It's hard to say which was sadder, reading last week about soul

superstar Curtis Mayfield's painful passing, or realizing the obituary

was getting bumped off the music news pages by the latest high-profile

arrest from the rap world. In this case it was Puffy Combs getting

booked on weapons charges following a shooting inside a New York

nightclub. The back-to-back dispatches were an unpleasant reminder of

how Mayfield's hope of using black music to reflect and uplift his

culture has too often been frayed by the collective actions of Combs and

others.

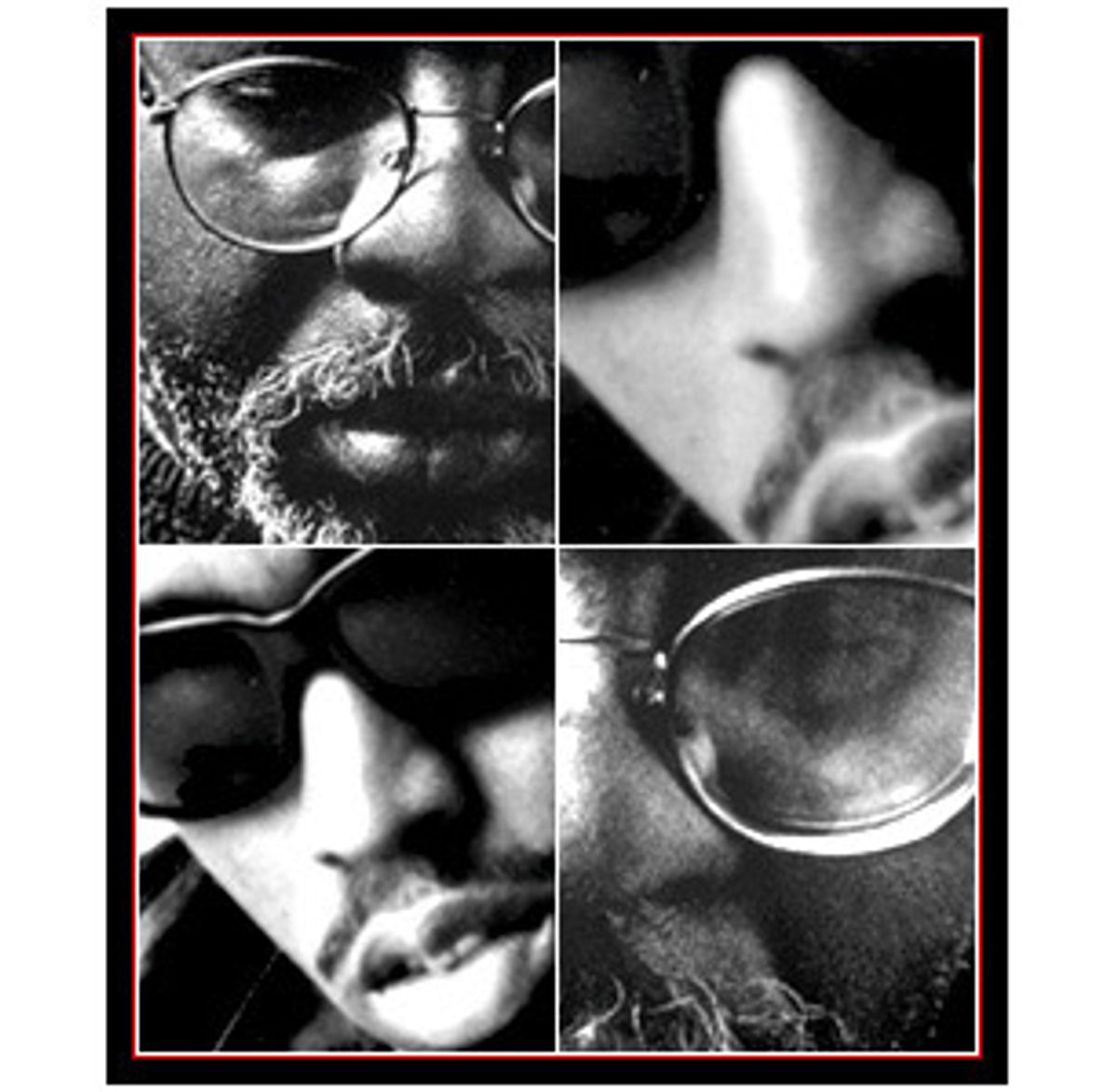

A towering musical presence among his generation, Mayfield redefined

soul and R&B music in the '60s and '70s with his soothing falsetto

voice, insightful, socially relevant lyrics and groundbreaking

guitar rhythms. A soft-spoken, religious and devoted family man,

Mayfield nonetheless embodied urban cool, sporting a gruff beard and

wearing waist-length leather jackets.

And at a time when Motown hitmakers were mum about social ills and the

dashed dreams of the big city (quick, name the label's '60s civil rights

or anti-war anthem, because Marvin Gaye's "What's Going On" didn't come

out until '71), Mayfield was penning songs such as "Keep on Pushing,"

"People Get Ready" and "We're a Winner." When heard crackling through AM

radio speakers, the songs spoke first and foremost to black America with

a message of perseverance and hope. Mayfield wasn't above having some

fun, either; En Vogue's sexy smash single from 1992, "Giving Him

Something He Can Feel," was a Mayfield cover.

Contrast the complex Mayfield with Combs and too many of his rap partners who,

benefiting from the musical inroads Mayfield made, now seem solely

interested in themselves and their riches. Combs' latest run-in with the

law -- prosecutors say the rapper pulled a semiautomatic gun inside a

club, then jumped into his Lincoln Navigator and led police racing down

Eighth Avenue, running 11 red lights -- came just eight months after he

was accused of breaking a record company executive's jaw. (Combs skated when the exec reportedly accepted the rapper's $500,000 out-of-court

settlement offer.)

Meanwhile, the same day last week when readers found out about Combs'

weapons charges, they saw wire reports that rapper Eminem, last year's

breakout star, who rhymed about killing his daughter's mother and then

stuffing her body in the trunk of a car, was being sued for slander by

his grandmother. She objected to Eminem's plan for an upcoming track that

may include using an old recording of his uncle who died in 1991.

This, just three months after the rapper's mother filed a $10 million

slander suit against him. He told the music press she was a chronic drug

user.

Meanwhile, over the same weekend, rapper Noreaga was busted on drug

charges. And of course just four weeks ago, superstar Jay-Z made

headlines when he had to post $50,000 bail after being arrested for

stabbing music exec Un Rivera at a New York club.

Several obituaries suggested Mayfield's seminal work, the No. 1

soundtrack to "Superfly" (1972), laid the groundwork for today's

hardcore rap music. Mayfield was certainly among the first to give

mainstream listeners a guided tour through ghetto drug life. And to an

extent, there are several now-familiar portraits in songs like "Little

Child Runnin' Wild" ("Broken home/Father's gone/Mama tired/So he's all

alone"), "Freddie's Dead" ("Another junkie plan/Pushin' dope for The

Man") and of course, Mayfield's soul classic, "Pusherman" ("I'm your

Mama/I'm your Daddy/I'm that nigga/In the alley").

True, Mayfield never would have used the overtly violent images NWA

opted for on "Straight Outta Compton," but the groundbreaking gangsta

rap group was, in a sense, picking up where the singer left off,

describing the hard-as-nails pain and frustration of ghetto life. And to

this day scores of rappers such as Lauryn Hill tap into Mayfield's

legacy by building songs around reliance and faith.

But the crucial difference between the celebrated soul singer and so

much of today's hip-hop is that while Mayfield chronicled the vicious

cycles of the inner city, he never glorified them. In fact, as he told

writer Alan Light during a 1993 Rolling Stone interview, Mayfield was concerned when

he finally saw the action-packed, blaxploitation classic about a Harlem

pusher looking to get out of the drug game. "You could see the surface

was quite glitzy with the clothes, and the cars -- in many ways it

looked like a cocaine commercial!" said the singer from his bed, where

he spent the last nine years of his life following an onstage rigging

accident that left him paralyzed. "That sort of pushed me the wrong way

when I was watching it."

Mayfield explained that the music to "Superfly" was written specifically to

counter the images of the film. "I did the music and lyrics to be a

commentary, as though someone was speaking as the movie was going." Not

surprisingly, Mayfield's sometimes preachy drug lament, "No Thing on Me

(Cocaine Song)," also from "Superfly," sounds like it was sung by a

man who'd seen too many friends fall to addiction.

Compare that with the approach of today's bestselling rap acts. Back in

early December when Jay-Z was booked for assault, an editor at rap

magazine the Source told a newspaper reporter the news was doubly

shocking because Jay-Z represented the "thinking man's rapper." Hmmm.

Here's a quick lyric sample from "It's Alright" and "Nigga What, Nigga

Who (Originator '99)," two songs off his 1998, four-times platinum "Vol.

2: Hard Knock Life" album:

"We can ill if you wanna ill, smoke if you wanna smoke

Kill if you

wanna kill, loc if you wanna loc

It's all right, you heard? It's

all right, yeah yeah

I need a ho' in my life to blow on my

dice"

"Motherfuckers wanna act loco,

Hit em wit, numerous shots with the

.44

Faggots wanna talk to po-po's,

Smoke em like coco

Fuck

rap, coke by the boatloads

Fuck dat, on the run-by, gun high, one

eye closed"

Mayfield, who infused his music with calls for community, respect,

self-determination and hope, no doubt would have been heartbroken to

think he had a hand in inspiring a generation of young stars who

broadcast to America a picture of black culture focused on guns, drugs

and whores.

Shares