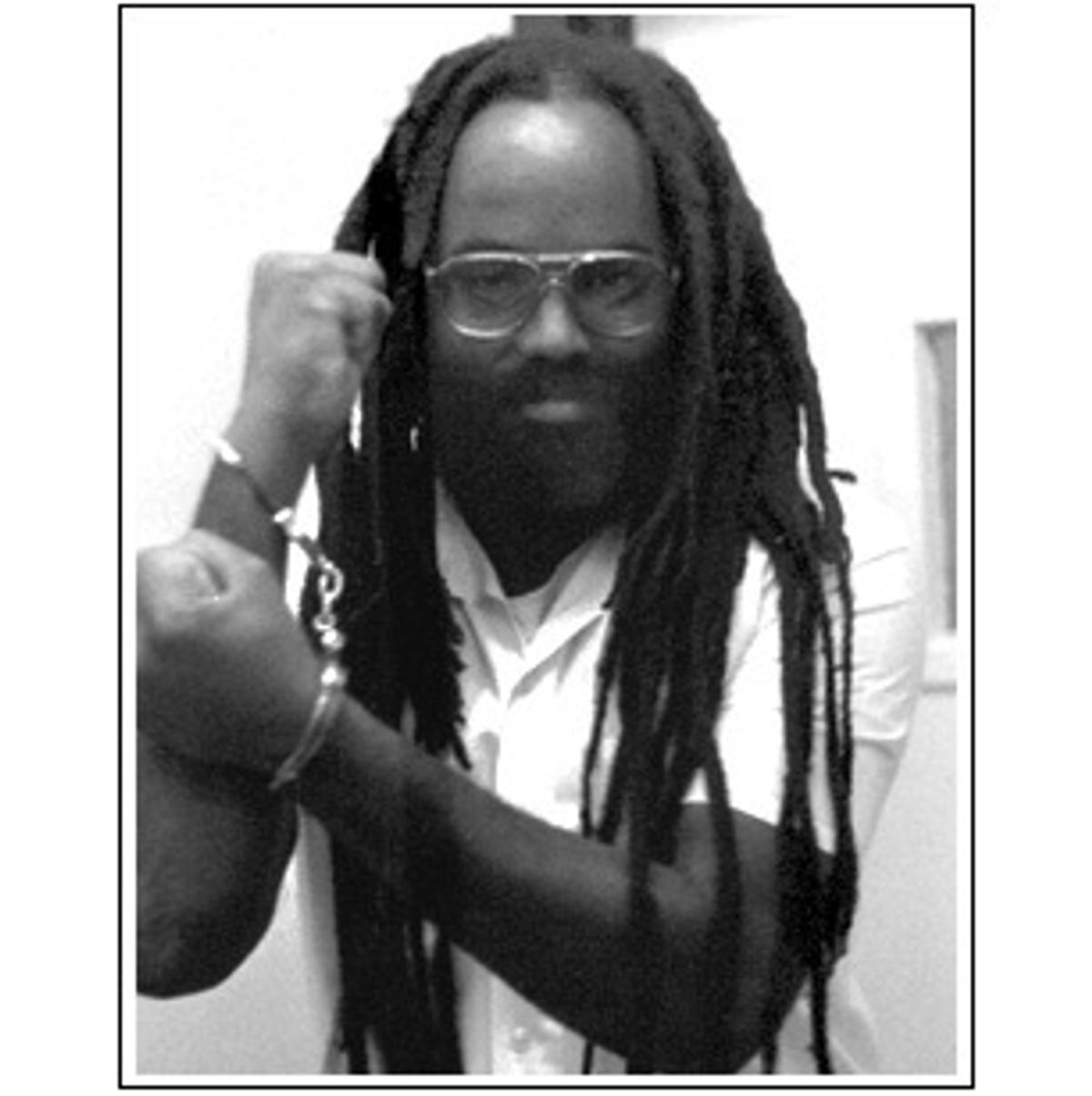

Probably the only thing the defense and the prosecution sides in the Mumia Abu-Jamal case would agree on is that the burden lies with the defense team to win him a retrial. Under the governing federal statute, the defense has to provide clear and convincing evidence that there was such endemic unfairness at the original trial that it was impossible for the defense to prove its case.

"It's the 'no harm, no foul' approach," says Daniel Williams, one of two lead attorneys defending Abu-Jamal. "The presumption of innocence only applies before a conviction. Now we have the affirmative burden of creating a very real doubt that Mumia ever had a chance. We have to show not that the trial was unfair in technical terms, but rather that it was so qualitatively unfair overall that had the unfairness not occurred, there's a reasonable probability that the outcome would have been different."

"They have to show that something was horribly wrong, so horribly unfair they couldn't prove whatever it was they were trying to prove," agrees Assistant District Attorney Hugh Burns, from his vantage on the prosecution team.

So,were there horrible wrongs in Abu-Jamal's first trial?

"No," prosecutor Burns answers, his voice angry but controlled. "The people who are supporting Jamal don't care what the facts are and don't care to know. Their claims are based on a fantasy world of what might have happened and what could have happened instead of what we know did happen."

Abu-Jamal's death sentence is now on hold; his attorneys have filed a habeas corpus petition seeking a new trial, and Burns will file his reply by early February 2000.

Meanwhile, loyalists are politicized and mobilized on both sides of the issue. It's an election year. We've lived through Rodney King, O.J. Simpson, Abner Louima, Amadou Diallo. In Abu-Jamal's case, one man -- police officer Daniel Faulkner -- is dead and another stands on the edge of his own open grave. Could the stakes possibly be higher?

Online, the confrontation is bitterly waged between those supporting Abu-Jamal and those opposed.

Amidst a massive amount of international coverage, perhaps only one author, Stuart Taylor, has been able to rise above the din surrounding this case to produce a dispassionate legal analysis; in his 1995 article for American Lawyer magazine, Taylor firmly concluded that Abu-Jamal deserves a retrial.

Taylor is hardly a squishy liberal. He is the reporter generally credited with single-handedly transforming the media view that Paula Jones' allegations were not credible into the belated realization that she in fact had a viable case. He therefore probably changed history, and helped set the nation on the path to last year's impeachment crisis. Yet, unlike his role in the Jones case, Taylor's pronouncement in 1995 that Abu-Jamal's trial had essentially been a sham met with a thundering silence from his colleagues in the mainstream press.

In his quest for a new trial, Abu-Jamal's claims cluster around the contention that he was convicted on the basis of three flawed factors: (1) concocted confessions, (2) unreliable eyewitnesses who had reason to lie and (3) a biased judge who excluded blacks from the jury and suppressed exculpatory evidence.

The Confessions

"I shot the motherfucker, and I hope the motherfucker dies."

Two months after the shooting, hospital security guard Priscilla Durham reported to police that she had heard Abu-Jamal yell out this dramatic confession twice from the emergency room floor while about 14 or so police officers tried to subdue him the night of the crime. None of the police officers had reported Abu-Jamal's incriminating statement.

Officer Gary Wakshul, who had ridden with Abu-Jamal to the hospital, at first reported that the suspect had "made no comments." Two months days later, however, Wakshul stated that Abu-Jamal had in fact confessed to him that night. The police officer explained that he hadn't realized at first that the confession was of any importance.

It took Officer Gary Bell, Faulkner's former partner and best friend, about two and a half months to remember that he, too, had heard Abu-Jamal confess. He said that had initially been too traumatized at his friend's brutal murder to appreciate the importance of what he had heard on the night of the crime.

The Witnesses

As an outspoken political radical and a Black Panther, Abu-Jamal had been monitored by police since his early teens. He had a mammoth FBI dossier, and he claims to have been beaten by police numerous times. Yet, he had never been charged previously with committing an act of violence. When I asked Assistant D.A. Burns why he thought the heretofore non-violent Abu-Jamal would callously execute Faulkner and then brag about it, the question seemed to surprise him.

"I don't know. He was well known for having a grudge against the system, being anti-police. [Officer Faulkner] had hit -- subdued -- Jamal's brother, who had been resisting arrest, striking an officer." (A charge to which the brother subsequently pled guilty.)

Of course, proof beyond a reasonable doubt of malicious, unprovoked killing with "deliberation and premeditation" are required for a first-degree murder conviction -- the charge which sent Abu-Jamal to death row. What Burns is describing is not premeditated and, as he seems to implictly admit, defending one's brother is a natural human impulse. In the eyes of the law, this is not first-degree murder.

According to the prosecution's reconstruction of the case, Abu-Jamal decided in an instant to shoot Faulkner in the back from close range, then did nothing while the wounded officer (who was facing at least two assailants and wielding either a flashlight or billy club) turned, unholstered his weapon and fired, striking Jamal in the chest. Faulkner fell to the ground whereupon Abu-Jamal fired more shots at his upper body before coolly finishing the prone officer off with a bullet between the eyes.

"Its not my theory, I don't need a theory," Burns says forcefully. "That's eyewitness testimony."

At the scene, cab-driver eyewitness Robert Chobert at first told police he'd seen the shooter run away but subsequently identified Abu-Jamal in the paddy wagon. Other witnesses say Abu-Jamal never ran; he was found 4 feet from Faulkner, gravely wounded. Later, Chobert altered his story, saying the shooter didn't get far, maybe 30 or 35 steps (about 100 feet).

Neither could Chobert consistently identify the shooter's physical characteristics or his clothing. The jury never learned of his first statement, wherein the shooter "ran away". Even more damning, the jury was not told that Chobert had a drunk-driving record for which his license was suspended both on the night of the murder and during the trial. The jury also didn't learn that Chobert was on probation for arson-for-hire and had asked the authorities for help with his various legal problems. (Abu-Jamal's defense didn't know some of these things either.)

Prostitute Veronica Jones attempted to testify, according to Jamal's former counsel, Anthony Jackson, that the police had offered to let her work unmolested if she'd finger Mumia. She claimed that was the same deal police had given Cynthia White, one of their star witnesses. The Judge barred all such testimony and struck the portion Jones had managed to blurt out from the record. Jones, the Faulkner Web site details, was a heavy drug user with a hefty rap sheet.

Prostitute Cynthia White's version of events evolved as well, each time becoming more helpful for the prosecution even as her version failed to gibe with others' significant details. White, though, would seem to have received little in return for what Jamal supporters claim was her deal with the police; because she was arrested several more times. However, Abu-Jamal claims White was arrested because she recanted or was about to. The prosecution denies that White ever recanted or would have. White is now dead.

There are more witnesses, with similarly conflicting memories and statements.

The Judge

"Nobody tried before Judge [Albert] Sabo got a fair trial," Stephen Bright of the Southern Center for Human Rights says. "He's the country's leading hanging judge."

Prosecutor Burns disagrees: "Judge Albert Sabo is a jurist of impeccable credentials who conducted a scrupulously fair trial in the midst of terrible conditions created by Jamal himself."

It's true that Abu-Jamal's behavior during the trial bordered on the psychotic. He insisted on representing himself and on having John Africa, a local activist and non-lawyer, sit at counsel table with him. He indulged in outbursts and insults and treated his court appointed attorney, Anthony Jackson, with outright contempt.

Abu-Jamal was ejected from his own trial numerous times. During jury selection, part of which Abu-Jamal conducted himself, some prospective jurors confided to Judge Sabo that the defendant "scared them to death" by his manner.

Abu-Jamal's supporters charge that Judge Sabo allowed the prosecutors to inflame the jury's fears by repeating Abu-Jamal's youthful pro-Black Panther pronouncements from 12 years before (when he was 15). It is a well-settled issue in the law, however, that a defendant's abstract beliefs cannot be used unless they are directly relevant to the crime at hand.

So, should Abu-Jamal get a new trial?

Tucker Carlson, a conservative journalist who has written about Abu-Jamal's

case, probably speaks for most people when he says, "Look, I'm horrified by the thought of innocent people in jail. But you can't just poke holes at what happened. You have to tell us why this guy is innocent."

For the majority, it all comes down to that, of course. Those who want to see Abu-Jamal denied a retrial harp on the fact that neither he, nor his brother, have ever explained what happened that morning. (Defense attorney Williams counters that Abu-Jamal will tell his story in court if and when he is granted a new trial.)

But Abu-Jamal is under no legal obligation to tell his story. And the real point here is not in fact Abu-Jamal's guilt or innocence. The point is whether or not he got a fair trial. Under our judicial system, fairness of process is the only way civilized people can have confidence that guilt and innocence have been determined, since we can't read minds.

If Abu-Jamal was not fairly tried, then he should be retried. Fairly, the way any one of us would want to be tried were the power of the state to haul us into court, and especially were the state poised to take our lives. You cannot

believe in the rule of law, or our constitutional system of democracy and disagree with that proposition.

So, was his original trial fair? No. It was certainly typical in many ways, however. Poor and minority defendants often face rushed trials defended by outgunned public defenders in our criminal justice system. They often face prosecutorial "irregularities" as well.

For their part, police and prosecutors are confronted with an overflow of perpetrators who are guilty at the least of something, if not the specific crime as charged. And jurors of all races routinely send people to prison on the basis of scanty or contradictory evidence and/or conflicting testimony. The difference in Abu-Jamal's case is that a poor black defendant has somehow become a celebrity.

In the end, Abu-Jamal is probably going to use his celebrity status to do what O.J. did -- buy himself some reasonable doubt. He's probably going to get a retrial where the prosecution will have to put up a real fight -- and he probably deserves one.

Did Abu-Jamal shoot Officer Faulkner? He probably did.

Premeditatedly? Probably not.

Before or after Faulkner shot him? This is a very important question and one the federal court should focus on. Faulkner likely was in legitimate fear for his life and fired on Abu-Jamal, who was running toward him, and who then returned the fire.

What about the unidentified man who some witnesses said fled the scene? That needs to be thoroughly investigated, as was not done in the first trial.

Stuart Taylor believes that the best hope for a retrial lies in a judgment of ineffective assistance of counsel. "That's the best way to sugar-coat a reversal. Judge Sabo is shockingly biased but courts don't like to have to say that about other judges."

If the federal court grapples directly with Judge Sabo's handling of the trial, we can have faith in their ultimate decision. If they do not, there will certainly be more Mumia Abu-Jamals to come, and poor and minority communities perhaps be forgiven if their faith in the system continues to crumble.

In the end, justice for dead policeman Daniel Faulkner, cut down in the prime of his life and leaving a young widow whose life is forever scarred, will not be served by executing a framed man.

Not even if he is guilty.

Shares