Often, after reading an incomprehensible dollar figure, I'll Google "What does a trillion dollars look like?" to get myself fired up. One example of where this takes you shows a million dollars (pathetic, wouldn't fill a grocery bag), a billion (interesting, I could fit it in a truck), and then a trillion. (Wow, it spreads for acres! Look at that tiny human included for scale!)

Yet we've committed not $1 trillion to the incompetent and/or corrupt, but more than $4 trillion. That's according to a report to Congress from Special Inspector General Neil Barofsky, the overseer of the bank bailout program.

Technically, Barofsky adds, Wall Street's IOU to you and me is at about $3 trillion these days, since some of it's been paid back. Relieved? Don't be. As these tsunamis of public wealth pour out, ignore the slosh and focus on the order of magnitude. The entire gross domestic product -- the number reflecting all wealth generated in this nation for this year -- is only $14.1 trillion. So whether the sum of our money that's now their money is $3 trillion (1/5 of all wealth generated in America in a year) or $4.7 trillion (1/3 of all wealth generated in America in a year), it still means that, for a big chunk of the year, every single one of us was working for Goldman Sachs et al.

Barofsky's report also suggests that Wall Street's tab might ultimately work out to $24 trillion, which would be $80,000 per American, or $320,000 for a family of four. But that's, like, totally the worst-case scenario. (Still, wouldn't it be impressive? I envision huge, 5-foot-cubed, shrink-wrapped pallets of dollars dropping from the sky onto my neighborhood, smashing houses, crushing cars, killing beloved pets, blasting craters into asphalt streets. Yeah!)

Smallpox and bikinis

And yet could we employ this financial muscle in a more constructive way?

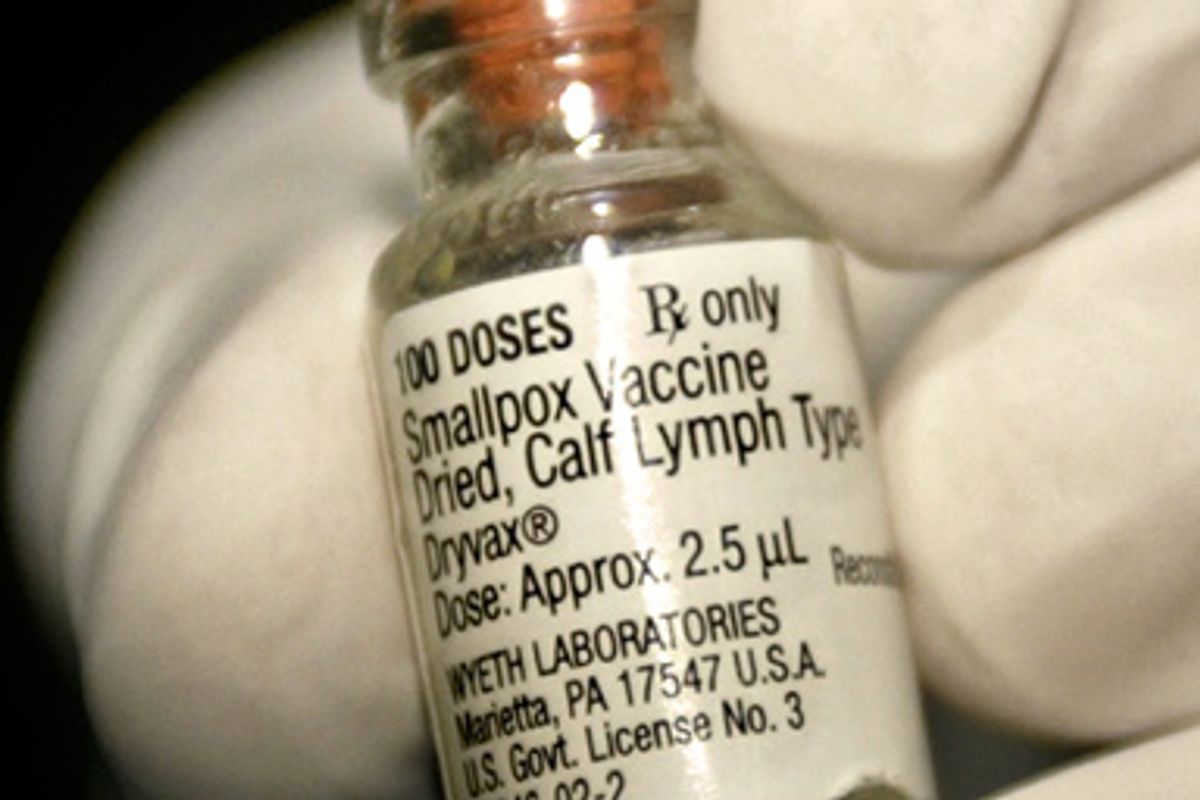

For an illuminating example, consider how we dealt with smallpox. That airborne virus, with its fevers reaching 106 F and signature pus-filled skin eruptions, was the greatest killer of man ever known.

In the 20th century, smallpox killed more people than all of that bloody century's wars combined.

In fact, if you tally the worldwide death tolls for World Wars I and II, the Korean and Vietnam wars, the Iran-Iraq war and the Mexican Revolution, the civil wars in China and Russia and Spain, and all the other wars of the last century, from Afghanistan to Zaire, the total is less than one-third of the smallpox death toll.

And that's just a single 100-year period, for a disease that disfigured Egyptian pharaohs, allied with Hernando Cortes to rout the Aztecs, left a young George Washington scarred, later stalked his Continental Army, and left Abraham Lincoln pale, weak and dizzy as he delivered his Gettysburg Address.

And yet, in the 1960s, smallpox was targeted by visionary public health experts -- and in just 10 years it was gone. An excellent new book by D.A. Henderson, the doctor who led the effort, tells the story: "Smallpox: The Death of a Disease."

This was a signature achievement, up there with defeating the Nazis or walking on the moon. To track down a virus in every corner of the planet, encircle it with vaccinations and kill it ... I began to wonder how many 5-foot-cubed pallets of Benjamins the world had brought to bear. After all, this was mankind's greatest killer -- the Joker to our Batman, Lex Luthor to our Superman. The amounts of cash flung about must have been awe-inspiring.

Chasing down the cost of the 10-year eradication campaign was not easy. Eventually, Dr. Henderson himself steered me to a 1,450-page official history of smallpox maintained as a PDF in a sleepy corner of the Web site of the World Health Organization (WHO). The answer, hidden away on page 1,366: $300 million.

Three hundred million?

Not trillion? Not even billion?

Such a tiny sum of money for such a tremendous feat? It's like hitting a home run at Fenway Park using a chopstick for a bat.

The price paid to defeat humanity's greatest foe wouldn't cover a 24-hour day of Iraqi combat operations. In Wall Street bailout terms, there's no way to even talk about sums this tiny. To do that, we have to go the level of overcompensated individuals. So, sure, $300 million could eradicate history's greatest killer of humans -- yet the same sum wouldn't cover the bonus pool for the executives of the insurance company AIG after its great meltdown. It's less than what just one man, Lehman Brothers CEO Richard Fuld, pulled down over the past five years.

It's even more striking if you remember that this was a price tag for a worldwide program whose cost was shared by multiple governments; and also a total cost over a 10-year period. To think about it in annual budgeting terms, it works out to $30 million a year. Which is approaching the ridiculous. Hell, the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit issue for 2006 featured a blonde in a bikini of diamonds worth $30 million.

We fight over there so we don't have to fight here

These are sad economic times, sadder still when you consider the tsunamis of wealth going to waste: $4 trillion for Wall Street welfare queens; somewhere from $1 trillion to $3 trillion for anyone affluent enough to own a top hat and a monocle; another trillion or so (and counting) for our current military escapades abroad.

But it's also just damned exciting. Because, frankly, it's a helluva lot of money we have to play with! Even now, at one of our darkest economic hours, we could be performing miracles with the spare change left behind the national couch cushions.

If you're an engineering type, you might prefer that those miracles involve shoring up our creaking national infrastructure. Good! Go write your own article.

I'm a doctor so I'll stick with medical possibilities. Since the smallpox triumph, public health experts have been inspired to target other diseases for eradication. One is polio, a virus known for paralyzing a minority of its unluckiest victims, among them former president Franklin D. Roosevelt; two others are Guinea worm and leprosy, plagues dating back to the Bible.

The World Health Organization and the volunteer service organization Rotary International have spent two decades tracking down and vaccinating billions of people against polio. They calculate that they've prevented the paralysis of 5 million children worldwide.

Just this May, a 10-day frenzy saw the immunization of more than 222 million children in Africa and Asia. It was possible to watch the campaigners' march through Africa on Google Maps. Among the foot soldiers in that vaccine war: Ali Mao Moallim, who more than three decades ago became the last person on Earth to contract wild smallpox. (Others have caught smallpox in the laboratory since.)

Think about that: inoculating 222 million children in 10 days. For comparison, there are only about 80 million children in the entire United States.

Imagine inoculating every child in America in 10 days. In 10 days, we couldn't even get every voter in Florida to figure out whom they chose for president.

Not so long ago, polio roamed the globe, and each day would paralyze 1,000 children. Today, there are only some hundreds of cases each year, mostly in underdeveloped areas of Africa and Asia.

The entire 21-year slog has so far cost $5 billion. By comparison, Wall Street executive bonuses last year -- not salaries, but bonuses, for a single year that saw the whole mess collapse and the taxpayers handed the broom -- came to $18 billion.

If you look at the polio campaign costs on an annual basis, it's about $240 million a year, or less per year than it has cost to occupy Iraq per day.

The United States has been polio-free since 1994. But if the polio campaign falters, the virus could return. This, unlike Iraqi military operations, truly is a case of having to fight them overseas so as not to face them at home.

And why would the polio campaign falter? Because there are huge demands on the public purse and we must spend judiciously; otherwise, Wall Street CEOs would have to pay for their own $87,000 area rugs and $68,000 credenzas. (What's a credenza? I had to look it up. Turns out it's that sideboard thing you only see in the movies, where Wall Street villains keep their decanters of fine whiskey for toasting the paralysis of small children.)

Casting out the fiery serpent

Consider another lifesaving success-for-pennies program that's evolving right now, in fact racing against polio to be the next public health triumph. We are on verge of eradicating Guinea worm, a parasite believed to be the "fiery serpent" that torments the Hebrews during the Exodus. Go read your Bible, it's in there.

A female Guinea worm matures in its victim's gut, growing 2 feet long. Then, over a year marked by cramping, nausea and fevers, it burrows out of the intestines, down through a leg, and to the skin surface. A blister forms accompanied by a burning sensation -- hence the "fiery serpent." The agonized victim immerses the leg in water for relief; on cue, the worm releases a cloud of larvae. Others drink downstream, and the cycle repeats itself.

Treatment involves digging into a blister to seize the worm's head, then extracting it over days to weeks by wrapping it around a stick -- a therapeutic image that some argue may have inspired the Rod of Asclepius, the physician's symbol of a snake coiled around a staff.

Guinea worm still plagued millions when former President Jimmy Carter organized a charitable foundation and challenged his advisors to suggest a disease to stamp out. They nominated Guinea worm: Humans are its only host, so if the cycle is broken in people, the parasite will be gone.

Thanks to larvicides, nylon water filters, and education, we are almost there. Today, there are fewer than 5,000 recorded Guinea worm cases in six African countries. The total cost of this 23-year campaign to date has been $225 million. Or less than $10 million a year.

This sort of chump change is so small, you can't even talk outsize salaries; you have to focus on the tax breaks on those outsize salaries. So, consider that the following celebrities have saved the following estimated sums each year on their taxes, courtesy of Bush-era tax cuts: movie producer Jerry Bruckheimer, $5.8 million; L.A. Laker Kobe Bryant, $1.6 million; rapper 50 Cent, $6 million; real estate mogul Donald Trump, $1.2 million.

Imagine a sort of congressional reverse earmark -- one that canceled the Bush tax cuts only for Bruckheimer, out of punishment for "Armageddon" and "Pearl Harbor" -- and steered the resulting millions to disease control efforts. Really, would any of these men notice the slightest changes in their lives if they returned to paying Clinton-era tax rates?

When curing millions of leprosy is "failure"

But wait. Aren't some of these public health campaigns wasteful failures? Sure they are. Let's look at one public health failure: the drive to eliminate leprosy.

Caught early enough, leprosy can be cured today with the antibiotics dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimine. Over 25 years -- courtesy of Novartis pharmaceuticals and the Japanese Nippon Foundation -- these medicines have been handed out for free, and have cured more than 14 million people of the disease. They work so well that the World Health Organization now recommends integrating the world's 250,000 known leprosy patients into primary-care settings, just like those with any other illness.

Treatment is so effective, in fact, that several years ago the WHO launched a campaign to eliminate leprosy entirely. Ultimately it sank 15 years and about $200 million into the project. (I cannot find a link for the $200 million figure, provided to me by WHO officials in e-mail correspondence.)

But there's a logistical nightmare when trying to eliminate leprosy. Other targets such as smallpox, polio and Guinea worm exist in one reservoir only: sick humans.

Not so with Mycobacterium leprae, a bacterium that attacks skin and nerve cells. Even today, we don't know everywhere this bug lives. It has been found in the oddest places: in armadillos in Louisiana and Texas, in the noses of healthy people in some parts of the world, and even in some soil samples.

Such a bug was never an easy target. Even so, in 1991, the WHO vowed its "elimination" -- and then defined "elimination" to mean less than one case per 10,000 people. At such a low background level, it was hoped, the disease might dwindle into irrelevance. It hasn't worked. That 1-in-10,000 target was arrived at via politics and hopeful thinking. It was achieved worldwide in 2000, putting the WHO in the risible position of claiming "elimination!" and then seeking more money to, like, eliminate it some more.

The organization was bitterly criticized. Earnest, indignant treatises have been written noting that there is too little money to go around, and accusing the WHO of risking the credit of the more promising drives against polio and Guinea worm.

So, the anti-leprosy push was a $200 million failure.

Because it didn't eradicate leprosy.

It only cured 14 million people.

Of leprosy.

For half the price of an Alaskan bridge to nowhere.

Oddly enough, $200 million is reportedly the tax deferral enjoyed by former Goldman Sachs CEO Henry Paulson -- he of bailout infamy -- when he joined the Bush Cabinet as treasury secretary.

So there you have it, finally: For $200 million of public money we can take a walk in the footsteps of Jesus Christ himself, curing millions of leprosy. A truly inspiring future is, as always, easily within reach, if we choose it.

Or we can just give Hank Paulson a tax break. Maybe throw in a credenza by way of thanks.

Shares