Back when I worked for a political magazine, a big cowboy-hat-wearing Texan who was some sort of DNC muck-a-muck would occasionally come by the office. While most good liberals take pains to say my name correctly, sometimes overly exoticizing the pronunciation with bizarre emphasis and guttural stops that my own mother couldn't replicate, this particular fellow would just fill in the blank with any name that sounded vaguely Asian-y. Never tentative, he would bellow across the room, "Hey there, Michiko" or "How you doing, Ming Na?" I braced for the day I would hear "How's it hanging, Mulan?" or "What's going down, Madame Butterfly?" "Can I get a whoop-whoop, Kikkoman?" Or maybe simply: "Hello, Kitty."

These days, names like Hayao Miyazaki, animation grand-daddy, or Takashi Murakami, the man whose colorful rendition of the Louis Vuitton print sold purses like crazy and who just appeared on a recent cover of New York Times Magazine, roll off the tongues of urban hipsters and the fashion forward. The Cartoon Network's programming is anime heavy, movies like "The Ring" and "The Grudge" demonstrate that Hollywood increasingly looks East for inspiration, and along the way, the public is becoming enlightened. Even Norelle, last season's resident bird brain on "America's Next Top Model," seemed appropriately embarrassed that Panda Express is, like, Chinese and not Japanese.

And then there's Gwen Stefani.

Stefani, the platinum-blond No Doubt front woman with the undulating midriff, recently released her first solo album, "Love, Angel, Music, Baby," a riotous jumble of everything from '80s bubble-gum pop to hip-hop to "Fiddler on the Roof" gone mad on a pirate ship. And tying all these influences together in one baffling mélange of semiotic ambiguity is her ever-present entourage: Four harajuku girls, or rather, Stefani's interpretation of Tokyo street fashion in the Harajuku district.

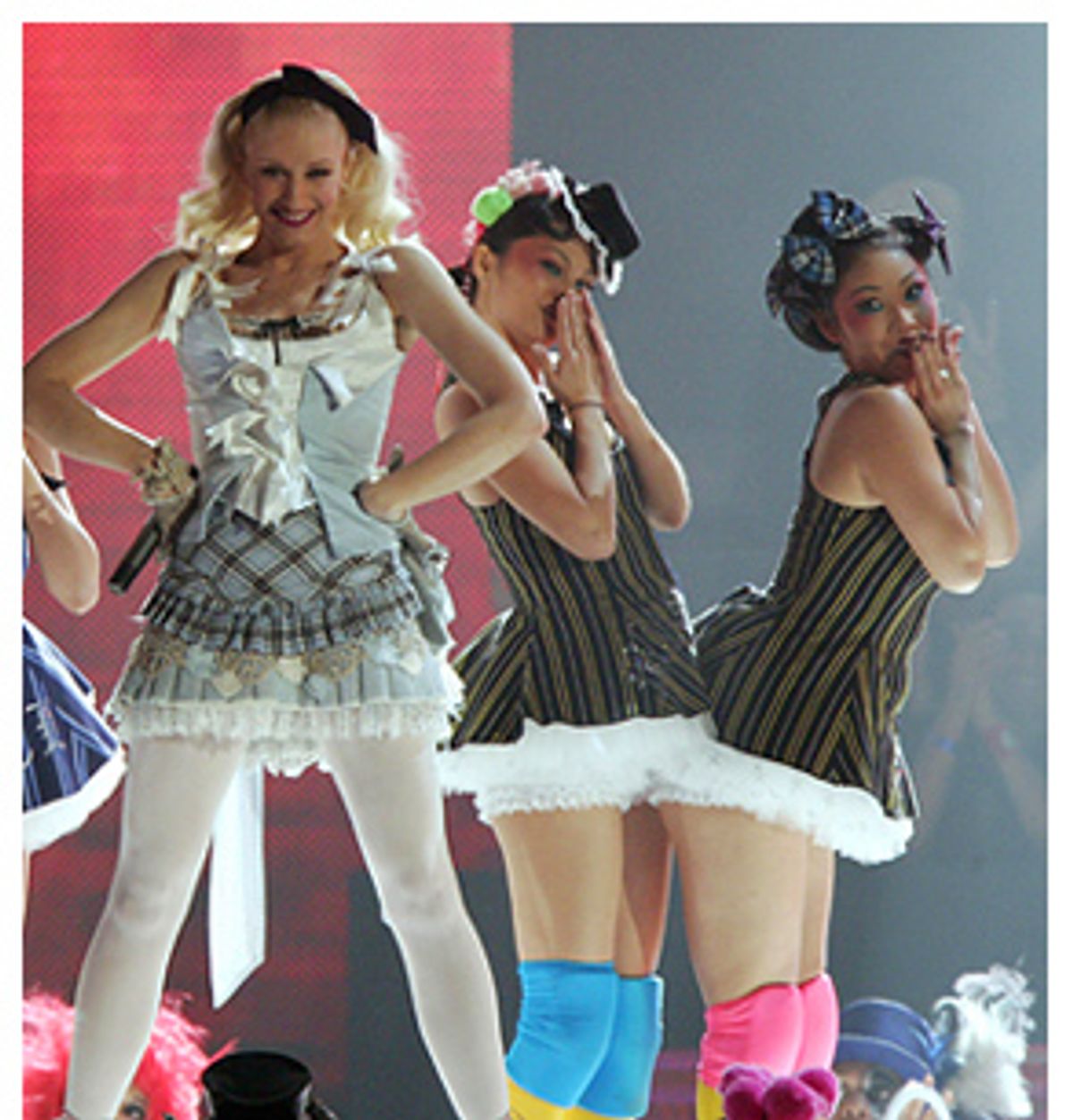

They shadow her wherever she goes. They're on the cover of the album, they appear behind her on the red carpet, she even dedicates a track, "Harajuku Girls," to them. In interviews, they silently vogue in the background like living props; she, meanwhile, likes to pretend that they're not real but only a figment of her imagination. They're ever present in her videos and performances -- swabbing the deck aboard the pirate ship, squatting gangsta style in a high school gym while pumping their butts up and down, simpering behind fluttering hands or bowing to Stefani. That's right, bowing. Not even from the waist, but on the ground in a "we're not worthy, we're not worthy" pose. She's taken Tokyo hipsters, sucked them dry of all their street cred, and turned them into China dolls.

Real harajuku girls are just the funky dressers who hang out in the Japanese shopping district of Harajuku. To the uninitiated, harajuku style can look like what might happen if a 5-year-old girl jacked up on liquor and goofballs decided to become a stylist. Layering is important, as is the mix of seemingly disparate styles and colors. Vintage couture can be mixed with traditional Japanese costumes, thrift-store classics, Lolita-esque flourishes and cyber-punk accessories. In a culture where the dreaded "salary man/woman" office worker is a fate to be avoided for this never-wanna-grow-up generation, harajuku style can look as radical as punk rockers first looked on London's King Road or how pale-faced Goths silently sweating in their widows weeds look in cheerful sunny suburbs.

Stefani has taken the idea of Japanese street fashion and turned these women into modern-day geisha, contractually obligated to speak only Japanese in public, even though it's rumored they're just plain old Americans and their English is just fine. She's even named them "Love," "Angel," "Music" and "Baby" after her album and new clothing line l.a.m.b. (perhaps a mutton-themed restaurant will follow). The renaming of four adults led one poster on a message board to muse, "I didn't think it was legal to own human pets. But I guess so if you have the money for it."

Stefani fawns over harajuku style in her lyrics, but her appropriation of this subculture makes about as much sense as the Gap selling Anarchy T-shirts; she's swallowed a subversive youth culture in Japan and barfed up another image of submissive giggling Asian women. While aping a style that's suppose to be about individuality and personal expression, Stefani ends up being the only one who stands out.

It's not only Stefani whose big kiss to the East ends up feeling more like a big Pacific Rim job. Author Peter Carey's own recent foray into Japanophila, the book "Wrong About Japan," was a semi-autobiographical account of one clueless father's attempt to bond with his son over manga on a trip to Japan, and his futile attempts to understand Japanese culture through a Western filter. Why devote an entire book to being "Wrong About Japan," when you can just send out a one-page fax that reads, "They Are Inscrutable." Even some of the movies that consciously play with Japanese stereotypes can seem puerile no matter how fast the postmodern hipster spin, whether it's Lucy Liu's blood-lusting geisha in "Kill Bill," or Devon Aoki's killer Miho in the new "Sin City," who slays a multitude but is never allowed to utter a single word.

In the same New York Times magazine story that featured Murakami on the cover, the Dutch photographer Hellen van Meene was commissioned to photograph portraits of prepubescent girls and teens. The girls all look limp and innocent. Big, fat, unsmiling red lips like two slabs of raw ahi positioned on baby faces. It has that creepy porn feeling that I suppose is meant to reflect the Japanese predilection for "kawaii," or cute, and the sexualized image of schoolgirls. But this is not the way these girls really are. The accompanying text says that "while [van Meene] does not exactly 'stage' her subjects, neither does she try to capture their true, underlying personality or state of mind. Instead, she chooses to see her subjects as the raw material of her own fictions." Van Meene elaborates, "This is not just you now. This is a sense of you, created by me." Well, at least she's honest.

Shares