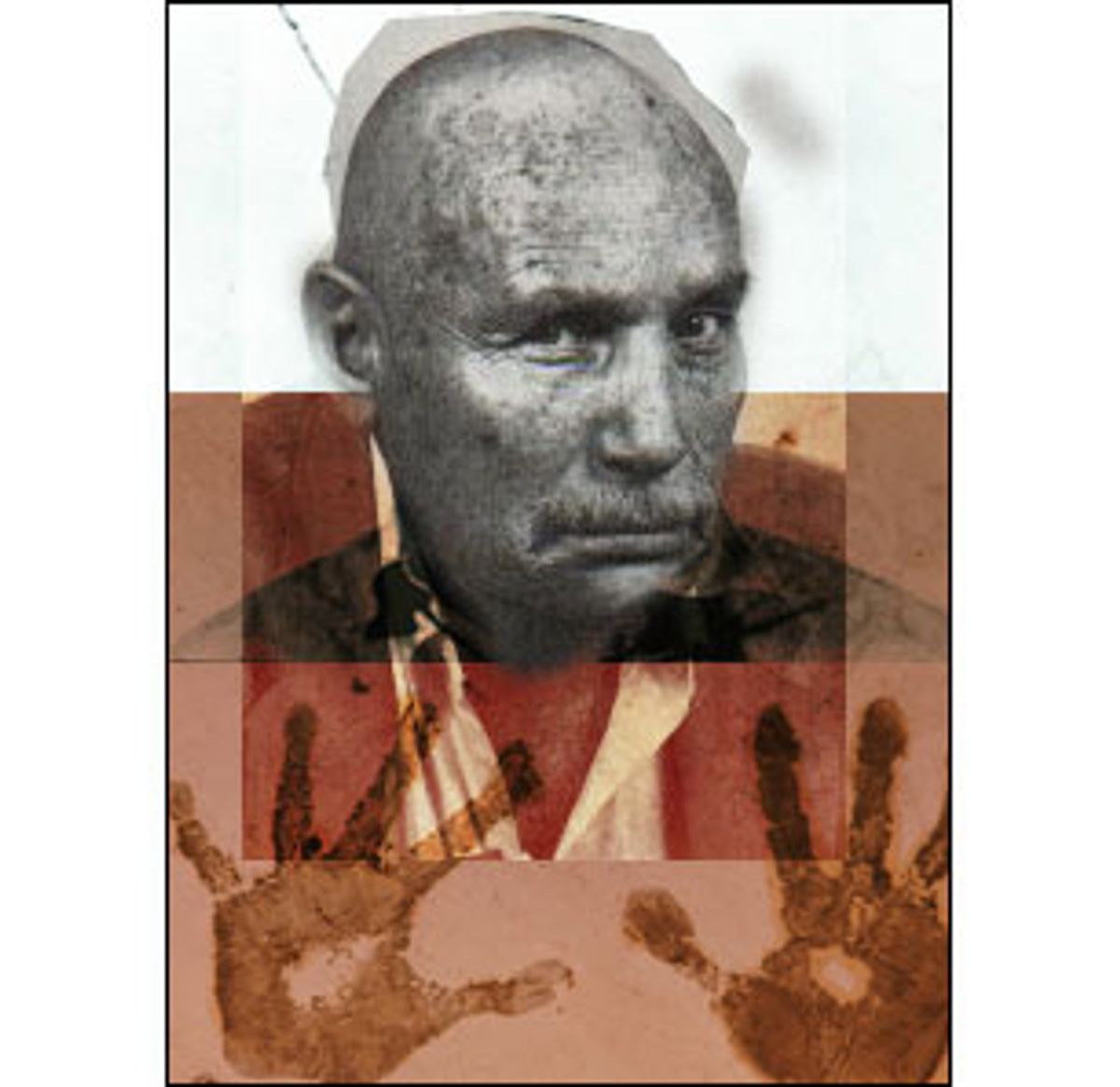

Edward Bunker has a face like an ax, a voice like a buzz saw and the watery blue eyes of a saint. Standing in the middle of an office garage behind his picture-perfect home in L.A.'s tony Hancock Park, he lights a half-smoked cigar for the umpteenth time -- the matches burning down close to his fingers before they fire up the cherry. And then leans back on his heels as he answers my question: "Is there any similarity between a criminal and an artist?"

"Both tend to have a sociopathic deviancy in their attitudes," he says, sucking on the stogie. "They don't see things like the average citizen. So to that extent, there is. Dustin even made that comment somewhere."

Bunker's referring to Dustin Hoffman, who played a version of Bunker in the 1978 Ulu Grosbard film "Straight Time." The movie was based on Bunker's first published novel, "No Beast So Fierce." Its protagonist Max Dembo is one of Bunker's alter egos.

Bunker's in the film as well, playing a different version of himself -- an underworld figure who meets Hoffman in a dark bar and plans a heist for him. According to Bunker's recently published memoir, "Education of a Felon," it's a role Bunker fleshed out in the late '50s when he spent most of his time concocting schemes for other criminals to enact.

"I was really good in that scene, man," says Bunker with a wicked little smile. "When they wrapped for the day, the whole cast applauded me. I've been in 20 or 30 movies since and never seen a cast do that. At the time, I had only been out of prison for six or seven months."

Bunker's bio offers an almost seamless melding of life and art. In brutal, uncompromising novels such as "Dog Eat Dog," "Little Boy Blue," "No Beast So Fierce" and "Animal Factor" (the subject of an upcoming Steve Buscemi-directed film starring Bunker and Willem Dafoe), the 66-year-old author has mined a wealth of experiences from his years in the underworld, on the lam and in the joint.

The scion of a broken home, he was in and out of juvenile detention facilities throughout his childhood -- mainly for truancy, thievery and escaping, which he did on several occasions.

Then, when he was 17, he drew a stint in San Quentin state prison, earning him the distinction of being the youngest person incarcerated there. It was the first of three terms, eventually totaling 18 years. Whenever he was out, L.A.'s street life lured him into a career of robbery, fraud and various other offenses, and soon enough, he'd be back in the joint.

But San Quentin was, strangely enough, the place where Bunker began to transform himself into the American Jean Genet, and it's where he did most of his serious reading.

"My library day was Saturday," he writes in "Education of a Felon." "We were allowed to have five books checked out at one time. I tried to read all five in seven nights, so I could get five more. I was no speed-reader, but I had six hours every night and half an hour in the morning. Sometimes if I was entranced, as with [Jack London's] 'The Sea Wolf,' I came back to the cell after breakfast."

Prison is also where he had the epiphany that he wanted to be a writer -- his inspiration coming from another cell-bound ink-slinger, Caryl Chessman, aka "The Red Light Bandit," whose death-row memoir made him a cause celebre in the '50s.

Bunker was in isolation, near Chessman on death row when Chessman, knowing Bunker liked to read, sent him over a copy of Argosy magazine via a guard. The mag had excerpted the first chapter of Chessman's "Cell 2455, Death Row," and after Bunker read it, he thought, "Why not me?"

"More than inspiration, it was revelation," Bunker states, pausing before a framed poster from the 1985 film "Runaway Train," for which Bunker co-wrote the screenplay. "It's what I wanted to do, and it was something I could do no matter what my condition. I didn't have any idea it would take 17 years and six books to get published."

Bunker's literary ambition rescued him from the cycle of recidivism, and he's been out of jail for 25 years. Not only does he enjoy the fruits of bourgeois affluence -- a charming, attractive wife, a well-mannered 6-year-old son, a house right out of Better Homes and Gardens and two sports cars (a brand new BMW and a classic '78 Alfa-Romeo); in addition, Bunker's the recipient of high literary praise from the likes of

James Ellroy, who calls him "a true original of American letters." And William Styron writes in the introduction to Bunker's memoir that Bunker is "one of a small handful of American writers who have created authentic literature out of their experiences as criminals and prisoners."

"I fought the law and the law won," goes the refrain. Bunker reversed that, beating authority at its own game -- subverting the status quo by crafting art from the penalties imposed upon him. As Bunker puts it in his memoir, "A lotus definitely grows from the mud."

"My relationship with the world changed," Bunker says. "When I got out of prison, I had not found God or anything. I had been in and out so many times and failed so many times and had [negative] attitudes about making it. Being a published writer changed all that."

If it hadn't been for his talent and drive, things might have been different.

"At one time in prison, I wrote over 200 letters for a job and didn't get an answer," he says. "I don't mean 'kiss my ass' or 'suck my dick' or 'fuck you, convict.' I didn't get a reply -- from nobody. I mean, the social contract has to work two ways."

The hardships and brutalities Bunker underwent in the pen fed right into the gritty realism he's known for. Unlike his great friend James Ellroy who "makes everything up," Bunker says he makes nothing up: "It's all taken from memory or experience or someone else's stories."

Even the bit parts he gets in movies not drawn from his life or fiction overlap his own history with an eerie irony. It was his cameo as Mr. Blue in the 1992 Quentin Tarantino film "Reservoir Dogs" that brought Bunker to the attention of Gen-Xers. In the film, he was part of a gang of hardened jewel thieves -- once again, a role for which Bunker had ample real-world preparation.

Would Bunker have become a writer, much less a celebrity, if he hadn't been in prison?

"Who knows?" wonders Bunker. "I loved to read. I read as an escape from the misery of my existence. But you don't know what you would have been. You go back and say, 'If I hadn't done that, I wouldn't have been this.' Well, I wouldn't have been me. There are other things I have an inclination for -- I have a natural affinity for the law, for the logic of it. I learned it easier than anything in the world."

However, being an ex-con still carries a stigma, even for a renowned novelist. Bunker points to the controversy surrounding convict Jack Henry Abbott, author of "In the Belly of the Beast." Abbott became notorious in 1981 for stabbing a waiter to death in New York's Greenwich Village after Norman Mailer had worked to secure his release from prison.

"That maniac-rat!" Bunker exclaims. "After that, every schlock TV series in the country had an episode with a convict-writer. I'm the only other one. Who else is there? It really did me a lot of damage. It still does. A lot of people can hide the fact they've been in prison. How can I hide it? It's part of my reputation."

Does Bunker still have problems with authority? Does he miss the adrenaline rush of breaking the law?

"Sometimes," he smiles. "But I can't punch people. They'll sue me and take money from me. If I ever start to miss the rush, I immediately remember the courtroom and the joint on top of that. No persons over 40 are heavy thieves. You burn out. The guy may have done things wild when he was young, and he may be a habitual criminal. But he doesn't do the same things. He becomes a shoplifter or a petty thief. Hard crime is a young man's game ... Once you're locked up, you're locked out. It's almost impossible to do what I did."

About this time, Bunker's young son appears in the doorway of the office, ball in hand, to ask his dad to play. Bunker's eyes light up as he tells him he'll be there in a minute.

No, Bunker will never return to the transgressions of his past. The social contract has finally worked, for him at least. Now he has far too much to lose.

Shares