There was a challenge to public mores Wednesday as a Senate committee listened to testimony about the marketing of violent entertainment products to children. But it wasn't because of Eminem's misogyny, sicko kids like Dylan Klebold or even Hootie and the Blowfish's second album. Rather, the horror came from both politicians and entertainment executives who indicated -- in their own distinctly charmless ways -- their utter cluelessness and alienation from the American public at large.

The hearings were an attempt to shine a light on the Federal Trade Commission study that concludes that film, music and video game products -- ones that the entertainment companies' own labeling systems judged to be inappropriate for children -- were being directly marketed to children.

But what if you held a hearing and nobody came? Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., chairman of the committee, almost found out the answer to that question when executives from the motion picture industry didn't even bother to show. With venom-spittle showering the chairman's microphone, McCain noted the "uncanny coincidence" of the fact that "every single studio executive was either out of the country or unavailable."

"I've only been on this committee for 14 years, and I've never seen such a thing," he said, attributing it to "hubris." McCain announced in his opening statement that he was convening an additional hearing in two weeks, demanding that today's absentees attend. He even called out luminaries like Walt Disney's Michael Eisner, News Corp's Rupert Murdoch and Viacom's Sumner Redstone by name.

In addition to the studio execs' collective no-show, McCain seemed to be most fired up about the FTC report's account of a studio putting together a focus group of children 11 years old and younger to see how best it could market an R-rated movie.

Even Motion Picture Association of America president Jack Valenti had to take umbrage at that. But Valenti was generally there to defend the indefensible. Justifying the film executives' absence with explanations that they were very, very busy, Valenti did agree that "it appears from the report that some marketing people stepped over the line." But in general, the old codger represented the industry, seemingly arguing against the very ratings system he supervises.

"When we draw lines in the creative world, those lines are ill-illuminated and hazily observed," he said. "This isn't Euclidean geometry, where the equations are pristine and explicit. These are subjective judgments." When asked about the FTC report's "Mystery Shopper Survey," which indicates that underage kids could get into R-rated movies almost 50 percent of the time, Valenti made a Clintonian distinction between movies with a "hard R" rating and a "soft R" rating, which did little to reassure the committee that the motion picture ratings worked.

"In our ratings system, we don't say anything's 'unsuitable,'" Valenti said. "We say it's 'inappropriate' ... A parent makes that judgment ... It doesn't mean you can't go."

Valenti was just one of many entertainment voices that didn't seem to get how damning the FTC report's conclusions are. FTC Chairman Robert Pitofsky urged greater self-regulation so as not to step on First Amendment issues, but he did leave the door open to considering legislation if Hollywood doesn't shape up, much less show up.

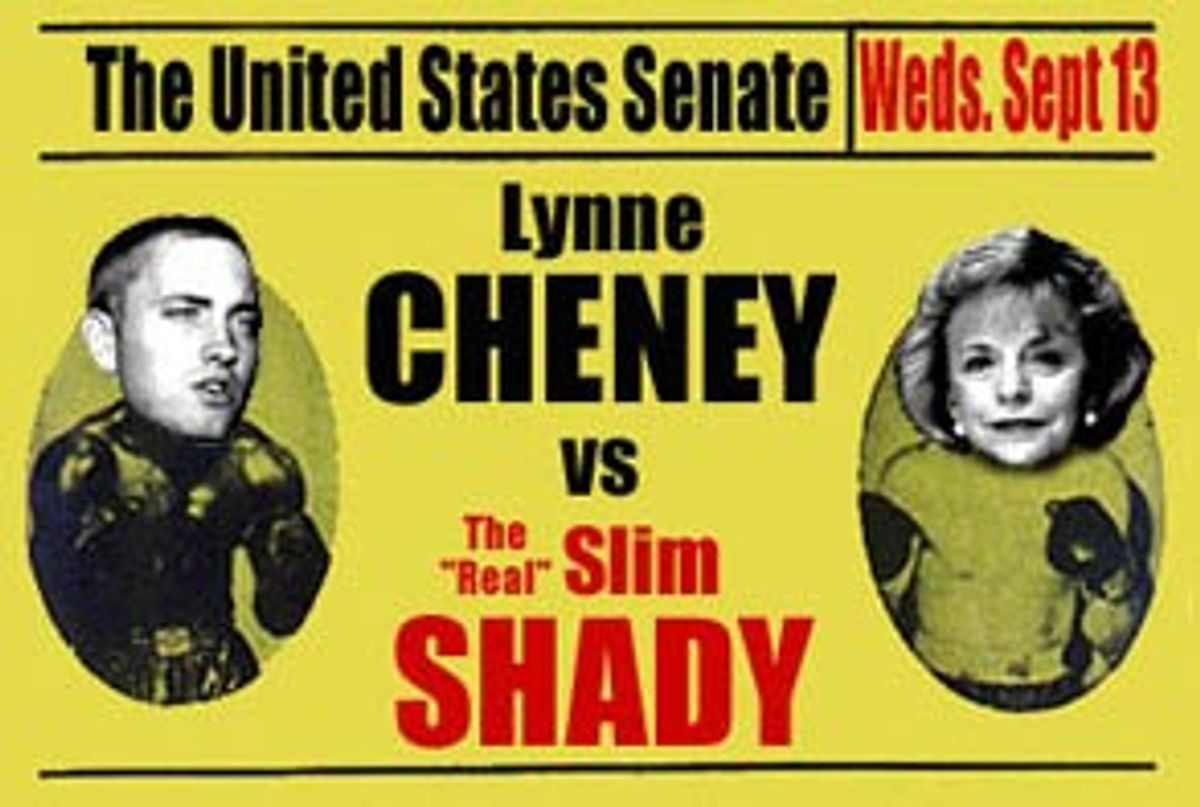

But even among the folks who showed up -- namely the politicians -- there was something missing. Most egregious and alarming was the absence of any serious thought or thorough research in the seemingly ad-libbed remarks of Lynne Cheney, former chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the wife of GOP vice presidential nominee Dick Cheney.

Campaign workers for Cheney's hubby -- and his boss, Texas Gov. George W. Bush -- hurriedly called McCain staffers over the weekend, eager to insert Cheney into the witness list. They were apparently worried that Democratic vice-presidential candidate Sen. Joseph Lieberman, D-Conn., who also testified -- being that he was one of the original co-sponsors of the Senate bill that called for the FTC study to begin with -- was helping Gore steal the Hollywood-bashing high ground where many of the swing voters the Gore and Bush camps are competing for seem to dwell. McCain acquiesced, even going so far as to say that the invitation had been his idea, which one might observe is not quite "straight talk."

Be that as it may, Bush headquarters must have been dismayed with Lieberman's headlining testimony. "This practice is deceptive," he said, "and I believe it is outrageous, and I hope it will stop." Nor could Austin have been pleased with Lieberman's rock-star treatment, especially the image of his warm embrace of his pal McCain. The hug was no doubt sincere -- the two are friends, and Lieberman was quite concerned during McCain's recent bout with cancer. But the warmth and intensity of the bear hug rivaled only that of the PDA the world saw at the Democratic Convention between Vice President Al Gore and Tipper, minus the spit-swapping. Not quite what the Bushies were looking for.

Still, Cheney poisoned the bipartisan spirit of the hearing with a sloppy accusation about a movie I doubt she's even seen, and by making a snarky remark about Gore and Lieberman's anticipated attendance at an entertainment-related Democratic National Committee fundraiser in New York on Thursday evening. The Gore-Lieberman simultaneous Hollywood bash/shakedown is a legitimate question to raise, but the Senate hearing was an inappropriate setting, and after the Lieberman-McCain slow-dance, it just looked bitter and nasty.

Which, at least, was consistent.

After declaring herself to be the anti-Eminem, Cheney snarked that Gore and Lieberman should take Miramax's Harvey Weinstein to task for the film "Kids" when they see him Thursday night. Cheney implied that director Larry Clark's "Kids" -- a movie marketed to adults -- condoned prepubescents engaging in violent and sexual activities. A release Wednesday from the Bush campaign said that "Kids" "showed young teenagers -- 13 and 14 -- having sex, participating in rape, smoking pot and assaulting strangers."

But "Kids" didn't glorify that behavior, it condemned it. The movie's message was too many members of Generation Y are being lost to us due to absent adequate supervision and a flurry of destructive and pernicious media influences.

As Richard Corliss wrote in Time magazine, "In 'Kids,' kids have easy sex; they have potent drugs; they seem to have total freedom from parental discipline. What they don't have is fun. Screwing around has become mandatory, and thus joyless, like house chores or homework. A truly radical, dangerous movie about teens would show the lure of the wild life while avoiding the twin tones of sensationalism and sentimentality. Clark's film doesn't do that."

Additionally, Roger Ebert called "Kids" "the kind of movie that needs to be talked about afterward. It doesn't tell us what it means. Sure, it has a 'message,' involving safe sex. But safe sex is not going to civilize these kids, make them into curious, capable citizens." The kids the film depicts, Ebert writes, "represent a failure of home, school, church and society."

So either Cheney never saw the film or she completely missed the point of it. (Which might be a matter for a second Senate hearing: Should the MPAA be held responsible for content that individuals like Cheney either don't see or don't understand?) It was easy to see that Cheney's whole process had been rushed. She bragged about a faux-creative idea of putting her protest of Eminem's misogynistic lyrics into letters to the two female members of the board of the Seagram Company, which owns Eminem's label, Interscope.

But "The Marshall Mathers LP," which Cheney said she was offended by, was released on May 23. Cheney's letters to the Seagram executives were dated Tuesday, Sept. 12, the day before the hearing.

So not only was it a gimmick; it was hastily conceived, the worst kind of bandwagon politics. And it was not unlike Gore's on-again, off-again condemnation of the excesses of Hollywood, which apparently becomes top priority when he's talking to soccer moms in Ohio, but disappears when Gore is among Armani-clad producers in Malibu, Calif.

But Cheney's wasn't the only ignorance on display for the crowd. The artistic community provided plenty.

Indeed, most of the members of Congress who testified -- including Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass., Rep. Henry Hyde, R-Ill., Lieberman, self-described "occasional songwriter" Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, and Sen. Chuck Hagel, R-Neb. -- generally stuck to the larger, disturbing points raised in the FTC report.

While most were quick to say that Hollywood wasn't the only guilty party, hardly any of them even mentioned the ease with which kids can obtain firearms in this country. McCain veered once or twice too often into his whole campaign-finance, soft-money-is-evil shtick, but for the most part the senators were on sturdy ground, armed as they were with the FTC's methodically culled data.

The data didn't do the most damage, however. Sen. Sam Brownback, R-Kansas, effectively displayed harsh lyrics by Eminem, Dr. Dre and the Ruff Ryders, a stark example of a product seemingly inappropriate for kids' consumption. Read one Dr. Dre work Brownback had blown up and matted (and censored, a tad):

I know yo type, so much b**ch in you/If it was slightly darker, lights was little dimmer/my d**k be stuck up in yo windpipe/Hmm, you'd rather blow me than fight/I'm from the old school, you owe me the right to slap you,/like the b**ch that you are/Youse a b**ch n**ga, motherf****n b**ch n**ga

There was little for the entertainment execs to say, especially since none of them seem able to understand why any parent might find it disturbing if his or her child was singing the delightful Gershwin-esque tune above. Just as the senators repeatedly tried to show they weren't complete book-burners by incessantly listing "Saving Private Ryan," "Schindler's List" and "The Patriot" as films they deemed OK, almost all of the entertainment executives pointed out that they, themselves, had kids. Attempts by both sides to prove their humanity with these stats fell as flat as that Vanilla Ice movie.

The outspoken Danny Goldberg of Artemis Records and the buttoned-down Strauss Zelnick of BMG Entertainment clung to the First Amendment like "Peanuts" character Linus to his security blanket, decrying the encroaching "censorship." (Zelnick was joined by his lawyer, Clinton attorney David Kendall, present and accounted for whenever Washington discusses bitches and hos.)

Goldberg elicited chuckles -- and a shocked expression from Sen. Ernest "Fritz" Hollings, D-S.C., himself no stranger to offensive expressions about minorities -- when he said that "Americans who are offended by curse words ... have no moral or legal right to impose such a standard on my family or the millions of other Americans who, like George W. Bush, are comfortable with cursing." He went on to argue that what may be inappropriate for one 14-year-old, as supervised by his parents, may be perfectly fine for another -- completely ignoring the point of the FTC study's larger thesis.

It wasn't entirely Goldberg's fault. After McCain temporarily left the room to go vote -- and Brownback and Sen. Byron Dorgan, D-N.D., were left alone -- the focus of the hearing quickly veered from the FTC report and focused instead on the most heinous examples of today's rap. Even after McCain returned, the larger issue of general filth kept rearing its head. Members of each side seemed more at ease in the comfort of their preassigned roles of Smut-Peddlers vs. First Amendment Shredders --

Maybe the FTC report itself was too complex. Or maybe it simply allowed neither side to score the easier layups.

In an attempt at his own "Have you no shame?" moment, Brownback pushed Goldberg and Zelnick to list "any image or word you would not put forward." Both executives insisted that they came across material that their consciences kept them from marketing, but they wouldn't submit to Brownback's insistence on a list of subjects.

"The responsibility lies within my company; it doesn't lie here," Zelnick said. "Are there things we would not put out? You bet there are."

The afternoon droned on. Some of the video-game industry executives raised serious questions about the FTC's data -- arguing, for example, that it's unfair that the report categorizes "The X-Files," "The Simpsons" and "Baywatch" as children's programming, since most of those shows' viewers are over 18. Peter Moore, president and COO of Sega of America, Inc., pointed out that one gaming magazine that the FTC report suggested was inappropriate as a venue for advertising for "M-rated game titles ... has over half of its readership aged 17 or older."

One of the few people who actually knew what he was talking about, Michael Eric Dyson, tried to illustrate how rappers like Master P, the Notorious B.I.G., Tupac Shakur and Snoop Dogg "highlight undervalued problems." Surely Dyson is the only one to cite the Notorious B.I.G.'s "Me & My Bitch" in Commerce Committee testimony. His knowledge and cadence not only livened up a stuffy hearing; he also provided a voice for rappers, surely under-represented at a hearing that talked about rap quite a bit.

Quite often, however, it came back to Brownback's question, the general accusation that -- as Kerry put it in one long, ponderous, Kerry-esque digression -- "some of the most highly respected corporate entities in the world" were marketing stuff that the committee found icky.

"I'm pretty open-minded, and pretty willing to accept anybody's right to be edgy and sometimes over the edge," Kerry said, but there were lyrics that he found to be without artistic merit even stretching that point.

To this, Recording Industry Association of America president and CEO Hilary Rosen argued that some people found lyrics he didn't like entertaining.

"Lots of things are entertaining," Kerry replied. "But they're not always allowed by law."

Dum-Bum-BUMMMM!!!

After more Kerry-Rosen coffee tawk, an irascible McCain got fed up, interrupting to remind them all that "This hearing is about marketing," not content and censorship. Finally, after more back and forth indicating that the entertainment folks weren't willing to cede a point, as the hearing reached its interminable sixth hour, McCain hammered it to a close, reminding all that the film executives were to be there in two weeks -- or else.

What did it all mean? To Goldberg, at least, not much. Hollings began his testimony by recalling previous years' hearings -- not to mention studies -- that addressed the same issue, and after the hearing, Goldberg had the resigned, carefree air of someone who knows that none of the senators' threats will amount to anything.

When asked if he was worried that the report and Wednesday's hearing could result in legislation, Goldberg replied with an emphatic "no."

"I don't feel threatened. I'm not a lawyer, but it seems like an awfully unlikely scenario to me."

Shares