The best of reader submissions following our talk of airplanes and Hollywood...

"Hail Mary" (1985)

Jean-Luc Godard's retelling of the birth of Christ set in modern France. The angel Gabriel disembarks from an Air France jet to give Mary the news.

"Parallax View" (1974)

Roman à clef of the Kennedy conspiracy with Warren Beatty. A tense scene on a jet where Beatty's character must foil a bombing without giving away how he knows about it. Scene ends with beautiful shot of jet at Dulles trailing a plume of black smoke.

"The Killing" (1956)

Stanley Kubrick's masterful tale of a complex robbery and its aftermath, from a script partly written by Jim Thompson. When a slack-jawed baggage handler knocks Sterling Hayden's loot-filled suitcase off his cart, we watch as the cash gets blown across a nighttime runway.

"Bullitt" (1968)

Steve McQueen's dogged pursuit of a suspect leads him onto the runway at San Francisco, and directly into the path of a jet.

"Magnum Force" (1973)

Dirty Harry Callahan blithely impersonates a jet pilot to get aboard a hijacked plane and clean house.

"Dead Heat on a Merry-Go-Round" (1966)

The airport as its own intricate little world. James Coburn and gang plot to rob a bank at LAX.

"Midnight Express" (1978)

There's a jet waiting in Istanbul, and young Billy Hayes most assuredly won't be taking it back to America.

"The Rose" (1979)

Bette Midler is a '70s rock star with her de rigueur personal and personalized plane.

"Easy Rider" (1969)

Jet screaming over Phil Spector's head at LAX.

"La Jetée" (1962)

Chris Marker's photo-film features a protagonist obsessed with a childhood memory of Orly Airport.

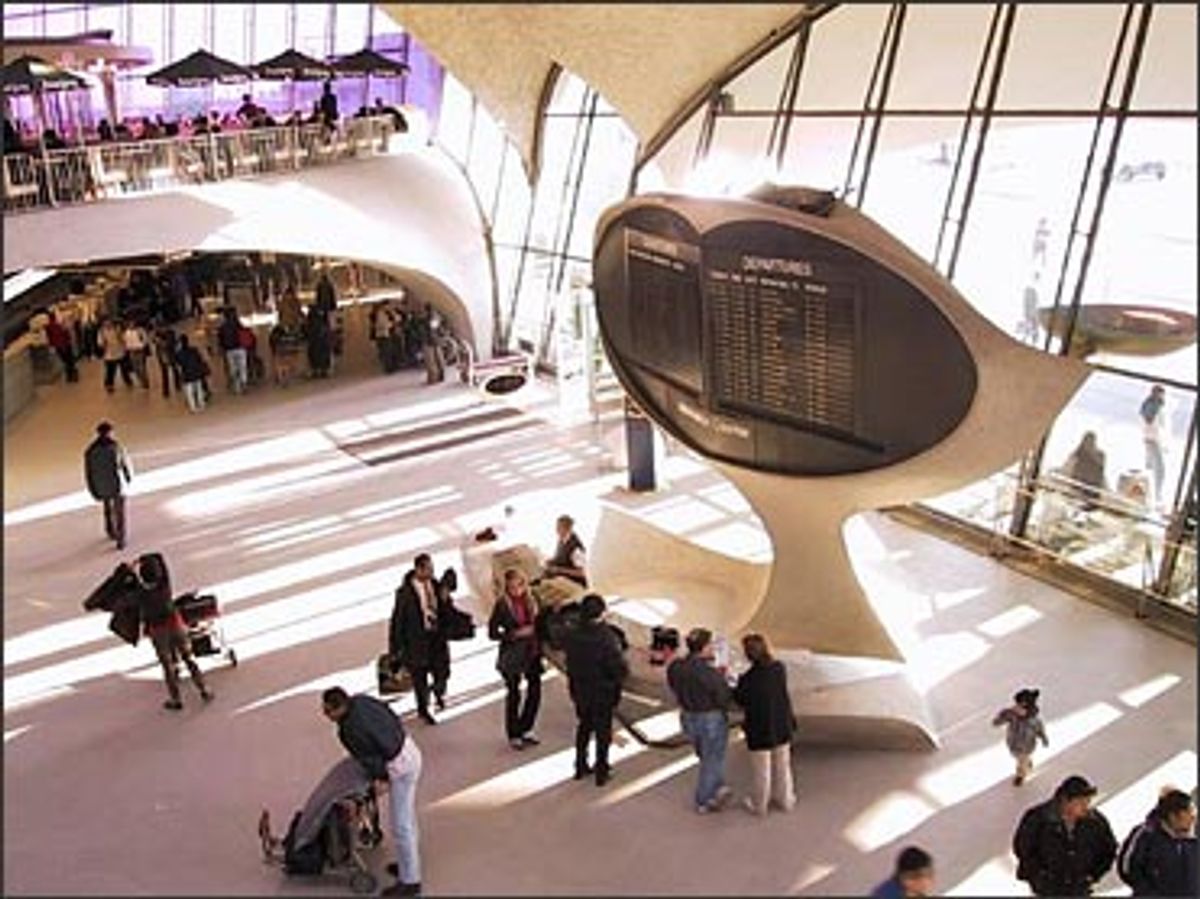

Pushing this in a slightly different direction, the new picture "Catch Me If You Can" was partly filmed at Kennedy Airport. More specifically, at Eero Saarinen's 1962 TWA terminal. For a movie trying to revisit the verve and glamour of the young Jet Age, this modernist masterpiece is the perfect backdrop.

Following the evolution of airport architecture through the 1960s, one notices a progression from bland utilitarianism to proud ideal and back again. The dawn of commercial flight gave us barns and wood-frame hangars, followed in the '30s by exalted structures built with the spirit and permanence of railroad terminals (pay a visit some time to Lunken Field in Cincinnati). But then as the number of passengers soared and airports required greater size and expandability, we saw a stricter, unimaginative deference to the lowest common denominators of cost control and ease of construction.

Such a statement is a bit disingenuous, as architectural language, of course, speaks to its time, and today's grimy hallways and soot-stained girders were yesterday's stunning achievements (St. Louis, anyone?). But the era of the concourse was born, and the airport ceased to exist as symbol or spectacle. Unfortunate, really, for as any lover of air travel will tell you: It's the departure, stupid.

JFK, known as Idlewild Airport until 1963, was and remains unlike most other large airports. Rather than rely on a central terminal or cluster of concourses, it has passengers board and deplane around a necklace of autonomous buildings. Each of these, at least in theory, was to incorporate some representative motif of their respective landlord airlines.

Saarinen's TWA, and the not-dissimilar spidery "Theme Building" at LAX conceived at the same time, became eccentric icons. Not necessarily because of their inherent innovation or uniqueness, but because they returned a sense of identity to the modern airport, a vitality that would lend itself in the years to come to a host of showcase facilities around the world.

Saarinen, who also built the Gateway Arch in St. Louis and the sweepingly beautiful central terminal at Washington Dulles, described his TWA design as "all one thing." The lobby is a fluid, unified sculpture of a space -- wildly futuristic yet firmly organic at the same time, overhung by a cantilevered ceiling rising from the center like huge wings.

In the mid-1990s I worked in that building -- based there with the commuter affiliate of TWA. Sometimes I'd sit in the second-story restaurant looking down into the lobby. I'd watch the people below -- the gangs of kids in sandals who neither cared for nor knew anything of the place, eyes locked on their copies of Details or Spin, waiting for final call to St. Louis or Rome or Tel Aviv. The terminal was a decrepit relic by then, undersized and dirty, with a sense of doom hanging in the air. Sparrows and starlings lived in the yellowed rafters and would swoop around grabbing up crumbs from under the tables.

But in the movie it looks great again.

Now unoccupied after TWA was subsumed by American Airlines, the structure's fate is being arbitrated between preservationists and Port Authority bureaucrats. To help the cause, try going here.

Anyway, if you're still not inspired and have some time to kill, go across Queens to La Guardia, where you can relish the gleaming deco doors of the Marine Air Terminal (1939), formerly the property of Pan Am and now directly adjacent to the Delta Shuttle. Inside the rotunda is a 360-degree history-of-flight mural and cutaway of an old Pan Am flying boat.

Which isn't to dwell too haughtily in the past, as some of the newest airport projects are among the most resplendent: Kuala Lumpur and Hong Kong, for instance, and the recently completed international terminal at San Francisco, the largest in North America. The latter's interior was described by one critic as "achingly boring," but the exterior façade, with its metal latticework and giant horizontal louvers, is nonetheless dazzling. Or, my favorite, British Airways' sublimely ultramodern World Cargo Centre at Heathrow.

On a smaller scale, how many of you have ever seen Roanoke Regional Airport in west central Virginia? Brick archways and exposed girders offer the look and personality of a renovated Blue Ridge warehouse. It's a pure faux, Applebee's style of down-home, but the effect is disarmingly comfortable. Much in the way Baltimore's Camden Yards works for baseball, Roanoke's retro works for airports.

But anyway, see how this happens -- art, architecture, geography, all pulled together? I once described the underlying gravity of air travel as "weepy culture bridging," but I think the point is simple enough to accept. My job isn't to bore you with stats or specs about the wingspan of a 747 (211 feet), but to draw in and appease a more general sense of curiosity. Is it working? Not sure what kind of crossover appeal I've got going, but trust me: There's more to airports than concrete and crowds, and more to airplanes than machinery and testosterone.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

I find it hard to believe the WTC hijackers, trained only as private pilots, were able to steer those 757s and 767s into their targets. Do you think they needed advanced training, and do you believe a foreign government provided this?

No, it doesn't shock me that the hijackers, with minimal experience, were able to accomplish what they did. Their feats did not require in-depth technical knowledge or skill. They were out of their league, obviously, but many private pilots would have little trouble handling the up/down/left/right of a widebody jet.

They needed some luck, and they got it, especially with regard to the Pentagon. Hitting a stationary target from above -- even a big one with five sides -- is very difficult. To make it easier, the hijacker pilot did not come directly in at a steep angle, but "landed" into the building as obliquely as possible. If he had flown the same profile ten times, five times he'd have ended up a tumble of wreckage short of the target, or else would have overflown it entirely.

Atta and at least one other hijacker did buy several hours of jet simulator training on a Boeing 727. This was not the same type of jet used in the attacks (757s and 767s), but it really didn't need to be. The simulator time was not supplied by a foreign state, but was purchased from a private flight academy in Florida.

What are those numbers and letters for on the back of every plane's fuselage?

That's the ship's registration, which like a car's license plate is displayed on the exterior of every plane. All U.S. registrations are prefixed with the letter N, followed by a sequence of numbers and, usually, letters. A United 747 registration: N184UA. Note that "UA" denotes United Airlines, but the letters don't always follow this rule. Next time you fly, jot down the registration, and using my reference materials I can tell you all sorts of, um, fascinating and sundry information about your plane, including its date of construction.

Other countries do it differently, some using only letters, only numbers or both. An Air France Concorde registration: F-BVFB. Often the prefix coding is intuitive, such as "G" for Great Britain, "JA" for Japan, and "D" for Germany. Others seem inexplicable, like Brazil's "PP," Belgium's "OO," and even our own "N." If ever you notice a really strange one, let me know and I can decipher it for you.

Registrations don't always change when a plane is sold, and occasionally a jet's numbers can give insight into its history. If you see an old 727 freighter with a registration ending in "AA," chances are it once flew passengers in the colors of American Airlines. Plane spotters use registrations to keep track of which aircraft they have and haven't seen (or at least they used to, until being banished from airports after 9/11). In grade school I had notebooks full of them.

Do crews eat the same terrible food as the rest of us?

Yes. Sometimes it's a coach meal, sometimes a first- or business-class setup, or maybe a little bit of each. Or, often enough, nothing, even when passengers are fed. It depends on the duration of the flight, and often there are contract stipulations covering a crew's culinary entitlements. One regional carrier was giving Subway sandwiches to its pilots on otherwise uncatered flights. And yes, to avoid food poisoning pilots are supposed to consume separate entrees when possible.

Honestly, I've never had a problem with airline food the way most people seem to. And in the forward cabins the cuisine is quite good. My issue is less with taste than with the often pretentious, excessive and wasteful presentation. In a typical coach-class meal, there is more plastic, in the form of cups and wrappers, than food.

Looking back at some career lowlights again: Among the greatest woes of flying turboprops at the regional level, in addition to making 14 grand a year, was the lack of access to food. When late or pressed for time, we were routinely denied meal breaks even during 10- or 12-hour stretches. To combat starvation, many of us brought our own food. There's a takeout place near Logan International called Spinelli's, which for a few years provided chicken parm sandwiches in exchange for most of my pathetic salary. I'd eat these in the cockpit on the way to Burlington or Baltimore or Montreal. Our turboprops had no door or curtain, and passengers would watch their captain sopping himself and his white polyester shirts with tomato sauce at 21,000 feet.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Do you have questions for Salon's aviation expert? Send them to AskThePilot and look for answers in a future column.

Shares