Christine (not her real name) remembers the day she lost her little brother.

She was 7 and he was 4. They had grown up close. Their mother was an alcoholic and a drug user, their father bedridden with emphysema, so they spent most of their time together, running around the apartment complex where they lived, Christine taking care, leading the way.

"My mom didn't know how to take care of us," Christine, now 22, recalls. "He attached himself to me because I showed him that I cared about him.

"He looked up to me and we always used to do things together. He would follow me around and go places with me, and I'd be watching him. I would always buy him toys and candy and tell him that I loved him. I remember playing with him all the time."

That day Christine was at a neighbor's apartment. She saw a police car drive by, and the next thing she knew, her mother was being arrested and Christine was being driven away in a separate car.

"I was so small," says Christine. "I just thought, OK, my mother's getting arrested. She's gonna come back and I'll probably live with my aunt and uncle until my mother gets well.

"But I never did come back."

Christine saw her brother a few times during the first confusing months in foster care. But then the visits stopped abruptly. At the time, Christine did not understand why. Later she learned from social workers that her brother had been adopted by a family that did not want him to have contact with "outside family members."

When her brother was 10 years old, Christine was allowed a single visit. "I always worried about him, I always thought about him all the time," Christine says. "I still do. But he hardly remembered me at all. He acted like he was [his adoptive parents'] child from birth and didn't know who I was."

Christine -- who went on to grow up in a series of foster homes, group homes and juvenile halls -- wound up feeling as if she were being punished for her mother's mistakes. "I was not part of what my mother did -- neglecting both of us," she says. "I understand that the mother gets singled out because she was neglecting, but to not let brothers and sisters be in contact doesn't make sense to me.

"We were innocent, we didn't do anything, and I don't think it's right for us not to see each other."

In the legal labyrinth set up to deal with disintegrating families, it is common to hear talk of a child's "best interests." They -- the best interests of a child, that is -- are considered when a court decides whether to permanently separate a parent and child. The judge has a legal obligation to question whether the risk of further abuse or neglect outweighs the benefits of the familial bond. In fact, parents have a constitutional right to be with their children unless proved unfit to care for them.

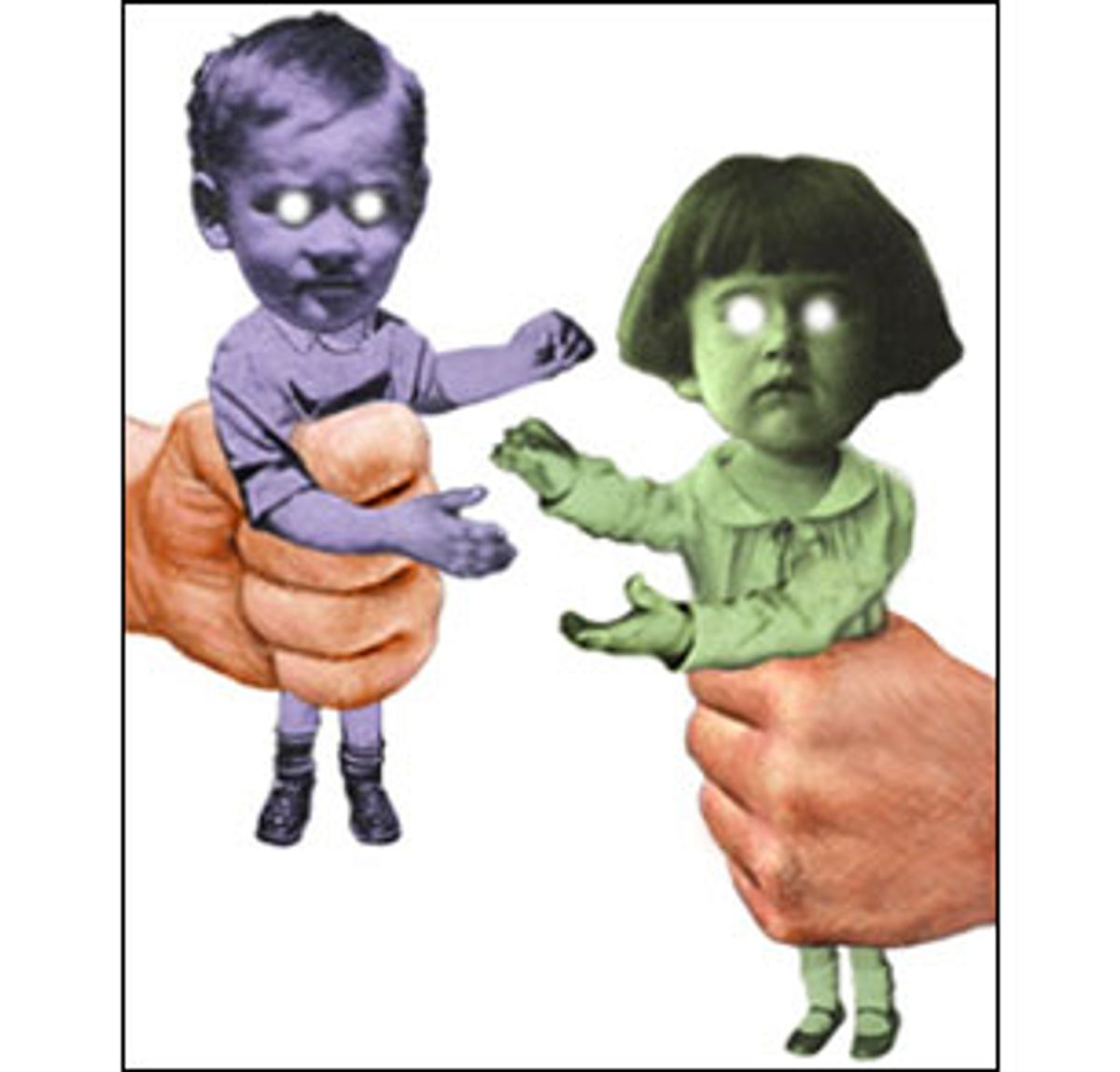

To divide siblings -- to send brothers and sisters in different directions without any explanation or a means to meet again -- doesn't require the same "clear and convincing evidence" that a bond must be severed. An abusive or neglectful parent actually has greater rights before the court to hold on to his or her children than those children have to remain with each other. Those who decide where children will go and with whom they remain are guided, for the most part, by necessity. They must focus on a child's prospects for adoption at a time when the demand, such as it is, is for lone children -- the younger, the better.

It's not that social workers don't try to keep sibings together, says Lillian Johnson, who was director of San Francisco's child welfare department for 10 years. They do. "But it's very quick and dirty, because the likelihood of finding a family that will take more than two children is so limited that pretty soon they start looking at, 'Which two kids should we keep together -- the oldest, the youngest, the middle ones? Should the oldest stay with youngest?'

"It ends up being rather arbitrary. Sometimes all they have are families that only want one child."

Social workers see it happen all the time. But no one keeps track of sibling separations and little research exists on their impact. Some small studies, which do not look at the nation as a whole, indicate that between 25 and 75 percent of foster children get separated from their brothers and sisters.

The psychic wounds of those separations, very often involving children who have functioned as parents to their little brothers and sisters and for whom sibling connections are the last vestiges of family that they have, run deep. Child welfare professionals see the emotional fallout but say they are hard-pressed to do anything about it.

The number of children in foster care has ballooned to more than 500,000 while the number of foster home beds has shrunk. And new federal legislation -- the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (ASFA) -- has created pressure (and financial incentives) to get children into permanent homes as quickly as possible.

"I like adoption, I believe in adoption; lots of children are appropriately and well adopted," says Johnson, who now heads the Kinship Support Network at San Francisco's Edgewood Center for Children and Families. "But ASFA is stripping families.

"Say we have a sibling group and Mama has a new baby. The brother and sister are 6 and 8. The new baby is going to get adopted, and lose his brothers and sisters."

There is no legal guarantee that the brother and sister will know where the new baby has gone or be told why they can't be together. And they may be lost to the new baby, whose adoptive parents may not reveal the existence or whereabouts of siblings.

"I don't know what happened," speculates Christine about her own separation. "I guess they didn't want me to get adopted or I was just too old."

Attempts to establish a constitutional right for children to stay together have been valiant, but futile. Boston attorney Susan Dillard argued for such a right when she represented a 4-year-old boy in a case that ended a year ago. Hugo and his 6-year-old sister, Gloria (not their real names), had been in the same foster home since Hugo was 9 months old. Gloria was adopted by their foster mother, who also wanted to adopt Hugo. Instead, the Massachusetts courts gave custody of Hugo to an aunt in New Jersey.

Dillard asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear Hugo's case. She argued that the sibling bond is protected by the 14th Amendment, which forbids any law denying "life, liberty or property" without due process. It is the same amendment that protects the relationship between parent and child.

Hugo and Gloria never got their day in court. The Supreme Court declined the case without comment, and Hugo was shipped to New Jersey. More recently, the justices did take on the now-familiar Troxel case, which questions whether grandparents have a legal right to visits with their grandchildren.

Grown-ups, apparently, have greater protection under the law.

"We're a very adult-focused society," observes Madelyn Freundlich, executive director of the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, who consulted with Dillard on Hugo's case. "Litigation comes down to the rights of adults and figuring out who has the greatest rights in a particular case.

"In Hugo and Gloria's case, it came down to the respective rights of the foster parent and the biological relative [the aunt]. The sibling relationship is relegated to a lower level of analysis," she adds. But "if we recognize the sibling relationship as a very powerful one, as important as other family relationships, it seems natural to try to sustain it at the highest possible level."

Dillard, who has stayed in touch with Gloria, says the separation has taken a toll. "Gloria was very much a big sister and helped Hugo negotiate the world," she says. "She has had a very hard time [since he left]."

Recently, Dillard says, another foster child who was living with Gloria and her foster mother was moved out. "How come every time I have a brother he gets taken from me?" Gloria asked.

Last April in New York, a 12-year-old girl and her 5-year-old brother slipped away from a foster home in the middle of the night -- the boy on the girl's back -- after social workers started talking about separating them. With the assistance of their mother, whose alleged neglect was the reason for their placement in foster care, they fled to the airport and got to Guatemala, where they live, as fugitives, with relatives. They miss their mother, the girl has told reporters, but cannot go back to visit her for fear of being picked up by the police, sent back to foster care and separated from each other.

"These are sustaining ties," says Barbara Nordhaus, coordinator of child placement and custody at the Yale Child Study Center. "When the system takes a significant and deeply connected sibling relationship and irreparably destroys it, it is a further act of cruelty, a further psychological assault" on a child who has already experienced the loss of parents, home and community.

The children who do manage to remain with their siblings throughout their years in foster care, says Nordhaus, often say that "what saved them was that they had each other. They could cry together under the covers, remember Mom and Dad. There was a sense of not being alone in the world, not being quite so stripped of absolutely everything."

Losing a brother or sister is especially painful for children who come from fragile families where the sibling bond may be the strongest one they have. When parents are gone or incapacitated by drugs, older siblings often step into the breach, caring and looking out for the little ones. If those siblings are later separated, the older ones may see it as their own failure.

One man, now in his 20s, spent his early childhood taking care of several younger brothers and sisters, until Child Protective Services stepped in and broke them up, putting them in separate placements. "I asked for help in finding them," he recalls, "but when it seemed like I was close to locating them, all help disappeared. I kept wondering, were my brothers and sisters going through the same things as me, or worse?

"I'm the oldest and I wasn't there for them."

And yet, according to Kathy Barbell, director of foster care for the Child Welfare League of America, some social workers will intentionally separate siblings in the belief that the older child deserves a chance to "be a child again" without worrying about the younger ones.

It is true, says Nordhaus, that caring for a younger sibling is a heavy burden for a child, but separation is no way to lift it. "If anything goes wrong in the lives of their charges," she says, older siblings often "blame themselves and feel responsible. It can have a devastating impact. When they feel they must save their siblings and they can't, it further compounds their sense of utter helplessness."

The loss of a sibling bond also can make it hard for children to form lasting relationships later on. "Every time a child loses a tie to an important figure, there is a risk that the child's ability to make attachments, to trust, will be jeopardized," says Nordhaus.

Ida, now in her late 20s, grew up in group and foster homes from the age of 7. "Me and my sister were separated when we got put in the system," she says, "so the family bond is not there. On a personal level, you become very analytical. You push people to find out what makes them tick. You ask yourself, 'What's the worst thing he can do if he gets mad?' You push, you test, you want to know right away if you're going to be betrayed."

Sayyadina, 19, lost touch with most of her siblings -- two brothers and four sisters -- after they were scattered at a young age among various foster and adoptive homes. Because Sayyadina's younger sister was adopted by a friend of the family's, Sayyadina was able to keep track of her over the years. She says she "makes an effort now to keep in contact. The others I didn't have much relationship with past toddler age because they were adopted into families that chose to be reclusive.

"They're people I think about, but they're not close to me," Sayyadina says. "I don't see them; they don't see me. I don't come around; they don't come around. I figure they're probably pretty lonely because they have no blood relations, and they weren't born into the family they live in."

Tiffany, 22, had a different experience. She and her three younger sisters were placed in an unusual group home that accommodated sibling groups. While they did not get the permanence of an adoptive home, they found another kind of security in their ongoing connection to one another.

"People would ask us why we were so emotionally stable," Tiffany recalls. "We always had each other's backs. 'The sisters' -- that's what they called us. People who didn't have their sisters or brothers with them always had more problems than the rest of us. They really didn't have anybody that they could talk to about what was going on with them."

When social workers started talking about adoption for the youngest sister, the girls objected. "If she had been adopted, that would have screwed up my family," Tiffany explains, "because now we are a family.

"When I think about adoption I think about my siblings more than parents for some reason. They're in the same age range, they look at things the same way I do, they were my support. I guess it comes down to morals, to what you feel is important, and for me blood is very important. I always felt like I deserved some kind of tie to my sisters."

For now, there is little room to consider what a child feels she may deserve as she limps through the child welfare system, already without her parents and likely to lose her brothers and sisters. Johnson believes that the ASFA, with its accelerated timetables for termination of parental rights and financial incentives to get more foster children adopted, has made siblings even more vulnerable to permanent separation.

Attorney Dillard, who heads a panel of lawyers in Boston that takes child custody cases, is waiting for a chance to win legal protection of the sibling bond. She and her colleagues are looking for another sibling case, and this time, she plans to challenge the separation right away, at the moment the children enter foster care, when they may be placed separately if there are not enough beds available in a single home.

"There should be litigation right at the beginning," Dillard explains. "The child's attorney should say, 'I want the department of social services to place the children together so that their family relationship is maintained.'

"It's not enough that they have separated the kids for administrative convenience. There should be an obligation on the state to prove by clear and convincing evidence that the children's right to family integrity should be dissolved."

If the right to family integrity is extended to children, it is possible that children will have a rare opportunity to describe their own "best interests." Their feelings -- their instincts -- are not likely to surprise anyone, even adults unfamiliar with the burdens of poverty or domestic disaster.

"Look at your own family," Johnson suggests. "As you grow older, you lose your parents and what you have left are your siblings. If you're stripped of that, you really are alone."

Shares