My wife arrived home from work the other day to find a well-dressed man with a camera standing in our driveway. He and I had been talking inside for an hour, and when we were done he had said there was one more thing. Could he take a picture out front? Just in case? I said sure, of course.

I hadn't told him in so many words about my problem, but I think he had guessed. He probably saw a lot of people like me: vaguely troubled, beset with inchoate longings, restless, dabbing tentatively at the edge of a wound, flirting with catastrophe and inexplicably willing, out of quixotic hope, blind ignorance or sheer existential discontent, to plunge our household deeper into debt and cast our fate to the title company, to trudge up the hill with all our belongings like refugees in search of a better life or at least a different life, a different set of keys, a different color headache in a different part of town.

It had started with a TV commercial for Housevalue.com.

"Housevalue.com," I said to the poodle. "Look at that: Maybe they'll tell us what this house is worth these days." I logged on and put in my address and ZIP Code and the very next day that real estate guy called. I said, "Come on by, let's talk."

I just wanted to see what the house was worth, that's all.

Maybe they teach real estate guys to be good with dogs or maybe this guy genuinely respected our 80-pound standard poodle's need to put her paws on his charcoal sweater vest and try to lick the 5 o'clock shadow off his face, but in either case his one gesture of kindness toward the dog made me almost willing to let him do what he wanted to do, which as it turned out was to move us out of the house and put us in an apartment, bring in painters, floor finishers and maybe a gardener, paint it, clean it, finish it and sell it out from under us for almost twice what we paid five years ago.

So that's how come he was in the driveway with the camera when the green, wife-bearing RAV-4 clambered up the curb cut. And my wife saw him and looked at me quizzically and said, "You didn't sell the house, did you?" I said no, we were just talking. I was just gathering information. That's how it always starts, I'm gathering information, and next thing you know there's a notary at the door.

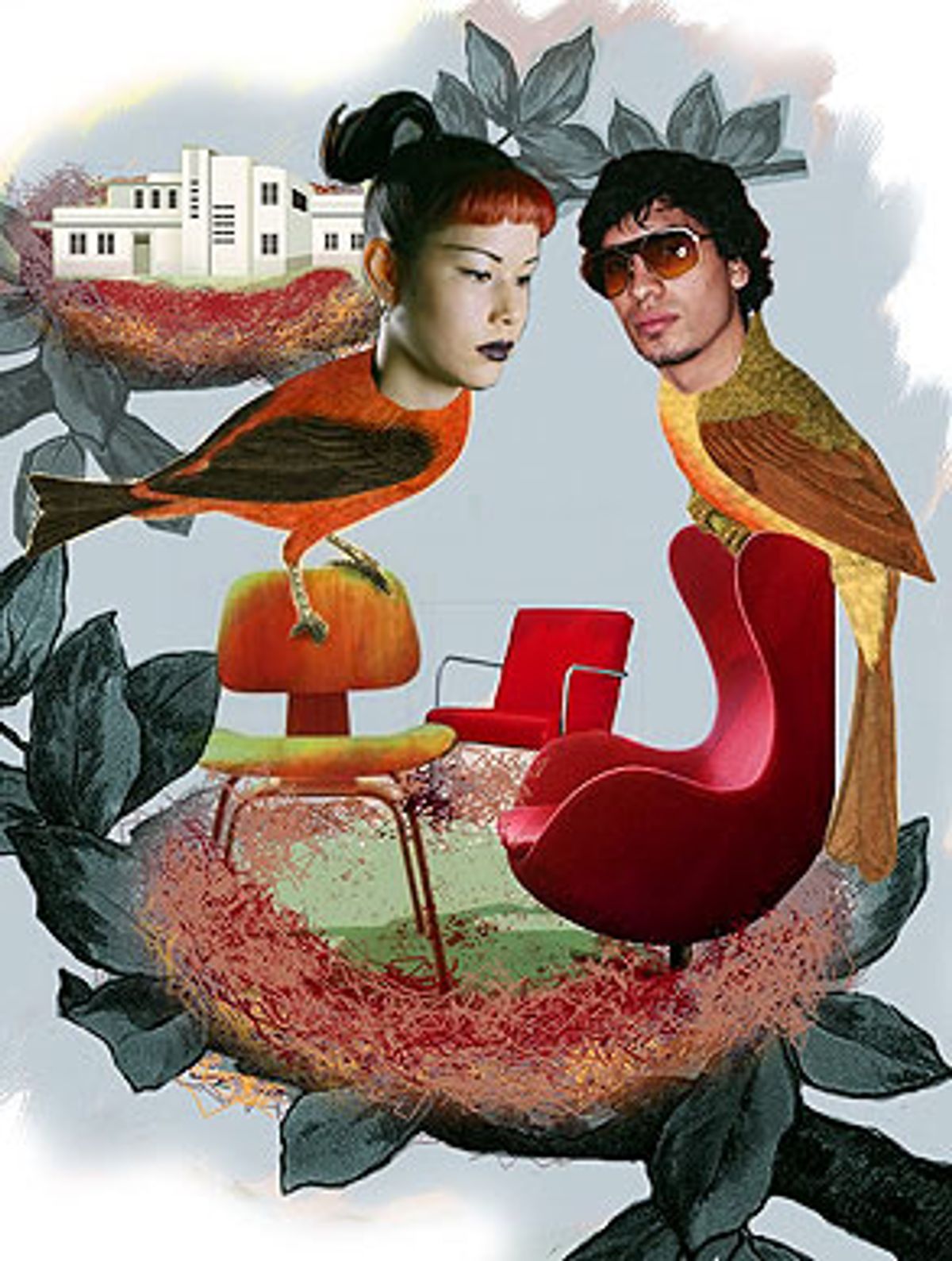

And that's as good a place as any to explain that this is the first of a new occasional series about housing and its discontents. I, the mildly unhinged guy in overalls, shall attempt to explicate the joys and manias that seem to affect anyone who becomes signatory to a real property deed. I will look at my furniture and my drip system, my 110 wiring, my Cat 5E cabling plan, my skylights, my pot rack, my copper pipes, my nasturtiums. I will study the trail of my migratory life through sundry domiciles. I will unburden myself of my lighting obsessions, my sensitivity to drafts, my fervent hope for higher ceilings, my belief that a particular wall should be demolished with sledge hammers this afternoon. I shall consider such matters as why can't I just frigging live in a house like a normal person? Why can't I look out the window without mentally rearranging the trees?

My house and the furnishings in it are a source of much anxious deliberation and passionate self-analysis, because they represent not only a blank canvas on which to design the future but an indelible and scribbled record of the past. They embody the choices I have made, and the choices I have made have not always been good. For instance, we bought our house not in a state of studied calculation but one of near panic and fear. As it turns out, our fear was well founded: Had we waited, prices in our city might well have risen out of our reach.

But had we considered the way we want to live, we might have bought, not where we did -- at the cold, foggy and remote western edge of San Francisco at Ocean Beach -- but in the West Portal neighborhood where we now visit and walk around like dirty-faced children from the poor side of town, gazing at bungalows beyond our means. So although we feel fortunate to have a house, it is but one more act that seems to have sprung too much of desperation.

Likewise, the furniture in this house, rather than representing, piece by piece, the careful realization of a coherent aesthetic, instead reveals a history of random opportunities and snap decisions: that table I bought 13 years ago for $15 from a neighbor who sold it to me cheap because she liked my writing! That table left in an apartment sublet by a friend almost 20 years ago! That couch bought at Macy's for too much money because we needed a couch and it was a couch (plus it was green)! That gray, threadbare corduroy sofabed that a co-worker gave us for free when she married! That stereo pieced together with pieces of other stereos; that VCR that hasn't worked right for years, which we hesitate to replace out of fear that the next one will also not work for years!

This house and all the things in it have come to symbolize the randomness and chaos of life rather than its possibilities for order and conscious design. And because, rather than forge a clear vision and work methodically toward it, I have instead chosen to believe that my house will magically be transformed one day into exactly what I want it to be, I walk around the house refuting the reality of everything I see. I say: That bookcase is not the real bookcase; the real bookcase is of polished maple and reaches to the ceiling and has little lights on the bottom of each shelf that create pleasing accents; the real bookcase has glass doors, and fits snugly on the walls as if it were built into the house from the beginning.

Thus for some time it has been easier to live in a Platonic world in which the physical house is but a mere shadow of the real house than to accept the tedious and mind-numbing task of actually buying furniture and remodeling. But living at war with the house has its own corrosive effect. Battling reality is exhausting. I am wearied by the voice that runs in my head like a tour guide in a second-rate museum: This is not the actual chair, but a replica; the real chair is being restored in Athens, Greece; this is not the actual sarcophagus of the queen but a replica; the real one resides in Cairo. So I am faced with unearthing my own history, in order to face the future, to make the choices I must now make consciously, deliberately, in the service of a vision.

One problem with forging a central vision of how the house should be is that I am not simply one man but at least two. There is the man who would flee the city with his lover and build her a castle, who seeks the romantic vision of the cottage by the sea. And there is the man who would live in the bowels of the city as a rebel, the hardbitten hipster whose house reflects his ideas, his loftiness, his intransigence. There is the poet, who would a house of clay and wattles make. And there is the Underground Man, who would a basement flat squat, who would a burger wrapper crumple, who would a late-night party throw, and not invite you.

There is another dialectic as well, between the writer and the craftsman: I sometimes feel like Arthur Rimbaud riding in the bed of a pickup, drunkenly waving a Sawzall, shouting "La bas! La bas!"

But, at bottom, who cares? Why should a house be anything more than a place to keep the rain off? Why, particularly for those of us whose primary work is abstract and cultural, are we investing so much significance in these boxes we sleep in? To what degree is concern with the aesthetics of home a bourgeois distraction, and to what degree is it a deep, historical and cultural duty that connects us with the world and makes us human? Should I simply ignore that cranky Puritan voice that says sensual pleasure, domestic comfort and happiness are somehow cheap, shallow and vulgar? Or is there some truth in it? Am I puttering about the garden solely because I am growing old and soft and bourgeois?

Those are questions that want answering. There also are stories that want telling: how we bought this house, and the gravestone we found in the backyard and all the letters in the attic, and how it has become an unexpected obsession and a strange gift, an object of passion and frustration, a wall to beat our heads against and a wall to slump against in exhaustion.

I want to tell you about the house my grandmother bought that my father inherited, and decided to sell with my brother still living in it. And the house my mother and I built with our own two hands way up there on Bear Mountain in Virginia, off the grid, in the trees. And all the houses we have lived in and loved and miss and wish we could go back to, and their smells and sounds and curtains. There are a lot of houses and a lot of stories about houses.

And then there is the how-to: how to replace a sink drain, fix a faucet, connect a gas stove, install a phone jack, wire a house for Ethernet, replace that old knob-and-tube stuff with grounded Romex, put in a drip system, add an outdoor faucet. The how-to books will tell you how. But they will not tell you all the ways trying to fix a sink drain can push your placid soul to the brink of madness.

I am interested in why, after spending 10 minutes under the sink staring up at the trap, one feels like crying. I am interested in why a grown man, after rewiring one electric light switch, should want to run out of the house exclaiming "Eureka!" like Archimedes. I am interested in discussing the ways I, an ignorant writer, have come to appreciate and emulate the hard, demanding patience of the plumber, have learned to tolerate the physical tedium that must be the soul of the tradesman's life.

I am interested in why I am so interested. I am not an architect or a builder or a businessman. I am not so deluded about the sources of human happiness as to believe even for an instant that finding a new house, moving into it and equipping it to accommodate our slovenly, chaotic and wanton lives will bring us anything but a bigger, more expensive source of complaint and worry.

So is there something wrong with our brains that we would even imagine doing such a thing? Is the homing instinct just too powerful a force to resist? Was there any shred of rational thought behind our sitting in the realtor's office on West Portal on a recent Saturday afternoon thumbing through the bound color booklet he had prepared that explained the fair market value of our current house? And wasn't it interesting how we emerged from that experience determined not to sell but to stay here, as though awakening from the influence of some drug?

And so I have undertaken this investigation not only of the art and business of housing but of my own inner architecture, my will to power over space, my lust for a sculpted interior. I am buying Architectural Record and reading "A Pattern Language." I am tearing down the ceiling with a crowbar. I am losing control. Oh! Blessed rage for order, pale Ramon.

Shares