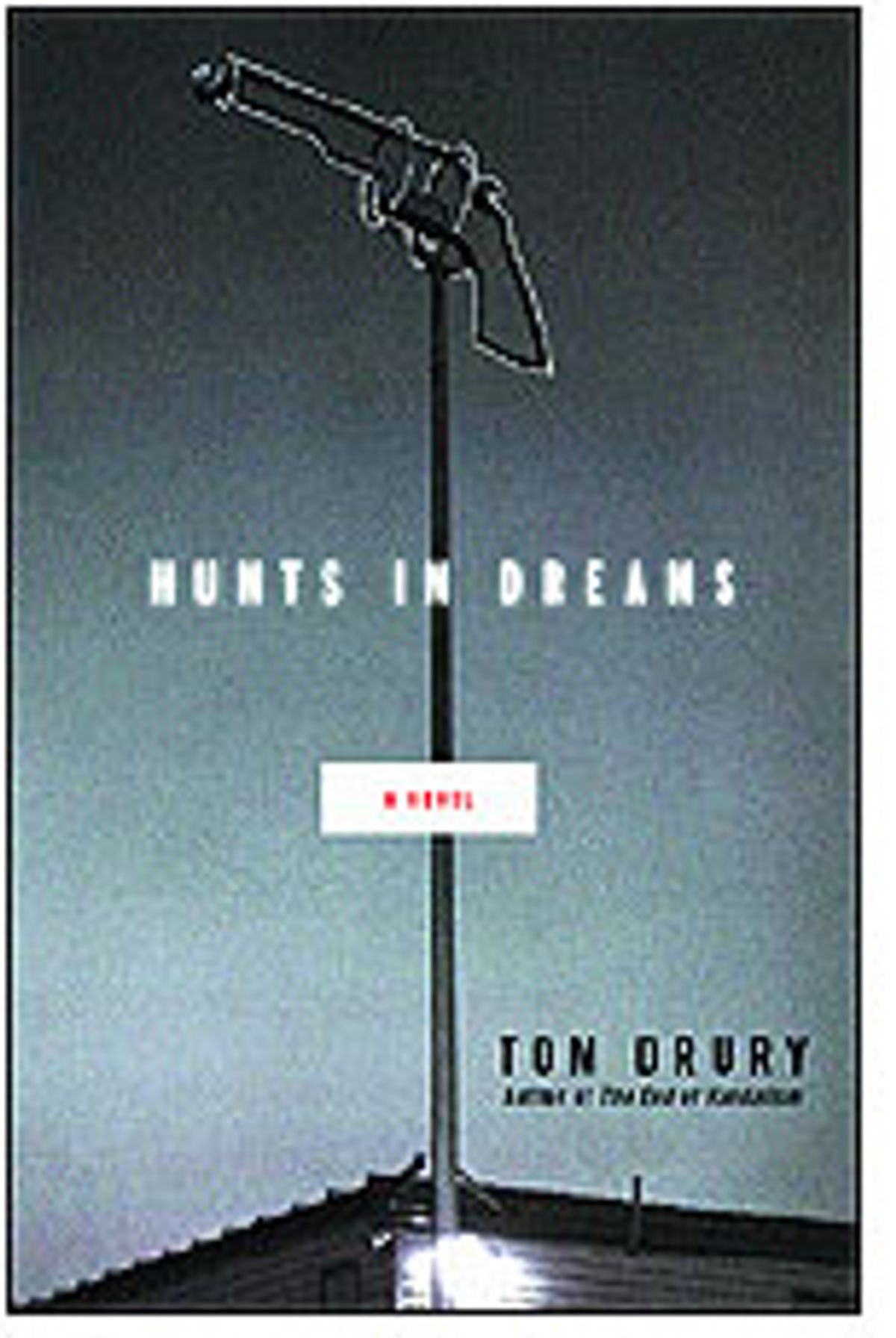

The style of Tom Drury's brief new novel, "Hunts in Dreams," suggests a North American version of magic realism, though nothing magical happens in the book and it isn't all that realistic, either. But it seems open to magic; if one of the characters had seen the future or turned into a porcupine, I wouldn't have been any more surprised than I was by the strangely off-kilter events that fill up the long weekend of Drury's compact narrative.

Drury is in love with the quotidian in a way that's specific to a few writers, painters and filmmakers. You can feel the pleasure he takes in precisely describing unremarkable events and objects -- cutting lumber ("Sawdust flew in furry arcs that coated their arms and necks"), a wooden coat hanger ("The arms were curved and smooth, and the bottom rail was chamfered in with Phillips-head screws").

None of this precision applies to his characters, who are as amorphous to themselves as they are to the reader. "Who am I?" they all seem to be asking, rather desperately. Charles Darling, a not exactly even-tempered plumber, and his more down-to-earth second wife, Joan (holdovers from Drury's 1994 novel, "The End of Vandalism"), live a few miles outside the small Midwestern town of Boris with their 7-year-old son, Micah, and Lyris, the 16-year-old daughter Joan gave up for adoption at birth and who has been returned to her birth mother after her latest set of foster parents were arrested for making bombs. Drury plumbs these characters' thoughts with a sophisticated naiveti that makes the grown-ups seem childlike and the kids oddly mature.

Over the course of four days, Friday to Monday, we follow their somewhat opaque doings, most of them insignificant, a few life changing; as in the real world, you don't know which is which until afterward. Everything is almost funny and at the same time inexplicably sad. Violence hovers; guns play a big part in the plot. Charles isn't above breaking and entering when it suits his purposes. Micah finds himself alone on the town streets late one night. Lyris, cornered by a guy she doesn't trust, threatens to jump off a bridge. The suspense isn't of the TV-show variety, but it doesn't seem quite real, either -- it's something out of a parallel universe that operates according to its own generally benign laws (though with room for tragedy and loss), peopled by garden-variety fuckups who are easy to love because even at their sleaziest they have large reserves of generosity.

Drury's tone hovers just this side of absurdism, flirting dangerously with silliness. I'd like to do him the justice of capturing him in his own words, but it takes several pages for him to get his weirdly beautiful colors vibrating. Still, I'll give it a try:

They drank coffee in a restaurant with photographs bearing the splashy signatures of local celebrities. Dr. Palomino theorized about how hard it would be to wait tables. He said that removing the vermiform appendix was easier than taking a plate of soup to a table, because at least the customer in the appendectomy was out cold. Joan said she still had her appendix, and the doctor admitted that many people keep them for life. The main thing to remember when removing them was to count the sponges. Two men sitting in the adjacent booth moved to another booth.

If there's an off note in Drury's work, it's the awkwardness with which he drags in literary quotations he likes, such as this one from Montaigne: "It is not possible for a man to rise above himself and his humanity ... We are, I know not how, double in ourselves, so that what we believe we disbelieve, and cannot rid ourselves of what we condemn." That's an elegantly concise statement of the book's major theme, but it comes from the lips of Charles' mother, who is not a woman who could utter a sentence like that without embarrassment.

Similarly, the novel's title is out of Tennyson, but Drury doesn't give the reader enough context to make sense of it. He doesn't even identify the poem, which is "Locksley Hall," a semihysterical rant by the young poet about a woman who rejected him for a richer and (he thinks) far less interesting man. Maliciously, Tennyson pictures her trapped and listless while the clod she married sleeps off a drunk: "Like a dog, he hunts in dreams, and thou art staring at the wall."

But the poem is a key to the novel only by contrast. Joan, too, may look like a sensitive woman chained to a coarse husband, but coarse is not how "Hunts in Dreams" leaves you thinking of the man who tells a girl still smarting from her mother's long-ago abandonment, "It was not that she didn't want you but that she didn't know you." Drury has said himself that the image of hunting in dreams means something to him that it didn't to Tennyson -- a striving toward something better. The notion has a dreamlike lyricism, and for all its comical love of the mundane, "Hunts in Dreams" is a dreamlike book -- not in the way dreams are but in the way that life can be.

Shares