At 9:55 p.m. on February 27, 1991, an inmate named Richard Danziger at a Texas prison near Amarillo was brutally assaulted by another inmate, who threw him to the ground and kicked him in the head repeatedly with his steel-tipped boots. Danziger was taken to a nearby hospital where emergency surgery was performed and part of his brain was removed. The other guy, Armando Gutierrez, was serving an 18-year sentence for assaulting a police officer, and had an additional 25 years put on his sentence for nearly killing Danziger. And as it turns out, Gutierrez had thought Danziger was someone else entirely. He'd jumped the wrong man.

So too, it now appears, did the State of Texas. Two of them, in fact.

At the time Danziger was attacked, he and another man, his onetime roommate and friend, Christopher Ochoa, were serving life sentences for the brutal 1988 murder of 20-year-old Nancy DePriest, the mother of a 15-month-old baby girl. According to the sordid testimony in Danziger's trial, the two men repeatedly raped De Priest at an Austin Pizza Hut where she was working, including twice after she'd been shot in the back of the head.

Now a third man, Achim Josef Marino, insists he -- not Ochoa, and not Danziger -- raped and murdered DePriest. And one DNA test showed that DNA evidence discovered on DePriest did not match Ochoa's or Danziger's. It did, however, match Marino, who is serving a life sentence for aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon and a handful of other felonies. Sources close to the investigation confirm that there is no evidence that Danziger or Ochoa ever met Marino.

Marino says he has been trying to come clean for more than four years. As reported by Salon, Marino sent a letter to Texas Gov. George W. Bush two years ago confessing to the crime, and insisting Bush was "morally obligated" to notify attorneys for Danziger and Ochoa. Bush's office filed the letter away, but apparently notified no one, not the lawyers for Danziger or Ochoa nor the police nor the district attorney.

Bush's office might not have been the only one to ignore Marino's plea. Marino says he wrote to Bush because earlier confessions sent to the police, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Austin American-Statesman had failed to elicit any response. Ochoa's attorneys provided Salon with a copy of a six-page letter, dated Feb. 5, 1996, that Marino says he sent to the Statesman. In it he confesses to the rape and murder of DePriest.

He also, in digressions, writes of how he'd been "possessed by a spirit" that appeared to him as "a serpent dragon type of animal" when he was a child. He discusses his hatred of his mother while growing up -- trying to kill her on one occasion -- and how he emerged in 1988, after five years in prison, hating "people in general, and women in particular." Eventually, Marino circles back to his main point, insisting that he was writing the American-Statesman for "Danzinger and Ochoa sake" [sic] and, as he did in his subsequent letter to Bush, he appealed to the paper to contact their lawyers.

The police, it turns out, did look into Marino's letter in March or April 1996, according to sources familiar with the investigation, and appear close -- four years later -- to completing an investigation that might free both Ochoa and Danziger. Sources also say that assertions Marino makes in his letters -- that keys from the Pizza Hut and two bank moneybags from the restaurant could be picked up from his parents' home -- have also proven true.

This comes amid a major review by the police and Austin district attorney of 400 cases prior to 1996 -- when DNA testing began being regularly used in trials -- to see how many may have resulted in wrongful convictions. (Earlier this month a Texas judge recommended that a man who had served 16 years in prison on a rape conviction be released after DNA evidence exonerated him). It also coincides with a presidential campaign starring a Texas governor who has repeatedly defended the quality of the Texas criminal justice system, insisting its use of the death penalty under his watch has been error-free.

Bush's only comment on this particular matter, to ABC News: "Marino's case was fully looked at by the Austin police department." Perhaps. But the issue is not "Marino's case" but the cases of two ostensibly innocent men Marino pleaded with the governor -- unsuccessfully -- to address. The reexamination of those cases, by all accounts, is expected to lead to a completely different conclusion than that reached by police nearly 12 years ago.

Looking back on the Danziger/Ochoa trial, Robert A. Perkins, the presiding judge, insists that "any jury hearing that testimony would have found those two guys guilty." Now it looks like Danziger and Ochoa may turn out to prove that even a case that seems error-free can wind up dead wrong.

Ochoa and Danziger had met at the Austin Pizza Hut where they both worked, not far from the one where Nancy DePriest was employed. They were picked up a day after toasting DePriest's memory at the Pizza Hut where she worked, according to Danziger's trial record. Employees at the restaurant, finding their behavior odd, called and reported it to the police.

Three days later, Christopher Ochoa, 22, confessed to the crime, and he became the state's star witness against his friend and co-worker, Danziger. Judge Perkins describes the testimony by Ochoa as "very compelling." Not only was it emotional, but it contained details police said only a witness to the crime could have known.

Now, Ochoa and his lawyers insist that his confession and his testimony were a fabrication coerced by police who had given him a Hobson's choice. "He was made to feel that he was doomed one way or the other," says Keith Findley, a lawyer with the Wisconsin Innocence Project who is working on the case. "His doom could either be death or it could be [life in] prison."

But with a life sentence came another ugly reality. The police were convinced that Ochoa and Danziger had committed the crime together, and in exchange for avoiding a death sentence, Ochoa had to take Danziger down with him. "That was part of the plea bargain. He had to testify against Danziger," Findley said

Danziger always refused to plead. He maintained his innocence throughout his 1990 trial, insisting he had no idea why Ochoa implicated him. The homicide detectives who testified against him were lying, he said. Ochoa maintained his innocence in conversations with family members; his attorneys say he would not assert the claim publicly for fear the state would try to execute him.

"He said 'They made me confess and how am I going to prove my innocence now? It's my word against theirs,'" says Ronald Navejos, Ochoa's uncle and closest friend.

But if Ochoa's confession and his testimony at Danziger's trial were all lies, where did he get the facts -- and the story line -- that allowed him to appear completely credible to the judge and jury? Ochoa didn't just say he and Danziger raped and murdered the victim, but described Danziger's elaborate plan for the robbery, such as how they planned to meet at a McDonald's near the Pizza Hut at 7 a.m. the morning of the murder; how they entered the crime scene by a side door using a key Danziger had obtained; their conversation with the victim, who was cutting pizza dough when they entered; and how the two men bound her, gagged her, raped and sodomized her eight different times.

Ochoa's lawyers say he got his story line and the key crime scene facts from the police. "There isn't any way [Ochoa] would have known the facts about the case unless they told him the facts about the case," says Bill Allison, an Austin attorney representing Ochoa.

Allison doesn't believe the police necessarily fabricated their case against Ochoa, but that they "violated every rule of taking down a statement that you can violate." Ochoa asked for a lawyer the first day he was interrogated but was denied one on the ground that he hadn't been charged with anything. "The invocation of asking for a lawyer should have stopped the interrogation at that point," says Allison, who claims the police were "feeding him [Ochoa] facts about the case" as they questioned him. Allison also alleges that a critical tape recording of Ochoa's interrogation, occurring just prior to the confession, has mysteriously disappeared.

Allison also likes to point out that the police sergeant primarily responsible for the interrogation, a man named Hector Polanco, "can be very intimidating." Polanco is a controversial figure who has been accused of coercing confessions from suspects in several other cases. In 1992, four years after Ochoa and Danziger were convicted, the Austin Police Department fired Polanco after an internal investigation determined he had presented perjured testimony in a murder trial.

Polanco was reinstated nine months later, by an arbitrator who attributed an alleged false statement in a murder trial to a memory lapse, and he later won a $350,000 jury judgment in a subsequent lawsuit against the department over his firing.

Ochoa told his mother, Dora Ochoa, and others in his family that Polanco threw chairs around the room during his interrogation. Ronald Navejos says Ochoa told him, "If he didn't confess they'd crush his head." His current attorneys also maintain that there were threats of physical violence. Meanwhile, Donna Angstadt, Danziger's former girlfriend, describes her questioning by Polanco and Sgt. Bruce Boardman as "the most horrific, the most horrible experience I've ever been through in my life. I had nightmares about this forever."

Angstadt was the manager of the Pizza Hut where Danziger and Ochoa worked. She says Polanco and Boardman tried to link her to the crime and threatened to have her children, then 9 and 4, removed from her custody. "They threatened that if Richard gets out, he's going to hunt me down and kill me like he did Nancy DePriest ... . They told me Richard had told Chris [Ochoa] that I'm the one who supplied the gun. Another time, Hector Polanco said, 'Your boyfriend's holding her head and you're the one who pulled the trigger for your little love interest.'"

Polanco, who is on medical leave, could not be reached. Boardman refused to comment. A source close to the investigation into Marino's claims said neither man is a subject of the current inquiry, in part because the statute of limitations would have expired on any crime they might have committed in exacting a false confession from Ochoa in 1988.

Still, if the police did coerce Ochoa into confessing a crime that Marino committed, as Ochoa's lawyers now assert, that means Ochoa is guilty of fingering another perfectly innocent man -- his friend, Danziger -- to save himself. It's a prospect, says Danziger's sister, Barbara Oakley, that haunts her and her family. "To be very honest with you, we're very, very angry," she says. "We'd like to meet [Ochoa] and know why he did this. He and Richard were supposed to be friends. I can understand, as far as he's concerned, his making a false confession. But why did he implicate my brother? Why? Why? Why not John Doe? And why hasn't he tried to contact us or his family members and tried to say something? He knows my brother's been hurt. Why not come forward after all these years?"

Today Oakley describes her brother as extremely nervous and fearful of having anyone stand or even walk behind him. "He's very intimidated. He doesn't want anyone messing with him," she says. "He's like that the entire time you talk to him." She says the last time she visited her brother, he continually mistook Oakley's daughter for Oakley. Danziger has been confined to the Skyview psychiatric prison in Rusk, Texas, since March 1997.

If the Austin police were prepared to intimidate someone into coercing another suspect, Bill Allison says they picked the perfect subject in Ochoa. "I tell you, I think in the first 15 seconds of seeing Chris Ochoa, they knew they could get him to talk. It's his demeanor. He's not a real strong person. He's small. He wasn't experienced."

Friends and family members describe Ochoa in similar terms. His mother, Dora Ochoa says, "He was a timid little boy" who dreamed of being a baseball player or a priest. His uncle, Ronald Navejos, described him as "a smart kid, but a real loner. I tried to pull him out of that by taking him out and doing things with him. But he was real quiet."

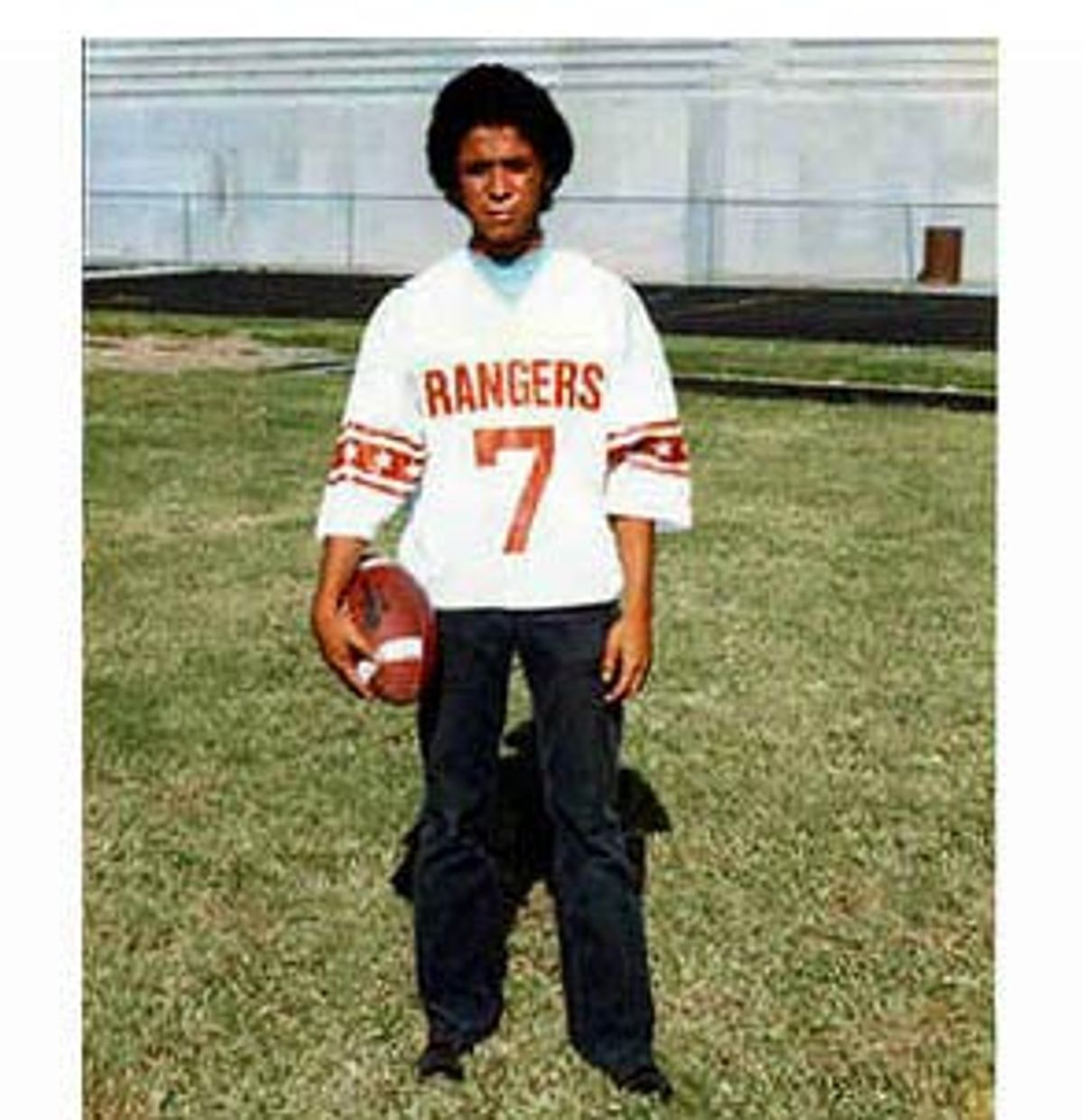

Ochoa's background provides nothing that comports with the profile of a cold-blooded murderer. He grew up in a tightly knit, third-generation, churchgoing Mexican-American family and graduated in 1984 with honors from Riverside High School in El Paso.

He was manager of the Riverside football team, but a fellow team member, Andres Martinez, says Ochoa didn't fit the macho, football player stereotype. "He wasn't hanging out with the rest of us off the field," says Martinez, now a truck driver who lives in Chaparral, N.M. "We were the rowdy bunch and Chris was very quiet. He kept to himself."

Ochoa's temperament seemed better suited to Riverside High's literary magazine, where he was one of the editors. To this day, he writes songs and poems to friends and family members. A handful of these, provided by his mother, suggest an understandably bleak, suffocating outlook on life. In one song, "Walkin' in the Dark," he writes that "hopes and dreams are no longer with me/There's nothing left for me to say/Gone is my imagination and inspiration." In another song, he writes: "I look for my future somewhere/ It's so dark out there I can't see/Don't see it as hard as I stare."

Ochoa has now spent about a third of his life in two medium security Texas prisons, first at Coffield Prison near Tennessee Colony, and for the last two years at the state prison in Huntsville. According to his uncle, Navejos, Ochoa was "shocked" and "really didn't know how to handle" his incarceration at first. Navejos says there was a time when he believed Ochoa was depressed and had given up hope. "He thought he was going to die there. I kept telling him to keep his faith up, to try to keep positive thoughts in mind."

He says Ochoa has been on good terms with the warden and has had his "good conduct" rewarded with decent jobs, most recently in the prison's shipping and receiving unit. Ochoa's mother claims her son has received two college diplomas while in prison, one in business administration and another in computer science.

Navejos says he "never doubted he was innocent because I know Chris, and I know what he is capable of. He was too timid to do something like this." He also, Navejos and Dora Ochoa say, has never mentioned Danziger to them.

Before the prison assault that left Richard Danziger severely brain damaged, Barbara Oakley says her brother was "a very happy, very loving individual who always found something to laugh about."

Although his childhood was hardly predictive of a future life of crime, Oakley says it was also no picnic, in part because his parents, who were in the military, were always moving around, and in part because they went through a "nasty divorce." As a teenager, Danziger was sent to Brown Schools in San Marcos, Texas, which specializes in services for troubled youth and juvenile offenders, where he reportedly received psychological treatment. (At his trial Danziger told jurors he didn't want them to conclude from this experience that he was "some psycho or some lunatic," an assurance that likely had just the opposite effect.) When he was arrested in 1989, Danziger was on parole for forging one of his mother's checks. Oakley says she didn't think her brother had many friends at the time other than Donna Angstadt and Ochoa.

Oakley says her top priority now is getting Danziger released and getting the state of Texas to pay for his care for the rest of his life. She says she would like to have her brother released soon so he can see his mother, who is dying of lymphoma.

Although the Austin police seemed to give little credence to Marino's confession until recently, it is safe to say that without it, Danziger and Ochoa would have practically no hope of ever being released. Why it has taken so long to get to the bottom of Marino's claims is not at all clear. Police approached Ochoa sometime in 1998, says attorney Allison, but Ochoa didn't understand why. He assumed the police were trying to get him to confess to some unsolved crimes, the ostensible carrot being that his cooperation might lead to parole.

"You don't get parole by claiming you're innocent," Allison says.

Danziger was not even provided an attorney until two weeks ago, more than four years after police had Marino's first confession. And it was not until February of this year, under prodding from the Wisconsin Innocence Project, which had taken up Ochoa's cause, that the police and the Austin district attorney conducted DNA tests that had been unavailable at the time of Danziger's trial.

Attorneys who have been critical of the Texas death penalty and, more broadly, of its criminal justice system, think what happened to Ochoa and Danziger is significant for several reasons. One is that it suggests how the death penalty can be misused to intimidate an innocent person into making a false confession.

Secondly, perhaps obviously, a false confession perverts the entire judicial process. Prosecutors and jurors relying on perjured testimony are likely to produce a tainted verdict. "If in fact the two men are not guilty," says Travis County District Attorney Ronnie Earle, "it is a tragedy for everybody concerned. It is a tragedy for the two men involved and it is a tragedy for the community because of the general sense of justice that people in this community have."

One way of preventing abuses that lead to wrongful convictions is to provide sufficient money to pay competent defense lawyers from the time of arrest. But the state of Texas has been loath to finance full-time public defenders -- and Bush vetoed legislation that would have required the state to provide a lawyer within 20 days of an arrest. Most states provide attorneys within no more than three days.

While the Austin district attorney's current investigation of wrongful convictions has been roundly applauded by defense attorneys and may yet find some innocent people in Texas prisons, it is designed to look primarily at cases in which DNA is available. (Earle says other cases "might also be included.") No one in Texas is talking about reinvestigating cases in which defendants were assigned incompetent lawyers or no lawyers, or about convictions that resulted from potential police coercion or testimony by unreliable jailhouse witnesses. Innocent people convicted in those circumstances will probably just have to serve out their time.

But no matter what happens, nothing will give Richard Danziger back his health -- or restore the last 12 years of his and Ochoa's lives.

Shares