One story has Tenzin Gyatso, the current Dalai Lama, asking for pockets to be sewn into his robe. He was a child at the time, and his tutors were shocked. They tried to explain that his traditional garments weren't to be modified, that the previous 13 Dalai Lamas had made do without pockets. They might as well have been speaking French -- the boy wanted a way to carry things, and there was no arguing with him.

Whether the story is true is not important. On this side of the Himalayas, it's the mythic version of the Dalai Lama that matters. On his great ascent to the Western pantheon of celebrity, the spiritual and political leader of Tibet has had to scrap a few personal quirks to transform himself into a more compact, digestible idea. It's a transformation familiar to anyone who has risen from the ranks of nuanced nobody to iconic somebody in America -- a formality. Some might balk at the distortions wrought by fame, yet they don't have a country to save. And who knows, renouncing one's former self is probably good exercise for a practicing Buddhist.

Most of us have settled on a few facts about the Dalai Lama: The most prominent and powerful lama of the four main schools of Tibetan Buddhism, he attends to matters of state, culture and spirituality. (He's the head of the Gelug school, and lamas of the other three schools look to him as both a secular and a religious leader.) He does so from his government in exile, having lived in Dharamsala, India -- "Little Lhasa" -- since China invaded Tibet more than 40 years ago. He does so advocating world peace and compassion, despite his experience with oppression, a commitment that earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. He does so while living as "a simple Buddhist monk -- no more, no less."

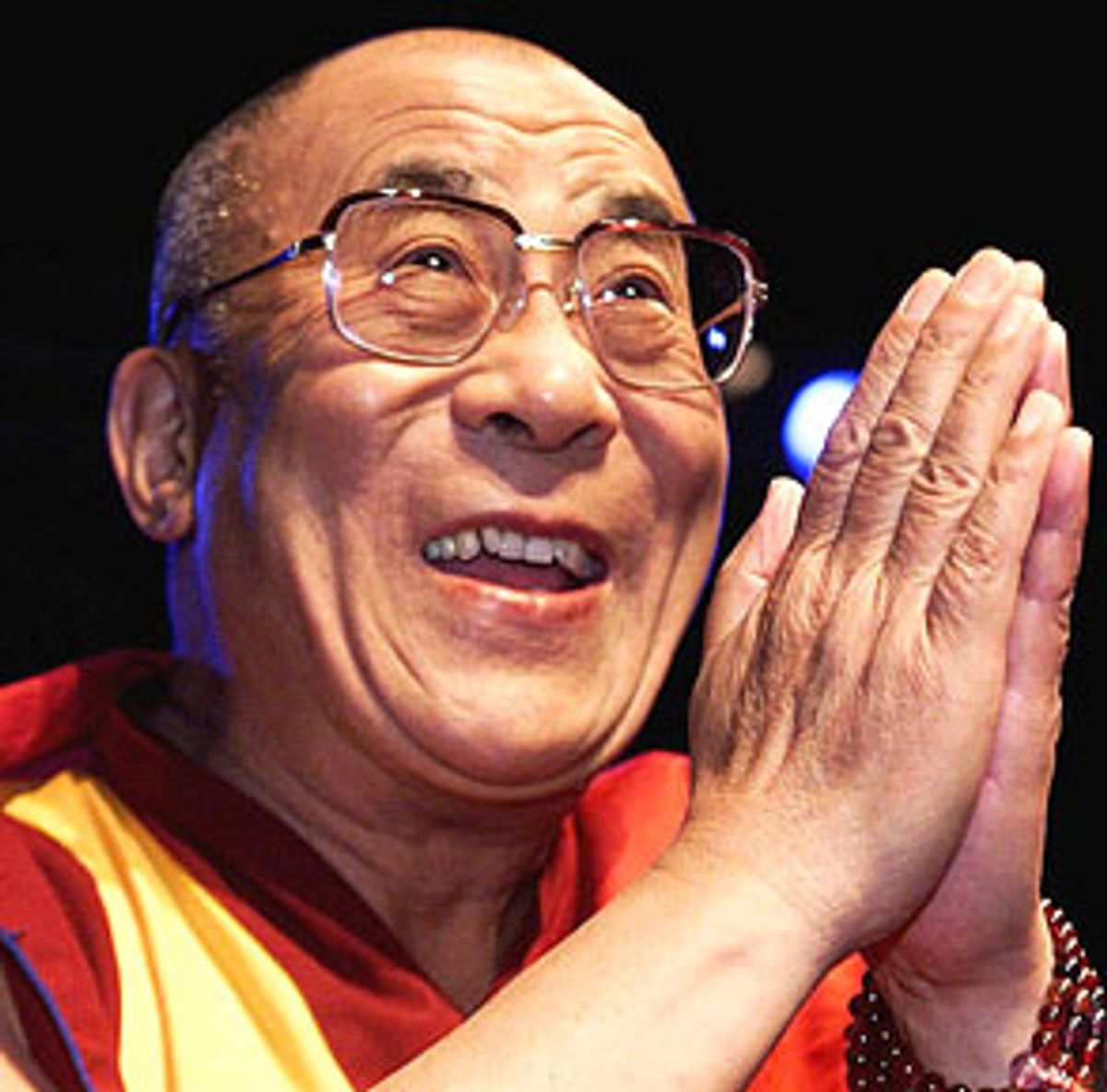

We know this much, and we can picture his maroon robes, his trademark eyeglasses. Still, some mystery persists, even under the bright searchlights of fame: Why is the Dalai Lama laughing? What's so funny? Is it us?

Back up to 1937. A 2-year-old named Lhamo Dhondrub in the small, northeastern Tibetan village of Taktser sits across a table from four intent out-of-towners. Choose a "mala" (rosary), the men say, offering two. The boy chooses correctly. Choose a pair of eyeglasses, they say; choose a staff. Every item he chooses belonged to the previous Dalai Lama. The boy's earlobes are big and his eyes long -- more good signs. Finally the visitors peel back his clothes and find eight marks, each in the right place. The men look at one another. Their two-year-long search has ended: The child is the next incarnation of the bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara. He is unquestionably the 14th Dalai Lama.

The boy was brought to Lhasa, Tibet's capital, placed in the care of tutors, and over the years he was prepared for the day he would come of age and assume control of Tibet. There was no doubt that the right child had been selected -- the Dalai Lama was bright, compassionate, good-humored and wise. And then in 1950, the choice suddenly mattered more than ever. Eighty thousand soldiers of the People's Liberation Army crossed the eastern border of Tibet, and China demanded that Tibet "return to the motherland." At 15, three years ahead of schedule, the Dalai Lama assumed full control of his country.

Before Mao Tse-tung, Tibet had maintained varying degrees of autonomy, despite China's regular efforts to control and influence its strategic neighbor. For years, the Dalai Lama tried to establish good relations with Communist China. He proposed various types of allegiance between the two nations, but Mao rejected any plan that didn't acknowledge China's total, unalloyed sovereignty over Tibet.

Tensions came to a head in '59, and the Dalai Lama, along with close to 100,000 other Tibetans, fled to India. The conflict, of course, extended beyond borders into ideology. "Mao wanted to change the world through struggle and revolution," Sinologist and dean of UC-Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism Orville Schell has noted. "Tibetan Buddhists accepted the world as they found it."

More than 30 years later, the one known to Tibetans as Yeshe Norbu, or "the wish-fulfilling jewel," is engaged in a daily struggle to reverse, or at least stall, China's annihilation of his homeland. And he is also poking strangers' bellies before collapsing in giggles. Why is the Dalai Lama laughing?

Maybe he thinks we're funny. Maybe we are. We love Buddhism but misrepresent it, spinning our wheels on the slippery patches -- is it a religion or a philosophy? Is there a difference? Our skepticism gets in the way. The story of the Dalai Lama's selection as No. 14, for example, derails the average secular American: Seemingly arbitrary signs -- cloud formations, crows on a roof, patterns on a lake -- led to his discovery, and yet his discovery clearly was not arbitrary. We question what we know, and we get no closer to enlightenment. When the Dalai Lama politely advises American Buddhists to remain in the United States rather than move to Tibet or India, he's speaking to the Western Buddhist's tendency to misunderstand; if you're chasing understanding all over the world, he suggests, you're not getting it.

Even if the Dalai Lama is laughing at us, we don't mind -- we can't help loving him. Although "we" may not encompass all Americans, it's a diverse group that includes liberals, moderates, conservatives, young people, old people, mainstream media and the cultural elite. And while members of the left aren't always willing to take up a cause so far from home, despite what their bumper stickers might proclaim, the Dalai Lama has been able to reach them. And here lies one of the most fascinating aspects of his brilliance: At a historical moment when support for his cause is more crucial than ever, he has the ability and discretion to use his famous charm precisely as he needs to. And he is adored for it.

Why? The pool of potentially adorable people is larger than ever -- there were more than 150 nominees for the Nobel Peace Prize this year alone -- certainly large enough to obscure the impact of a single monk. Perhaps we love him because he has let himself embody the symbols that the West wants to see: We associate him with struggle, iconoclasm, underdogism and mellowness. Sure, life is suffering, but suffering's fashionable, and it makes for great rock concerts.

If the Dalai Lama works it -- if he manipulates us, or himself, for the purpose of earning support -- who can blame him? For 40 years, he has kept one eye on China's trampling of Tibet and the other on the West's consistent refusal to intervene on any substantive level. (The CIA did train a few Tibetan guerrillas from 1959 to 1971 in the Colorado Rockies, but in 1972 President Nixon shook hands with Mao, and the secret program ended abruptly.)

So the Buddhist monk does what he can, channeling his magnetism and warmth into canny P.R. savvy. Anybody can be pious, wise and good-natured, after all; but to have the free world say it's so takes a kind of marketing brilliance. The Dalai Lama is Gandhi meets P.T. Barnum, minus the elephants. He keeps his wisdom close to the ground, a move the average secular humanist can appreciate. ("The more we care for the happiness of others," he says, "the greater our own sense of well-being becomes.") The Beastie Boys love him, Richard Gere loves him, Steven Seagal loves him, and all of these people have gone to great lengths to show it. The more support the Dalai Lama receives, the more contagious his cause becomes.

He has conquered a certain vocal and visible segment in the West more thoroughly than China could ever hope to. He is loved by the people here who know him, and loved even more by those who don't. He enjoys the fame of a world leader and the adoration of a cult hero. (Even his late mother, Diki Tsering, has a place here -- her posthumous autobiography, "Dalai Lama, My Son," is doing well by Amazon's standards.) What's more, the Dalai Lama makes it look effortless. He doesn't kiss babies or mug for cameras at steel mills. Instead, the reverence tracks him down, always managing to find a surprised and amused look on his face. For the Western liberal with a penchant for the exotic, the Dalai Lama has it all.

Maybe this is what he's laughing at. All he has to do is show up and we go into paroxysms of praise. And then the praise becomes gift giving, and by the end of the day he has received a dozen new white scarves (what visitors traditionally bring him) and a fat check with a Beverly Hills, Calif., ZIP code in the corner.

It's not all charm. When it comes to earning respect, the Dalai Lama is also in the fortunate position of being in an astoundingly unfortunate position. China's invasion of Tibet ultimately left little in the way of ambivalence: The slaughter of tens of thousands of unarmed civilians, the occupation of a sovereign nation and the destruction of perhaps 6,000 temples (the significance of this last crime may be unappreciated by some; in Tibet's nomadic tradition, temples were fundamental to society) just about make the Dalai Lama's case for him. Indeed, he knows well where much of his popularity comes from: "All the credit," he says, "goes to the Chinese."

Perhaps the clarity of the atrocity resonates in the West, where few international disputes seem so cut and dried. The Kosovar Albanians never quite convinced America that they were completely innocent victims, and we're still torn between Israel and Palestine. Tibet, by contrast, is a no-brainer. Here, in a nation nostalgic for the seemingly black-and-white struggles of the comparatively simpler past, the Free Tibet cause has wings.

Wings, at least, among a certain few. The official U.S. position is that Tibet has no real claims to independence. That stance is informed, of course, by concerns over trade with China -- intervening on Tibet's behalf would jeopardize our already fragile relations. It's one of those U.S. policies that are so outrageously unjust that few are motivated to even complain, and another gulf between popular opinion and official rhetoric opens wide.

Then again, liberal-minded types were predisposed toward the Free Tibet movement to begin with. Winning the P.R. war with China is like beating a caveman at chess. Despite China's size, influence and apparent sophistication, its government still concocts propaganda the old-fashioned way: ridiculously. When it comes to garnering the moral support of Americans -- Americans who root for the little guy, who still like movies about hulking, calculating Russians surrendering to the hearty USA -- a nation that doesn't disguise its imperialist roots doesn't have a shot.

Statements leaked from a meeting of government officials in Beijing in the early '90s (and translated by the International Campaign for Tibet) reveal just how anxious and crude China's anti-Tibet propaganda can be:

"We should launch our propaganda in whatever country [the Dalai Lama] goes to ... In the whole period of the 1990s, it will not be possible to eradicate splittist forces, yet it may be possible to divide them and tear them apart ... TV programs for external broadcasting should include programs about Tibet. We should broadcast to Europe and America so that our propaganda can directly reach audiences of the Western countries. With regard to the targets of our propaganda, [we] should do a good job with high-level people, including parliamentarians of relevant countries."

China may appear bumbling, but Tibet vanishes a little more each day. The great improvements China claims to have bequeathed to the Tibetans are, as one would expect, the very instruments that are erasing them. The modernization of society in Tibet has happened via movie theaters, shopping centers and other conveniences that have gradually whitewashed traditional Tibetan culture. It's a way for China to get the thorn out of its side -- change the nature of the thorn.

The government justifies its cultural revision the way it has from the beginning: China is liberating Tibet from itself. An unjust feudalism has been removed, and secular reason is slowly replacing Buddhist mumbo jumbo. The so-called improvements also divert attention from the more direct persecution that continues to occur. Carrying a photo of the Dalai Lama can still land you in jail, and landing in jail can still mean death. Even the environment has suffered tremendously at the hands of the Chinese occupation; logging, hydroelectric projects, waste disposal, unsustainable mining and nuclear proliferation have done severe damage to the Tibetan plateau, according to a recent study by the government in exile.

China's invasion and occupation of Tibet are inextricably linked to any understanding of the Dalai Lama's identity. His homeland's predicament has shoved him into the world spotlight -- and away from the more traditional activities of a monk. As the head of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, he inherited that school's responsibility for political control of the state. (Other schools, such as the Kagyu and Nyingma, go about Buddhism quite differently and, lacking the structure and polish of the Gelugpas, wouldn't do as well as international diplomats.) The tension with China has demanded that the Dalai Lama focus more on policy than any of his predecessors did. "I do not consider myself anti-China," he has said. "I am helping the two goals the Chinese government is seeking -- stability and unity." Outside Tibet and India, he is often seen more as a political figure than a religious one.

The monk does occasionally emerge, in the West, from behind the diplomat, and the teachings we receive exceed the wisdom of the average politician: "I try to treat whoever I meet as an old friend," the Dalai Lama has said. "This gives me a genuine feeling of happiness. It is the practice of compassion."

Had Tibet remained autonomous, the Dalai Lama's governmental duties would have required far less energy, and he would have been free to devote more time to his primary obligations -- teaching and practicing Buddhism. As it is, he wakes up between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m. and manages to squeeze six hours of meditation into a day of governing.

In Tibet's 11th hour, the Dalai Lama has to put practice on the back burner now and then. He does all he can to bring money and support to organizations such as the Tibetan Youth Congress, which is struggling to preserve Tibet's heritage. At the same time, he continues to propose meetings with China. But China refuses to meet with him until the government in exile abandons all claims to Tibetan independence.

The situation doesn't look good for Tibet. The Dalai Lama talks about retiring. He has suggested that his successor, the next incarnation of the bodhisattva of compassion, may be found outside Tibet for the first time in history; with 120,000 Tibetans living in exile, that's not inconceivable. Others say there may not be another one at all; a Dalai Lama incarnates himself only when he chooses to.

Other possibilities loom on the horizon: The charismatic 15-year-old head of the Kagyu school, the 17th Karmapa, who made the news early this year when he escaped to India from Tibet, could assume political control if the Dalai Lama names him Tibet's next leader. As the only major Tibetan Buddhist lama whose lineage is acknowledged by China, the Karmapa remains an embarrassment to the Chinese government for as long he stays in India.

Meanwhile, the Dalai Lama is ever his effervescent self. The man who taught himself English, who collects wristwatches as a hobby, who arranges meetings with physicists whenever possible to hear their explanations of the universe, who shrugs happily at the radical notion of a female Dalai Lama and who waves off those who would call him a "god-king" can still be found giggling, almost daily. China continues to despise him. (With a chuckle, he says that he'd be snatched up immediately if he returned to Tibet, and that the Chinese government would issue a statement saying, "He's resting.") And the West reveres him more and more. As complex as his life looks from the outside, we believe him when he tells us he's just a simple monk. In fact, we're prepared to believe just about everything he says.

Shares