I was standing at the intersection of Sixth Avenue and Pine Street in Seattle, the quarry of two linked rows of wool-capped protesters. Some of them were dressed as giant ears of corn; I wore a Banana Republic rayon skirt and Enzo Angiolini Mary Janes -- all in black. I carried a briefcase with an ID tag that brightly declared me a United States delegate to the World Trade Organization Ministerial. I was the living, breathing subject of all these capped kids' ire, and they had me cornered.

My thoughts, as I nervously realized that I was not going to be able to exit this intersection without some kind of confrontation, were not about world trade, or the environment, or about how I was going to get to the meetings I was scheduled to attend. My thought, instead, was this: What kind of shitty mother am I to let myself get into a jam like this?

I work for the U.S. Department of the Interior because of a deep and hard-

wired love of nature. I spent my childhood summers near the tidal bays of New Jersey, where my mother and father taught me celestial navigation and

drop-lining for blue-claw crabs. I was the New Jersey press secretary for Bill Clinton's 1992 presidential campaign, having joined the effort because I was appalled by what the Bush administration was doing to clean-air regulations. I came to Washington to work for Bruce Babbitt, the secretary of the interior, partly because he was a card-carrying member of the League of Conservation Voters.

True, the Interior Department hasn't always had much to do with world trade. But now, with the satellite-quick speed of globalization, we have to make sure that migratory birds, endangered butterflies, national parks and the people who love them are represented at these trade negotiations. So I was dispatched as the leader of a lonely delegation of two, to begin our department's nascent presence in WTO trade talks.

This was only the third time in four years that I had been away from home for more than one night. I've got two curly-headed babies there, one recently emergent from toddlerhood, one just about to dive in. There has to be a pretty good reason for me to leave them: a romantic anniversary weekend away with my husband, for example; increased globalization of world trade, for another.

I've always liked how my work on the environment is another way of

taking care of my kids. I wipe their noses; I chop broccoli into microscopic

pieces and hide it in macaroni and cheese; I push for a permanent source of

funding to purchase more parks and wildlife refuges. All in a day's work.

But these threads of my life got somewhat tangled in the streets of Seattle.

Shortly before 7 a.m. I walked to the Westin Hotel, where the U.S. delegation held its morning briefing for members. Afterward, several of us walked across the street to a Starbucks (I know, I know) and sat down with coffee and food. Soon after, the capped boys ran past, pounding the windows of the coffee shop and spattering the door with lapis-colored paintballs. One opened the doors and yelled inside. " Join the people, goddamn it!"

I was slightly stunned. I agreed with these people: There needs to be

more openness in the proceedings; there needs to be more care taken with

protection of the environment. That's why I came here -- to change the rules. I have, after all, been speaking for the trees for a while now. I've even got a environmentalist husband who favors tactics similar to those erupting around me. But here I was, for all the world just another suit sipping rain-forest-destroying coffee before meetings with global-trade puppeteers.

We left the Starbucks and walked back to the Westin Hotel. It was locked.

Scared-looking police blocked the entrances. A white-haired man pounded on the glass, yelling, "I am an undersecretary with the United States Government and there are negotiations going on that I must attend!" The police would not let him in. We found an elevator in the parking garage and rode up and down for a while, but couldn't find a way into the hotel.

About this time, I felt the animal instinct kick in. It's a familiar reflex for a

mother, but not one I often feel walking, child-free, in the middle of the day in the glittering downtown of an American city. Yet, as the streets deteriorated, my peripheral vision lengthened and my muscles slightly tensed, preparing to spring out of harms way. What animal was I? In this case, one that was being hunted, one that was wished extinct.

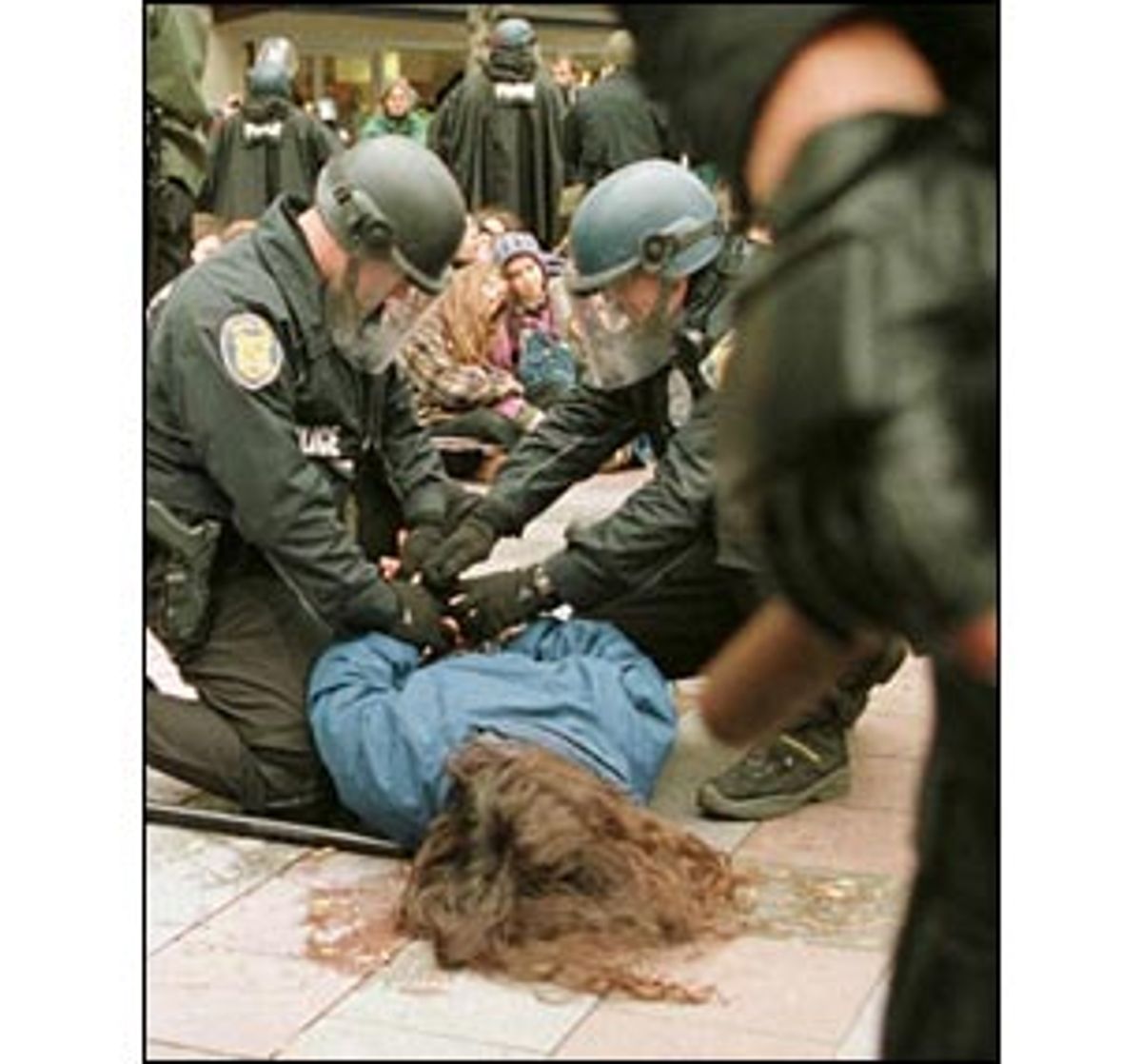

A clump of colleagues and I changed strategy -- from trying to get to a particular place to trying to get to any place that was inside and secure. Instead we got trapped between two linked and locked lines of protestors at the intersection of Sixth and Pine. Suddenly it was just us and many, many people who hated us for being there and didn't want to let us leave. We were cornered by the pack, conflicted about the issues -- caught in every way imaginable.

All mothers learn to expect the unexpected. That's why we all carry huge bags full of seemingly useless items which, employed creatively, become essential in the crisis of the moment. But I was off duty. The only thing I had in my bag at Sixth and Pine was a briefing book on trade and the environment. I doubted the protesters surrounding me would find the book essential in this particular crisis. If anything, the document could be used as evidence of my "guilt."

So I stood there and thought: "This is incredibly irresponsible. I have two little children at home and I am now standing in the middle of a street where literally anything could happen to me." Increased globalization is simply not a good enough reason to put my kids in that kind of jeopardy.

Then something unexpected happened. A young woman in an orange cap appeared next to me and my two colleagues. She said softly, "If you want to get out, you need to go over there," and nodded toward the upper left corner of the human chain that boxed us in. We walked to that corner, looking for a break. Two women there unlinked their hands for us to pass. A boy nearby shouted, "Don't let them go!" and the women whispered, "Hurry through!" And we did. A small, sweet moment of kindness in a chaotic day.

I have always believed that the most important local action a person can take is to assume responsibility for her own family, to make sure they have what they need to be safe and happy: shelter, food, laughter, clean air and water. Places to play.

But sometimes you can do everything right at home and then, if you are distracted by the peace, something larger will come along that undoes all your careful planning. It could be an unexpected flu, or a fender bender; or it could be a trade agreement that didn't have an environmental review process. Each event can have a profound impact, each event encroaches on our quality of life, and so we are caught, all of us, in the same intersection, between global and local.

For our kids' sake we need a constructive confrontation. We cannot allow thinking globally to be hurtful locally, to interfere with our own ability to take care of our families. That is what the nonviolent protesters are saying in Seattle, and I believe our country is listening. I believe that our president is listening, and he agrees.

Shares