Talk with filmmaker Barbara Kopple for just five minutes and you understand immediately how she makes the kinds of movies she does. In 1976 Kopple won an Academy Award for her first feature, "Harlan County, U.S.A.," a documentary detailing a bitter, drawn-out strike among Kentucky coal miners, a case of men and women taking a stand against big business even though doing so threatened not just the fabric of their community, but also their lives. Kopple won another Academy Award in 1991 with "American Dream," which chronicled a workers' strike at a Minnesota meatpacking plant. Since then, she has made a fiction feature (last year's "Havoc"), and her documentary subjects have included figures as disparate as Woody Allen and Mike Tyson.

Through 2005 and well into 2006, Kopple and her co-director, Cecilia Peck, followed the Dixie Chicks on tour and behind the scenes. The picture they've made, "Shut Up & Sing," which opens in New York and Los Angeles on Friday and in other cities beginning on Nov. 10, is without a doubt a political documentary, a picture in which the views of its subjects -- Natalie Maines, Martie Maguire and Emily Robison -- emerge not just in the things they say (beginning with Maines' now-famous anti-Bush comment, made in 2003) but in how they go about conducting their business, and their lives. Kopple's sensibility helps shape the picture, of course -- that's part of the job of a good documentarian. But watching "Shut Up & Sing," you're always aware that Kopple and Peck are painting a portrait for us, in brushstrokes of words, music and pictures, as opposed to telling us what to think. As a piece of political filmmaking, "Shut Up & Sing" pulls off the feat of being subtle and direct at once.

In conversation, Kopple's warmth and kindness come through immediately, as does a sense of self-effacing confidence. But it's also clear that Kopple isn't the sort who's given to finding only nice things to say about everyone. She seems to have a far more rare and more valuable gift: You get the sense she is blessed with the curiosity to find out what's really there in a person, and to figure out how that informs the story she's telling.

Salon spoke with Kopple, a youthful-looking 60, in New York, where she talked about why she thinks documentaries have captured the interest of the public in recent years, about the importance of avoiding cheap shots in documentary filmmaking, and about what she learned from the Dixie Chicks. (You can listen to a podcast of the interview here.)

The co-director of "Shut Up & Sing," Cecilia Peck, isn't here today. Can you tell me how you and she started working together?

Cecilia and I have known each other and been friends for 10 years. We met in Cannes; I was doing a documentary that someone had asked me to do, about the underworkings of the Cannes Film Festival. Cecilia was at that time [working as a writer], and the producers put her on the film not for the shooting part of it, but to help them coordinate things. It wasn't really a wonderful experience for any of us, doing this film, because the producers were a little strange. So it was difficult. But I met Cecilia, and that was incredible for me, and I think also for her.

She went back to Los Angeles, and I went back to New York. And I said to her, "I want to show you how wonderful documentaries can be. Would you ever consider coming to New York and working on some of the films I'm doing?" She said yes, and there she was.

In the meantime, her father, Gregory Peck, was doing a one-man show. And she said, "Nobody has ever filmed my dad." And I said, "OK, we'll all go out and do one show and give it to your folks as a gift." So we went to Boston and we filmed, and then we couldn't tear ourselves away from doing a film about the Peck family. A year later, we were still doing it. And that's what started us really working together. Our friendship got very close. And neither one of has an ego at all ... It's all about the story. We think a lot alike. And it just works.

And how did "Shut Up & Sing" come about?

We have a mutual friend, Cecilia and I, who knows the Dixie Chicks really well, and he would often talk about them. Even before they made the comment -- they were just starting out on their "Top of the World" tour -- we thought, Wow, wouldn't it be interesting to do a film on them? So we got in touch with them and said we would love to do a film. But they said, "No, we've just hired this Web-site crew, and they're going to travel with us."

Then they made the comment. And we were totally fired up: We could have been there! We could have been filming all this! So we wrote a proposal, and we hounded them. They just really had to come to terms with, Do we want a documentary crew hanging out with us all the time? It's such an invasion of privacy. They looked not only at us but at other filmmakers too, to make sure about the chemistry. And they chose us -- the rest is history.

"Harlan County, USA" is very different from "Shut Up & Sing." But the two movies are deeply political without being necessarily overtly political. In both of these movies, politics aren't an abstraction. Those striking coal miners and their wives may not have thought of themselves, at first, as being politically engaged people, and yet they were dealing with something that affected their lives so deeply. That's similar to what the Dixie Chicks have had to deal with. Is that something you were conscious of as you went into this project?

No, absolutely not. I guess whenever you go into a film, no matter what the film is -- any preconceptions that you have about somebody, whether it's Mike Tyson, or Woody Allen -- you let everything go out of your mind, and you pick up the people for who they are, at that moment, and go on a journey with them, travel with them. Allow them to come as individuals and people, without putting [on them] any of your own thoughts of what you think [their story] should be. Should it be overtly political? Should it be more human?

It's about them, and it's about the storytelling. It's about trying to see them as, in the case of the Dixie Chicks, really remarkable women, complex women, women who are the most incredibly talented musicians, who took a chance on themselves, and who wrote songs that are so deep and reveal so much about who they are.

The big thing for me, above all else, is their friendship, the deep bond that they have with each other. It makes me, in my own life, want to say, This is what you've given me, as a gift: Understanding how wonderful friendship is, and how short a time we're here, so it's so important to connect. And how strong we are when we're surrounded with people we care about. And also their whole role as mothers and wives, and the kind of courage that they have.

But you don't think about where you're taking a film -- it's where these people take you. And they take you to more remarkable places than you could ever dream of.

There have been so many political documentaries made in the past few years -- "Fahrenheit 9/11," "An Inconvenient Truth." How, in your view, has documentary filmmaking changed in the past 30 years?

I think people are appreciating documentaries more. I don't think the form has changed, because you look back on some of the films that were made in the '70s or '80s, whether it's "Hearts and Minds" or "Gimme Shelter" or "Grey Gardens," which people are just now starting to appreciate -- they're going to be making a feature film out of the ["Grey Gardens"] characters, and there's a Broadway show. But I think people want to connect with something that's real. And they're realizing -- something that I've known all along! -- that documentaries are powerful; they're entertaining. They take you to places you've never been. You meet people who are extraordinary or ugly or complex, just as you would in feature films.

That's one thing I love about your movies and about your sensibility. With so many of the current documentaries, you have guys in black hats and guys in white hats: Filmmakers want to make it very clear which side you're supposed to be on. And yet in "Shut Up & Sing," you have people who are teaching their toddlers to say they hate the Dixie Chicks --

"Say it: Screw them!"

Which is a horrible thing. But to present those people without judgment -- I think that's really hard to do.

I think that when you don't try to make it black or white -- at least for me -- you're then giving people who are viewing the film a way to make their own decisions, to really look at the complexities of the material and of the story. It's always so enlightening. You mentioned "Harlan County." You need to understand who the gun thugs are, the scabs, the company, the coal miners, their wives. And if you don't get into all of those different threads, you're in a sense selling out, because you're doing cheap shots. I don't ever want to do cheap shots in a film. People would say to me, "Why would you do a film on Mike Tyson?"

Why not!

I just found him so fascinating. Boy, you can really get to know who he is. And he has his own frailties. People wanted him to be the heavyweight champ of the world more than they wanted discipline. So their own dreams for him helped to push him into a bad place. It's just so interesting what you take from things. And so moving. You learn so much about human nature.

And the Dixie Chicks -- Martie's statement, near the end of the film, where she breaks down. And she talks about Natalie, and you know, from earlier [in the movie], how much her career means to her and her music means to her. That she would give that all up for that sense of peace for Natalie, is pretty extraordinary.

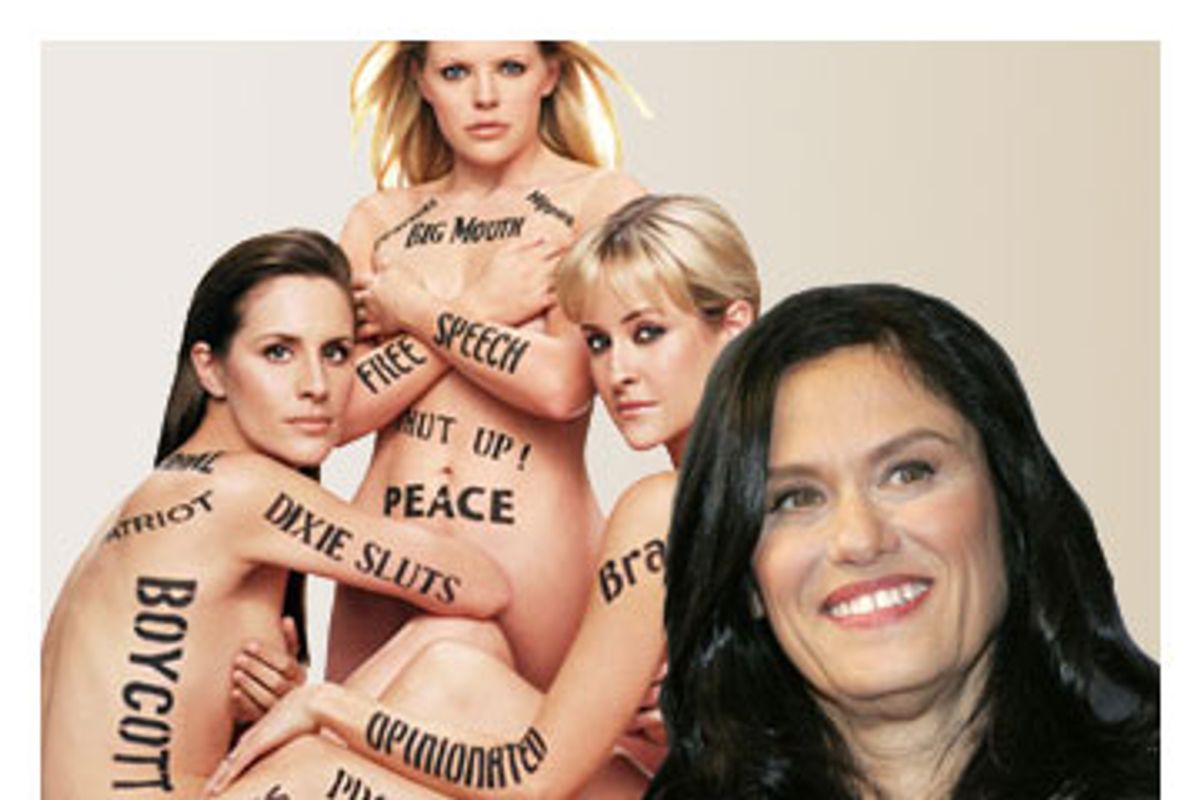

I saw "Shut Up & Sing" at the Toronto Film Festival, not at a press screening but at the premiere, which was fun because the audience was so excited about it. But there was one thing that bothered me. There's that scene in the movie where the band's publicist, Cindi Berger, is arguing with their manager, Simon Renshaw, about that Entertainment Weekly cover shoot, where the women appeared with slogans like "Dixie Sluts" and "Saddam's Angels" stenciled on their bodies. And the publicist thinks people won't get it. She says something like, "I think you're giving too much credit to the American public." And the audience I saw it with cheered. Obviously, it was a spontaneous reaction, and as a filmmaker, you can't control those. But it bothered me, because I felt it cut against the inclusive spirit of the film. I wanted to ask you how you felt about that.

I felt that, really, what that [scene] did was augment the strength of the manager, Simon, and the Chicks. That they're going to take a risk. And Cindy's job is to be a public-relations person, a spin person. So she's fighting from her area: "Come on, Simon, we can't do that, we can't put the girls in this kind of position, nobody's going to understand it. It's going to be an even worse backlash" -- that kind of sensibility.

And Simon and the Dixie Chicks, on the other hand, were saying, "This is what we're doing. We have faith in this kind of irony. We don't want to be spin masters. We want to be true to what we're feeling."

But what people take from it, once something goes out in a film -- one can't control. You can only think about, How do I see this? And you might see it differently than I do.

Sometimes it amazes me. For instance, "American Dream" -- the company liked the film; the international union liked the film; and the local people liked the film. And I thought, No, this can't be -- what did I do wrong? [laughs] You just have to put it out there, and depending who you are and what you see, that's how you read into something.

I don't know why [the audience was] cheering, or laughing. Sometimes people laugh and cheer at the embarrassment of something. Like, sometimes people might laugh at something gruesome. Or sometimes people slow up for an accident. Or maybe they thought it was funny, or they were laughing at her, rather than laughing at what she was saying. Who knows?

A large portion of the Dixie Chicks' audience has deserted them. Pop music, which includes country music, is supposed to be inclusive -- it's supposed to dissolve boundaries rather than harden them. I don't have any ideas for how they might do this, but do you think there's any way the Dixie Chicks can reclaim the audience they lost? Do you think they should even try?

I really shouldn't speak for them -- they should speak for themselves. But they can only be who they are. There are probably a lot of closeted Dixie Chicks fans who are going to go back to the Dixie Chicks. And the Dixie Chicks maybe feel that country [music fans] betrayed them, and country [fans] feel that the Dixie Chicks betrayed them. And I guess it's something that time will have to heal.

Or maybe it won't. I don't know. But hopefully, a lot of their fans will come back, and they'll have a lot of new people who never knew anything about the Dixie Chicks before [the incident], or who put them in a particular category.

I'm not Southern, but I'm often troubled by the way Southerners are portrayed or treated -- as if "Southern" and "redneck" were interchangeable. Do you feel any affinity for Southerners in particular?

No, I just feel that everybody needs an honest shake. And the only way you're going to get to know who people are and what they're about is by letting them express it. If you come into it stereotyping somebody, then you're never going to get to know them.

This film I worked on as part of a collective, called "Winter Soldier" -- it's about Vietnam vets. And there's this one guy in it, his name's Rusty -- and when he got back from Vietnam, every time he'd see someone with long hair, he'd just push them off the street, or say something nasty to them. Until one of them said to him, "If you keep doing that, we're never going to get to know each other." And so [Rusty] spoke to his wife about it, and she said, "That guy has a point." And that just changed his perspective.

One of the things I loved about "Shut Up & Sing" is watching Simon Renshaw talk to the band, trying to do damage control, telling them, "We should try to fix this, we should maybe do that." And as you watch Natalie, you can see all these feelings bubbling up inside her, and then she'll blurt out something like, "But we were right!" It cannot be repressed.

As it shouldn't be. Simon's also just a wonderful character -- he's like the fourth Dixie Chick in a way. He tries to bring a sanity point to it, but if he can't, and they just want to do their own thing, then he turns around and supports them.

That definitely comes through. A lot of managers would be angrier, more judgmental, more scolding.

Then he wouldn't last with the Dixie Chicks. That's not the way you get them to hear you.

Another thing that comes through so strongly in the movie is that even though they do have money, and nannies, the Dixie Chicks are still working moms, basically trying to hold it all together. They come up against a lot of the same things "average" working mothers come up against. And there's that stuff about the husbands cooking the dinner --

Well, just one! The others are very much independent guys. Adrian Pasdar [Maines' husband] is a terrific actor -- he's in a new pilot, he was on "Desperate Housewives," he's been in movies. Charlie Robison is just a phenomenal singer. He has his own band, and is also a rancher. So they're all men in their own skin -- and isn't it interesting that we're defending the men for a change? [laughs]

But [the Dixie Chicks] are still working moms. They still get up at 3 in the morning when their kids are sick, or when their kids cry. They don't have nannies taking care of the kids 24/7. Yes, they do have money, and that does make their lives much easier. But they're still out there struggling and stressing like everybody else.

And they're traveling all the time, with their kids, which has to be stressful, too.

But wonderful -- they wouldn't want to be without them.

We've already touched on this a bit, but what did you learn personally from spending so much time with the Dixie Chicks?

Here are these women who have balanced so much. They're mothers. They have seven children between them. They're wives. The bond that they have between them has deeply affected my life, as I never thought it would. I never thought I'd walk away from an experience with the Dixie Chicks saying, They have inspired me, and they have taught me what friendship is about.

Shares