Among the half-million teens who struggled through the SATs a week ago,

it is unlikely that many had any idea of the scandal being frantically

swept under the rug by the makers of the seminal college entry exam. On

Aug. 31, the Wall Street Journal broke the news that the Educational Testing Service was conducting research for a project that would factor students' socioeconomic background into their SAT scores. Using 14 different categories, including family income and parents'

education level, each student would be given a predicted score that colleges could then compare to the student's actual score. Students scoring 200 points higher than predicted would be labeled as "Strivers" -- i.e., kids who despite difficult circumstances still demonstrate scholastic potential. The ETS was creating two versions of the Striver program: one that was race-blind, and another that made students' race and ethnicity integral to the equation. The race-blind model would be especially useful in states such as California and Washington, which bar affirmative action preferences at public schools.

Although the Journal put the story in the B section, the next day several newspapers in major cities picked up the story, fomenting a minor scandal in admissions circles. ETS promptly issued a press

release stating that the Journal's story was "misleading," and that "there

is no product, program, or service based upon the Strivers research."

However, the company was too late. Within a week, Strivers was being hotly debated

in editorial pages nationwide. And by Sept. 4, the conservative New York

Post had condemned the program, declaring that it "gives minorities extra

points solely because of the color of their skin" -- which, they concluded, was "horrific."

In the midst of all this Sturm und Drang over the racial dimensions of college admissions, few voices in the debate ventured to speculate on ETS's underlying motivation for developing the Strivers program. Although at many colleges the SAT remains a primary admissions criterion (along with high school grades), this hasn't protected ETS financially. Last year, more than 2 million high school students took the SAT, the largest number so far. Everyone paid the same fee, $23.50, so nonprofit ETS raked in at least $47 million in fees alone. Despite this apparent windfall, the organization is struggling. Last year, 57 employees were fired by ETS, and another 58 budgeted staff positions remained unfilled. Non-salary

benefits have been cut, and cost reductions have been made in the computer-based testing

program. By June 30 of this year, ETS still had an operating deficit of $7.7 million. And, in an internal newsletter dated Sept. 16, this deficit was called "encouraging news"; the

company hopes to break even by fiscal year 2001. Evidently ETS is flailing; like many companies, it may hope that improving its product will increase sales and profits.

Recent studies on the efficacy and fairness of the SAT have not improved ETS's prospects. Originally envisioned as a tool of our democratic meritocracy, the SAT has been attacked as a biased, inaccurate tool of academic measurement. Not only do white and Asian males tend to do substantially better than females, Latinos and African-Americans, but the test does not accurately predict students' long-term academic performance. There are already 284 colleges that do not

require SAT scores from would-be freshmen, and every year a few more schools drop the

admissions mandate. Such trends leave the future of the ETS looking increasingly precarious.

A Strivers program would have made the test more attractive to the many schools that have dropped the SAT because of its racial and gender bias. It also would have appealed to state schools scrambling to target promising minority students -- without the costly and time-consuming process of searching through applications individually. For ETS, this would have been a major boon, in terms of both money and reputation.

So why did ETS retreat so hastily as soon as it came under the press spotlight?

According to Nicholas Lemann, author of "The Big Test: The Secret History of the

American Meritocracy" -- 350 pages devoted to ETS and the evolution of the SAT

since its inception in 1926 -- ETS is afraid of looking like "social engineers." Most selective colleges, he explains, already have an informal strivers program; the idea of quantifying racial and economic factors, however, seems difficult if not impossible.

"Strivers," Lemann says, "makes too explicit what colleges do. There are things

you can do in a subtle way that you can't do in an open, numerical way.

It's like, if a guy goes up to a woman in a bar and says, 'What's your sign?' --

vs. a guy who goes up to the same woman and says, 'I want to have sex with

you.' Some things are better done in a subtle way."

But such subtleties are beyond the means of large state schools, which purportedly cannot afford a large admissions staff to peruse each applicant's portfolio; instead, many of these schools now screen applicants with a numerical formula based on test scores and GPAs. Critics of standardized tests charge that these schools don't have their priorities straight -- and that a newfangled test can't make up for looking closely at individual applications, despite the expense. "Can they afford fat coaching contracts and big sports stadiums?" challenges Bob Schaeffer, the public education director of Fair Test, a standardized testing watchdog group.

Schaeffer thinks that the existence of the Strivers research opened the SAT to yet more criticism of unfairness. "ETS is gun-shy when anything suggests their

test is not a flawless product," he says.

When confronted about the status of the Strivers program,, a spokesman for ETS

ducked the question, saying that he believed the research was proceeding, but reiterating that

ETS has "no plans to utilize it. There is no product."

Meanwhile, admissions offices in public universities in Texas, California and Washington are struggling to diversify their student bodies while obeying affirmative action bans. Since black and Hispanic students score an

average of 100 to 200 points lower on the SATs than whites and Asians, Texas schools are maintaining diversity by automatically admitting students in the top 10 percent of their high school class. A similar tactic has been adopted at the University of California, which accepts seniors in the top 4 percent of their classes. Although it's a remote possibility, it is conceivable that powerful states such as California could someday drop the SAT all together. And that, says one industry observer, "would be a bad day for ETS."

Predictably, those who suffer the most from debilitated affirmative action

laws and biased tests are the students themselves. Test and application fees are already burdensome to many families; costly preparation classes are out of the question. Furthermore, child psychiatrists theorize that impoverished minority kids

realize by the third grade that they are being marginalized. Without

exceptional parenting, these children are unlikely to jump faithfully into

the waters of a mainstream education -- and standardized tests presume the

takers are already capable swimmers. Anthony Carnevale, the ETS vice president who headed the Strivers project, told the Wall Street Journal that "a

combined score of 1,000 on the SATs is not always a 1,000 ... [The Strivers program] is a

way of measuring not just where students are, but how far they've come."

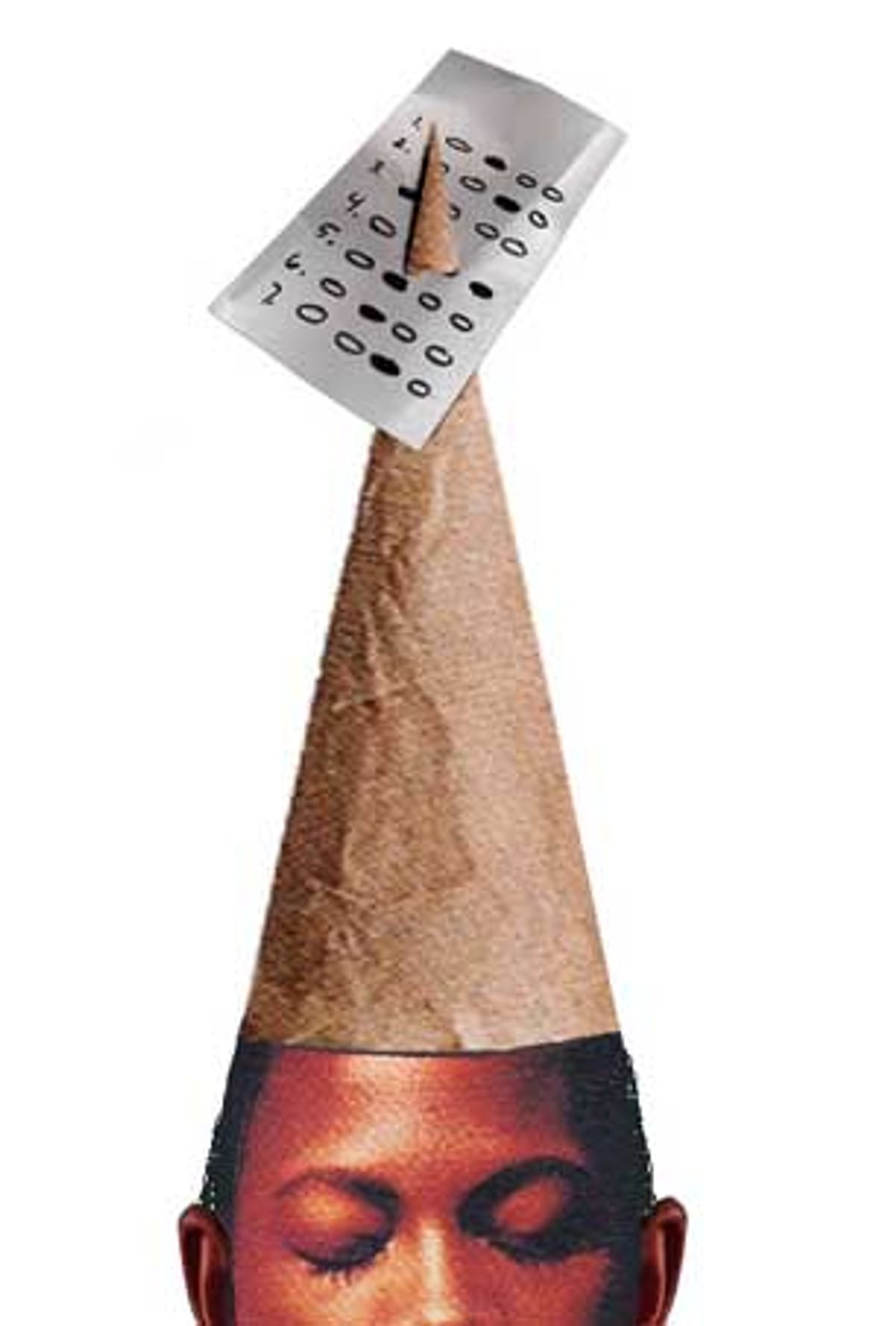

Perhaps it was this blatant admission that standardized tests are millions of Scantron bubbles away from being true gauges of potential academic ability that forced ETS to disavow its Strivers research. According to Winton Manning -- a former senior official at ETS who worked on a project strikingly similar to Strivers in 1990 and who was hired by the first president of ETS, Henry Chauncey -- "ETS still is carrying verbal and mathematical testing begun in 1934 or '36. I think that's a tragedy."

Shares