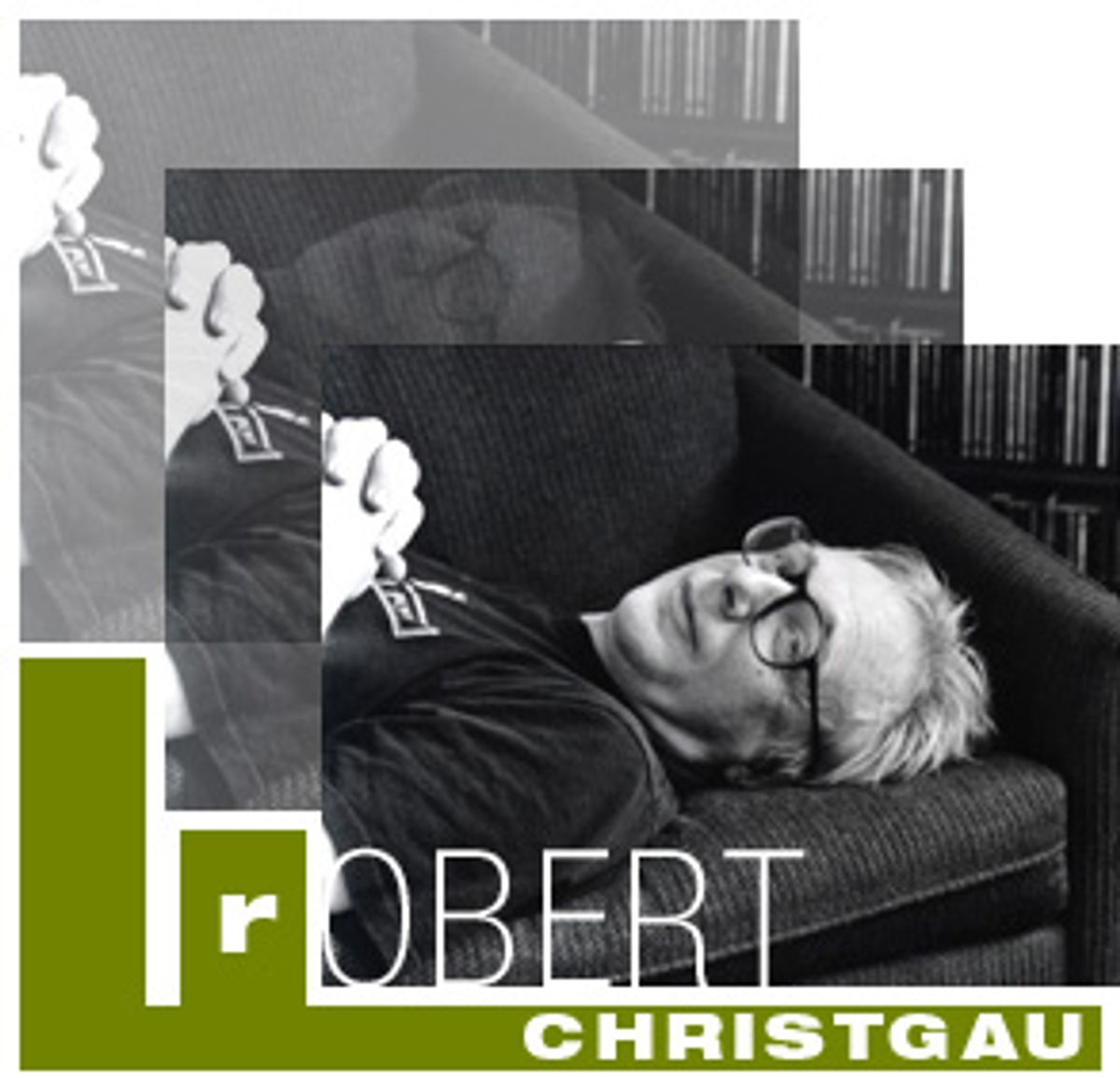

For 35 years, Robert Christgau has written about pop music, first for Esquire in its new journalism salad days and then, for fully 29 of the past 31 years, at the Village Voice, where he still holds a senior editor title. Over that time he has tracked, with unmatched energy and unflagging interest, the course of our culture's most protean art form.

It's also our most youthful art form; yet, at 59, Christgau still maintains a sympathetic ear for the music's newest sounds, even as he's matured into a sophisticated appreciation of world pop on a scale few American writers can claim.

His work is unmistakable: At Christgau's best, he's fiercely analytical, dispensing dense sentences that twist in on themselves and (sometimes) the reader, rife with allusions both academic and street and displaying both a ready conversance with theory and a scathing contempt for puffery.

He has lived in a book-strewn flat in New York's East Village for decades. He married Carola Dibbell in 1974; they have a daughter, Nina, now 15. Over the years Christgau has maintained combative friendships with critics like Ellen Willis, Greil Marcus and Dave Marsh, and mentored a generation or two of young critics, notably Ann Powers, now a staff critic for the New York Times.

The 28th edition of the Voice's Pazz & Jop Critics' Poll was published in March. A lineup of nearly 600 critics voted Outkast's "Stankonia" the album of the year. Created and still overseen by Christgau, the poll incorporates the views of ever-new generations of younger critics and can lay claim to having rarely missed talent when it first appeared, making it arguably the most comprehensive and respectable award operation in any medium.

Christgau continues to write a column, "Rock&Roll&," for the Voice and pens a monthly "Consumer Guide" of capsule record reviews. He has three recent books: "Grown Up All Wrong," a collection of his recent Voice essays; "Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s," the third assemblage of the Consumer Guide capsules; and "Any Old Way You Choose It," a reissue of his first, 1973 anthology of his earliest work.

We spoke to Christgau recently in New York.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

How do you feel about the notion of a rock canon?

I've been accused of being a canonizer myself and I'm pleased to say that that's now a complete absurdity.

Do you think you worked out of that way of thinking?

I think that the culture simply passed me by. Canonization is institutional. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is a canonizing institution. Jann Wenner has worked to make Rolling Stone the keeper of the canon since 1970. I don't like that, because he uses institutional power and he uses economic power to enforce those standards. Similarly, when MTV does one of its incredibly stupid historical rundowns -- which it does four times a year of some dumb shit or other -- it's using its institutional and economic power to enforce a canon. I just express my tastes. But I think that there was a time in, say, the '70s when my tastes were so in keeping with the conventional critical wisdom that I was a kind of a canon keeper.

Kind of an anti-canon canonizer?

I was and I wasn't. For the critics I wasn't. Maybe for the industry I was 'cause I always liked punk. But critics never had any problems with the Sex Pistols and the Clash; it was just the industry that did.

None of your books has presented your work in a canonizing way. Maybe specific essays do.

Somebody may well ask me to write a canonizing record book.

And would you?

If the money were right, I wouldn't hesitate to do it. But even then, Dr. Dre and Radiohead would not be in that book. Now Radiohead is the most important rock band in the world by acclamation. Bull fucking shit, you know. They suck. And whether I'll be vindicated or not I don't know.

What's the next thing after the teen boom?

I never prophesy. I've been saying hip-hop, hip-hop, hip-hop, hip-hop for a long time, and now I'll say hip-hop, hip-hop, hip-hop, hip-hop. I don't see any signs that it's slowing down. And obviously other stuff is going to go on. You know what I mean: The trend is no trend -- that's the trend. The trend is the proliferation of outlets, genres, audiences. That's clearly the case and it makes perfect sense structurally in terms of the economy and the way the society is structured.

You're not a doomsayer about audience fragmentation?

No, I'm not. But I also don't think it's a good thing that we've lost what's called the monoculture. I grew up with the monoculture. I don't think it's such a bad idea that people learn the same history in school. I think it tends to ground people and give them something to respond to and react against. But on the other hand, if 25 years ago you had said, "Oh, there'll be 50 different radio stations that'll all play different kinds of music and there'll be thousands of different songs on the radio," people would have said, "Oh really? That sounds great." Now they say, "Oh, it's the end of the world." Well, it's one or the other. Maybe it's neither.

You know, information overload is a phrase I've been using in my criticism for a long time. Change seems disturbing, threatening, fucking irritating, an affront to one's very existence. But it's not a good idea to base a career on it. I'm very anti-nostalgia and I'm very anti-golden age.

So what is the rap that a 58-year-old white man likes these days?

I tend to have very East Coast tastes. I'm slow on the uptake about things. I didn't understand that the first Wu Tang album was great when I first heard it. And now I'm curious -- I was listening all morning to the fourth Outkast album, and I suspect that there was more on those first two albums than I heard at the time. I have to go back and listen. It takes me a while to understand, because I'm not in that world at all and I have to get it solely as music. I have no cultural connection at all to it. And I usually have to read a lot about it and have it explained to me.

I've been pretty quick on the uptake about most things. And then there are things I don't like or get. Metal -- I don't think metal's as bad as I hear it as being. And were I a different person, I could probably write differently about dance music, especially the most recent phase of it, since 1989 or so. But I'm not that person and I believe the only person who can write well about that music has to spend a lot of time in clubs and do a certain amount of drugs, neither of which I'm ready to do. And then there are other things too. I don't get salsa.

It's not always so easy for lots of people to maintain such a high level of interest in the subject matter for so long either. How do you do that?

It's my gift.

You've never lost it?

Every once in a while there's a day or two when I say, "Gee, electric guitars, what an ugly sound." But I'm a very enthusiastic person. For sure I'm an excitable, fun-loving person. I enjoy life.

Do you think you're intimidating?

I'm told I'm intimidating, so I guess I am.

And do you like that?

No.

Has it ever worked for you?

I assume it has. But I don't think that's the way to relate to people. I'm not one for small talk. I don't have many regrets about being that way. There are times when it really seems inappropriate to me, and I try not to do it, or I wish I hadn't done it later. But as a general approach, no, I think it's fine.

How would you assess your character?

Honest, abrasive, hardworking, fun-loving. And a peculiar mixture of pretentious and unpretentious.

It's interesting that you didn't mention being a talent scout and mentor, because so many people credit you with not just giving them their start but shaping them.

I love being an editor, but I haven't been an editor in a full-time way for 15 years. I became a rather good writing teacher until I decided that no one could pay me enough for the time that it takes to be a good writing teacher. Give me [tenure], I'll go back to it. Make me an adjunct, forget about it. I love teaching writing. And it was a great pleasure to find writers.

Do you think the Voice has lost its relevance?

No. Has it lost its monopoly? Yes. Its formula has been fucked with, adjusted, so that we have Time Out, we have the New York Press -- which are two sub-Voices, both of which have their own functions and their own audiences. We don't control the playing field anymore. But I don't think that's unhealthy.

I'm proud to work for a newspaper of the left. I'm a leftist. And fuck everybody at the Nation who thinks that we're not really leftists.

What's the most dread question that you can imagine me asking?

It would have to do with talking seriously about what I think of the work of people who I like more than their work.

Who are the younger writers you like now?

What do you mean by "younger"? 'Cause the younger writers are all past 30 now. There's a whole bunch of people under 30, and I have more trouble sorting those people out. There are a lot of people who I'm not even aware of, and I think because there isn't anybody really guiding them in a lot of ways, there's a lot of shitty work being done.

You ask me to name who I'm proud to have worked with as an editor? I'd say Greg Tate, Nelson George, Tom Carson, Stanley Crouch. Both Chuck Eddy and Ann Powers were people who I got jump-started because I noticed them and gave them a passing shot. And I'm very pleased about that.

So who are your five favorite rock critics?

Most of them are over 40; the exception is Ann Powers. Greil Marcus, Lester Bangs, Greg Tate and Jon Pareles. Is that a self-interested list? Yeah, but on the other hand, why did I go to those people to begin with? Because I thought they were smart. I like Jon because what he manages to do in that daily context is pretty remarkable. I think he's as good a writer about the music of rock as there is.

Was Lester Bangs a good friend?

He wasn't a good friend. He was a good friend of my sister, Georgia, he was a good friend of Greil, who is one of my closest friends. He ate dinner at my house. We had a good professional relationship based on a lot of respect on my side and to a lesser extent on his. He had bad feelings about me sometimes. I said something to him once about Flaubert and the Ivy League that he never understood. I used to complain about people who talked about literature as if it went back to "Naked Lunch" -- and Lester was certainly in that category.

I'd come to realize that my education had prepared me in a certain way, that it had given me a context out of which to work. Not that it made me better than him, which I think is what he thought I was saying. What I would say is that having a good general education helps you to write criticism because you understand the consensus narrative about culture -- "consensus narrative" is a term my wife and I have been kicking around. You know, you understand what the conventional wisdom is about culture and then you can work against that.

Do you want to say a little bit about Greil?

Greil has been one of my closest friends since we started corresponding before we even met, in early '68, I think. I'm very unlike him in a lot of respects. He's a much classier guy than I am. There was a period of the better part of a year when he wouldn't talk to me because of what I said about Public Enemy. He felt I was defending their anti-Semitism. We didn't have the same position on it. He's a very loyal friend. It's of value for both of us.

How would you compare your approach to music and writing?

We started out two peas in a pod and now I think we're completely different. He has a much broader cultural range than I do. He's a much better educated person than I am, both autodidactic and in terms of his academic background. He cares about the fine arts in a way I do not. And his knowledge of politics is much more detailed than mine. On the other hand, I think that my appetite for music far exceeds his, and I think specifically that he hasn't had much feeling for black popular music since soul took a nosedive. That's almost 30 years ago. It's not that he pays no attention to it at all, but it definitely hasn't moved him the way it's moved me. He's not moved by George Clinton the way I am. He knows George Clinton is great, I'm sure, but he doesn't care about him like I do. And I think that's very important. I like rock -- it's meant a lot to me. But hip-hop is the music I think is strongest these days. And you know what? I have no connection to speak of with the hip-hop community. I'm sure that most of the people don't care at all what I think. But the music is there; it's there to be enjoyed.

How did you meet Ellen Willis?

Ellen was my first serious girlfriend after college, well after college. I had a long dry spell. I'd actually gone to junior high school with her and later ran into her. I was asked to write a story about the Free University for Commentary, the other magazine that called me up. She was working for Fact, Ralph Ginzburg's magazine. And she was at the free university trying to meet guys. I was in love with her soon enough. She didn't really know that much about pop but she understood it, I would say, inside of 15 minutes. We started developing this theory of pop together -- which we were going to write a book about, only we broke up first.

How long were you together?

From January of '66 till September of '69. They were interesting years.

Why did you break up?

She wanted to sleep with somebody else and I didn't want her to. We really felt the opposite way about some things. A lot of sparks flew and we're both really articulate and smart-talked to each other all the time.

So what about the rumor that you and Ellen were at a dinner party after you'd broken up and you threw a piece of pie at her?

Greil Marcus was sitting right next to her, and he's still my friend. That's one of the reasons I threw the pie at her, actually.

How is that?

'Cause I wanted to be with Greil -- that was the reason I was out there.

And she was monopolizing him?

In terms of my irrational motivation, that was certainly part of it.

Did it hit her?

Right in the face.

Did anybody ask you to leave?

No. It wasn't a dinner party, it was a big Grunt Records/Jefferson Airplane junket. There were hundreds of people in the room. It was at Winterland, I think.

Have you ever done anything like that again?

Probably, but I don't think I'm going to labor to remember it. When Carola met me, she was impressed by how often I got into confrontations with people on the street.

She was impressed by that.

Yeah. It happened probably three or four times the first year or two I knew her.

Were you trying to impress her?

No. And I don't do it anymore.

To what do you credit that?

Carola. She calmed me down. I'm not really a street-fighting man.

You're the marrying kind.

I am. And Carola had decided she was ready after a couple of years. We wanted to have kids together.

I know you've personally brought women into the business of rock crit. The field has been male dominated, however; that's a common perception.

I certainly know women who feel that way who I think got exactly what they deserved and I'm not going to name those names. I don't have a very p.c. view of this. I think that as in rock itself, there are certain -- I want to say prerogatives of discourse but that's not the right phrase -- certain usages (that's a word I often fall back on) that require a certain kind of forcefulness that I don't think women are as well equipped for as men.

Why?

I would say socialization till proven otherwise, but maybe that's not the case. It's an aggressiveness, I think, more than anything else. I teach Strunk and White when I teach college writing. Strunk and White -- that book ["The Elements of Style"] was originally written for ruling class white men at Cornell in 1920. I explain that to my students. I point out to them all the class biases in the text, and then I say, "You should learn how to do this, because this is how the enemy controls you when it's the enemy." I believe that you have to learn to master those tools. I think a certain number of women critics decline them, and it's to their detriment.

What about women in rock, or "women in rock"?

The best rock band going now is Sleater-Kinney, a women-in-rock band if ever there was one. One of the things about rock 'n' roll, and its excitement, is that it's about youth, and discovering your power. It's about growing up. It's about forming yourself in public. For many, many white guys, that drama doesn't seem to have many nooks and crannies anymore. But for women it's got plenty. And the reason that there were so many great female artists in the '90s is simply that they had emotional expanses out there that they had to explore and utilize and exploit that guys didn't have. It is definitely not a good time for that sort of thing right now. So far there are no women coming along -- whether they are pop stars, à la Britney [Spears] and Christina [Aguilera], or whether they're the likes of Aimee Mann, who seems to me to conform to an aesthetic of gentility that has always been the opposite of rock. There are always holdovers and residuals, but as an idea, I would assume it has not played out.

What has to happen?

For one thing, it's got to happen big. Hip-hop is really what's going on in pop music these days. And women have a foothold. But for the most part they're very ancillary and they tend to be members of crews being tossed bones. It's got to get better than this. It seems like the big women in that world then become R&B singers, like Mary J. Blige.

There is something very masculine and hard about the main thing one likes about rock 'n' roll. And one of the things you're saying to women is, "Don't be so fuckin' girly -- come out and do this." And maybe that's an unfair imposition. Maybe it's not right for a guy to make that demand. But it's nevertheless the demand I guess I'm making.

So you're not saying that women can't handle an ax the way --

I certainly don't believe there's any biological reason. There are probably biological things that women can't do, but playing guitar isn't one of them.

When did you know that you wanted to write about rock?

It wasn't there for anyone to know it was to be done.

How did it occur to you?

I had been a big rock 'n' roll fan in the '50s. I had a friend who subscribed to [Billboard competitor] Cash Box. I kept the Top 40, I bought a lot of singles, I did all that stuff. I went off to Dartmouth at 16. It wasn't a terribly good time for music and the radio up there sucked. And so there was jazz and folk music. I got into folk music, Joan Baez happened, I got out of folk music. I had always liked jazz too, and I really got deeply into jazz. And I was dimly aware of what was going on in rock 'n' roll.

After college I took this filing job, and WABC radio was on every night. The painter Bob Stanley, who was a mentor to me after I graduated, was my boss. We would talk about the songs -- early Motown, girl groups, all that stuff was great.

How did you start to write?

I went to Dartmouth thinking I'd be a lawyer. It lasted two weeks. I discovered literature, which had really never been presented to me as such, even though I was a really good English student and won the creative writing award in my high school.

I'd always loved to read. I wanted to write fiction. I spent two years trying to do it in my spare time and I was terrible at it. I'm not good at making up stories. At the same time, I was getting interested in pop. And I was interested in sports and sports writing. I discovered A.J. Liebling when I read an essay called "Ahab and Nemesis" in his book "The Sweet Science." It's one of the great essays of the 20th century. And I said to myself, well, I'm not doing too well with these short stories. If I could write one thing that's as good as that in my life, I'd be happy.

And I don't think I have. But I'm close enough.

So I began to think about journalism, about reporting. I didn't want to be a critic, but that's what happened.

Why didn't you want to be a critic?

Because it wasn't creative -- although people told me I should be a critic, that it was something I had a gift for. 'Cause I certainly had a lot of opinions. One of the things you need to be a critic is not only opinions but to think that they're important.

I went to work for the Newark Star-Ledger at a suburban feature service. I did the police beat and found I wasn't good at that either because you have to hang out with the policemen. I'm not somebody who likes to sit in bars and talk to people. I like to sit at home and read. I'm not a schmoozer. And good reporters tend to be schmoozers. I admire it greatly, but I don't have it.

Somebody had died in Clifton, N.J., on a macrobiotic diet. I went to New York magazine [with the story] and Tom Wolfe was actually there with [editor in chief] Clay Felker. I'd been a copy boy there for a few months so I had some notion of what I was doing. They gave me the assignment on spec, I worked my ass off, I gave it back to them in two weeks. And it was an award-winning piece. Esquire called me up. By the end of the second year [there], [editor] Harold Hayes was telling me that he had heard rock was dead and could I please write a piece saying it wasn't true.

I wrote this piece about how rock 'n' roll wasn't actually dying and why it wasn't going to. And they didn't print it. And then they let me take it over to the Village Voice and I asked if I could write there.

What do your parents do?

My father is a fireman who at the age of 34 got a scholarship to NYU, and went at night while working two or three jobs. He used to work an 80-hour week all the time -- and go to college. My mother is a housewife. She became a school secretary a little after I went to college and basically ran whatever school she was in. She's not bossy but she's very smart.

What were you like as a child?

I come from a very religious background. My parents came from churchgoing families and they moved to Flushing [in Queens, N.Y.] and ended up in this extremely theologically conservative church, which was full of nice people, most of whom were displaced Southern Baptists. And they became born-again Christians and pillars of the First Presbyterian Church of Flushing. Still are.

I lost my faith when I was 15. I was a very thoughtful kid. I took the biblical teachings very seriously; I thought about what they meant. The idea of predestination, for instance, fascinated me. The idea of God's omniscience fascinated me. I thought about it a lot. The ideas of the church really stimulated me.

So you were more intellectually drawn than emotionally?

I guess so. It's not uncommon for kids in those churches to wonder if they're really saved, and I did. I grew up in the belief that I had eternal life. I was the second member of my family to go to college. I took philosophy, which everybody told me not to take 'cause it was too hard. But that was the kind of thing I was interested in, ideas. And boy, it put me in a funk that lasted for years. I became an existentialist. I worried about death all the time. I was depressed for years.

And you think it was triggered by this philosophy course?

Yeah. Having grown up in the certainty of the faith and then having to learn to live without it. It was a struggle. But I think in the end, having grown up with that faith has been very good for me, just like being a first-born son has been very good for me. I have a lot of confidence that I think comes from my childhood training.

You must make some connections between that early faith and your more secular passion.

I think it informs everything I do. And it was very hard on me sexually; I resented it for that reason for years, 'cause I didn't know what to do about sex. I didn't lose my virginity till the summer before my senior year, because I felt it was wrong in some way. Once I realized what I'd gone through and how much time I'd wasted, I was very mad about it.

So as the first-born son in a religious family, you had a lot of pressure to be a leader and an upstanding son, carry on --

I don't think I was pushed. But I was taught to compete. My father was a very competitive guy. He would play cards with me, and play to win. And, you know, that made for somewhat problematic relations in some respects, but once again, I think it was good for me. I tried to do it with my own daughter -- it didn't work at all. Then I tried to not win and that didn't work either. My father was very athletic, and although I'm not a great athlete, I always played sports. I know there's a lot of that in me. I'm a good competitor.

How has having a child, specifically your daughter, changed your criticism or affected your taste?

I don't think it's affected my taste very much at all. Except I probably would not have gotten into the Backstreet Boys without her. And I'm very glad I did 'cause there are things the Backstreet Boys have done that I think are really great. And I can write about teen pop with sympathy. Plus, Nina's very musical -- she has an enormous amount of specific insight to provide, as well as info.

She likes to share it with you?

We talk about music a lot. She has great ears.

Why does music mean so much?

I began this having a very political and sociological view of it, and I still do. But when you immerse yourself in music over a long period of time, the notion that arts have formal properties that transcend their apparent meaning becomes irresistible. You know, what is it about music? There are ideologues who believe that music is what makes us human.

There's a musicologist named Christopher Small, who I wrote a piece about recently, who makes that argument pretty strongly. I resist that sort of generalization because I think it's always a little dangerous to take what it is that you care about and make it the test of what's human. That's led to a lot of bad things in the world. But it seems to be a pretty deep thing that people really like. And I don't believe that the reasons they like it have been very well understood. Small's idea, by the way, is that rather than its being about time, which is the usual fallback position that people have, it's about relationship. The notion that it's about time is a very Western European idea. I must say I find [Small's idea] a completely compelling formulation, 'cause I've always thought the time idea was a little suspect.

So he says it's about the relationship of things to each other?

To anything. At every level.

It's very bodily related.

Yes it is. But many people believe it's about sex. I haven't believed that for a long time.

No, that's too narrow.

Right, much too narrow.

What do you need to be a good critic?

A critic's job is not to like everything that's good at precisely the right moment. If you could do that, my guess is that you'd be kind of a boring critic, 'cause there has to be some idiosyncrasy and weirdness in there. That's part of what's fun about it. Or fun about reading good criticism.

Kids ask me, "How do you write a good record review?" I always say, "The first thing is to know what you like and the second thing is to know why you like it." The temptation is to like what you should like -- not what you do like. You have to resist that temptation. And then once you know what you like, another temptation is to come up with an interesting reason for liking it that may not actually be the reason you like it. That's not a good way to write criticism.

It's a discipline. You have to learn how to do it. You have to know when you're actually feeling pleasure, and then you have to be honest with yourself and look into yourself until you figure out why it is exactly that you like it. And you know the Consumer Guide, which is what I'm best known for, there's still people out there who believe I just dash the shit off.

Is there any place that you wish you had had a career instead of the Voice?

The one place I would always have liked to have worked and I've now come to understand that it will never happen -- and I'm probably much better off for it -- would be the New Yorker. Who wouldn't? They pay real good and they let you do what you want. That's always what I wanted. But it's obviously not a match.

What I'm most pleased about is that I'm a professional writer and I get to say something that closely approximates what I might actually want to say. I'm very sensitive to language. My style is forbidding -- I understand that. I know my sentences are too long and that sometimes the references are too obscure. I'm not always happy about it but it seems to be my style. I have a lot of craft. And I'm good at imparting it to other people, at showing people how to think about stuff.

What about these designations for you, such as the dean of rock criticism?

I made that one up myself. I mean, I try to be jokey about it. Maybe in the early '70s there actually was some sort of weird truth to it. I said it at a party for the Fifth Dimension in either 1970 or '71. I was a little drunk and I was introduced to somebody and they said, "Who are you?" And I said, "Oh, I'm the dean of American rock critics." I thought it was funny, so I stuck with it. There are people who don't think it's funny at all; they think it's awful -- a lot of people. I bet Russ Smith [editor of the New York Press] thinks about it every night.

MTV, yea or nay?

I hate it. I mean, there was a brief moment ... But it has nothing to do with music. That's why I hate it. For a while it provided an alternative distribution network, and another set of values by which music could be disseminated. But even in the earliest times there were too many conventional notions of beauty impinging on [it].

What about radio?

I don't listen to the radio. But that's a professional peculiarity. Unlike Nina, I can't listen to two things at once. I spend all my time listening to music, so how am I going to play the radio? I think that's too bad. First of all, it connects you to the culture at large, the musical culture at large. And the second thing is that it surprises you. There are songs that actually reveal themselves to you in that kind of saturation. A song like that which broke through to me anyway was Cher's "Believe" -- which I think is an absolutely great song. It's a song that I know about from the radio, from Nina playing it. [The Backstreet Boys'] "I Want It That Way," which I now regard as one of the great pop songs of the history of rock 'n' roll, basically got through to me that way.

You mentioned music, journalism and criticism as being the tripartite focus of what you do. What about historian?

I won a Guggenheim in '87 to study the history of popular music for a book that I have thus far not written, I'm sorry to say. I have a great command of the history of popular music. But I don't regard myself as a historian.

Why?

I've never taken a history course in my life.

But you make the point in your introduction to your recent collection, "Grown Up All Wrong," that this book can function as a history, as if the music can be used as a prism.

It's a reporter's, or critic's, diary more than it is anything else. And it seems to me that "Any Old Way You Choose It" functions as halfway between a specimen and an analysis. It's not either. "Grown Up All Wrong" is a much better written and more authoritative book. I think that my writing has improved enormously since I got to the Voice. The primary reason for that, if there has to be one, is my wife. Carola cares about language. That was really my passion, and Carola got me back into it. So I'm interested in language. I'm interested in what they used to call diction when I was studying poetry. I don't think the term is current anymore.

There's a sentence from Thomas Browne's "Urne-Burial" that I encountered as an undergraduate which uses, in a piece of very formal discourse, the verb "to piss." To piss on their graves. Well, it's a sentence I still show my students. I like mixing levels of discourse. I'm very interested in slang and the colloquial. I understand that that means that my writing may not stand the test of time. So fucking be it. Because I don't believe that that's what you sit down to do. You sit down to write as well as you can right now and then just see what happens to it.

What records do you go back to over and over again to make you feel better, like comfort food, a Beatles or a "Let It Bleed"?

There is no single record that I go back to that way. The fact of the matter is that there isn't any one Beatles record that I feel that way about. "The Beatles' Second Album," I guess, is the one I like which I still only own on vinyl, which makes it less convenient to use. For the most part, records are not really comfort food. There are too many records in my life for me to go back to any one of them. As I say in the introduction to the book, my favorite record is "Mysterioso" by Thelonious Monk. It's not a pop record. Is that comfort food? Even now, not exactly. Even after 45 years of absorbing bebop I don't believe that Monk's chords are exactly comforting. It's more about reaccessing a certain style of surprise than it is about being comfortable.

Do you have a top five artists of all time?

Louis Armstrong, Thelonious Monk, Chuck Berry, the Beatles and the New York Dolls. Those are the ones that mean the most to me. The reason the Dolls are in there is that there ought to be something that was a skyrocket that didn't prove to last. And for me they were a life-changing band. Al Green and George Clinton would probably be my next two. If there were a woman, it would probably be Billie Holiday. The artists that have meant most to me in the last 10 years are probably Pavement and Sonic Youth. Sonic Youth, of course, once called for my death.

Did that endear them even further?

No, it didn't. I hated it. At first it was in "Kill Yr. Idols," where they actually did call for my death.

That's scary.

Yes, because there are nuts out there, you know. Then there was the Flexi-single and someone suggested they call it "I Killed Christgau With My Big Fucking Dick." Which I then listed as in my top 10 singles only at Carola's suggestion. I called it "I Killed Christgau With My Big Fucking Dick and Now It Don't Work No More."

Do you agree that magazines and journalism in general have changed so significantly in the last 20 to 30 years that they may no longer be the best forums for the kind of critical opinion that you care about?

I don't think it's quite as bleak as that. I'm very lucky to be at the Voice, although there are constraints that didn't used to be there, and I don't like those constraints. I think one of the best pieces I've ever written was a piece for the Voice about Woodstock '94. It's 8,000 words long and probably wouldn't run in the current Voice. But there are many other places where it's possible to do good, serious work at some length, starting with the New Yorker, Harper's and the Atlantic. None of which happen to be right for me, but it would be silly to act as if no good work was done there.

What do you want to do next, besides your weekly journalism?

I've been asked to write a long essay on minstrelsy for Transition magazine. Really long. When am I going to find the time to do it? I'm working on it. I know a lot about minstrelsy. Blacking up is an old story in American culture. Blacking up is the source of all American popular culture. The minstrel show is the source of American popular culture. There is no other source. It's the source.

And yes, I would like to do some version of the book I got the Guggenheim to write.

Which was what exactly?

Well, it was proposed as a history of popular music.

International?

Yes. That was part of the idea. 'Cause nobody ever writes -- there are histories of popular music that are about individual nations.

How far back would you go?

Ancient Greece. The idea would be to do it all in one book. If I can do the 20th century in 3,500 words [in "Let's Get Busy in Hawaiian," Village Voice, January 2000] ... My plan now would be to do it as two volumes, one before World War II and then another one afterward.

You are a historian, really.

If I write it, yeah, well then I'll be a historian. Just keeping up is very, very time-consuming and engrossing.

I don't think anybody is as thorough as you are.

I listen to more and I listen to it more times. My entire life is constructed around those facts. I'm not always so sure that's right, and I think it has its drawbacks, critically. As I say in the introduction to the latest Consumer Guide, the great problem in my life is that once I give a record an A, I'm not sure I'm ever going to hear it again.

Is there ever a time when music is not on?

Yeah, yeah, there are -- but it's to be polite. Carola is incredibly tolerant. And you should be here when Nina's here because Nina has my habits; only Nina does literally listen to two or sometimes three different pieces of music at the same time. She has her radio on, she has the television on and she has her earphones on listening to her CD player. That I don't understand. I have great respect for her ears, but sometimes I wish she'd turn it down a little.

"Turn down that music!"

No. Because it's making it hard for me to hear my music.

Shares