If the Winter Olympics are ever held in Kabul, the bucolic district of Paghman, just to the city's west, will be an important site for events. Tucked into the mountains just above the city, with its scenic vistas and orchards, Paghman is the perfect base site for downhill skiing, bobsledding or luge. With the snowcapped peaks above it and the picturesque city below, it couldn't be a better backdrop for televised winter sports.

Yet the Olympics aren't coming anytime soon; Kabul isn't ready quite yet. Much of the city is still in ruins, destroyed during the civil fighting here 10 years ago, and the civilian population today is still plagued by attacks from rogue troops and police, the mujahedin veterans who, with the backing and support of the United States, swept back into the city when the Taliban collapsed. Extortion, corruption and poverty are everywhere.

Paghman is a particularly bad area. I interviewed several families there last month and earlier this year, and like the people in U.S.-occupied Iraq, they described lives of constant physical threat and deprivation. Many families reported regular robberies by army and police troops there -- soldiers under the command of Paghman's local leader -- as well as rapes, kidnapping and ransom schemes by local military commanders.

Even the city of Kabul, often touted as the one secure area in the country, also has problems, and the thieving gunmen that plague its streets, most people say, all come from Paghman. (Paghman is a district within Kabul province, which itself extends well beyond the city limits.)

I asked one victim in west Kabul city, who was robbed by a gang of troops, how he knew the men were from Paghman. He laughed. "I followed their footprints," he said, explaining that on the night he was robbed, it had rained in Kabul, and the troops had left clear prints in the mud. The next day, he said, he found some Kabul policemen and they pursued the lead.

"We followed the footprints up toward Paghman. We got to a little fort, used by the army there," he said. But then, the Kabul policemen got scared and turned back, telling the man that they could not challenge such strong military people.

Many of the footprints from crimes committed in the Kabul area lead directly to Paghman's de facto ruler, Abdul Rabb al-Rasul Sayyaf -- an archconservative Islamic fundamentalist with links to extremist Saudi groups, whose main sub-commanders are running extortion and kidnapping cartels right out of central Paghman. While Washington exults in the overthrow of the medieval Taliban regime, warlords like Sayyaf continue to enforce strict Islamic social codes including restrictions on women's education and dress.

Sayyaf, a major mujahedin leader from the past who allied himself with the U.S. in fighting the Taliban, is one of the most powerful men in the new Afghanistan. Sayyaf's influence extends beyond Paghman. He was an important force in creating a post-Taliban government, and he is a leading force in the country's current efforts to adopt a new constitution. Afghanistan's future, long-term or short-term, cannot be planned or predicted at this point without taking him into consideration.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Most people outside of Afghanistan have the mistaken perception that the country leads a divided existence, with urban stability on the one side and rural chaos on the other. There is the city of Kabul -- the conventional wisdom goes -- an oasis of security in which there are embassies, an international military force, a relatively stable government, even a new Thai restaurant. Outside the city limits, though, there are the lawless rural areas in which former mujahedin warlords run wild and remnants of the Taliban maraud in the mountains. In recent days, the Taliban has escalated its attacks on the shaky, U.S.-backed government of President Hamid Karzai, killing nine police officers in eastern Afghanistan on Monday after taking four others hostage, launching a murderous attack on a district governor's house, and ambushing Afghans who work for a British charity. In all, some 80 people have been killed in the last week, making it one of the deadliest since the U.S.-led overthrow of the Taliban regime in December 2001.

If Kabul could control the rest of the country, the hope goes, things would get better. Yet this isn't an entirely accurate picture. In reality, the lawlessness of renegade warlords and strongmen like Sayyaf, whose troops operate in west Kabul, extends right into the city itself. The capital city's perceived political stability is in many ways an illusion. Many of the most destabilizing figures in Afghan politics are not in the hinterlands, but right in Kabul. Numerous government officials in Kabul -- many of them former commanders who received support from the United States during the 1980s and again in their fight against the Taliban -- are now engaged in underhanded dealings, corruption, and human rights abuses against civilians. Several leaders, including members of the Cabinet, have been involved in attacks and death threats directed at potential rivals and critical journalists, as well as in abusing their governmental posts to increase political support. Kabul is filled with rogues and troublemakers. Sayyaf is just one of the most menacing.

Sayyaf is, basically, the political kingpin of Islamic fundamentalism in Afghanistan. He is the man who put the "Islamic" into "The Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan," the country's current name (he spearheaded the effort to change the name at last year's "loya jirga," or grand council, charged with picking Afghanistan's current government). An adherent of the Wahhabi doctrine of Islam, the ultra-conservative branch of Islam practiced widely in Saudi Arabia, Sayyaf was responsible for bringing many Arab fighters to Afghanistan during the 1980s to train and fight against the Soviet Union's occupying army. He also opposed the United States' involvement in the first Gulf War, and maintained ties through the 1990s with several anti-Western Islamic groups, including one of the more powerful fundamentalist groups in Pakistan, Jamiat-e Islami.

Sayyaf has tried to put his fundamentalism into practice through his commanders and troops. Once, last year, after arriving late to a meeting with some international legal experts, he apologized by stating that he had been instructing "his commanders" in Sharia, or Islamic law. And obviously the troops have taken his teachings to heart. Sayyaf's men in Paghman have broken up weddings at which music is being played, and beaten up villagers for listening to music on cassette players. Paghman villagers told me a few months ago of how the governor of Paghman, a protégé of Sayyaf's, beat up some old men at a wedding in late 2002, insulting each of them in turn for listening to music:

"He made them stand in a line, and he walked down the line, looking at each in the face. He would look at them, like he was deciding, and then he would start slapping them in the face. And as he slapped them, he would say things like, 'Be ashamed of your acts! Look at your beard! At your age, how old you are! You should be ashamed!' It had been the first time there was music in Paghman in a long time. There was no music when the Taliban was in power."

Sayyaf's power extends to the highest levels of the Afghan government. He appointed most of Afghanistan's current judiciary -- mostly clerics in rural areas -- as well as many of the country's provincial governors, especially near Kabul. The governor of Kabul province, Taj Mohammad, is one of Sayyaf's men, and many police and intelligence officials in Kabul are primarily loyal to him. President Karzai himself is often forced to bow to Sayyaf's demands.

This summer, Sayyaf offered a raw display of his power to two newspaper editors, Sayeed Mir Hussein Mahdavi and Ali Reza Payam Sistany, who dared to challenge his dominance in Kabul. Mahdavi and Sistany, until recently, ran a new Kabul periodical called Aftab, or the Sun, which offered a refreshingly critical perspective on the country's political order. In early June, they wrote a series of articles harshly attacking Afghan clerical leaders, including Sayyaf and the former president of Afghanistan, Burhanuddin Rabbani (also a powerful man), both of whom are considered to be Islamic scholars.

In one of the articles, astringently titled "Holy Fascism," Mahdavi raised questions about these leaders' use of Islam to dominate Afghanistan's political processes. The article was largely sarcastic, especially with regard to Sayyaf. It contained several rhetorical questions about Sayyaf and Rabbani's wealth, inquiring how, for instance, after paying their Zakat, the religious tithe that Muslims are required to pay, "they can afford to purchase so many Four Wheel Drives [SUVs], houses, and employ a great number of servants," and asking why, if they were such pious Muslims, they had been involved in current and past criminal activities including, "shooting of artillery, bombing, on innocent undefended civilians." Both Rabbani and Sayyaf have "bloody hands," the article said, because of their involvement in civil fighting in the early 1990s. The article referred to the time when the Soviet-backed regime in Afghanistan collapsed in 1992 and infighting broke out among rival mujahedin parties vying for control, during which the armies of both men were involved in shelling of civilian areas in Kabul.

Sayyaf was reportedly apoplectic when he heard about the article. The response was swift. Clerics loyal to Sayyaf, including Afghanistan's chief justice, Fazl Ahmad Shinwari, managed to convince President Karzai to allow the men to be arrested, on the grounds that Mahdavi's articles were blasphemous. To prove this, they pointed to the remainder of the article, in which Mahdavi suggested that the general history of Islam in Afghanistan had been almost entirely accompanied by violence and repression, and asked tough questions about why ordinary Muslims were bound by clerics' interpretations of Islamic law -- a sort of Luther-like challenge to Islamic fundamentalism.

On June 17, Mahdavi and Sistany were arrested and charged with blasphemy, typically a capital crime under Islamic law. Karzai ordered the two men released a week later, after he came under pressure from international officials and groups like Human Rights Watch, but the two then went into hiding and their newspaper was closed. Having received death threats before their arrest, the two editors understandably feared for their safety. Mahdavi tried to get protection from the United Nations, while Sistany, who is an Iranian national, sought help from the U.N. refugee agency, UNHCR.

Despite their desperate situation, both Mahdavi and Sistany still had a sense of ironic humor when I saw them in July, joking about how much more danger Karzai himself was in, for letting them go. Meeting me at a Kabul hotel, they expressed fears about their security, but managed to joke about their predicament and the United Nations' inability to help them:

"The U.N. pressured the police to help us," Sistany told me, laughing. "But the police only sent a few men, who were four inches shorter than me and 20 kilos lighter." Sistany himself is a small, thin man. "Since I figured these thin men wouldn't really help me, I sent them back to be with their families."

Later, Sistany got a new apartment in Kabul, with help from the U.N., but he was still too scared to go outside. "I can't even go shopping for food," he said.

Sayyaf hasn't commented on this case publicly, which is typical of him. Part of Sayyaf's strength stems from the fact that he often keeps a low profile. (As do I. As a human rights researcher, I often have to lie low in Kabul, which is why I never ask to meet Sayyaf during my trips there.) He doesn't impose himself personally in most political affairs, and when he does meet with foreigners, he knows exactly how to charm them.

An Afghan news producer described Sayyaf's wiliness to me earlier this year: "Sayyaf has two faces, one for the Western people, and one for the fundamentalists. When the Western people go to see him, he speaks their language: progress, reconstruction, human rights and democracy. When the fundamentalists go to see him, he speaks their language: Sharia, the glory of the mujahedin, Islam. Everybody hears what they want to hear."

The same producer also suggested that part of Sayyaf's power derived from the large sums of money he receives from foreign sources, including Saudi religious groups -- a charge reiterated by other critics.

"He has uncountable money," he said, lowering his voice to a whisper. "He easily has handed out money to NGOs [non-governmental organizations] that are doing little projects. He gave $200,000 to a close friend of mine, for some little project. He is the most very clever leader. We have no one as politically strong as Sayyaf."

Yet that's not entirely true. There are other leaders in Afghanistan whose power rivals Sayyaf's, and thus surpasses Karzai's, both inside Kabul and in rural areas.

Afghanistan's defense minister, Mohammad Qasim Fahim, is one of the country's leading strongmen. Fahim, the primary ally of the U.S. in fighting the Taliban, currently commands a private militia of tens of thousands, barracked northeast of Kabul, independent of the official army. He also controls most of Afghanistan's official military -- largely composed of other militias left over from the Northern Alliance -- as well as the 5,000 troops in the newly trained Afghan army. Fahim's political base, the political organization Shura-e Nazar, is derived from the support base of the late mujahedin leader Ahmed Shah Massoud, the powerful anti-Taliban commander who was assassinated in northeast Afghanistan on Sept. 9, 2001. Fahim's Shura-e Nazar was the primary recipient of the massive amount of cash and weapons that was funneled to the anti-Taliban resistance by the CIA in the weeks and months after the Sept. 11 attacks. (Today, Fahim continues to receive assistance from the Russian government, although this has been repeatedly denied by both Fahim and the Russian Ministry of Defense.) Officially, of course, President Karzai is the leader of the national government, but in reality, Fahim and Shura-e Nazar control most Kabul-based government offices.

One reason Fahim is so strong is that he is allied with Sayyaf, whose political networks among the country's Pashtun population are vital to Fahim, who is ethnically Tajik. Inversely, one of the reasons Sayyaf is so strong is that he is allied with Fahim (and Shura-e Nazar). Sayyaf, despite having no governmental post, can call on the assistance of many of Kabul's main commanders under Fahim.

Afghanistan is full of mutually reinforcing relationships like this one, on smaller local levels. These types of alliances are what the politics of Afghanistan are made of. As many Afghans point out, Karzai isn't really the leader of Afghanistan; he's simply a figurehead over a set of rival parties vying for control. In reality, the Afghan state is just a complicated anarchy in which various local players, with varying amounts of power, exert power over one another in different ways.

There are no functional political processes in the country, just naked power dynamics. And this is to be expected: Afghanistan's provincial governors, village mayors and police chiefs are really only local military strongmen -- usually former mujahedin -- who are ostensibly allied with Karzai but ultimately loyal to no one. Many are self-sufficient, independent sovereigns over the areas under their control, and act and think as soldiers. The political dynamic resembles a battlefield, a state of war, even with Afghanistan at peace.

Most Afghans refer to their country's local leaders as jangsalar, Dari for "warlords," or tufangdar, "gunmen," which is, essentially what they are. Kabul journalists use the term "warlordism" to describe the country's core problem (which allows them not to name names). And yet warlordism also has a cause, which journalists are glad to point out if you ask them.

"The Americans," said one newspaper editor to me, in July. "The Americans put the warlords into power."

"Something is rotten in the Islamic State of Afghanistan," an old Afghan is saying to me one night after dinnertime. He is a Kabuli, a local humanitarian worker, and he seems to like making literary jokes. We have just dined together on fried chicken and rice in his small apartment. He is explaining why he is pessimistic about Afghanistan's future.

"The leaders are criminals," he says, referring to Afghanistan's warlords. It is a cool spring night earlier this year, and the old man is sitting on his couch across from me, lecturing me about the past. All of Afghanistan's current military and police leaders, he says, have blood on their hands from past war crimes. Specifically, he refers to the civil fighting in Kabul from 1992 to 1995, detailing how various commanders, including Fahim and Sayyaf, were involved. They killed, he says, and now they rule.

"Like Hamlet's uncle," he says. "But," he continues, "they have no remorse."

As usual at night in Kabul, it is very dark in the apartment. There is no electricity, and the old man's face is lit up by the ghastly white glare of a propane lamp. In fact, he looks like he could play the ghost of Hamlet's father. He is an intellectual; he was once a professor. The dramatic lecture works well for him.

The Soviets were terrible, he admits. The regime they imposed in Afghanistan in the 1980s was relentless and cruel, and the country was a police state. But when the mujahedin took over Kabul, he says, life became "the law of the jungle." People were made into beasts.

As the evening goes on, he brings out photographs of his youth, when he was studying abroad, before the war. He shows me pictures of him, seated with some other Afghans in Italy. He also shows me pictures from an art book filled with Picasso sculptures of nude women, one of which he calls "my mistress." It is late and he is a little drunk: At some point in the evening, a bottle of grain alcohol has appeared, to be mixed with the warm Coca-Cola on the table -- a rare event in dry Afghanistan. He sighs.

"The guys in charge now, they destroyed everything," the old man says, referring to the civil war in Afghanistan in the early 1990s. "All the beauty in this country, and in this city, Kabul. They destroyed the natural and the art-i-fice," he draws out the word, "I mean the flowers and the trees, and the architecture. It was beautiful here, then, very, very beautiful ..."

His eyes are wet. The gaslight hisses. In the distance, there is typical Kabul night noise: It sounds like thousands of dogs are barking at each other. The old man is looking down at the Picasso sculptures, shaking his head.

Sadly, I have seen this sort of thing before: grown men reduced to tears, even when sober, describing Afghanistan before the communist revolution in 1978. When the Taliban was in power in 2001, and there was a severe drought in Afghanistan, I saw tearful Kabulis pointing to the withered grass and ruined buildings, lamenting the country's fate. In Kandahar, in early 2002, I saw pomegranate farmers cry while talking about how their farms and gardens looked, before the Soviets came.

The dirges are a standard theme for many older Afghans when they discuss current Afghanistan. Before the war, older Afghans say, every garden in Kabul had a bevy of fruit trees: apricots, peaches, apples and pears. In the summer, the tree-lined streets were shady and the evening breeze was cool and fresh. In the winter, the distant mountains were tipped with snow, and you could sit by a stove with freshly sugared walnuts and tea, watching the children play in the snow.

A lot of foreigners who travel to Kabul don't seem to appreciate Afghanistan's pacific past -- the fact that the country was at peace for most of the 20th century. Many journalists, when writing about their time in Afghanistan, describe the destroyed military planes and tanks lying around Kabul's airport, the warlords, and the ruined houses that stretch for miles in south and west Kabul, as though Afghanistan has been a war zone since the beginning of time. There is not much discussion of how Afghanistan turned out as it did, of what life was like before the destruction, and -- the most sensitive subject -- who destroyed the country in the first place.

Of course, the question of who destroyed Afghanistan is a sensitive one, because some of the people who are implicated -- like Sayyaf and Fahim -- are currently in power.

It's also a complex question, because the country was destroyed by many people, with many different motives, over a lengthy period of time. Blame tends to need a focus, but in Afghanistan, truly, blame can be thrown in all directions. One person can argue that the Soviets are the prime culprits: After all, they invaded the country in the first place. But another can point out that Kabul city was destroyed not by the Soviets, but by mujahedin parties fighting with one another after the Soviets withdrew in 1989. A third might join here: "That all happened because the Americans gave them weapons, which in turn was the result of the Soviet invasion." And why did the Soviets invade anyway? Isn't it true that the country was ripe for a rebellion, since Afghanistan's feudal and paternalistic society (which the mujahedin fought to protect) was so socially unjust? Why not bring the British Empire into the equation, the Russian Tsars, Alexander the Great, and so on?

The debate can go on forever, and it probably will. But the one historic fact that seems most relevant now is that Afghanistan today is ruled, to a great extent, by some of the same mujahedin leaders who were responsible for reducing it to rubble. Many Afghans have not forgotten what happened in the early 1990s in Kabul, so they look at current leaders, like Fahim and Sayyaf, and they worry.

American officials, for their part, do not realize how important these ghosts from the past are, as they have allowed these same leaders to dominate Afghanistan's political landscape.

I have spoken to many U.S. officials and military officers about these issues, in both Kabul and Washington, and have briefed staff in the State Department, Pentagon and National Security Council, describing this common Afghan perception about Kabul's current leaders. I have even testified before Congress about this issue. There are signs that opinions are starting to shift in official Washington, but for the most part the Bush administration still clings to its line on Afghanistan. When confronted with complaints about warlord-dominated Afghanistan, administration officials resort to a stock "things are better than they once were" lecture: "Look, you have to appreciate the fact that the Taliban is gone. The Taliban was terrible. The Taliban beat women on the streets, and cut off people hands for petty crimes. Under the Taliban, girls couldn't go to school and men had to grow ling beards. Today, girls are back in school and civil society is flourishing, newspapers and businesses are opening, and there is peace. Of course, there are still security problems, and remnants of the Taliban are creating problems, especially in the south and east. But for the most part, our understanding is that things are improving, and Afghanistan is on the road to recovery."

Most officials now know better, but you'll never hear them express their doubts in public. On Women's Equality Day last year, President Bush issued a glowing report on Afghanistan and his administration has adhered to this theme ever since: "In Afghanistan, the Taliban used violence and fear to deny Afghan women access to education, health care, mobility, and the right to vote. Our coalition has liberated Afghanistan and restored fundamental human rights and freedoms to Afghan women, and all the people of Afghanistan. Young girls in Afghanistan are able to attend schools for the first time."

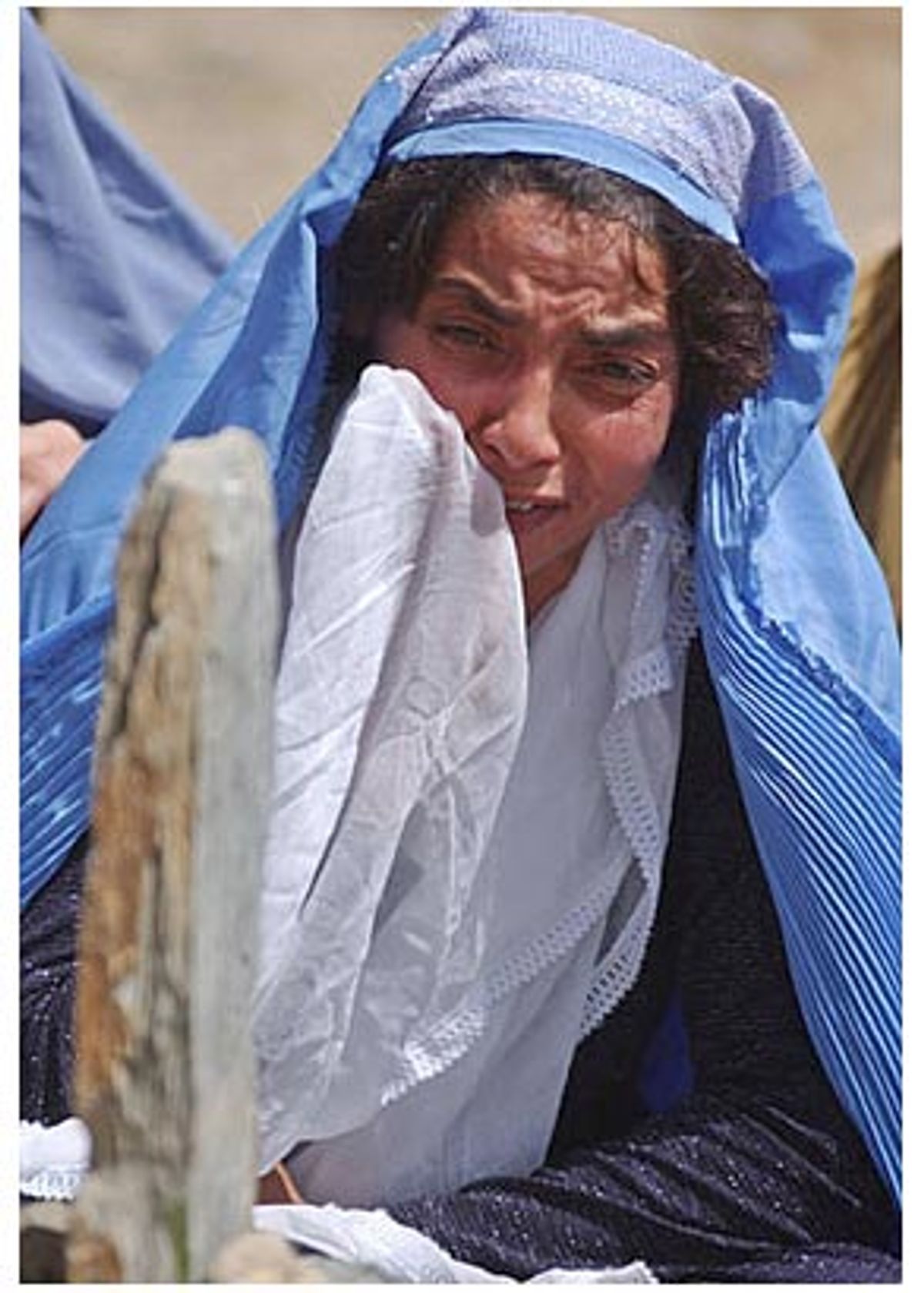

Many Afghans, especially women, have found this sort of unfounded cheerfulness, and the comparisons to the Taliban era, annoying. (The fact is that the majority of school age girls in Afghanistan are not back in school.) One Afghan woman, an activist, put it succinctly to me in a meeting in July: "When you compare life to the Taliban, just about every situation seems like a paradise. Afghan women want their rights to be judged in the same ways women's rights are judged in other countries. Not by the Taliban standard, but by the human rights standard."

Across the country, Afghan activists and political opponents are tired of being told that their country is on the mend when they know it is not, and they are frustrated with the dominance of Sayyaf, Fahim and their kind. But they are even angrier about the explicit threats they receive whenever they actually challenge the warlord dominance in public.

One political organizer I ran into in July, who runs a small periodical in Kabul, told me a story that seemed to sum up the country's warlord problem. Earlier this year, the organizer fell afoul of Sayyaf after he published an editorial in his paper that alleged the warlord might have been involved in the killing of civilians during fighting in west Kabul in 1992 and 1993. The organizer told me that the day after he published the article, he received several threatening calls from Sayyaf himself, while he was traveling to Paghman to attend a wedding there.

"When Sayyaf understood I was in Paghman, he tried to find me. He called me on my mobile phone while I was eating lunch. He asked me to come and see him.

"I said, 'Sir, at the moment I am eating, and I cannot see you,' But he insisted that I come to him." But the organizer, fearing that he would be arrested, stayed where he was.

"Half an hour later he called again and he said to me that I should to come to see him. I again refused. He got angry and said, 'You have written nonsense, trash; you have degraded me and insulted me. What you have written is an indignity for me. You have insulted and degraded the mujahedin, and you are traitors to the achievements of the jihad.'

"I said, 'Sir, what have I done wrong? I just reflected what you say you had done in the jihad. You should not have done those deeds which you repent now.'

"'Juan Mak,' he said. It means 'Damn you, God kill you.' Then he said, 'You do not know what you have done. I am a jihadi leader. It is an insult to me.'

"I said, 'Sir, please, this issue cannot be solved on the telephone. We can see each other and talk about this later.'

"He said, 'I want you to come immediately.'"

The organizer started to fear that Sayyaf might find him in Paghman.

"Well, I left immediately with my family for Kabul. When I got back, I received another call from him. He wanted me again to come to him, but I said, 'Sir, forgive me, I am in Kabul.'"

Later, the same organizer was visited and threatened by members of the army and Afghan intelligence service, the Amniat-e Melli.

He has kept a low profile since, and hasn't gone back to Paghman.

Shares