"I don't think you should get married at this point."

Dr. Phil is rolling out his straight-talkin' daddy routine on his eponymous TV show for a teary young redhead who's obsessed with losing weight before her wedding day. While the enthralled studio audience holds its breath, Dr. Phil is wide-eyed and earnest about the potential this problem has to mess with the young woman's marriage. The camera zooms in as the woman sniffles and nods solemnly, clearly upset but already committed to doing whatever Dr. Phil thinks is best for her.

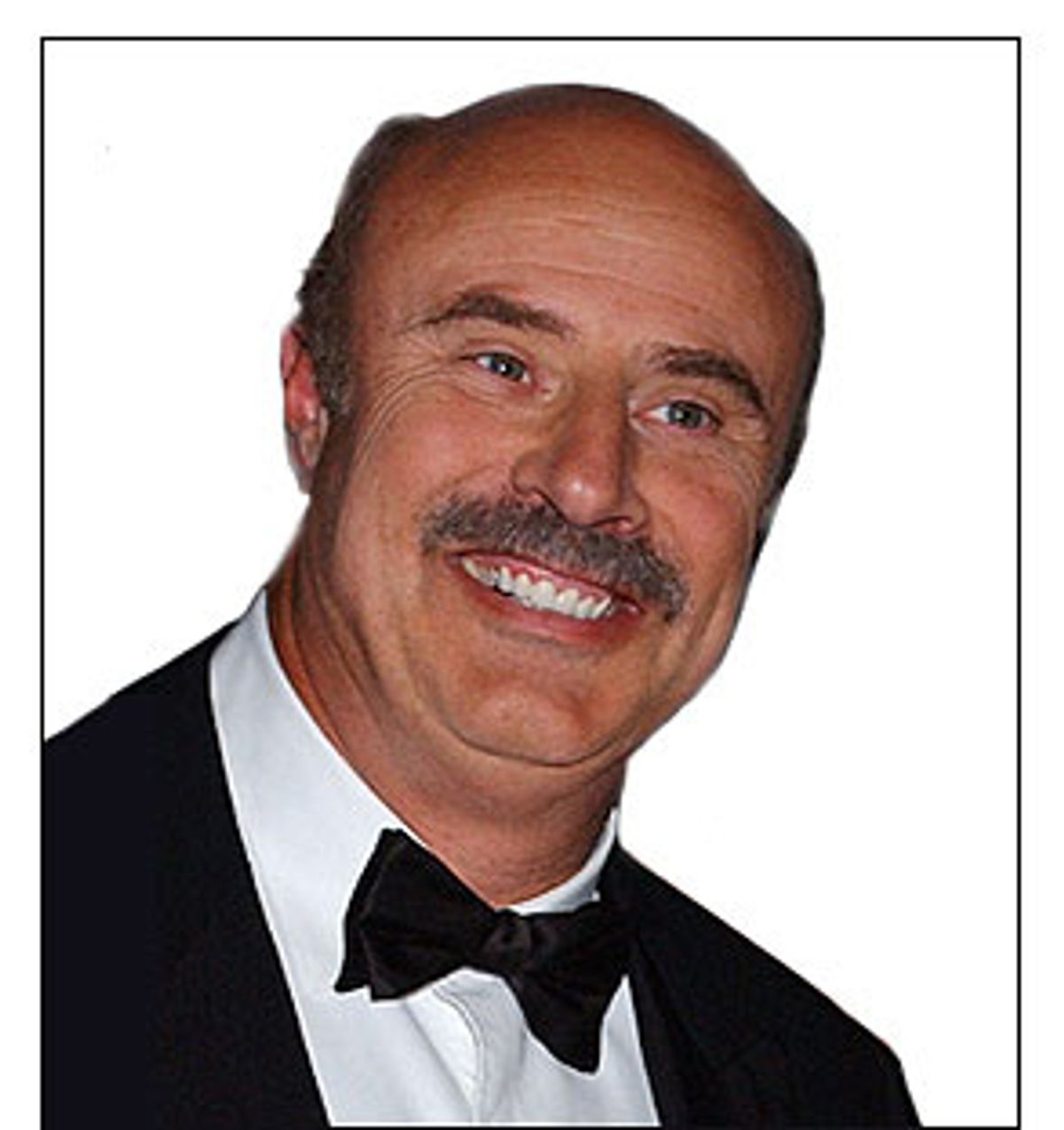

She's not the only one. Since his show hit the air last fall, Dr. Phil McGraw has become a father figure to a country hurting for a male role model. His comforting but directive style has a hold on America -- he's second only to Oprah in ratings, and boasts a steady flow of bestselling books, the latest of which, "Ultimate Weight Solution: The 7 Keys to Weight Loss Freedom," is a New York Times bestseller with 2.5 million copies in print.

But the very qualities that make Dr. Phil an appealing, trustworthy authority figure -- his unrelenting self-confidence and poise, his aggressive tactics, his irreproachable attitude -- appear to be the same traits that have created trouble for him in the past and that continue to plague him today, even as his popularity increases exponentially. In just the past month, McGraw has come under criticism for marketing nutritional supplements bearing his likeness, and was hit with a lawsuit filed last week from a guest on his show who claims his staff confined her in an apartment against her will, which led to a tragic -- and bizarre -- injury. Meanwhile, a new unauthorized biography, "The Making of Dr. Phil: The Straight-Talking True Story of Everyone's Favorite Therapist" chronicles many of the foibles and missteps of McGraw's past, from his alleged inappropriate relationship with a female therapy client to several ethically questionable business decisions. While plenty of unconventional public figures are criticized unduly for wandering off the most socially acceptable path, McGraw's alleged slips are a little more serious than he'd have us believe, and seem to fit a pattern of controlling, arrogant behavior.

McGraw's decision to endorse "Shape Up" nutritional supplements under a licensing agreement with CSA Nutraceuticals, for one, has taken many observers by surprise. Vitamin packs, drinks and nutritional bars that bear Dr. Phil's likeness have been stocked by major retailers since this summer, a cross-branding move that some have criticized as opportunistic and inappropriate. Predictably, McGraw is steadfastly unapologetic on the subject. While he reports that he discussed his decision with his mentor, Oprah Winfrey (who has consistently refused to endorse products herself) he remains determined to chart his own course. He has humbly given Oprah credit, as he so often does, telling the New York Times that he's learned "a tremendous amount" from her. But his decisions are his own. "I don't substitute anybody else's judgment for my own. Oprah has her plan and strategy, and I have my plan and strategy."

Late last week, the plot thickened as a bizarre lawsuit was filed against Dr. Phil, Paramount and staffers on his show. Convicted murderer Laurie "Bambi" Bembenek alleges in the suit that she was held against her will in a Marina Del Rey apartment by "Dr. Phil" staffers while awaiting the results of a DNA test, which she hoped would prove her innocence in the 1982 murder of her husband's ex-wife, and that were to be revealed on the show. According to the suit, Bembenek experienced a panic attack due to memories of her former incarceration, and attempted to escape through a window of the apartment by tying bed sheets together. The sheets came undone as Bembenek descended and she fell, injuring herself so badly that, eventually, her leg had to be amputated below the knee.

While the decision to tie bed sheets together and escape implies that Bembenek has all of the stability and capacity for rational thought of a Brady kid, strangely enough, she's no stranger to harrowing getaways. In 1990, she successfully escaped from prison after serving eight years for murder. After her escape, she reached a deal with prosecutors that allowed her to plead no contest to second-degree murder.

Whether she'll have as much luck in her current legal wranglings is less certain; representatives of "The Dr. Phil Show" insist that Bembenek was free to leave the entire time. Still, the confrontational tactics employed by Dr. Phil and his producers are plain enough to anyone who watches the show. Such methods are sure to be called into question, particularly in handling emotionally fragile guests. This suit may not go far, but if incriminating details emerge, McGraw still could find himself in a difficult spot.

By now, he's certainly used to it. "The Making of Dr. Phil," a biography by Sophia Dembling and Lisa Gutierrez, outlines some of the dark periods of McGraw's history, many of which have been explored in detail elsewhere. The book has that slightly unsavory, salacious tone that's common among unauthorized biographies, offering predictable criticisms from everyone from former business partners to former acquaintances willing to cast aspersions on McGraw's character. Unfortunately, the episodes in McGraw's life that have been called into question the most are reviewed but without providing much new information. While the book presents a worthy enough summary of McGraw's experiences and missteps, for anyone who's read two or three articles about the man before, there aren't many new details or scoops here.

Instead, the authors work with the stories they have, layer on as many damning remarks as they can, then quote liberally from McGraw's show or books in order to set him up as a hypocrite. When McGraw's first wife alleges that he cheated on her and demeaned her, then froze her out emotionally, instead of letting such harsh criticism stand on its own, the authors quote McGraw stating that marriage takes "a willing spirit" and a "long-term effort," as if every psychologist and self-help guru under the sun hasn't been married more than once.

But as inconsequential as McGraw's behavior at age 23 should be to any flawed human being with a checkered past, many of McGraw's reported mistakes, like selling expensive lifetime memberships to an unfinished health club that soon went bankrupt, aren't exactly minor blunders, and contribute to a picture of a man whose behavior appears to range from insensitive to unethical.

The most notable of the complaints outlined in the book and in investigative articles predating it come from a former therapy client of McGraw's who claims that he carried on a controlling and sometimes sexually inappropriate relationship with her. The client was 19 years old at the time, and alleges that McGraw touched her inappropriately, insisted that she check in with him often, and kept her "totally dependent" on him. She eventually filed a complaint with the Texas State Board of Examiners of Psychologists. Although McGraw settled with the board, disciplinary actions taken by the board were quite firm, including, according to "The Making of Dr. Phil," "a public letter of reprimand, a year of supervision by a licensed psychologist, complete physical and psychological exams, and an ethics class." A year after the official reprimand was issued in 1988, McGraw closed his private practice and entered into the business of trial consulting, where he fortuitously consulted Oprah Winfrey when she was defending herself against libel charges from Texas cattlemen. Although McGraw downplays the incident with the 19-year-old patient, claiming that it was "investigated and dismissed" and that he was fed up with his work as a therapist anyway, the timing of his career change is impossible to ignore.

In addition, a former business partner of McGraw's, Thelma Box, alleges that McGraw sold his stake in their self-help seminar company, Pathways, to a third party a full year before he let her know about it. Box claims that she co-created and coauthored the materials used in the Pathways seminars, traces of which are found in Dr. Phil's approaches and strategies on his show, but that no credit or mention of her name is offered, either by McGraw or by the associates who eventually purchased her share of the company. Unlike some of the other sour-grapes critics in the book and in other pieces, Box seems a reliable character witness. She compliments McGraw and says she gained a lot from working with him, and she appears to report the facts of her history with him without going out of her way to attack him. Mostly, she's alarmed that, despite her influence on his work, he's never mentioned her name in his books, on his show or in interviews about his background.

Taken alone, such criticisms might ring hollow. After all, a man with McGraw's obvious talents and charisma should hardly have to march around, reciting a list of credits. And generally, when the usual complaints about abusive or egocentric behavior are lobbed, as they have been at McGraw by former associates and employees of his show, it's not difficult to write them off, since McGraw's strong personality is a big part of what makes him a natural leader. The man is a polished brand in motion, a remarkable presence onstage with a likable, self-assured manner, a quick wit, a knack for giving straightforward, sure-footed advice, and an uncanny ability to address criticism before it appears.

"I don't expect you're going to substitute my judgment for your own," he tells the young woman who's just put her wedding on hold. "Y'all are gonna decide what you want to do."

McGraw will often stop at the end of a guest's spot, or at the end of a show, and address the audience. "We're not doing 8-minute cures here," he tells viewers, over and over again. All he's offering, he insists, is "a wake-up call" or "an emotional compass."

Still, on show after show, it's clear that Dr. Phil eclipses the boundaries of the innocuous role he claims to fill. It seems as though he can't stop himself from getting far more involved and magisterial than would be recommended by most licensed therapists.

On one show, a teenaged son is tricked into appearing under false pretenses, and is then confronted and threatened with a total withdrawal of support and protection from incarceration if he doesn't enter rehab on the spot. Such interventions may be necessary for those with drug problems, but surely taking such avenues on national television should be considered cruel and unusual punishment for a teenager, who's apt to be consumed by appearances. Indeed, the boy seems mortified by the situation and appalled that his parents have lied to him.

But drug users aren't to be taken seriously, you see, and with every legitimate expression of anger and betrayal that comes out of the kid's mouth, we're reminded that "it's the drugs talking." The kid eventually storms backstage, where there are more cameras, of course, and in a "private" conversation, Dr. Phil insists that he decide whether to go straight to rehab, or face the consequences. The kid angrily chooses rehab, and he and his parents fly directly from the show to the facility, escorted by a bodyguard -- apparently the boy doesn't have the option to change his mind once the cameras aren't rolling.

Whether Dr. Phil has just saved the kid's life or shamed him in front of millions of viewers goes unchallenged -- by both the audience and the kid's family. Instead, they all stand around, wide-eyed and obedient, waiting to see what the good doctor will prescribe next.

This "Surrendered Family" phenomenon is most evident on the episodes of the show surrounding the "Dr . Phil Family," a couple and their two daughters who have chosen to subject their lives to around-the-clock scrutiny by the show. Dr. Phil's immersion in their lives is complete, from the use of around-the-clock video cameras to the involvement of therapists and lawyers to the family's regular appearances on the show. They have completely yielded their lives to Dr. Phil's tough love machine, and on each "Dr. Phil Family" episode, their problems, which range from infidelity to teenage pregnancy, are dragged out and dissected. Naturally, their ongoing struggles make for some seriously entertaining television. These episodes constitute a mini Dr. Phil-branded reality show, featuring all of the denial and outbursts and insults you'd expect from members of a wildly dysfunctional family. While the advice Dr. Phil offers is consistently sound and reasonable, and may indeed offer hope to other families in crisis, his role as the ultimate authority is hard to ignore. Alexandra, the 15-year-old daughter who has just decided to raise her child on her own, is shown talking to the baby's father on the phone.

"Dr. Phil actually thinks it's best that you and your family don't visit the baby until you actually speak to him," she tells the boy. Alexandra and her family hint that the baby's father and his family are trashy, irresponsible people, but you can't help but admire the class they demonstrate in refusing to throw their lives into the ravenous Dr. Phil wood chipper.

The irony, of course, is that the very behavior that allegedly led to McGraw's receiving a public letter of reprimand is exactly what makes him "America's Favorite Therapist" today. It's his aggressive, confrontational approach that appeals so much to a nation that's lost its faith in the talking cure. While traditional therapists often encourage a client to discuss their feelings in an uncensored, unlimited way, for Dr. Phil, feelings are merely a brief rest stop on the way to committing to life-altering behavioral changes. This is a macho approach to therapy, couched in the tough-love language of football coaches and wood shop instructors.

"That dog won't hunt!" Dr. Phil blurts at guests like an impatient daddy, giving them firm instructions on how to stop messing up their lives, while disparaging softer approaches. "Trust me, I'm not going to spout a bunch of 'guru-ized' stuff about thoughts and emotions, or tell you to go up on a mountaintop and get in touch with your 'inner child,'" he writes in his bestselling diet book. "You can either sit around and stew about the situation, or you can make the choice to be self-directed, take action, and adopt a solution-side approach to your life."

Although that solution-side approach -- exercise, don't eat when you're emotional, control your portion sizes -- is far less groundbreaking than it sounds after it's been spiked with down-home Dr. Phil flavor and marketed by the Dr. Phil juggernaut, his fans don't seem to care. They're anxious to have him weigh in on one more aspect of their lives that feels out of their control.

In fact, it's difficult to imagine devoted disciples of Dr. Phil changing their minds about him for any reason at all, since the nature of his authoritative, instructive relationship with his guests, viewers and readers protects him from scrutiny. Just as taking your football coach's advice is predicated on turning a blind eye to the fact that he's sort of an abusive jerk, so does accepting Dr. Phil's word as the gospel mandate that all criticisms of him are ignored, or treated with utter skepticism. Viewers can take the cue from Dr. Phil himself on this front. As he recently told the New York Times, "I guarantee you there is absolutely nothing -- nothing I could do that somebody wouldn't have a problem with. If I was on the air and was just kind of a plain-vanilla personality that took the safe road and the safe way trying to please all of the people all of the time, I'd been gone in two weeks."

The message is clear. Part of being empowered, of "getting it," of "telling it like it is," of being a tough guy and a winner instead of a whiny little loser, is wrapped up in ignoring the criticisms and complaints of others. Thus, no matter how many times Dr. Phil's ego and overbearing tactics bring him negative attention, it's clear that his devoted viewers will continue to see him as comforting and decisive father figure in their lives. And what could be more American, really, than a macho, charismatic leader who blunders arrogantly into disastrous territory, while a nation of obedient children looks on?

Shares