This time last year, my happy, friendly seventh-grade daughter was voted off the island. The stars aligned, the dice rolled, the ballots were cast and she was "it." She went from being a member of the "in crowd" to becoming its designated exile. She was talked about, hated, despised, not invited, ridiculed but mostly, most cruelly, ignored.

"I don't exist," she explained to me softly.

"Why?" I yelled to the heavens. "Why you? Why me, the mother of you? What have we done?"

I found out about the smear campaign when I read a batch of saved e-mails my daughter left open on the family computer. She'd never done that before, so I figured she wanted me to read them. She did and I did and it hurt. The electronic missives went beyond mean to breathtakingly evil and they were attached to extensive buddy lists. It seemed that everyone knew about this except me.

I should have known. The phone never rang anymore, my daughter's grades were dropping and she had a hard time getting up in the morning. I constantly asked what was up. Finally, e-mails in hand, I asked again, "Are the girls mad at you?" She stared at me with old, sad eyes and said, "Yes."

What to do? Press for information? Sympathize? Call the mothers? Or do I do what I want to do and murder a bunch of girls for being spiteful adolescents?

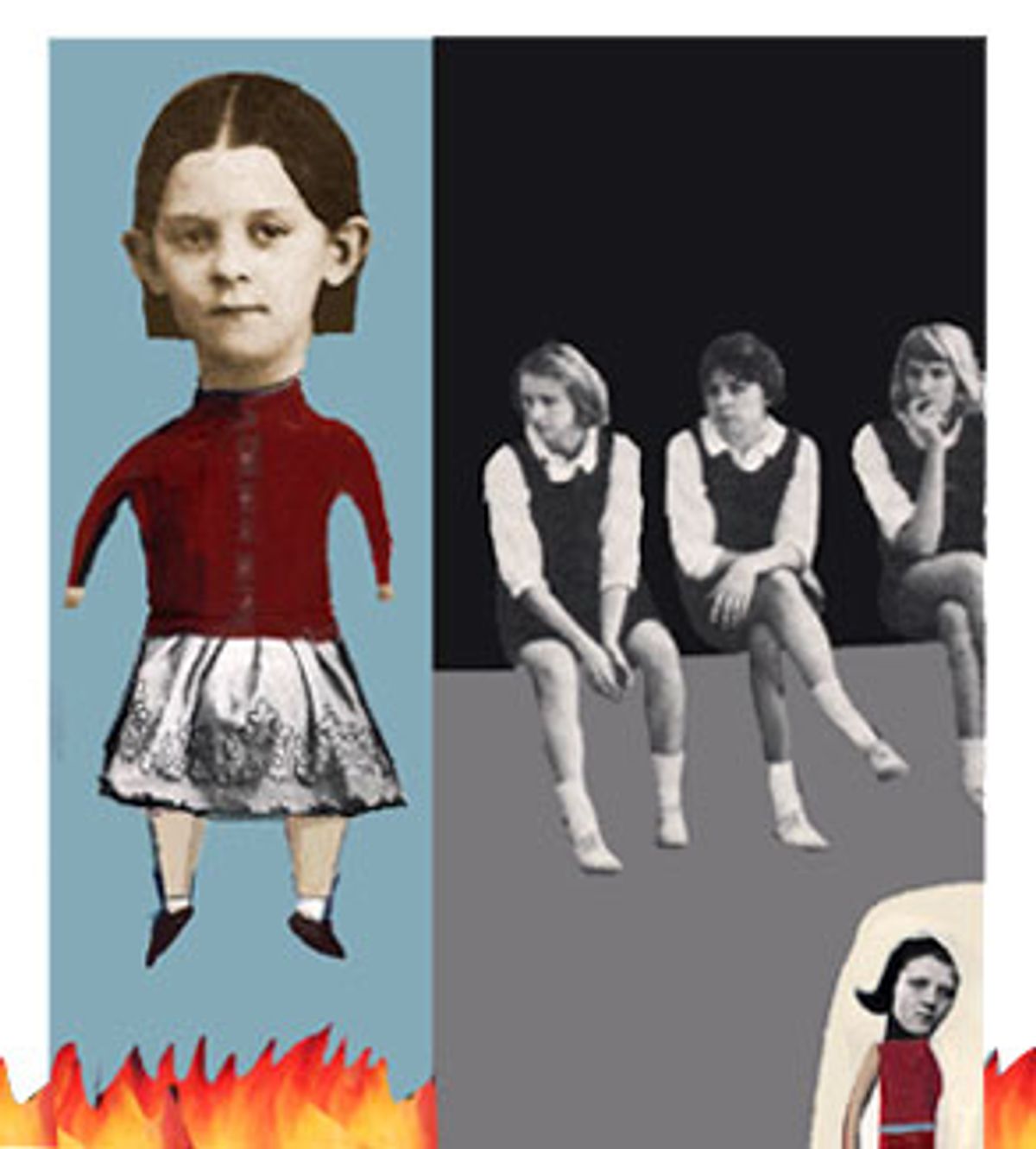

Sound bitter? Well, I was a girl once. I survived -- just barely -- being left out of a chick clique. I know that sisterhood can suck. Plus, I've read Margaret Atwood's "Cat's Eye" and Mary Pipher's "Reviving Ophelia," and I know that raising girls is not for the fainthearted. But even an educated veteran of girlie bullying doesn't think it's going to happen to her daughter. And when it does, she realizes that the only thing to do is hope, pray and stick pins in dolls -- whatever gets you through.

I sought counsel from a wise and crusty high school teacher who advised that I stay out of it, adding, "What doesn't kill her, makes her stronger." OK, but what if it did kill her? It crossed my mind more than once when I couldn't wake my daughter in the morning. My heart racing, I would bend over to feel her morning breath on my cheek until finally her eyes would open and she'd begin telling me all the reasons she couldn't go to school.

The car pool line was the worst part of the day. I would pull up to see my daughter standing alone on the curb, scanning cars with wounded eyes. The rest of the girls huddled a regulation 10 feet behind her. Every time one of them climbed into a car, the rest would wave goodbye, making phone call hand signals and typing motions signifying, "Call me, e-mail me, we'll get right back on it as soon as we get home."

My daughter would walk slowly to our car, a tight smile glued on her face. She'd get in, lock the doors and turn her body toward the window. Then she would cry great gulping sobs of despair and misery and hopelessness. Sometimes, I'd want to laugh, sputtering something like, "Oh baby, if you think this is bad ..." Mostly I'd grip the steering wheel in cold, white rage.

I gave it a month. I promised my daughter that the clique would wear itself out by Thanksgiving. I was wrong. Fueled by e-mail and instant messages, the campaign intensified and the fall semester crept by in excrutiating real time. My daughter's transgressions were never completely defined. She'd beg for explanations: "Am I mean? Am I ugly? Did I say or do something wrong?" But there was never an answer. Her tormentors would roll their eyes and sigh as if to say: "If you don't know, then you are more dense than we thought."

Even the fringe girls, those not quite in the clique, started avoiding my daughter. Under strict orders from the reigning queens to not speak to, look at or, God help you, sit near the victim, they complied until finally, the cheese stood alone.

I find myself in a group of can-do moms, who tend to make things happen -- and stop happening. I've watched them storm into the principal's office demanding different teachers and disputing grades. I've had mothers try to enlist me in various fix-it campaigns, from banning science projects to changing reading programs. I have declined to participate, mostly because I've always been afraid to tempt the fates. So I don't interfere. I never call other mothers or make appointments with principals. I try to stay out of my children's quarrels and petty grievances. I don't believe in fixing science projects any more than I believe in fixing problems. And, while I would have tried anything during this debacle, I didn't want to make things worse.

My husband, meanwhile, couldn't get over it: "Why do they do this?" he demanded again and again. "Because it gives them power, sickening, glorious, intoxicating power over another human being," I would say. "They don't think she's really suffering. They don't imagine her pain. They are just damn glad it's not them and so they participate. They instigate. They fuel the fire, fan the flames and all of it bonds them closer. Sometimes they are sickened by it, their conscience aches and they put themselves in the victim's Nikes. Eventually, they convince themselves she deserves it. And ultimately, they are terrified of becoming the next victim. So, they do what they have to."

I couldn't determine who was the queen. I'd pick one and then it would be another one who was uncommonly cruel that day. I kept thinking it would end. It didn't. I lectured constantly: "When you come out of this, you won't be the same. You will never participate in this kind of thing. You will be stronger, you will be tougher, you will be nicer to those less smart, pretty and talented than you." She'd nod but I know she didn't believe me. Heck, I didn't believe me.

I read up on warning signals of teenage depression. I went into chat rooms where teens poured out their angst and suggested ways to kill themselves. I locked up the booze, threw out prescription medications, made sure she ate, watched to see if she swallowed, followed her to the bathroom. I slowly lost myself. I avoided friends, didn't go to parties and suffered along with her. How long could it last? How long could welast?

I bargained with God. I told him I'd go to church more, pray harder and keep more commandments if he'd take this from her. I blamed myself. I hadn't hosted enough sleepovers. I didn't play tennis with the other mothers. I didn't go out to lunch with the ladies. I worked too much. I wasn't a popular mother.

There were kindnesses along the way. Random phone calls from other mothers. One friend sent a plant with a note saying, "By the time this blooms, it will be over." Childhood friends from the other school in town started dropping by, calling. A track coach asked her to run for the team. A school guidance counselor asked her to volunteer at a crisis center, filing papers and making coffee. I was pitifully grateful for each of them. A truism struck home with staggering force: "You find out who your friends are."

These gestures provided the first rays of light in a long, dark stretch. Volunteer work gave my daughter something to focus on other than her own misery; track made her part of a team. Old friends provided evidence that she was not unlovable.

The holidays arrived and things were less than merry. My daughter didn't get invited to Christmas parties; her name wasn't on any gift swap lists. She stayed close to my side, rarely venturing out. We both thought the spring semester would be better; but just in case, we started talking about switching schools, even though she'd been at this one for less than nine months.

We had made the decision to try private school after sixth grade, mostly because the public middle school was plagued with problems related to overcrowding and discipline. My daughter had lots of friends at the private school; they were in dance together and played softball in the same league. The plan was to enjoy these friendships at school, along with small classes and more athletic opportunities.

And the transfer worked like a charm. My daughter had a tight group of friends upon arrival at the private school -- they picked up where they left off during the summer. But when she was arbitrarily exiled a couple of months into the school year, it occured to me, as I wrote the spring tuition check, that I was paying big bucks for this horror show.

My daughter started spending time with girls from the other school. I started to go out some, see old friends, have dates with my husband. Life started to feel a little more normal, less of an ordeal. My daughter started to lose her black circles and haunted look. I stopped waking in the night. The season of hell began to run its course, like a bad case of the flu. But none of us were unscathed. Not my daughter, not me and not the perps.

Finally, despite the signs of ditente, my daughter decide to quit the private school and go to the public school. The decision gave her something to hold on to, something to negate the feelings of hopelessness. An end was in sight. All of the messy social and economic issues dogging the public schools seemed puny compared to the ugly motives behind the private school freeze-out. I worried briefly that changing schools was a cowardly quick fix, but the decision felt right as soon as we made it.

Strangely, the girls were shocked by my daughter's decision to flee. Prompted by teachers and parents, they tentatively asked her why she was leaving. Nobody thought it had gone as far as it had. My daughter had done the stoic thing -- held her head high and kept her tears in check. Her response to their bizarre expressions of concern was equally calm: "I'm outta here," she said. "I'm leaving you to torture each other."

A year later, my daughter's life is entirely different. She is happy and busy with friends, school work and activities. One of the former torturers is now being tortured. She calls my daughter and cries mournfully. I watch, fascinated, as my daughter murmurs sympathy, invites this onetime foe to spend the night, offers her a shoulder to cry on. How can she forgive so easily? Or was forgiveness the most valuable lesson? Perhaps, like the teacher so strangely predicted, it ends up being a good thing, something that makes her tougher, better, stronger in the long run.

I know I'm different. Not tougher, not stronger but changed somehow. It has finally sunk in. There is no immunization against hurt. There is no protection against cruelty. For all the things I can do for her, saving my daughter from life's hard twists is not one of them. Tough lesson all the way around.

Furthermore, if it's really the worst thing that ever happens to her, she'll indeed be lucky.

Shares