Since filming of the movie "Gang Tapes" ended, four of its five stars have landed in trouble with the law, primarily for armed robbery. Another cast member couldn't make it to the premiere because he was in jail. Two more actors had friends and relatives who were murdered while the film was being made.

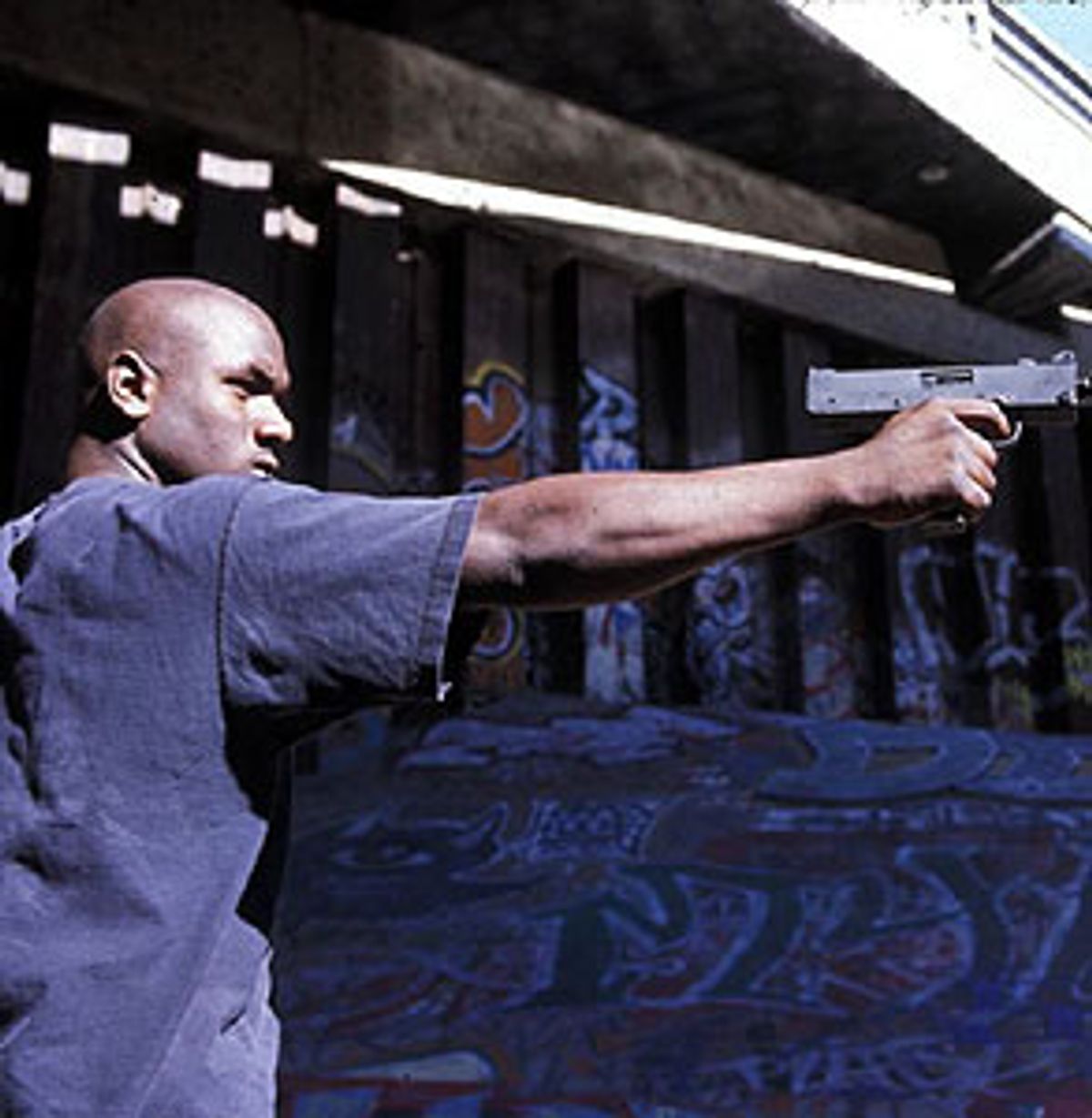

That may seem like an astonishing streak of bad luck for one movie; but given the circumstances of the casting and filming of "Gang Tapes," the outcome is sadly typical. Shot entirely on digital video, "Gang Tapes" is the story of a group of South Central Los Angeles gang members, one of whom videotapes their activities over the course of one summer. The camera bobs and weaves around the gang as they rape, rob and deal crack, leaving a wide swath of death and devastation in their wake. Directed by a Los Angeles Police Department reserve officer, the film featured a cast of mostly novice actors and local gang members who improvised action and dialogue using their own experience as a resource. What resulted is a disturbing depiction of inner-city gang life -- a fictional film that feels as real as a documentary.

"Gang Tapes" is so authentic, say its makers, that movie theaters are shying away from it, leaving what some perceive to be an invitation to violence unscreened by the general public. The film was funded by Lions Gate, a studio with a solid track record at the box office, and it's been endorsed by many in the black community -- garnering kudos from the likes of hip-hop maven Dr. Dre. But more than a decade after the rise of urban-themed breakout films like "Boyz N the Hood" and "Menace II Society" -- even as films like "Brown Sugar" and "Barbershop" perform soundly at the box office -- the threat of mayhem sparked by "Gang Tapes" and its gritty realism appears to have theater owners running the other way. It's been a year since the movie made its debut at film festivals, and it seems destined to be released straight to DVD.

"I can't help but feel that if my film was about Italian kids in the streets of New York, but otherwise the same exact film, this problem wouldn't exist," says "Gang Tapes" director Adam Ripp. "There is a certain amount of racism connected with black films."

Ray Price, the vice president of marketing at Landmark Theaters, acknowledges the stereotypes about black films and black audiences. But he suggests that the fiscal realities affecting most edgy low-budget films also come into play.

"There are a lot of preconceived notions still. It's better than it was, but for those people who are really trying to stretch and enlarge the scope of what [black films] can be, it's a very hard job" to get distribution.

"Gang Tapes" tells the story of Kris, a 14-year-old living with his mother and little sister in Watts. Kris has acquired a video camera from older neighborhood buddies who stole it during a carjacking, and he decides to document all the illicit activities he embarks on with his friends. What unfolds, from Kris' point of view, is the day-to-day life of a crew of Los Angeles gangbangers. The audience, through Kris' lens, sees drive-by shootings, backyard parties, makeshift crack labs and freestyle rap sessions as well as a brutally graphic armed robbery and rape. Eventually, as Kris' friends -- mostly jail-hardened older teenagers -- trigger a gang war with their rivals, the bodies start falling.

"I wanted to make the most realistic film ever made about South Central gang life," Ripp says. "Pull-no-punches raw reality. Brutal. A true depiction of gang members that humanizes them in a way, rather than stereotypes them."

To achieve this goal -- and partly, no doubt, because of a tight $500,000 budget -- Ripp cast his film with Watts locals: gang members, ex-gang members, and friends of gang members. Rather than script the film word for word, he gave his actors script guides and then let them make up their own dialogue. Thanks to the rapid-fire delivery of local slang by the film's actors, as well as the intentionally amateurish camerawork, "Gang Tapes" feels at moments more like a grimly violent documentary than a feature film. It can also be murky and hard to follow, leaving viewers in the dust, wishing for subtitles.

Ripp grew up in Hollywood but got many of his ideas for "Gang Tapes" on the job in Los Angeles: He signed up as a reserve police officer in the late 1990s to research a movie about beat cops and has worked part time as an officer ever since. His cast members were never informed of his other job, even as they gave him insights into the gang world they came from.

"Just like how certain people are prejudiced and racist against black people, a great majority of the community of South Central believes that all police are bad," says Ripp, who believes he was justified in withholding facts from his cast. "I knew it would be hard to convince them a white filmmaker could do this film, let alone a white filmmaker that also happens to be a police officer."

Ripp says he received abundant support from both his cast members and Watts community leaders, one of whom became the executive producer of his film. (Most still do not know about his police work.) With their help, he shot his film in just 12 days during the summer of 2000, as a gang war raged nearby. Several times, locations had to be changed because of gang violence. (Ripp counted 30 shootings during the course of filming.)

When "Gang Tapes" hit the film festivals last summer -- including the Pan-African Film Festival in Watts, San Francisco's Black Film Festival and the New York Underground Film Festival -- it got good reviews from a wide range of critics -- from gang members (Crips and Bloods, Ripp says) who showed up for local screenings, to Elvis Mitchell of the New York Times.

And then Ripp hit a brick wall. Despite the sold-out festival screenings and positive reviews, no one -- not theater owners, not even the studio that financed him -- seemed interested in helping him get widespread theater distribution. Worse, he said, everyone blamed the lack of enthusiasm not on the quality of the film itself but on its content: It was urban, violent and destined to draw black audiences whose reactions distributors feared.

"Every major theater chain in the United States has refused to play 'Gang Tapes,'" says Ripp. "They are fearful that the film will lead to an outbreak of violence in theaters. It is a purely racist perception that films depicting African-American gang members will cause violence in the theaters playing them."

Ripp believes that "Gang Tapes" is so edgy that it's a difficult film even for art houses. But the possibility that the director is reluctant to consider -- that the film is simply not very good -- is one that comes up in discussions with movie industry veterans.

"Something like 'Gang Tapes' may be having difficulty with distribution, but I would submit it's not because of the race of the cast; I think that's just a tough movie to sell. It's not 'Brown Sugar' or 'Barbershop,'" says Sam Kitt, president of 40 Acres and a Mule, Spike Lee's production company. "It's very easy to blame the powers that be, the white man, blah blah, and that's frequently true; but for filmmakers in my experience, frankly, it's never the film, it's always some outside thing."

Still, even if that's the case here, even if "Gang Tapes" is inferior, there is a long history of similar urban films that have had distribution difficulties. Edgy films of all genres may have a hard time finding funding and distribution, but edgy films about African-Americans encounter even more stereotypes and preconceptions. The hurdles for these films are put up not just by skittish theater owners fearful of the "wrong crowd," but also by studios who see no financial advantage in screening a movie that deviates from the profitable norm.

Take the case of "Way Past Cool," an independent film based on Jess Mowry's popular novel about gang life in Oakland, whose creators received film-festival awards but couldn't sell their film to a studio. Avram Ludwig, a co-producer of the film, blames simple economics. "Sixty percent of revenue from films, on average, comes from overseas sales, and in Asia and Europe they just aren't interested in the black urban themes," he says. "So because these revenues are very important to make a film profitable in the U.S., there are probably a lot fewer films that are made involving [urban] themes than there are black urban moviegoers who would see them."

Often, an urban film never makes it to theater screens simply because the studio that finances it doesn't believe that the audience size will justify a release. Kitt points out that studios and distributors are perfectly aware of the money to be made in "black" movies these days; the problem is that they are interested in only a tiny range of these films.

"Very frequently they will refer to it as 'the black audience,' as if it were a monolithic thing as opposed to discrete audience segments," Kitt says. "Because of that, and the conservative nature of the industry anyway, they tend to remake movies that have been successful in the past. So the same narrow movies get made: the upscale romantic comedy, the broad comedy." No one knows what to do with movies that have inner-city themes, unknown black actors, or art-house aspirations, he adds.

Urban films very often do perform well on television and video, mainly because taking a film straight to video enables the studio to avoid the costs of printing, advertising and distribution. As Tom Ortenberg, the president of Lions Gate Films Releasing, explains, "If a film is perceived as having these ancillary possibilities built in, it can actually dissuade a distributor from taking it out theatrically. They think, if they already have a home run on TV and video, why risk it theatrically?"

That is exactly what happened with "Gang Tapes," he says. Ortenberg says that "we knew the picture had great video potential and, frankly, did not want to risk a safe profit by potentially throwing good money after bad theatrically if the picture didn't work."

Lions Gate ultimately gave the theatrical rights back to "Gang Tapes," which then tried to get it on screens with the help of the distribution company UrbanWorld, but to little avail. According to David Goodman, the film's producer, booking agents were telling the distributor that the film was "too strong in its depiction of gang life and that with the style of first-person presentation, it scared [theater owners]."

Even Magic Johnson Theaters -- a chain run by Loews and funded by the Magic Johnson Foundation with the hope of getting marginalized films into inner-city communities -- turned him down, despite the film's peaceful premiere in the Watts Magic Johnson Theater during the Pan-African Film Festival. Magic Johnson Theaters failed to return phone calls to comment on its rejection; other movie theaters did not explicitly cite violence as the reason they passed on "Gang Tapes." But as Kitt puts it, "No one is going to advertise those kinds of decisions. No one will come out and say that."

Theater owners are somewhat justified in fearing that showing "Gang Tapes" could trigger violence. A decade ago, riots ensued at the sold-out premieres of films like "New Jack City" and "Boyz N the Hood" when filmgoers showed up; "Boyz"-related violence left two dead and dozens injured in urban centers, including Los Angeles. As a result, theaters initiated a practice of opening urban-themed films on Wednesdays to avoid large opening-day crowds on weekends. Many theaters also began hiring additional security guards when a "black audience" was expected -- even for a movie as benign as "Barbershop." Violent incidents have been more sporadic since the early films depicting gang life -- and no single film has triggered widespread violence.

Obviously, violence doesn't just occur in movie houses showing urban films or films with predominantly black audiences. Kitt notes that Spike Lee's "Do the Right Thing" was considered contentious upon its release in 1989, and both the press and theater owners anticipated that violence would break out at screenings. Instead, it was another film -- "Batman" -- that hosted a fatal gun battle (thanks to a dispute over a box of popcorn). "You didn't hear about 'Batman' being pulled out of theaters, or anyone even suggesting it," Kitt says.

Still, fears about black audiences stubbornly persist among theater owners. Abdul Ammott's film "State Property," a sex- and murder-fueled tale about Philadelphia gangbangers, starring rappers Beanie Sigal and Jay-Z and geared for hardcore hip-hop fans, managed to book a few theaters, but the film's runs were short and tumultuous. Lions Gate also distributed this film, but found it nearly impossible to get it into theaters because of fears of violence.

"One major chain refused to play it in the beginning, but when they saw it was doing good business agreed to play it," recalls Ortenberg. "Another major chain agreed to play the picture initially but after one [violent] incident at one theater refused to play it more nationwide. We had a tougher time getting 'State Property' shown than any other film we've ever done."

The irony is that a film like "Gang Tapes" is intended to de-glamorize gang life. The violence in the movie, disturbing as it is, is not sexy -- one main character, after all, ends up with a colostomy bag, and two others die. "If you show the realities and horrors and atrocities of war, people won't want to go to war," Ripp argues. "People aren't going to want to run out and want to get involved in this violent battle because they know the repercussions. Everyone meets a negative end in the film."

And many of the cast members met such an end in real life, serving as tragic testament to the film's relevance. "Gang Tapes" doesn't seem to have taught these novice actors many lessons, so maybe it is a stretch to argue that the theatrical release of the film would somehow deter gangbangers from further violence. But it also seems unlikely to trigger riots in the art-house audiences it seeks, and it is not hard to imagine that kids flirting with the gangsta life might be repelled by what they see on-screen. Unfortunately, as long as the film isn't released, the nature of its impact is all conjecture -- which is why Ripp continues to lobby for his film, even as the situation looks hopeless.

"Hopefully, theaters will step up to bat, because it's an important film," Ripp says. "It wasn't made to incite violence; it was made to incite discussion."

Shares