When Illinois Gov. George Ryan commuted the sentences of all the state's 167 death row inmates to life in prison earlier this month, the media was flooded with the searing cries of victims' families. "My son is in the ground for 17 years and justice is not done. This is like a mockery," Vern Fueling told the AP.

This sentiment of Feuling and others like him has become the flash point for critics of Ryan and for death penalty supporters. Discussions of possible retrials, or even of the grisly details of the murders committed by some of the men and women now suddenly off death row, took a backseat to another concern: How will the victims families feel?

In USA Today, Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the victims-rights group Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, wrote that "Gov. George Ryan's commutation of the sentences of Illinois' entire death row is a travesty of justice." DuPage (Illinois) County Prosecutor Joe Birkett complained that Ryan "hasn't heard the cries of these families. And there's nothing I can do or anyone can say to undo the pain that he has inflicted on these families." Richard Devine, Cook County state's attorney, called the decision "stunningly disrespectful to the hundreds of families who lost their loved ones to these Death Row murderers."

Those arguments are grounded in a fairly simple premise: Support for the death penalty has as much to do with meting out eye-for-an-eye vengeance on behalf of victims' families as it does with following the law of the land. This support hinges on the idea that the death penalty is necessary for these victims' families -- victims, themselves, by extension -- to "move on" and finish the whole hideous trauma of a murder so they can resume their lives. When John Ashcroft pushed to have Timothy McVeigh's execution televised, he spoke of bringing "closure" to the victims. Mercy for the innocent mandates death for the guilty.

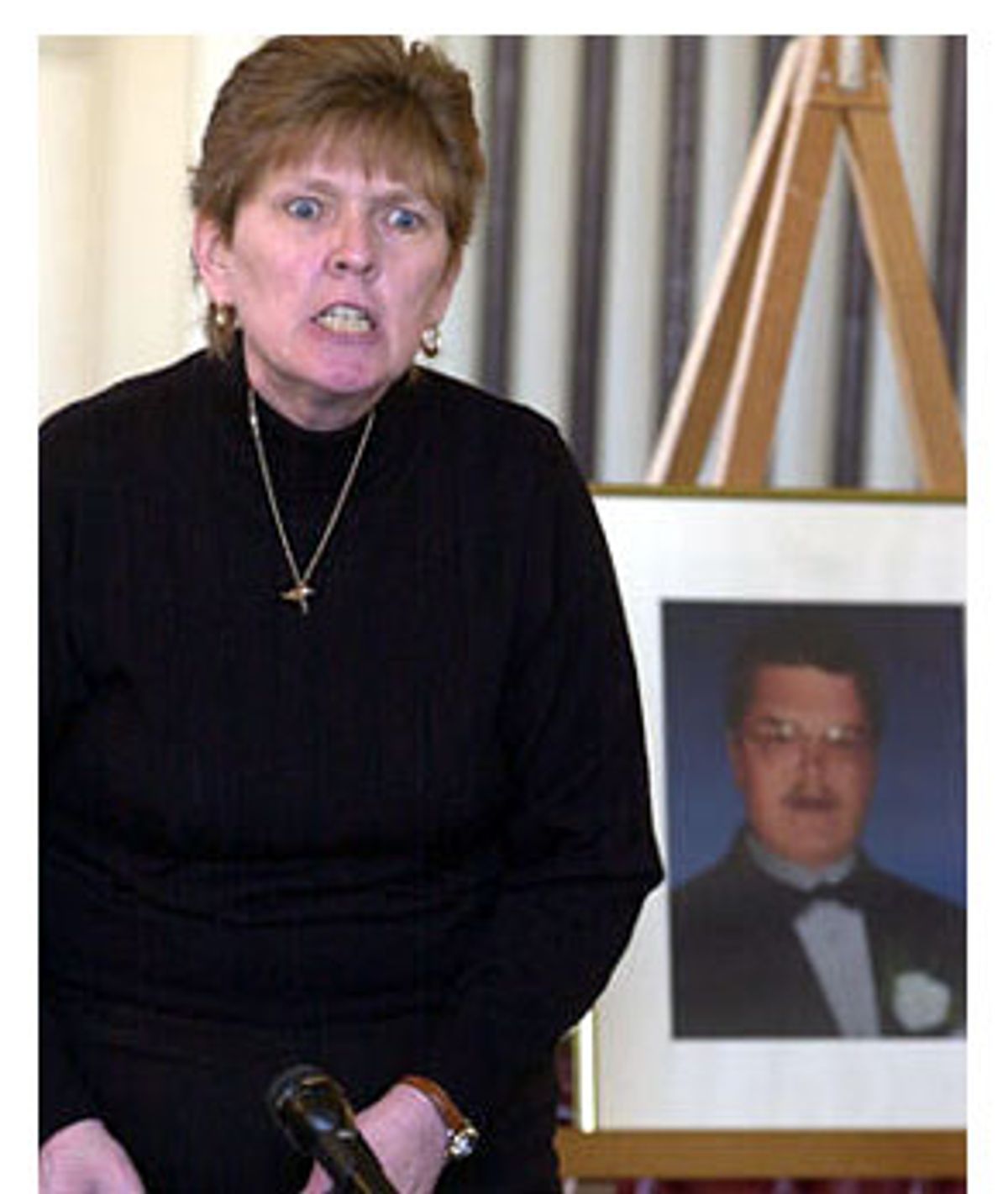

It's a belief the families cling to. "We were looking forward to the death penalty. My younger sister was looking forward to seeing it," says Mary Heidcamp, a 62-year-old Chicago woman whose mother's killer, Oasby Gilliam, had been on death row eight years before Ryan commuted his sentence. "I'm just so disappointed in the whole system, I can hardly sleep at night thinking about it."

Gilliam is the kind of killer whose savagery trumps most well-reasoned arguments against the death penalty. He carjacked 79-year-old Aileen D'Elia, locked her in the trunk, and later beat her to death. If Gilliam's death would comfort Heidcamp, most Americans would support it.

In fact, though, there's little reason to believe it would, at least in the long run. No psychological study has ever concluded that the death penalty brings "closure" to anyone except the person who dies, and there's circumstantial evidence that it can prolong the suffering of grieving families. That's why Bud Welch, an Oklahoma gas station owner who lost his 23-year-old daughter Julie in the Oklahoma City bombing, says, "George Ryan in Illinois did a tremendous service to the victims' family members, though they don't realize it. Now those people will understand that it's over with and they have to move forward."

For victims' families who oppose the death penalty, as well as for some who support it but derived little comfort from the execution of their loved ones' killers, it's a myth that the death penalty heals. They say the pop-psych media formula, that catharsis equals closure, has been mostly created by a society desperate to believe that even the worst wrongs can be righted.

"It's amazing to me to think that anyone could truly believe that sitting and watching another human being be murdered could heal them, but I did," says Oregon anti-death-penalty activist Aba Gayle. For eight years after Douglas Mickey murdered her 19-year-old daughter Catherine in 1980, "I was in such a state of anger and rage, I was lusting for revenge." It's a lust, she says, that was encouraged by the prosecuting attorney. "The district attorneys are very careful to let you know they're there for you. They tell you, 'We're going to convict him, and when he is executed, everything's going to be OK. It's a magic bullet they're offering to all of these victims' families."

Yet families who've actually been through the tortuously long emotional and legal process from one death to another say there are no magic bullets -- and anyone expecting one is just setting himself up for more pain. Of course, some families celebrate the deaths of their loved ones' killers. But few find relief in it, and often the waiting and the appeals and the eerie anticlimax of an execution can only serve to rekindle the pain.

John Byrd, the man who murdered Sharon Tewksbury's husband during a convenience store robbery 19 years ago in Ohio, was put to death last year on Feb. 19. Tewksbury wanted him killed and she's glad he's dead. Over the years he was in prison he'd threatened her family from death row, writing her letters about his friends on the outside who would "take care of us," she says. "If the man who murdered my husband had at any time shown extreme remorse and asked to talk to me, I might have done it, but in 19 years all he did was threaten to hurt us. There are people in this world who are just plain evil. It has nothing to do with faith and religion and believing or not believing."

Yet Byrd's end has done little for her and her family. Certainly, she feels safer: "The death penalty for my children and I gave us the freedom to know that this man was never going to hurt us again or anyone else again," she says. Still, there was no release, and now Tewksbury speaks of the execution with surprising ambivalence. "None of us felt elation. None of us felt overjoyed. I don't have strong feelings about the death penalty one way or the other now. My goal is to get all of the media to understand that 'closure' is a bad word, a word survivors don't understand. 'Transition' is the word we use. That doesn't mean everything is OK. Never will it be OK, and no execution, no jail sentence, nothing, will help in that process."

Such a reaction isn't uncommon. Austin Sarat, a political science professor at Amherst College and the author of the 2001 book "When the State Kills: Capital Punishment and the American Condition," says that although there haven't been large-scale studies of the effects of the death penalty on victims' families, anecdotal evidence suggests it often fails to ease anyone's pain. "If you study victims' groups, you find that reaction to the process is very divided," he says. "Many people who witness an execution as relatives of someone who's been murdered come away disappointed, especially where lethal injection is the method, because there's literally nothing to see. For other victims, seeing someone die at least provides the assurance that this person will never do it again."

Today, Tewksbury works as national volunteer coordinator for Parents of Murdered Children. She agrees that victims are frequently disappointed after a long-awaited execution. "Sometimes it doesn't come to them right away, because they're all caught up in the moment," she says. "But further down the road you wake up thinking, 'I'm still missing the person that I loved, nothing's changed, and I don't feel any better.' It's a long hard struggle to work through grief. Some survivors have the ability and the energy and hope to do that, and others don't and their lives are just destroyed."

Welch has seen the same thing. "I'm on the board of directors at the Oklahoma City National Memorial, and I know a lot of victims' family members. For five years prior to [McVeigh's] death, I was saying, 'You're really looking for closure, you're looking for something to help you feel better when you kill Tim McVeigh, and I'm afraid you're not going to find it."

More than most other death-penalty opponents, Welch viscerally understood how the families felt. Right after Julie was killed, he was desperate to see McVeigh die. In 1999, he told a Harvard audience, "After McVeigh and Nichols had been charged -- I mean, fry the bastards. We didn't need a trial, a trial was simply a delay. You no doubt probably saw at some point McVeigh or Nichols being rushed from an automobile to a building, bulletproof vests on, and the reason that the police do this is because people like me will kill them ... Because had I thought that there was any opportunity to kill them, I would have done so."

As the months dragged on, though, Welch had to contend with the memory of his daughter, who was passionately opposed to the death penalty. At 16, she had founded a chapter of Amnesty International at her high school. He remembers that while driving her home from college during her junior year, she'd been enraged by a radio news report of an execution in Texas. "Dad, all they're doing is teaching hate to their children in Texas," she told him. For months, the conflict between her politics and his pain tormented him, and he eventually came out against McVeigh's execution and traveled to western New York to visit McVeigh's father, Bill.

McVeigh was executed on June 11, 2001. Since then, Welch says, "Not a single person has told me they benefited from it. I've had about five people tell me that it really didn't help them any," he says. Some came to that realization while McVeigh was still alive. Welch says that at one survivors' meeting several years after the bombing, a widower who'd wanted the death penalty suddenly said, "You know what? Hell, it ain't going to help me when they kill that guy."

Of course, that doesn't stop some victims families from hoping it will. Stardust Johnson plans to watch the death of the man who killed her husband eight years ago, even if it takes another decade. She'd been married to Roy Johnson, a music professor at the University of Arizona, for 35 years when he was kidnapped, robbed, beaten to death and left in the desert by Beau John Greene, who was high on crystal meth. "We had an unusually happy marriage," she says, her voice cracking. "We were very close, very loving and caring. I was so fortunate, I can't tell you how fortunate I was to have met Roy and had those 35 years, but I'm growing old alone and I sure didn't count on that."

"Before my husband was murdered I probably was not in favor of the death penalty, but after [Greene] brutally took the life of my husband, who was a beautiful human being, I do feel that the death penalty is appropriate for him," she says. "I think that what it does is give a sense of release. I don't want him to be out there anymore. I would like that chapter closed."

Johnson doesn't expect the execution to happen for at least another decade, which means she'll have waited 18 years for the sense of release she longs for. Meanwhile, the appeals process has been grueling. Recently, she says she told a friend it might have been easier if the killer had gotten life in prison so "there wouldn't be an appellate process and it all would have stopped. It's the appellate process that continues and drags you in that's really difficult to deal with."

It's a common complaint among survivors. "Either have it or don't have it, but don't carry it out for 19, 20 years," says Tewksbury.

"If anything prevents closure, it's the death penalty," says Richard Moran, the author of last year's "Executioner's Current: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and the Invention of the Electric Chair" and a criminologist at Mount Holyoke. "If you have a trial in which the person is sentenced to life imprisonment, it's over, that's it. If the person is sentenced to death, you will be contacted by authorities and will relive that murder every two years for the next 15 years. Then, if they finally do execute the person, then you can start beginning your closure. What it does is, it puts off any healing. Wounds are being reopened and whole process is being prolonged."

Johnson surely echoes other victims' families when she says she thinks death row convicts should be allowed only one appeal. But such a solution would only exacerbate the problems that led Ryan to empty his state's death row in the first place. "Thank God for the long appeals process, because there are a hell of a lot of people we would have killed that were wrongly convicted if we didn't have it," Welch says. In Illinois alone, 17 death row inmates have been exonerated, many after more than a decade in prison. As it stands, when it comes to the death penalty, there's no way to reconcile the victims' desire for a speedy conclusion with the need to make sure the state doesn't put innocent people to death.

So these cases can drag on for years. In 1999, Welch testified at a hearing for Manuel Babbitt, who'd been on death row at San Quentin nearly two decades (he was put to death later that year). Babbitt, a decorated Vietnam vet and former mental patient, broke into the home of 78-year-old Leah Schendel, beat her and tried to rape her. She died during the assault. At the hearing, one side of the room was dominated by the Schendel family, the other by the Babbitts. "I didn't even say what I had intended to say, which is that what we have seen unfold before us this day is an absolute American tragedy," Welch says. "The state of California chose 20 years ago to put Manny Babbitt on death row, and two large families have been unable to move on with their lives for 20 years."

He believes the Schendel family was the more ill-served by the process. "If you take Manny from his cage and kill him, the Babbitt family will be able to move forward," he remembers thinking. "The Schendel family will not find peace and they will not be able to move forward for some time."

His assessment is backed up grief experts, Moran says. "Most of the psychiatric literature would say those who forgive have a better chance of letting go of it. Some people can find it in themselves to forgive, and they do the best. I don't know if I would be capable, but if I were to advise myself on what I needed to do to survive if something like that happened to me, that's the strategy I would try to follow. It's the only one that works."

And, of course, it's a strategy that the death penalty precludes. Welch says it was "very important" to his own healing process that he was able to make his peace with McVeigh. Had he watched McVeigh's execution hoping to find comfort in it, he believes he might never have transcended his own fury. "God didn't make normal human beings to feel good out of watching another human being take his last breath," he says.

Shares