For much of his improbable career as a filmmaker, James Toback has suffered the slings and arrows of his own outrageousness. Entering the American movie scene first as a screenwriter (for Karel Reisz's 1974 "The Gambler") and then as a writer-director (with the 1978 urban nightmare "Fingers"), Toback was an unruly provocateur at a time when the Hollywood spectrum was constricting into popcorn mythology at one end and yuppie soap opera at the other.

The merging of his personal life and his creative obsessions with sex and gambling made him a target of Spy magazine, which detailed his dating methodology with great merriment. Journalists have always had difficulty dealing with the outsize appetites of expansive theatrical personalities; both gossip columnists and upscale pundits love to wax holier than them.

Combined with all the bad P.R., early career flops like the inchoate "Love and Money" (1982) and the charming, underrated "The Pick-up Artist" (1987) would have sunk less hardy spirits. But with the help of friends like Warren Beatty and Barry Levinson, Toback kept pulling himself back into the movie game. His scintillating 1990 documentary about the meaning of life, "The Big Bang," followed quickly by his droll, Oscar-nominated 1991 script for Beatty's and Levinson's "Bugsy," opened new accounts in the bank of critical goodwill.

By the time he made "Two Girls and a Guy," a sexual psychodrama with Robert Downey Jr., Heather Graham and Natasha Gregson Wagner, hipsters and independents had caught up with him. It was one of the best-reviewed films of the '90s -- though, to my mind, it was flaccid work and the rare Toback film to be overrated.

My sense that he'd arrived was confirmed when Steven Soderbergh referred to Toback's movies with insight in the 1999 book "Getting Away With It." In a diary section, Soderbergh writes, "Here I sit like a character in a James Toback movie, having promised something I can't hope to deliver and, on top of it, feeling completely bankrupt in an artistic sense. I've put myself in this situation, so what am I seeking from this? Do I want to fail and be disgraced?"

Soderbergh sees the Toback persona as an all-or-nothing aesthetic gambler. Which brings us to Toback's comeback in that vein, "Black and White," a semi-improvised piece of documentary fiction that has the heat and deftness of Norman Mailer's journalism or John Dos Passos' "U.S.A." At its core it depicts the intersection of upper-middle-class, hip-hop-besotted white youths with street blacks yearning to sell their mystique for a slice of white America's pie. It's also an inflammatory, millennial vision of lives lived without boundaries, for better and worse. It's a group portrait of Our City, USA, with guns, basketball, bimbos and bribes.

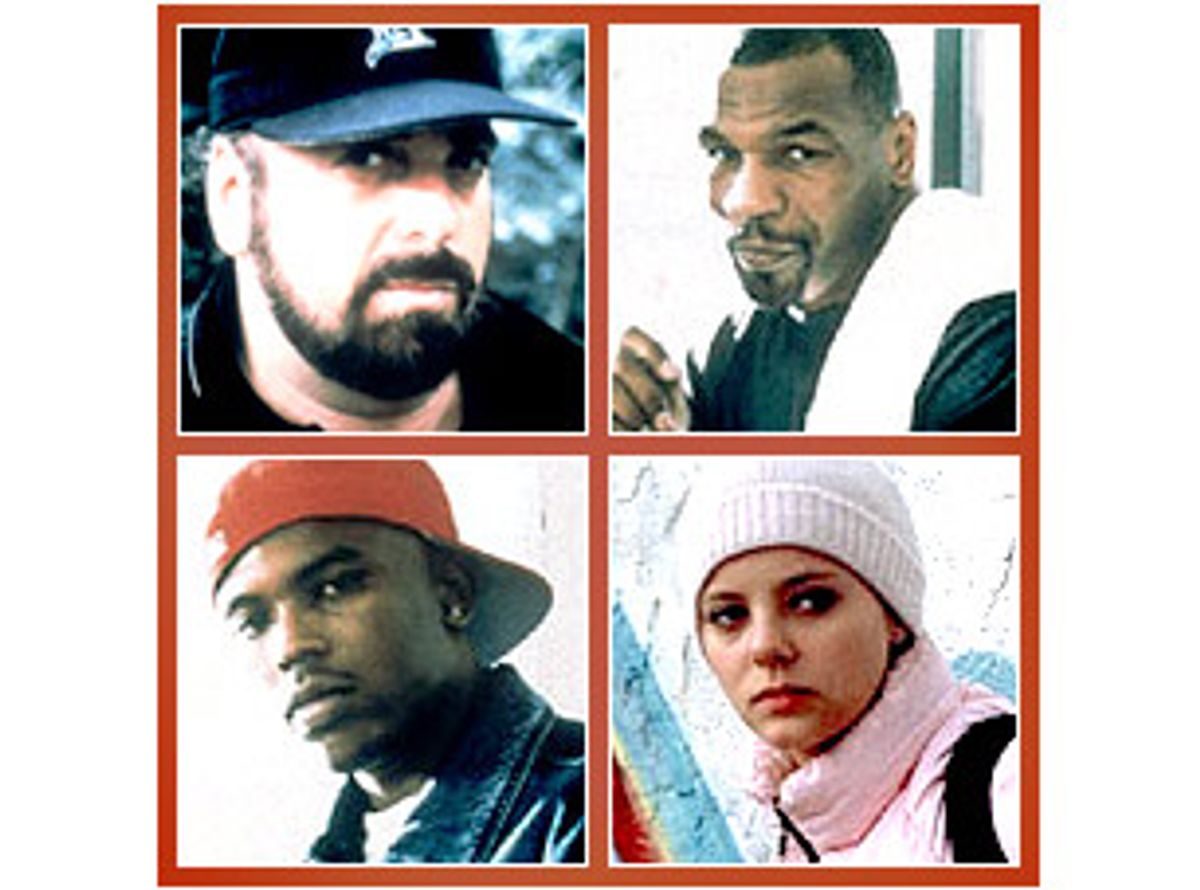

The pivot of the film is Bijou Phillips (John Phillips' daughter), a preppy blond beauty who erotically flaunts her way into the circle of Power -- that is, the Wu-Tang Clan member who goes by the name of Power, playing a rapper who wants to leave his back-alley ways behind and become a bona fide pop-culture success. Toback surrounds them with a panoply of figures who are equally confused and compromised, ranging from a black basketball player (Allan Houston) and his white Ph.D.-bound girlfriend (Claudia Schiffer) to a conniving undercover cop (Ben Stiller) and an ambitious D.A. (Joe Pantoliano) whose sons are also in thrall to hip-hop. Add Brooke Shields as a documentary filmmaker, Downey as her gay husband, Marla Maples as Phillips' mom and Mike Tyson as himself, and you've got a society that's suffering, collectively, from exploding possibilities and imploding personal identities.

Toback plays a bit part as a recording-studio owner who will deal with Power only through a lawyer. But the film's echt Toback character is Stiller, a guy who can't help going for what he wants even if it results in murder by proxy.

Advance publicity has predictably focused on Leonardo DiCaprio's tangential relationship to the movie: Toback was doing the New York club scene with the young actor when he was struck by the influence of hip-hop on the star and his friends. But his fascination with black urban culture goes back decades, to earlier New York hip scenes and to his close friendship with Jim Brown.

Toback says that as a teenager he was living the life of "the White Negro"

even before he read the famous Dissent essay in which his old friend Norman

Mailer named and analyzed the phenomenon. Indeed, rereading Mailer's essay after seeing Toback's movie, which also portrays psychopathy as a mode of existential exploration, you may feel that the biggest difference between "White Negroes" and today's "wiggers" is that what once was cutting-edge behavior is now (in urban society, at least) perilously common.

I've read that "Black and White" derives from your experiences a few years ago clubbing around with Leonardo DiCaprio. But the subject matter of this movie is not that new for you.

The real origins are much deeper. They go back to the sons of the woman who worked in our apartment when I was growing up. Thomas and Eugene were my age -- we're talking about when I was 3, 4, 5 years old -- and I was keenly aware of them being a completely different kind of person because of race. I was definitely drawn to them. I think I ended up doing something physically violent to one of them, but it was out of a competitive friendliness. Then there was a guy named Gus Chappell in third grade, who I became very close to. [He was] the only black guy in school -- the Ethical Culture school, a purely white, liberal, upper-middle-class, largely Jewish private school in New York, which puts you in a world at once broad-minded and narrow in its social exposure.

The real turning point came when I met and fell under the spell of Carl Lee. When I was 15 or 16 I saw Shirley Clarke's "The Cool World" [the 1963 urban underground classic] and was magnetized by Carl Lee. I went back to 72nd Street, where I lived, and down the block, there, two hours after seeing him play the lead on screen, was Carl Lee standing in front of his white Triumph TR6, smoking a cigarette in his navy-blue blazer and his white shirt, looking very debonair. I told him I'd just seen the movie and that he was great. He was effusively friendly, and by the end of the conversation I had lent him $20 and bought some marijuana for him.

In the sort of hip world of New York, Carl Lee was the hip-black-actor icon. He was for hip people what Sidney Poitier was for mainstream people. He was the star of two of Shirley Clarke's films, he was the off-camera influence to her "Portrait of Jason," he did a legendary "Othello" at Stratford, Conn., and he was the son of Canada Lee, who had been one of the most famous black actors of the '30s and '40s. He had a huge effect on everyone who knew him.

Shirley Clarke's whole life revolved around Carl Lee; they had this on-and-off 30-year relationship and she totally supported him the whole time. His influence was a combination of language, style, personality and psychology. He was a great analyzer of human beings, particularly in their sexual and racial nature; he was a philosopher of sex and murder, talked about these subjects endlessly and always lived some kind of criminal life on the side. He had a magnificent baritone voice. He could sing, but he was an electric, hypnotic, evangelical speaker. He spoke in the rhythms of a great preacher, but his subject was casual sexual analysis, race, murder, crime, death and madness. He spoke beautifully and broadly and powerfully, with great emphasis, and looked you right in the eye. He would not have been capable of an ebonic moment.

The attraction was definitely physical, and stylistic and psychological. Did you ever read that strange little piece on Alain Delon I did in Projections 41/2? [Projections is a quality-paperback magazine devoted to filmmakers writing or talking about filmmaking.] In my first sentence I say, "I am not to my knowledge a homosexual." That would be the appropriate phrase to describe my response to Carl Lee.

It became a very unusual, interesting friendship, which lasted really until he died, which was the day he did his looping on [Toback's 1983 movie] "Exposed." He came to the studio to do his lines, and was clearly in the throes of one of his more intense and defeating heroin periods. He said that he desperately needed $50, which I gave him. He died of an overdose an hour later.

He had introduced me, indirectly and directly, to a whole world that I didn't know at all before. Among other things, it was a world of interracial sex. The life I led between the time I met him and the time that I met Jim Brown a decade later was affected more by him than anyone else.

Was Mailer's "White Negro" a big influence on you in this period?

It was a philosophical articulation of what I was already experiencing -- in the same way that reading Dostoevski's novella "The Gambler" didn't turn me into a compulsive gambler, but was an explanation to me of what was already going on. And reading Mailer, it wasn't just "The White Negro" -- it was reading [Mailer's 1965 book] "An American Dream," which had a character vaguely based on Miles Davis who might as well have been Carl Lee. In fact, two of the people I met through Carl were Miles Davis and Richard Pryor. Miles idolized Carl, rather than the other way around. Pryor was just getting started. The first night I met Pryor, Carl and Miles Davis and I were having dinner together and Carl was saying, "You've got to see this guy, he's unbelievable; he does this routine where he's a fetus and you follow the whole fetal development." And that was Richard Pryor, either at the Bitter End or the Village Vanguard, one of those clubs in the Village.

I met Jim Brown 10 years after I met Carl Lee, and he had a similar effect. I entered his world even more completely. But by the time I moved into Jim's house, I had a far more established identity of my own. I had much more confidence in myself. I had been through quite a bit more independently, both in the way I lived as an undergrad at Harvard [he graduated in 1966] and also in my marriage to a girl who was the granddaughter of [the] Duke of Marlborough. I had a lot of serious and rather jeopardizing gambling relationships and experiences.

So I certainly was coming to Jim Brown's house with a lot more sense of a developed self. Clearly not enough to pack it in and call it a day, or I wouldn't have been there in the first place. I still felt myself ready to experience a new world. Barry Levinson told me that when he saw "Black and White," it made him feel like he'd paid a fascinating visit to a foreign country. And that's how I felt when I entered Jim Brown's house. I was sufficiently intrigued and excited by it that I didn't want to leave -- and I didn't. I just stayed and stayed and stayed. Part of what was going on was just that I was learning a great deal in a lot of ways from Jim himself, which I tried to get at in my book ["Jim," Toback's admittedly self-centered portrait of Brown]. The rest of it was the world itself.

And that was different from the hip, cultured world of Carl Lee. It was a precursor to the superstar world that became the norm for black celebrities, or at least how they would be perceived.

That's right. It was the first time that black figures in sports, music and movies were really moving to the center of American life and were being allowed to engage in their freewheeling interracial sexual behavior without a lot of condemnation, not only from the white culture at large but from their own black community. I remember Rafer Johnson's affair with Gloria Steinem had a huge impact symbolically.

The paradox of "Black and White" is that while most adults will experience it as entering a foreign land, you leave thinking that everyone's kids are living in it -- and just not talking about it with their parents. With Carl Lee, you were in the avant-garde; with Jim Brown you were with a popular trailblazer. In this movie, though, you're talking about something incredibly widespread -- and, considering how widespread it is, little commented on.

Completely. That's one of the key distinctions between the White Negro and the whole hip-hop phenomenon happening today. Then, to be a white person crossing over, you were abandoning something that was a part of the central culture. You were at odds with it; you were ostracized from it. Now, if you're young and white and cross over to the black side, all you're doing is participating in what the white mainstream culture is. Unless you're talking about skinheads, you're not abandoning anybody. You're in effect straddling both sides, which is why Bijou Phillips says in the movie, "I can do whatever I want. I'm young in America." What she's really saying is, "I'm white in America and I can do what I want. I can go there and come back and be in both places at the same time."

And that's something not open to a black girl of her age.

No. Which is why the reverse exploitation -- well, exploitation may be too strong a word -- but the reverse use of white culture from the black point of view is economic. As Power says, "I want to get some of her information." He refers to it, metaphorically, as "Central Park West living." He asks, "What is it that white people want from us? I guess it's a life force or something."

The irony is, the real thing in hip-hop that's going on is: Let's participate in ownership, let's become businessmen. There's an anti-revolutionary, capitalist-grounded nature to the black side of hip-hop. There's a desire to be rich and famous, not to rip apart society. The Rap Brown era is of the past, which is why it was so bizarrely anomalous to see the picture of him in the news the other day. Rap Brown got arrested in Atlanta for murder; it turns out he's this kind of big drug dealer in Atlanta. I mean, last I heard he was doing cookbooks in New Haven, and here he is arrested for killing somebody. The irony is that all these Black Panthers from the '60s became drug dealers in the '90s and involved in traditional black street crime.

How did you get all these people to work for you on "Black and White"?

I felt like fucking smacking Tim Robbins the other night. I saw him on television, and he was saying, "On 'Cradle Will Rock,' I got all these people to work for nothing -- so and so got $1 million, so and so got $500,000." I mean, I got everyone to work for $2,000! They just wanted to make this movie.

When you compare it to other movies about race, yours never becomes schematic -- you know, whites do this, blacks do that.

What saved me was the choice to have a strict, developed narrative. I felt this movie can indulge in all of its riches of surprise only if it has a really tight, interesting plot that it gets into not too late -- and I think I get into it just at the last possible point in the movie. Once you get into it, it drives you. Whatever else is going on, the film does have this "What's going to happen next?" sense to it. As I was editing it, the movie started to work better and better as the narrative drove it more and more.

That's interesting because the critical rap on you always seems to be: He's brave, he's audacious, but he also has this clumsy melodrama. I often respond more to your movies when they do have a melodramatic hook.

You read the newspaper any day and you see melodrama that puts half of this to shame. I remember William Inge [the author of "Picnic" and "Splendor in the Grass"] talking about how he only read tabloids because they made him understand that the world he was depicting, which he knew was real, was no more sensational or unrealistic or melodramatic than reality. Melodrama is half the narrative power of most great literature -- all of Dostoevski and Shakespeare is melodramatic, but the same people who condemn "Black and White" as melodrama would never refer to the melodrama of "Macbeth."

The melodrama hinges on the cop played by Ben Stiller; I know a lot of people find him problematic, but I think he's terrific. He assumes the burden of it being a tale of people testing the bounds of their behavior. I saw a lot of vintage Toback in him: his willingness to do things that may be bad, but then agonizing over it in a way that becomes its own weird masochistic reward.

Michael Barker, of Sony Classics, came up to me at Telluride and said, "The Ben Stiller character is the most purely Tobackian character you've ever written. You can't tell me the whole movie was improvised; there's no way Ben Stiller came up with that dialogue." "You're right," I said, "it's all written." Some people think Ben Stiller's terrific in the movie, and others think he's the worst thing in it. Almost everyone loves Tyson and Downey in the movie. Just about every other character is all over the place. Did you see Stanley Crouch's piece in "Talk"? His favorite character is Claudia Schiffer. Different people react in different ways. I keep saying, over and over, that more than any other movie I know of in the last 10 or 20 years, this movie is a real Rorschach test for the viewer on a number of incendiary issues: race, sex, interracial sex, murder, respect for the law, young kids and their behavior, identity, class distinctions, music. It's almost impossible to see the movie and not reveal how you feel in some fundamental way about these things -- as opposed to a lot of movies which you might enjoy, and say it's a good movie or a great movie, and yet you're revealing nothing about yourself except your taste in movies.

If early on you decided to give the film a melodramatic spine, was Stiller the first character you came up with?

The first character was the D.A.'s son. I knew there had to be a murder, because I don't think you can make a movie about hip-hop without having there be a murder, since it happens to be one of the distinctive forms of that existence. The question then would be to try to hook into that story one of the white kids obsessed with the black life, as the one who's enlisted to do the murder. And I thought if he's the son of a D.A., that's really interesting. So those characters came in, and then Stiller's character came in as a decoration on that theme. But first there were white kids into hip-hop -- hip-hop means murder, who commits the central murder and why, and then what are the consequences of that murder. If you answer those questions the movie is basically set up.

You've said you wrote Stiller's character totally. How much was improvised?

A lot. All the Wu-Tang stuff [Raekwon and Method Man as well as Power], all the Mike Tyson stuff and all of Downey's and Brooke's stuff. They all had goals and intentions in their scenes but did not have their dialogue written for them. They were able to create their specifics in speech and behavior given that they knew where they were going. In all the scenes with Allan Houston, Claudia Schiffer, Ben Stiller and Joe Pantoliano, every word was written. So it was a combination of improvisation in terms of language, on the one hand, with total tight scripting on the other. And I think it would be hard for people watching this to tell the difference.

In your improvisational mode, who was giving out the goals?

I would give the actors the goals, and in the case of the Wu-Tang Clan guys, they would often correct my goals, or correct my methods.

Can you give me an example?

When they come into the new club, and tell the white team opening it up that it's not going to open up unless they're cut in, I originally had it in a much calmer, more verbally oriented way -- that it was extortion through subtle threat. And Power said, "Fuck that shit! What do you mean, subtle threat? We just walk in and stick a gun in their face. We'd just say this is what you're going to do, here. Who the fuck are they? And that's going to be the attitude. Who the fuck are you?"

The minute he said that, the whole tone of that scene became completely different from the way I had imagined it. And I didn't even tell the white kids in the scene that that's what he was going to do. All through the first few takes, they were shaken up by it. Because even though they were real club kids and do set up clubs in New York that way -- they round up models and the right people for premieres and get the style of a club going -- they're not used to having a bunch of guys come in and stick guns in their faces and extort them. Particularly the way it was done, which was without warning. I had told them it was going to be totally different, it was going to be a discussion. They thought they could reason, they could argue. And all of a sudden on the first take they are hit with something completely different.

Bijou Phillips -- you never knew what the fuck she would say or do next. There is no line between her unconscious and her articulation of it and her behavior. She is a genuine psychopath. I say that with affection and admiration, because she's also incredibly smart and talented, so she knows how to amuse and how to get and hold attention. If she were just a psychopath, you wouldn't want to use her; you'd just be bored. But she is always kind of amusing and interesting, and if one thing isn't working she has a good sense of it, and she just starts on something else.

What about your own appearance in the film? You play a fellow who owns a recording studio and is fearful of dealing with Power.

I knew I needed a character like that. And it's much easier for me, if I'm going to have a guy who I want to make fun of a little bit, to do that myself than to try to find some interesting and articulate actor who's really ready to do it and go all the way with it. Most actors, when you only give them a scene or two and they know you're going to ridicule them, they really don't like it. They cheat it a little, they try to cut a corner or two and make the character a little more appealing and likable. I know I don't give a fuck, so if I think I can say the lines and make the thing believable, I'd be better at getting my goal than anyone else immediately available. And he is a realistic character: He doesn't want a body in the elevator, a corpse in the lobby.

You bring up Crouch's "Talk" piece. He writes about the film as if it's a cautionary tale, and that's not how I experienced it. [Crouch writes: "Toback is hardly the first one to realize that the forces of the gutter, if sufficiently powerful, can beget terror, destruction, and moral chaos."]

That is how one is going to see it if one has his attitude toward this scene. Hip-hop is not being celebrated here. The movie doesn't take its side. It shows all the attendant behavior in a cold, detached way. So it's possible to adopt Crouch's perspective, even if you don't and I don't. I wanted the movie to evoke a complexity of response. You see it in the way that people respond to the murder, too. A lot of people say that this movie exposes the Wu-Tang guys as people who are ready to kill to get what they want, with no compunction about it, and that therefore they are morally reprehensible. Certainly, one attitude toward what they do is: "Murder is not the way to settle something." But the other is: "The victim was a snitch, the lowest of the low, and he should have been killed."

The movie does not gang up on you if you want to take either point of view. It doesn't advocate both, and it doesn't exclude either. When I had central surrogate characters for me, in "The Gambler" and "Exposed" and "The Pick-up Artist," it was harder for me to want to be totally detached. But by revolving this movie around all these people, I'm not saying any one person is the hero or the right one. I'm saying that this world is worth observing and listening to. So you can come down on one of several sides on almost any of the issues. The only thing you could not say is that this is a movie discouraging or condemning interracial sex. It is not possible to say it shows the odiousness of interracial sexual behavior.

You and Beatty again. Wasn't that his line from "Bulworth"? "We should keep fucking each other till we're all the same color"?

I claim he got that from me! He claims he came up with it. We had a very funny and not unserious argument about that. I said I can't believe you're going around telling people you wrote that line, when I wrote the line and I've been telling you for 10 years and it took me five years to convince you. And he said, "What?" I'm sure he believes what he's saying, but he's wrong.

When you talk about the divergent attitudes toward the street culture in this movie, you're talking about genuine ambiguity, something that's been a part of our best adult pop culture. I wonder if there's a bias reflected in the general condemnation of Power? To its great credit, "The Sopranos" does not go soft on its characters either, but if it's Tony Soprano ordering an execution instead of Power, you're more likely to hear, "Well, the guy was a snitch."

"The Sopranos" is a good analogy, in that you're being allowed to accept the morality of the wise guys in the movie, while at the same time you're not being courted to accept them as you were in "The Godfather." You can enjoy "The Sopranos" and say this is a bunch of lowlife hoods. Week after week, you can say, I still want to see these characters, even though they're a bunch of fucking pigs. Not that you have to say that. But it's not like "The Godfather." You cannot go to "The Godfather" and say this is a bunch of fucking pigs. The movie romanticizes them, glamorizes them and insists you like them. And indeed, "Bugsy," too, did that. There was no way you could go with Bugsy Siegel and say he was a homicidal creep and he deserved to be shot in the end. If that's how you feel, you're not going to like the movie. It does, on some fundamental level, take his side, in a way that "Black and White" does not take the side of any of its people. All are adrift, in transition from one unrealized identity to another.

Is that why you cast all these people? Brooke Shields, Marla Maples, Mike Tyson, Robert Downey Jr. -- they definitely are in flux.

All of them. And that's one of the reasons they were so ready and eager to do the movie. It gave them an opportunity to display that and be observed in the process, Brooke in particular, as if the film and life were going on simultaneously. And Downey as well. Of course, he's in a class by himself. The sad thing is, among the most significant factors that have brought him from cute talent to real acting genius has been the massive unjust suffering inflicted on him. Some of it he's inflicted on himself, but the legal part has been inflicted on him. And that has worked to deepen him as an actor, to the point that he's as good as or better than anyone else around today.

The bit with him and Tyson is really interesting because you have two guys who are wild in different ways. Tyson is like a murderous boy. You're touched by him when he tries to deflect Downey's sexual come-on; then this other side comes out.

There is a really complex and fascinating portrait going on there -- also because of the mismatch of the body and the voice, and the face and the body. I love that line when Brooke pays him the modest compliment of saying he has beautiful eyes, and he immediately translates and exaggerates that into "No one ever expressed to me that I was gorgeous before." Even the way he uses "expressed" instead of "told" and uses words like "fastidious" -- that's part of his language; he'll suddenly stick in a multisyllabic word.

Very much like Bugsy, who learned a new word every day from Roget's thesaurus in real life and put it on his mirror in the morning when he was shaving. You get a linguistic flavor from that, and it's a hybrid. And who including me, who knows him, could have written "expressed" instead of "told," or "fastidious"? Those are words that come out of his yearning to complicate and expand his vocabulary, and who knows where they're going to pop up, and when. And they're not used inappropriately, in a Sam Goldwynesque way -- they're used in a fresh and surprising way.

Without giving too much away, I found Allan Houston moving and vulnerable as the basketball player and Schiffer truly chilling as the girlfriend who goes from him to a string of other striking black men. She's studying anthropology and she's treating him as a specimen.

She's a truly Nietzschean character -- the woman Nietzsche never knew and always dreamed about, who might have saved him from madness, prostitution, syphilis and an early death. She's the Nordic plunderer in a black world, Leni Riefenstahl among the Nubians. She will survive them all, including Mike Tyson.

Shares