blacklist. It all started to go to hell in the late 1940s and throughout the '50s. By the 1960s it was a total mess. And then you have the new Hollywood.

So the new Hollywood is corporate?

What I'm calling "new Hollywood" is the 1970s people. In those days, studios weren't corporate. The corporatization trend was just starting. TransAmerica bought United Artists. Gulf & Western bought Paramount. But at the same time, in the case of Gulf & Western, Charlie Bludhorn, who ran it, was as crazy and mogul-like, and took as much interest in the studio, as any "Last Tycoon." He was a real character in his own. I think TransAmerica was similar to what we have today, sort of a faceless corporation.

Say I work at Blockbuster Video. If I can get my orthodontist uncle to bankroll me $20,000, can I become the next Quentin Tarantino? Or are those days over?

It's harder. If you're as good a screenwriter as Tarantino, write a script and get people interested in it, and get a movie star attached to it -- which is what Tarantino did with "Reservoir Dogs" [in 1992]. He got Harvey Keitel attached to it. I don't think the film would have gotten made without Keitel. Well, I take that back. Tarantino says he was so determined to make the film that he would have shot it on toilet paper.

I think it's both harder and easier today to make independent films. There are more people doing it. The way has been paved. The trail has been blazed. People know it's possible and they see the rewards if they're successful. The same way, I think a film like [Kevin Smith's] "Clerks," which was made for $27,000 with no stars by someone completely unconnected to the movie business -- never been to film school, and had very little family money -- I think those days are nearly over. Everyone says -- and I think that it's true -- you couldn't get "Clerks" into Sundance today. The bar has been raised. The movies are glossier. The budgets are higher. They have movie stars.

How was your first book, "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls," about the wild outsiders who saved Hollywood film in the 1970s, received by the movie industry?

I think it was received very well. Some of the people it focused on were unhappy. The Robert Altmans of the world, the Peter Bogdanoviches. Some people were very cool with it, like Warren Beatty. Martin Scorsese was pretty OK with it. He wrote me a note, and I heard through Robbie Robertson that he was fine. Scorsese took a grown-up attitude: "If you can't take the heat, get out of the kitchen. I did live through that era. I did do that stuff. Someone is going to write about it. It's not the end of the world."

Other people were more freaked out. I always thought the best comment about "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls" was -- not to drop names -- when I ran into Oliver Stone. And he told me that he had run into Billy Friedkin [i.e., William Friedkin, director of "The Exorcist" and "The French Connection"] in the men's room at some hotel right after Oliver had read "Easy Riders." Oliver said, "I read this book. I see you acted like a real motherfucker in the 1970s." And Friedkin just turned to him and smiled and shrugged, "Eh, it's just a book."

I think that's a healthy attitude. I never understood why Francis Coppola would get so upset. If I had made the two "Godfathers" and "The Conversation" and "Apocalypse Now," I wouldn't give a shit what people said about me. They could say that I was a pederast and I wouldn't care. You make films like that, you're safe for life, I would think. But apparently people don't feel that way.

Just to refer to my experience, I wrote a book on the Talking Heads where I portrayed the bass player Tina Weymouth as the villain. That hadn't been my original intent, but she would go off on these maniacal rants and claim she wrote songs that she hadn't, and then insult me. So finally I thought, "That's it, bitch. I'm going to reveal how insane you really are." With this book, did you know Harvey was going to be your White Whale from the beginning?

Yes. I already knew Harvey a little bit. As I said in the preface, I was going to write a story about Miramax in 1991 for Premiere magazine, but I was discouraged because they withdrew all their advertising. The next thing I knew I was Harvey's editor as he was writing columns for me. I would run into him. And he has this reputation, you would hear Harvey stories constantly. I knew before I started that this had to be a major focus of the book. I knew what I was dealing with. Harvey can be so charming and seductive. You'd blurt out atomic secrets if he asked for them.

How could you actually dig up dirt on a saint like Robert Redford?

Well, he was my Tina Weymouth. I wrote this article for Premiere in 1991, on the 10th anniversary of Sundance. I thought my article would just be celebratory about what a great institution Sundance was. Then I started talking to people who actually worked for Sundance. People who had been fired. I started talking to filmmakers. The picture I got was totally contradictory to what I was expecting. I just went with that story. I had no preconceptions. If anything I was predisposed to like Sundance. I was just flabbergasted. Redford was so difficult to work for that some people hated him. He was a micromanager. A control freak. You couldn't get anything done without his approval or OK, but you could never get his approval or OK, because he was never around. He was off shooting someplace. Or he was indecisive and wouldn't make up his mind. It was infuriating. That was across the board. I must have talked to 15, 20 people that had the same story.

Now as far as filmmakers went, Steven Soderbergh had this legendary falling out with him after Redford scrambled to sign Soderbergh up after "Sex, Lies, and Videotape" -- Redford was completing with Sydney Pollack (his good friend) -- and Redford finally got onboard with "King of the Hill." Then he and Soderbergh had a dispute over how much of their salary they were going to defer. During postproduction, Redford asked to see the movie abruptly over a weekend, and then never got back to Soderbergh on whether he liked the movie. And then Redford tried to take his name off the film. Compounding that, there was a tussle over "Quiz Show," which Soderbergh was slated to direct. Redford essentially ended up taking it away from him. And here is this guy who is supposed to be the champion of independent film. This wasn't the only instance of this happening. Robert Redford wasn't this great benefactor of independent film. He had other agendas going.

How does someone tell you something about Robert Redford off the record?

What do you mean? They say it's off the record ...

But there is a casual "off the record," and there is the "they're gong to burn me at the stake if I tell you this" off the record.

There is always this litany of interviewing someone on the record, and then suddenly the conversation stops. And you know there is a story that they won't tell you, and you say, "Well, you can go off the record." You have to do this whole song and dance. "How can I trust you? I'll get roasted alive if this ever gets out." You can't keep working in this business, as you know yourself, if you burn your sources and the word gets around.

How much did you not put in the book that you could have?

A lot. Partly because I didn't have the whole story. I just didn't have time. It's inevitable. There's lots of stuff about the 1970s that I didn't put in "Easy Riders." I was told this unbelievable story. [Tells a long story, off the record, about an act of debauchery involving major filmmakers at a Chinese restaurant on Hollywood Boulevard.] The story was totally off the record, and I did not use it. It killed me not to use it.

There was no way to get confirmation from a waiter or something?

No. There weren't enough people involved. It was so frustrating, but sometimes you just lose that stuff. But ultimately, a year later -- who cares? Nobody misses the story because they didn't know about it to begin with. I always remember this thing that George Lucas said about "Star Wars": "You're lucky if you shoot 10 percent of what you have in your head." The same is true with these books. For all the stories in the book, the real truth -- the deeper layer -- there's much, much more stuff and it's much more outrageous than what is actually in the book. Harvey would quote the line from "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance": "Print the legend." He'd say, "I know you don't give a shit what the truth is, you're just going to print the legend." Sometimes he'd say something himself, and then say, "That's not really what happened, but it sounds good, so use it." You do try to find out the truth as much as you can. There are so many versions of the "truth." Then there are the out-and-out lies.

How often were you lied to?

A lot. I tend to be a credulous person, but I've learned to be more skeptical. Sometimes nothing anyone tells you is the truth. There are these legendary gray areas: How much did Robert Evans really have to do with "The Godfather"? Those famous controversies that you never get to the bottom of. Evans says one thing, Coppola says something else. Then you start interviewing peripheral figures; they all contradict each other. And it all depends on whether they're friends of Evans, or friends of Francis.

So I heard rumblings that "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls" was inaccurate. When I tracked down the source, it turned out that someone who knew Pauline Kael remembered her complaining that you got her story wrong.

That's a good example because I believe that Pauline Kael lied to me. I had asked her how many scripts she read and which ones they were. I can't remember what the film was. I think it was a Robert Towne script. She made a lot of suggestions [to Towne], and then she reviewed the movie when it came out. That is really kind of outrageous. I asked, "How often did this happen?" She said that was the only time. Then later, I read an interview with Paul Schrader, and he said he sent her a copy of "Taxi Driver." I'm sure there are many other scripts that were given to her. She just bald-faced lied to me! This little old lady! [Laughs.] Pauline Kael, the greatest movie critic that ever lived. The Pauline Kael story has never been written. She still has devoted followers -- Paulettes.

Do you like Martin Scorsese?

I like him a lot.

Scorsese stopped thinking like an independent filmmaker long ago. I mean, geez, "New York, New York" was him being Vincente Minnelli.

Scorsese has always been one of these people who has been fascinated by Hollywood movies. If you know as much about Hollywood movies as he does, you have to admire his system. He wants to make a musical. He wants to make a western.

[Biskind's cellphone rings. He answers with a flick of the wrist like Captain Kirk. Then: "Yes. OK. Right. Right, right, right. OK. Right. I did, yeah. Yeah, not much later, but I have to leave at 4:30." He flicks it off.]

[Disappointed.] There's no CNN. We don't have to stop on the dot at 3. I've been preempted by an interview with Spalding Gray's wife. [The actor is missing and presumed a suicide.] Anyway, I think Scorsese has always been pulled in the direction of being a Hollywood director. At the same time, he doesn't really have a Hollywood sensibility. So he's always been pulled between those two poles. There is stuff in "Gangs of New York" that is very much too tough, too dark, for Hollywood.

In the late 1940s, didn't right-wing pundits demand that Hollywood movies stop glorifying failure, or being too dark?

You had all those dark, dark film noirs with unhappy endings. And everyone would get killed. Or live with betrayal. A lot of the heroes of those movies were down and out: John Garfield. I don't think Hollywood today is interested in real people. Independents seem less and less interested in real people. Look at "Something's Gotta Give," which is the last Hollywood movie I saw. The characters live in the Hamptons and just go from one expensive restaurant to another. They're all rich. That's the milieu that Hollywood feels most comfortable in, and what audiences want to see. The only time you see ugly people in "The Lord of the Rings," it's the Orcs.

Isn't "Lord of the Rings" a studio film?

Weirdly enough, it started life as a Miramax movie. It almost was a Miramax movie, but it was too expensive. Harvey tried to kick Peter Jackson off the movie and give it to John Madden.

How did you get your start as the official historian of the last 25 years of cinema?

I was working at Premiere, and I was the same age as a lot of the directors I wrote about in "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls." I saw most of those movies when they came out. I obviously loved them. I always wrote about them. When I would go to do an interview [with Hollywood people from that period], they would all talk about the old days, how great they were. I remember Warren Beatty saying that in the 1970s there was actually social pressure from his peers to do "good work." One of the points I make in "Down and Dirty Pictures" is that the phrase "selling out" has no meaning anymore. It used to be a really bad thing. The worst thing you could do as a director or a screenwriter was to sell out. In fact, the director Alexander Rockwell more or less said that to Tarantino when he became successful with "Pulp Fiction." "You have to be very careful. Don't sell out." And Tarantino just looks at him like he doesn't know what Rockwell is talking about.

In the 1970s people were concerned about selling out. They didn't care about their careers as much as they did their integrity. I used to listen to those people rhapsodize about those 1970s. I thought the back story of all these filmmakers was the real story, not what they are doing now. Most of them were in a downslide in terms of their careers [by the mid-1990s, when "Easy Riders" was written]. I thought it would be really cool to do this whole era that came after the death throes of the studios.

Let's follow the money: When MGM made a musical in the 1930s, the money came from MGM itself, right? They didn't have to go out and try to hustle up the bucks?

They went to Wall Street. They had a credit line with some Wall Street broker or creditor. In those days, the business offices were in New York and the studios were in L.A.

But MGM didn't have to go to a banker and say, "Hey, want to invest in this new picture called "The Wizard of Oz"?

No. They didn't do it on a film-by-film basis.

Now it seems like it's a little of both, isn't it?

Sometimes it's a slate of pictures, sometimes it is film by film. It's quasi-independence. You get part of the money from the studio, and then raise the rest of the money elsewhere. You go out with your hat in your hand to investment bankers. To the Japanese and Germans. You get a lot of foreign money.

This whole post-"Last Tycoon" era has lasted much longer than the studio system did, right?

The studio system ended by the late '40s. So it lasted for 15 years.

Who are the heroes that are going to keep cinema going?

David O. Russell. Wes Anderson. [Pause.] What's his name? Miguel Arteta. I like his films. I'm forgetting a bunch of others. Quentin Tarantino. Soderbergh. It's hard to know what direction those last two are going to go in, but they certainly have lots of talent. [All of these appear in "Down and Dirty Pictures."] I think one of the achievements of the 1990s was to create an infrastructure, a support structure for these people so they can actually have a career instead of one good film. Then you have another generation coming up behind them, like Sofia Coppola.

What did you think of "Lost in Translation"?

I thought it was a great example of the hybrid of the new Hollywood. It used a big movie star [Bill Murray] who got a lot of attention, and at the same time it was a very un-Hollywood movie. There is virtually no plot. Nothing happens. There is an inconclusive ending. You'd never get that film made in Hollywood. I didn't like everything about it; I thought it was all atmosphere. I just thought it was nice that she pulled it off.

I really felt like I was back in the 1970s.

In a good way?

Oh, yeah. The shots were held longer, like in the '70s. It wasn't bam bam bam. I could watch a medium shot of Bill Murray standing in an elevator full of Japanese businessmen for about 10 minutes.

Right. It was slow. Exactly. [To waitress.] Can I have more coffee?

Waitress: Yes. I'm making a fresh pot.

Great. Because this tastes like battery acid.

Waitress: Yeah. It's not good coffee to begin with. [Both Biskind and the waitress begin laughing.]

Were you living in New York in the late '70s?

Yeah. I used to be involved with the magazine called Jumpcut, which was printed on newsprint. I used to distribute it myself.

Yeah! I worked at Cinemabilia bookstore, on 13th Street. I remember you lugging in your big piles of Jumpcut. So this was what film culture was like 20 years ago. I'm 19 years old, 20. Working at Cinemabilia for $6 an hour, sneaking into the back to read Jumpcut. Reading about Coppola's take on camera angles. Robert Altman on dialogue. I'd go to the movies four nights a week between Saturday and Thursday, and every Friday I'd be at some film's first opening night. I never thought about how much a movie cost to get made. If it went over budget. Whether it lost money. Who cared about that stuff? Then suddenly "Heaven's Gate" is the world's biggest bomb, and news about a film's budget became as interesting as its artistic goal. Now every Monday I'm reading the Times business section to check out the weekend film grosses.

The same was true with me. I was completely into film from an aesthetic point of view. I worship those people in that same way: "God! Why did you put the camera up here!" That's the way Peter Bogdanovich wrote all those books where he knew more about old movies than the directors who made them. Film technique was the center of gravity if you were a cinéaste in those days. You weren't interested in budgets or the business part of the industry, because it was corrupt and irrelevant. Nor were you interested in people's personal lives. All that changed as celebrity journalism got involved in the '70s, '80s and '90s, and the only thing that people were interested in was the money and personal stuff. But how many books can you read about Scorsese talking about where he put a camera on any given film? There are 10, 15 books and that is all they talk about. After a while it gets boring.

Also, as you get older you realize perhaps the biggest triumph of, say, "Lost in Translation" is that she managed to get the money to make it.

Well, she did come from that family. She did have a leg up. It doesn't hurt. One thing that surprises you about books -- when "Easy Riders" came out, and Freidkin said, "It's just a book," I sort of felt the same way. Everyone says that nobody reads anymore and book culture is dead. I was amazed and gratified that so many people were interested in a book. It was much different than publishing a magazine article, which I had been doing for 20 years. The thing is there and it's gone when the next issue comes out. A book is actually treated like a substantial contribution -- it's not just forgotten the next week. If you spend a lot of time writing books, that's nice.

Well, the main criticism I've read about your book is that it's too gossipy.

One person's gossip is another person's interesting personal history. To understand personal films you have to understand what those people are like. Certainly you had to understand the drug culture to understand why the careers of so many 1970s figures went up in flames. I'm not apologetic at all. When you read a biography of Picasso you want to know what he was like. Was he a philanderer? He treated women this way and that way. That's what biographies are for. These people were historical figures. Public figures. I'm not saying it's fun to have your sex life written about. I wouldn't like mine written about.

So there are drugs and sex in your past?

Well ... sex -- like everybody else. I wasn't a big drug taker. I always preferred liquor.

Shares