In a recent story in the New York Times with the headline "Lawsuits Touch Off Debate Over Paddling in the Schools," I read of children in Zwolle, La., who felt the sting of the paddle and whose parents were now suing. The item brought back some unwelcome memories. Even as a 50-year-old university professor, I could not suppress the anger that welled up inside me reading about something I had wrongly assumed was a relic of the past -- my past.

Twenty-three states, most of them in the South, still allow corporal punishment. The most recent data indicates that some 365,000 students are paddled each year. But I have no wish to write about numbers. It is about one individual child I write and of the invisible scars that paddling leaves behind.

In 1956, I was a first-grader at Belle Stone Elementary School in Canton, Ohio. I was 7 years old. I stood 4 feet tall and weighed all of 52 pounds. I was basically a good kid. Like many back then, I said "Yes, Sir," and "No, Ma'am," when addressed by adults. Teachers brought out in me an equal mixture of respect and fear. The fear would soon overtake the respect.

After reading about the Louisiana lawsuit, I decided to dig out my first grade report card. It was divided into two sections. The first was called "Scholarship," and recorded that I had a mix of B's and C's. The second section was dedicated to "Citizenship." And there, under "Thinks and Works Well Alone," were two check marks -- a record of the charges against me. I had been whispering with my friend Billy Rosenthal in the back of class while the teacher, Mrs. P, was talking.

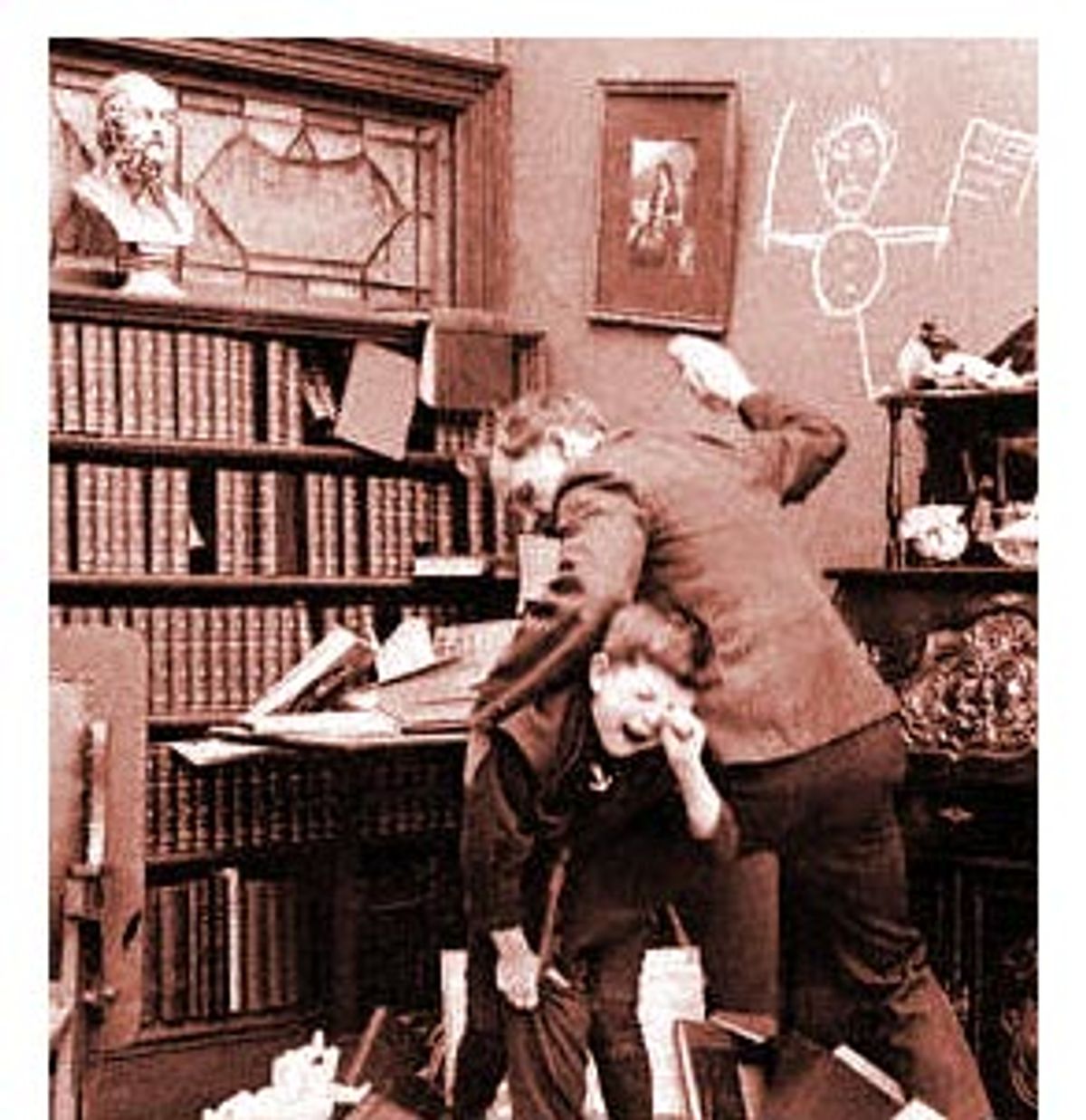

Mrs. P was a large and stern woman who glowered at anyone who did not pay strict attention or who did not sit perfectly still. I was a squirmer. So was Billy. What I remember is this: One day in that first year of school, I was hauled out of class by the scruff of my neck and told to put my hands against the cold ceramic tiles of the wall. Then I was told to spread my feet apart and bend over. In her strong hands, Mrs. P held a 3-foot-long oak paddle with Greek letters on it -- a memento of a college fraternity. That paddle had long hung by a leather thong just outside the principal's office -- a warning to one and all, a symbol of authority, like a Roman fasces.

"I am doing this because I care about you," Mrs. P told me, wrapping the leather thong around the wrist of her right hand. An instant later, I felt the wood slam against my buttocks. I lurched forward into the wall, stiffening my arms to absorb the shock. The crack of the paddle resounded down the hall. I imagine there was not a soul in that school who did not hear it and wince. In later years I associated it with the dimming of the lights when an executioner throws the switch on the electric chair.

Other students and teachers walked by and gawked. I neither cried nor flinched. I took my punishment as I was told I must -- "like a man." I received half a dozen whacks. I remember limping home over the hill, Mrs. P's words still in my ears: "I am doing this because I care about you." I was thinking, "I wish she didn't care so much."

At home I inspected the damage in the privacy of my bedroom. There were red welts on both cheeks. I never said a word to my parents. After that paddling I did not whisper in class again. In fact, I did not speak in class at all. Mostly I tried to be invisible and in this, at least, I succeeded. After the first grade, I was never again paddled, though the threat of it was as much a part of every school day as the recitation of the Lord's Prayer and the Pledge of Allegiance. Scarcely a week went by when the crack of the paddle did not fill the halls.

In the years after, I became a journalist and a teacher. But those few moments in the hallway came to be a defining memory not only of my first year in school but of childhood itself. That early introduction to fear and humiliation was what I remembered first and last. And when I had my own two sons and I felt my hand rise in anger, I remembered again the paddle. Almost always my hand froze in midair. When it did not I was filled with remorse.

Until reading recent news accounts I had thought that mine was the last generation whose elders believed that to "spare the rod" was to "spoil the child." In the intervening years I rarely thought about the paddle. The lesson was ineffective but searing. If it was intended to prove that reason has its limits or that force can legitimately be wielded against even the most vulnerable among us, then it failed utterly. It was a kind of branding iron that marked me for public scorn and private shame.

That such a punishment should be sanctioned for children, long after the stocks, the pillory and cat-o'-nine-tails were banned as inhumane for adults, says something about our culture: It says that we are willing to resort to the primitive when it comes to the defenseless.

Never mind that virtually every industrialized nation except Canada, the U.S. and one state in Australia has outlawed paddling, or that New Jersey banned the practice 134 years ago. Texas, home of self-proclaimed education President George Bush, leads the nation in the number of kids struck each year: 85,000. And lawsuits like that in Louisiana seldom prevail, given the vague wording of state laws and the Supreme Court's finding that such punishment is neither cruel nor unusual.

Some progress has been made. Twenty years ago in my home state of Ohio, the paddle was brought out 65,000 times. Last year it was used 600 times. And in a University of New Hampshire study, based on interviews with 800 mothers, researchers concluded that corporal punishment may curb immediate offending behavior but in the long run -- four years out -- it produced children who were decidedly more rebellious.

I can attest to that. As an adult, I suspect the experience helped engender my smoldering distrust of authority figures and institutions. I am sure that it molded my belief that a school, above all else, should be a sanctuary free of violence, a refuge where the only hand raised should be that of an eager student. It is one of the reasons I became a teacher, having been convinced that there was a better way.

Last year, for the first time in four decades, I returned to Belle Stone Elementary School. My escort was the new principal, Daninel J. Nero. Surprisingly little had changed. The tiles were still cold to the touch; the wrought iron banisters were the same, though the stone steps were worn a little smoother from so many decades of small feet in big hurries.

But what I remembered most as I walked down the long hallway past the door to Mrs. P's class was neither the laughter nor the sense of wonder, but the echo of the paddle informing one and all of my punishment. I asked the principal if the paddle still hung on the office wall. He didn't even know what I was talking about. And that is how it should be.

Shares