Reading "The Madonna of Excelsior" is so enjoyable, so captivating, that by the time you've finished the book (in not much time at all, probably), you'll be shocked to realize you've actually learned a great deal.

Of course, in a certain sense, that's what great historical fiction is supposed to do, right? Take all those bland high school history lessons we ignored like broccoli next to a slice of chocolate cake and use a story to give them a tasty candy coating. Voilà -- knowledge on a stick!

But author Zakes Mda teaches us about much more than the history of his native South Africa in his latest book. Or rather, he teaches us about history in its fullest sense, with all of its deep psychological, emotional, intellectual and personal implications.

Mda selects a small, singular event from the extensive legacy of apartheid -- a court case, in 1971, in which 19 black people from the town of Excelsior were charged with violating the country's Immorality Act, which prohibited sex between blacks and whites -- and with it, he opens a door onto the subtle paradoxes of race, human relations and human existence. By the end of his book, you'll understand not only a great deal more about the past and present of South Africa, but also about people in general, and the intricate emotional forces that shape who we are.

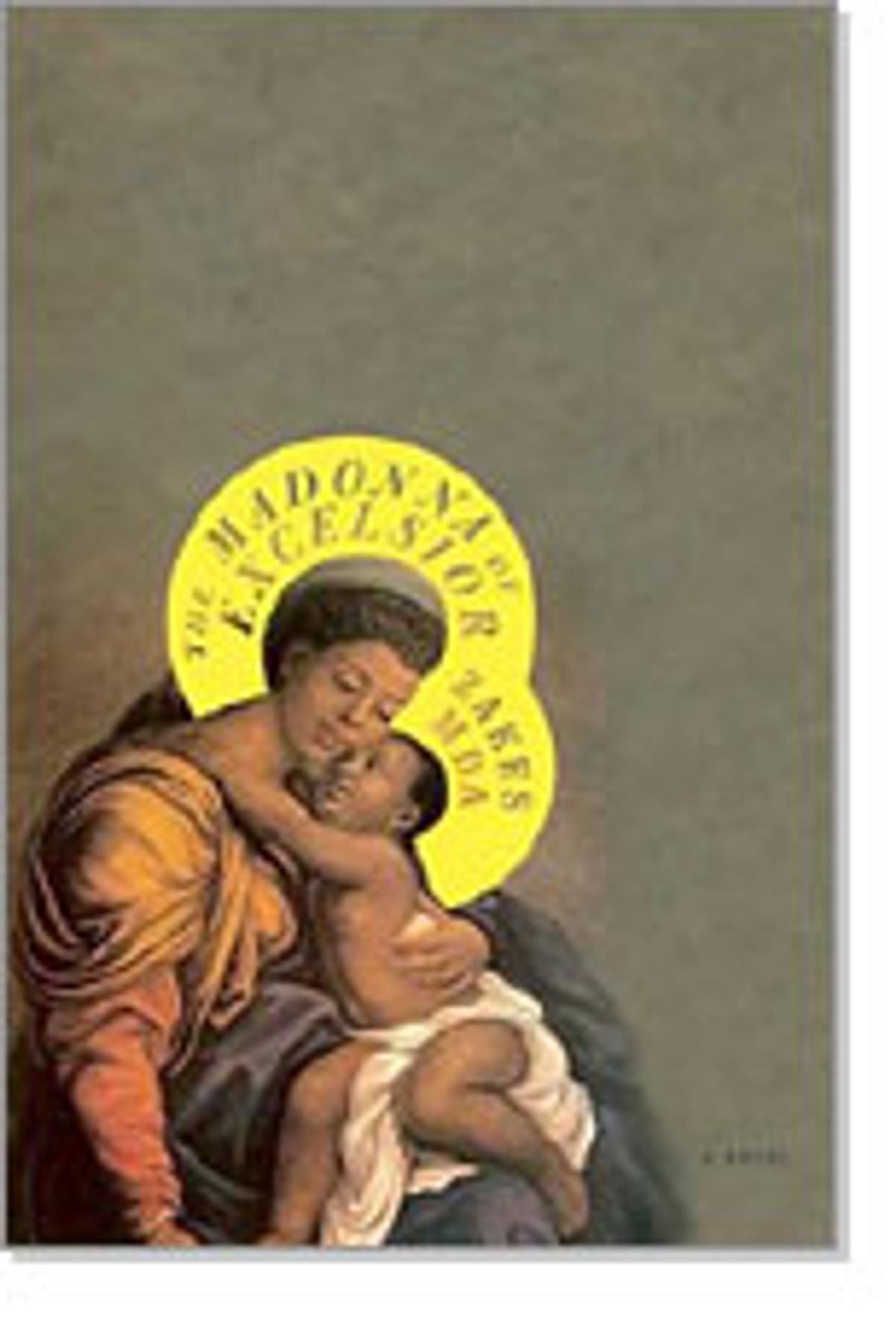

The Madonna referenced in the title is Niki, one of the defendants in the case, who has given birth to a racially mixed (or "colored," in South African parlance) girl named Popi, the daughter of a prominent local Afrikaner businessman. Early on, the narrative focuses on Niki and her struggles to understand a world that is not of her making and not to her liking. This is the most intimate part of the book; Mda draws his character perfectly, bringing us into Niki's mind and heart so that we feel a real, tangible connection with her and her struggle.

At the butchery where Niki works, her boss, Cornelia, suspects her of stealing and forces her to strip naked in front of everyone to prove she isn't hiding any meat. It is this act of shame and disrespect that sows the seeds of the affair -- Cornelia's husband, seeing Niki without her clothes, first begins to desire her; Niki, wanting revenge against Cornelia, gladly accepts the first chance to sleep with her husband. We feel Niki's rage when she's humiliated, just as we feel her triumph when she first sleeps in Cornelia's bed. For us, as for Niki, love and hate become inextricably linked; desire, anger, longing and the forbidden all become intermeshed -- and just like that, just for a moment, we understand the twisted nature of apartheid.

In the second half of the novel, Mda moves to the younger generation; a crucial point of the book is to illustrate how "from the sins of the mothers all these things flow." In other words, there is no such thing as a clean break or a fresh start. Life is interrelated, so a woman's act of infidelity will shape the nature of the child born by it, just as years of institutionalized racism will continue to affect children who are born after the laws are abolished. Once grown, Popi, Niki's daughter, becomes involved in city politics after the fall of apartheid. As a member of the newly integrated city council, Popi joins her half-brother, Viliki, Niki's first child with a black South African man, and her other half-brother, Tjaart Cronje, the legitimate Afrikaner son of Popi's biological father.

Although it is their obligation to lead the city into the future, all three are consumed, in their own ways, by the hatred and anger of the past. Viliki cannot forget his people's oppression at the hands of the Afrikaners; Tjaart constantly laments the Afrikaners' downfall; Popi, neither black nor white, a perpetual outsider, resents her own identity.

The plot begins to move along at a faster pace, which keeps the story engaging, but Mda at times grows a bit distant from his characters, maybe because he has four to juggle instead of just one. Popi, in particular, seems a little incomplete in her transition from girlhood to womanhood; a soft, optimistic streak runs through her that at times feels inconsistent with the fiery disposition that generally defines her character. But these are only momentary lapses, and Mda funnels all of the divergent streams of plot and character into a meaningful, unified conclusion with exceptional grace.

In fact, a portrait of this jumbled hodgepodge of life -- people, their thoughts and their emotions and their actions, never totally sensible or even comprehensible -- is something Mda strives to create in the novel. His own art is paralleled by a character in the book, a Catholic priest who enjoys painting in the abstract style of Flemish expressionists. Each chapter opens with a scene from one of the priest's paintings of average, daily South African life, raised to the level of the divine in a mishmash of sentence fragments and colors and images.

As an adult, pondering the priest's work -- some of which depicts her as a child -- Popi muses, "Why should it mean anything at all? Is it not enough that it evokes?" This, we finally understand, is the true gift of "The Madonna of Excelsior": a representation of life in all of its hues and shades, a picture of humanity more fully resolved than anything found in a history book.

Our next pick A young mother falsely imprisoned for murder provides the link to a string of quiet tragedies in middle-class England

Shares