A television news reporter is doing a story on a man who murdered both the ex-wife he was planning to remarry and her lover. Fixing the camera with a stern face and an even sterner voice, the reporter intones, "Well, the marriage is definitely over now!"

Have you stumbled across Ted Knight as the hapless Ted Baxter on a "Mary Tyler Moore Show" rerun? No, you've tuned into the WPIX "News at Ten" (the May 28, 2004, broadcast, to be specific) in New York City and heard, courtesy of reporter Vanessa Tyler, a pretty good example of what passes for journalism in local TV news these days.

Local newscasts have long been criticized for the "if it bleeds, it leads" approach and for reducing news to info bytes, though since the latter is becoming the standard in all journalistic media, it seems unfair to single out local TV news for condemnation. Most local newscasts are a predictable mix of metro news, national news recaps, consumer segments, blatant plugs for the parent network's programming, entertainment (you should pardon the expression) reporting, the sports segment and the segment that the cartoonist B. Kliban once identified by the words, "And now here's the weather with our weather asshole."

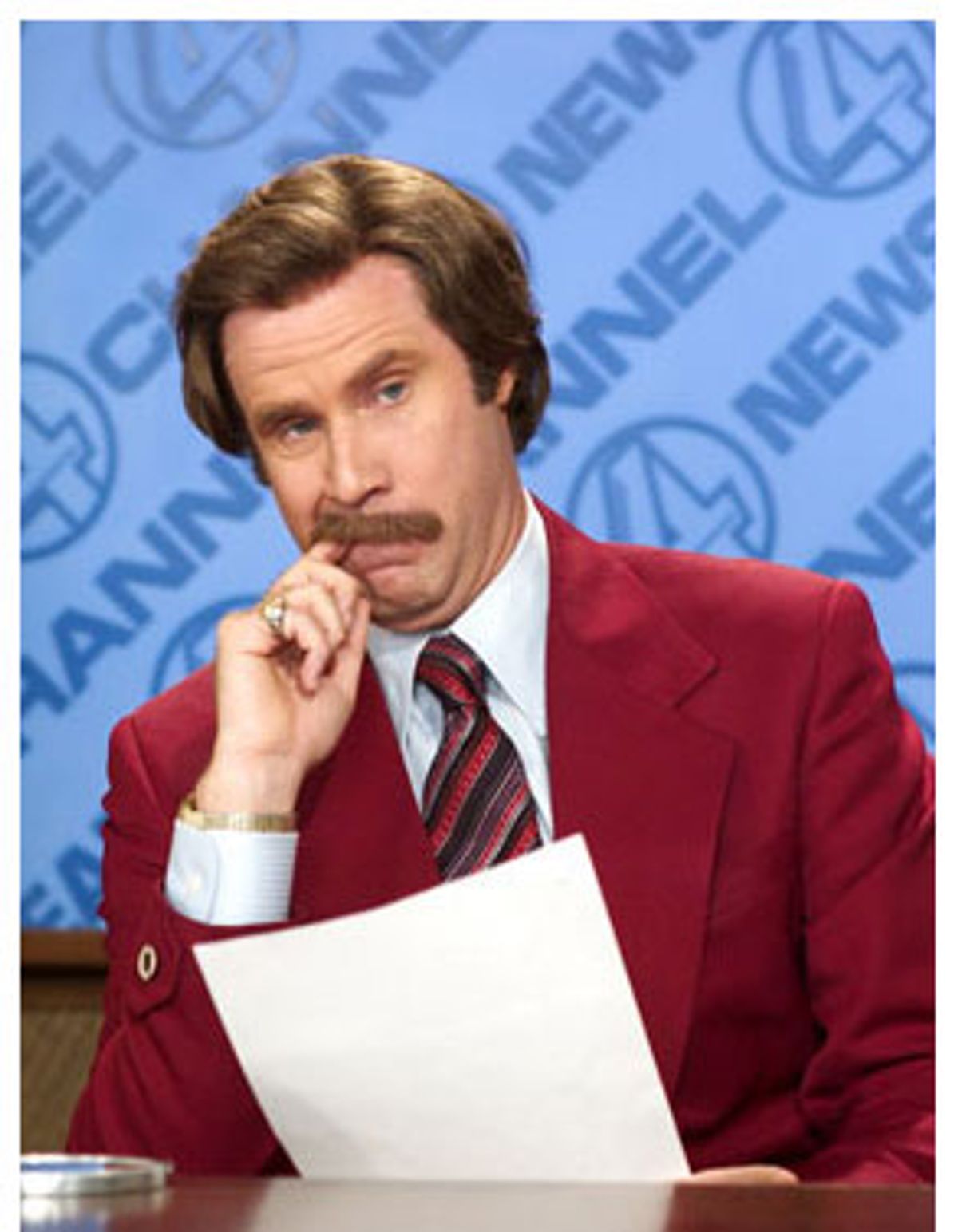

The Will Ferrell vehicle "Anchorman," opening Friday, looks as if it will be the latest in a series of potshots at a target that's become easier and easier to lampoon since Ted Knight's Ted Baxter and Chevy Chase's inaugural "Weekend Update" narcissist. But the truth is, what is really out there is often beyond parody. According to the Project for Excellence in Journalism's State of the News Media 2004 report, local news has lost roughly 20 percent of its audience since 1997. The Project goes on to suggest why that isn't a cause for mourning, saying, "there is too little evidence that it is committed to improvements. Indeed, most of the evidence would seem to suggest the opposite." The truth is that the real culprits are the local news outfits themselves and especially the larger corporations that, thanks to deregulation, own more of them than ever. They care most about maintaining their profit margin by keeping costs low, the final product be damned. Not to mention its viewers.

Watching a random sampling of local news broadcasts in New York, Boston and Denver from the past few weeks reveals the usual grim picture -- clichés, bad grammar, imprecision, a tin ear for the sound of language -- but also a penchant for melodrama that cheapens stories. And, at the worst, a failure to report stories accurately. I should say that there was nothing scientific about my survey, nothing that deserves to be called methodology. I simply sent out e-mails to friends in various cities asking for a random sampling of their local news. In New York, I stuck a tape in the VCR and set the timer to catch various broadcasts from 5 p.m. to 11 p.m. on the same day.

What I found was that the happy-talk approach that emerged in the '70s has not entirely gone away, rearing its dippy head in moments of forced banter between the anchors ("He's a fighter in't 'e?" asks Denver anchor Mark Koebrich after a story about the rehabilitation of a high-school football coach hit by a truck). Given the context, the effect is almost always grotesque. "See? There is some good news," Natalie Jacobson, the anchor at Boston's WCVB, assures her viewers after a story about a state trooper delivering a baby on the highway. Then, following a brief mention of Bill Clinton's "60 Minutes" interview, Jacobson says, "Also ahead, the deadline draws closer to the threatened execution of Paul Johnson." So much for good news.

But happy talk has to share space now with what can only be called the Ted Baxter approach. The anchors affect a furrowed brow; those who are able to do so add the flourish of a slightly raised eyebrow. Nodding -- precise inclinations of the noggin used to punctuate sentences and convey to the viewer that this is serious stuff -- is crucial to this style of reporting. And everyone's voice assumes a stentorian tone, a tone of voice that gives a fire or car accident or a murder exactly the same weight as a potential terrorist attack. It's the opposite of the soporific NPR tone, but the effect is much the same: to assure us that everything exists on the same level and that nothing really matters. Given that sort of equivalency, the following lead, from anchor Kaity Tong of New York's WPIX (the WB 11), makes perfect sense: "More medical news now: One of the Olsen twins is dealing tonight with a very serious eating disorder."

If Ted Baxter is in front of the camera, meanwhile, it's beginning to look more and more as if Jerry Bruckheimer is behind it. Location shooting is often done by Steadicams that aim to convey a vertiginous urgency to every story. (WNYW, the Fox affiliate in New York City, uses that camera style inside the studio.) And in the studios, the copious displays of computer graphics are no longer just hovering over the anchor's shoulders but interrupting the stories themselves. On WHDH in Boston, a breaking story is introduced by a "whooooshhh" sound effect and the graphic "THIS STORY NEW AT 11." Did anyone expect it to be old?.

But we've become so used to this flow of cliché and sensationalism and stone-faced idiocy that it's easy to let newscasts wash over us. Start paying attention to what the anchors and reporters are saying and you'll find local TV news has little use for words anymore -- at least as tools used to convey specific information.

Local TV news can make you wonder if the basic model for journalism is still the five W's and the one H. Story after story is introduced with the equivalent of the jacket copy used to sell books. On Boston's CBS affiliate, anchor Paula Ebben gives a hepatitis scare at a local fast-food restaurant a horror-movie spin: "They went out for ice cream or maybe a hot-fudge sundae, but tonight thousands of people in Arlington are on edge because of a serious health scare." The affiliate seems to have a penchant for this type of reporting. Reporter Beth Germano begins her account of a teen's drowning in a quarry with, "The lure of a warm night may have proved irresistible for a Methuen teenager and his friends." (She later tops herself with a line about how the boy "couldn't hold on in the cold, murky water of the quarry.") And anchors Lisa Hughes and Joe Shortsleeve pay homage to the hackneyed in this intro to the story about a teenager's disappearance 27 years earlier:

Hughes: "A young girl's disappearance has haunted a police officer for 27 years."

Shortsleeve: "Tonight there's new hope that a local pond may hold the clues to this mystery."

Another example of triteness in the face of death: Jim Watkins of New York's WPIX begins a report on a shooting with, "The family of a 15-year-old girl from Florida is grieving tonight because she will not be returning home."

Clichés abound in TV news writing: "It was a moment that stunned many Connecticut voters and changed the life of Lt. Gov. Jodi Rell." (John Noel, WNBC, New York); "Tragedy struck around 10:30 last night in this Long Island neighborhood." (Cathy Hobbs, WPIX, New York); "Tonight, time may be running out for an American held hostage in the Middle East." (Shortsleeve, WBZ, Boston). Elsewhere, a Harlem charter school threatened with closure is "fighting tooth and nail"; the battle over gay marriage "rages on"; Paul Johnson's family is "trying to keep hope alive."

Apparently, when the planets align, one image can make the rounds as if by osmosis. Here are a number of excerpts, all from the June 22 broadcasts of New York stations regarding Bill Clinton's Manhattan book signings:

"Well, you've probably been hearing about this -- former President Clinton is attracting crowds like a rock star." -- Ernie Anastos, WCBS

"The publication of that book has energized and galvanized his supporters and elevated him to near rock-star status." -- David Diaz, WCBS

"Well, it's been called Harry Potter for adults. Tonight President Clinton's new book is out, and it's creating a rock-star atmosphere for the leader turned writer." -- Sade Bederinwa, WABC 7

"Everywhere Mr. Clinton appeared today he was greeted like a rock star." -- Liz Cho, WABC

"Former President Bill Clinton was treated like a rock star on Fifth Avenue as his new book, 'My Life,' flew off the shelves." -- Glenn Thompson, WPIX

Perhaps those are preferable to the Northern cluelessness shown by WCBS's Ernie Anastos, who introduced the segment as "the book signing for the man they call Bubba." How would Anastos feel about, "And now the news, from the man they call Zorba"?

Along with failing to guard against cliché, there's a general inattention to grammar. Jennifer Miller of WCBS has this in a story on the Kobe Bryant case: "Bryant's team has criticized detectives of shoddy police work at the hotel." Jim Benemann of KCNC, the CBS affiliate in Denver, says a recent warning about suspected terrorists in the U.S. is "something we will be keeping very close watch of." David Diaz, reporting on the advance printing of Clinton's book for New York's WCBS, unleashes this nonsensical equivalent: "The book's huge advance printing has not been matched by its reviews."

Tin ears are ubiquitous. Anastos begins the story of the discovery of body parts with "A gruesome sight. Two skulls have been found by workers at a Long Island excavation site," failing to hear the repetition of "sight" and "site." And from WABC there is Liz Cho's unfortunate, "One man is dead, shot in the head," which you would expect to be followed by, "They stopped him cold with six ounces of lead. Let's go to the Cat in the Hat, already on the scene!"

There's obviously more chance of error and imprecision when reporters have to speak off the cuff to fill in a segment. But that doesn't mean there should be more tolerance for those errors. Here's Phil Lipof of Boston's WHDH speaking about the possibility of riots at the Democratic National Convention: "Just a little over a month now," he says, "the DNC comes to Boston, along with its many protesters, some say tons of protesters." Tons? Who's going to weigh them to be sure? (I estimate that roughly 50 protesters would be needed to qualify as "tons.") Lipof ends the report with: "No one knows for sure if the DNC will get out of control." Again, note the imprecision. It's not the convention that anyone fears getting out of control, but the protests it will attract.

The sloppiest on-the-spot reporting I saw was on the June 22 edition of WPIX New York's "News at Ten." The broadcast that night led with reporter Marvin Scott on the scene of a subway shooting. This is a transcript of Scott's report:

"This is a very active crime scene, all this unfolding about an hour ago on the Seventh Avenue No. 1 line. Let's take a look at some of the video of the police activity. Scores of police and detectives on the scene. They're questioning more than a dozen witnesses. I spoke to one woman, Pauline Griffin, who was two cars back from where the shooting occurred. She said she heard two distinct shots, and the reports are all unconfirmed right now. Apparently, there was one shooter on the platform. When the doors of the train opened, a shot rang out, a man who was inside the train fell forward. Apparently, two shots. The victim, no identification at the moment, has been rushed to St. Vincent's hospital in very, very serious condition. Police reported that he was in cardiac arrest when he left the scene. They are searching for one to three possible suspects. Male -- the victim is described to be a male in his 20s. And the suspects, two or three suspects being sought, all male, black, ages unknown. Police have no idea what motivated this whole shooting. They are here questioning witnesses who have not been exposed to the media still standing here at Seventh Avenue and 23rd Street. A story still unfolding but what we know right now -- a man in cardiac arrest shot at least twice on the No. 1 train on Seventh Avenue, where we're reporting live right now. Marvin Scott, the WB 11 'News at Ten,' now back to you guys in the studio."

Scott's report is, judging from the videotape he shows, more chaotic than the crime scene. It takes him nearly halfway through the report to even tell us what happened (a man shot on the No. 1 train at the 23rd Street station). Even then Scott's reporting contradicts itself. The number of shots fired keeps changing from two ("she heard two distinct shots") to one ("a shot rang out") back to two ("Apparently, two shots") and maybe even more ("shot at least twice"). "Apparently" is, apparently, Scott's favored rhetorical device. He uses it twice here and three times in his follow-up. Here, it makes hash of his report. Listen to this phrase "... the reports are all unconfirmed right now. Apparently ..." Nothing can be apparent if all reports are unconfirmed. And Scott's next dispatch from the scene, halfway through the hour broadcast, shows just how sloppy he was here. Here's the transcript:

"Well, Jim, yes, the victim has died at St. Vincent's hospital. He was brought there in cardiac arrest. Apparently he had been shot in the head and once shot in the face. This all happened around nine o'clock on the Seventh Avenue line, the No. 1 train. A lot of police activity here right now, as you can see. Police have pieced the story together like this. Apparently two men, the suspects, boarded the train at 18th street. The victim jumped on that very same train just as the doors were closing. There was no contact between them. And as the police are telling it, as the train approached 23rd Street station, the two men approached the victim. No words, no argument, nothing was said. Suddenly shots rang out, two shots. That's what witnesses on the train are telling police. Apparently, there are more than a dozen witnesses. Some of them being led away in tears to the 10th Precinct where they are being questioned right now by detectives. Two suspects ran from the subway. They were last seen running southbound on Seventh Avenue. They were said to be in their 20s, male, black, one bald, and one described to be wearing jeans, white T-shirt and carrying a knapsack. Police say right now they're mystified. They're wondering whether something may have occurred before the three men entered the train which all ended in this shooting tonight. We're live on 23rd Street on the west side. Marvin Scott for the WB 11 'News at Ten,' Kaity back to you."

The shooter who was waiting on the platform in the first report has become two shooters inside the train in the second, a contradiction that could have been avoided if Scott, knowing, as he said, that all reports were unconfirmed, had simply reported a man shot on the train. Even in this follow-up, Scott's presentation continues to be distracted, the narrative of the events interrupted by extraneous details ("A lot of police activity here right now as you can see ... Some of them being led away in tears to the 10th Precinct where they are being questioned right now by detectives").

Even written reports that have time to get it right sometimes don't. A WCBS report on the Bush administration's response to revelations that it approved torture refers to the release of documents that "are intended to counter a growing perception the Administration authorized torture as an interrogation technique." That is not a perception, but a fact. On the same day, New York's WABC got it right, reporting of one of the documents, "In another, Bush claims the right to waive anti-torture laws and treaties."

And then there is a general squeamishness when it comes to sex or profanity, which can result in some bizarre meanings. Anchor Bill Stuart of KCNC in Denver reports on a serial killer who has confessed to murdering five "prostitutes," and notes that the suspect may be linked to the death of two "women" in Phoenix. Maybe the women in Phoenix were not prostitutes -- does Stuart mean that the prostitutes in Colorado weren't women? Yes, prostitutes can put themselves in dangerous positions. But Stuart's description of the Colorado victims has a "Well, what do you expect?" quality that implies the murders were predictable, if still regrettable.

The same station reports that Colorado University president Betsy Hoffman, in a deposition investigating alleged rape by members of the university's football team, is asked if she thinks the word "cunt" is degrading. She answered yes. But, a medieval scholar, Hoffman is reported to have added, "in some contexts, it could be used as a term of endearment, such as Chaucer's 'Canterbury Tales,' an epic poem written in the 14th century." Forget the condescension of finding it necessary to tell viewers what "The Canterbury Tales" is; the real condescension here is watching adults talk to other adults using the phrase "the C-word." This isn't just an area where TV news is to blame. The same namby-pamby approach rules in newspapers. I had to read three stories in the New York Times before I could piece together what Dick Cheney said to Patrick Leahy. And I still don't know whether it was a verb ("fuck yourself") or a compound verb ("go fuck yourself").

Maybe it's silly to expect "cunt" to be bandied around on a 4 p.m. newscast, but there's nothing to keep the station from warning people that the following story contains strong language. The question here is do journalists have a duty to keep us informed about what officials say or not? Most news isn't fit for the ears of decent people -- what difference does a cunt or two make? The Colorado report recalled the mid-'70s when Gerald Ford's Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz was reported by the press to have said that all black people wanted was "comfortable shoes, good sex and a warm place to go to the bathroom." Doesn't quite have the same impact as "loose shoes, tight pussy and a warm place to shit," which is what Butz actually said.

There was something about that silly, childish report in Colorado that epitomized the whole sorry state of local TV news, where euphemism seems the natural mode of expression. Apart from some extended footage from the same CBS Denver affiliate tracking the progress of funnel clouds touching down in the area -- a story that could not be shaped or spun because it was being covered as it was happening -- nearly everything I watched gave off a sense of unreality. The imprecision of language just came to seem the most obvious aspect of broadcasting that implied what we saw and heard was a managed spectacle, a tidied-up representation of real events.

Record covers used to come with small-print instructions along the spine: "File under easy listening" or "File under pop/rock: The Beatles" and so on. Almost every story I watched on every local news station felt as though it had come to the anchors and reporters with similar instructions. Each story was categorized and predigested before it was presented to viewers -- all ambiguity and uncertainty was removed. Caterina Bandini at WHDH Boston introducing a story with "The commission investigating the 9/11 attacks shared with the nation today what it has learned about the original plans [dramatic pause] and the details are chilling," doesn't feel like someone telling you that al-Qaida wanted to fly planes into nuclear power plants and locations on the West Coast. She sounded as if she was making a pitch for a miniseries you'd never want to watch. Instead of trying to give credence to the unthinkable, she's content to treat it as if it were unthinkable, and thus impossible.

The standard bleat about television news is that it has become entertainment, and that the audience is too inured by exposure to the media to know the difference between entertainment and reality anyway (a snob's argument that depends on viewing most people as morons). It seems much more insidious than that. Anchors and reporters seem like the ones with no sense of the reality of the events they talk about. They don't try to communicate the meanings and consequences of the stories they report. Instead they try to make them recognizable as things that have happened before -- Accident Takes Innocent Lives; Trouble in the Middle East; Crime Shocks Quiet Neighborhood -- and will happen again.

For years movies and TV shows dramatized breaking news stories with shots of newspapers spinning toward the camera and stopping to reveal screaming headlines in block print. After that there'd be a cut to a capped newsboy crying "Extry! Extry!" as people crowded in to get a copy of the latest edition for themselves. The 24-hour news cycle and its chief henchmen, cable TV and the Web, have obliterated that sense of urgency. Or rather, since that sense of urgency is now the norm, they have made it irrelevant. If everything is dire, then nothing is, and the overall effect is to make reality itself unreal. At no point in what I watched did anyone manage to make the dots come alive, at no point was anyone on-screen able to talk like a human being and say, "This is really happening."

Shares