Forty years after Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton put Puerto Vallarta on the map, the resort's surroundings on the Bay of Banderas still contain miles of undeveloped shoreline -- where, as the brochures might put it, ravishingly beautiful jungle meets some of Mexico's loveliest beaches. Developers from all over the globe have driven prime beachfront prices north of Vallarta, in the state of Nayarit, to $800,000 an acre. But there are still bargains to be found to the south in Jalisco, where steep jungled mountains have preserved the coast's isolation since long before the Spanish came.

Most of this coast, from a few miles south of Puerto Vallarta to the tip of the bay at Cabo Corrientes, remains reachable only by boat. One of the smallest of the towns so accessible, less than an hour from Puerto Vallarta in a fiberglass panga driven by the biggest outboard motor the owner can lay his hands on, is an indigenous community named Pizota.

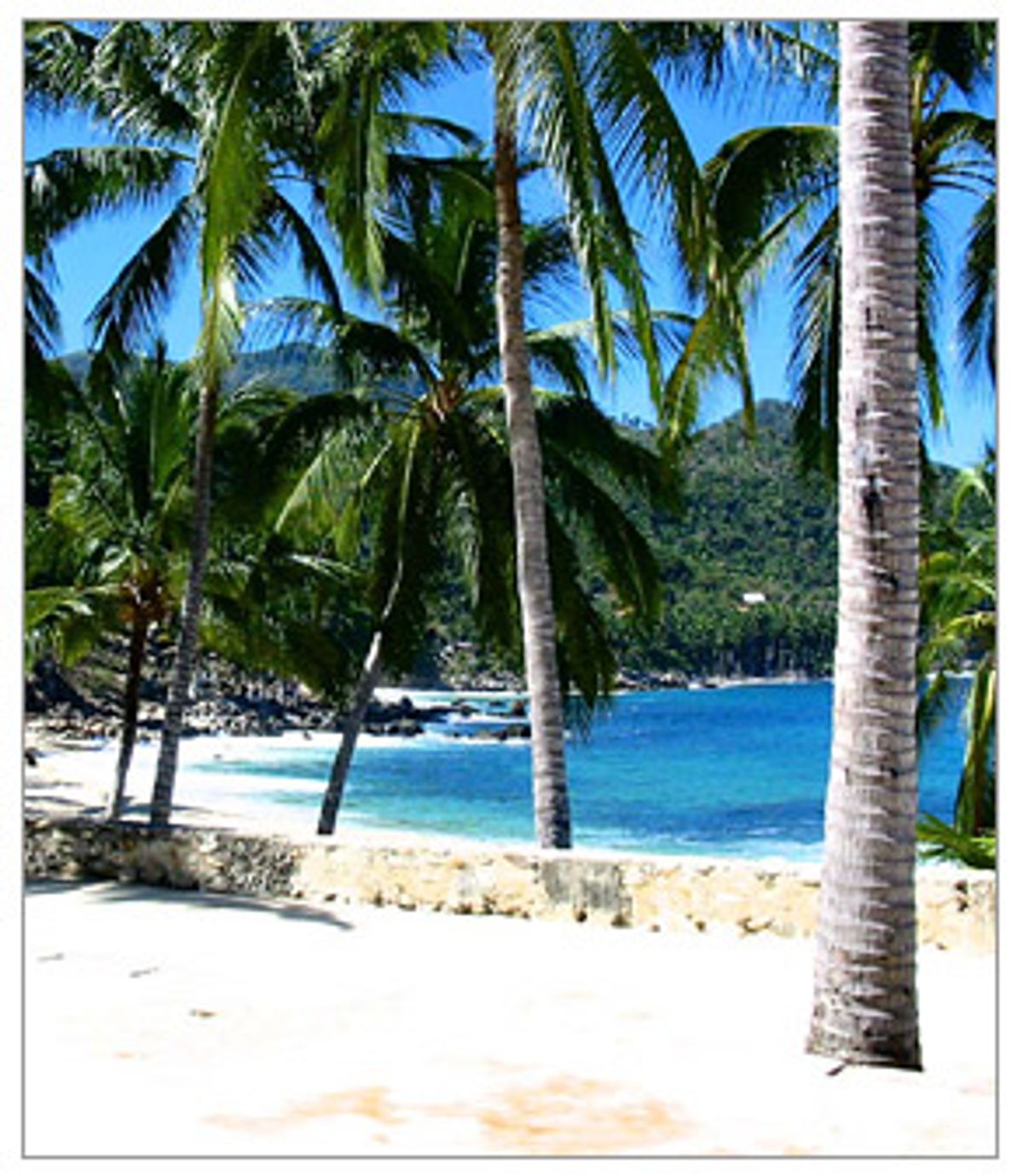

In Pizota, about 85 people live by fishing, a little tourism, and the odd job at some of the larger resorts up the coast. Pizota has no roads or cars, no grid-based electricity, no municipal water supply, no visible government. Its children go to a one-room school that stops at the sixth grade. It sits on about half a mile of prime beach with a drop-dead view of the bay and a psychedelic sunset every night. Therefore, predictably, this tiny hamlet is about to be switched into the global commercial network.

Last November, Pizota agreed to lease 250 acres of its best land, including the beaches, for 30 years to one of Mexico's most colorful entrepreneurs, Jorge Vergara Madrigal. Although his Guadalajara Chivas football team fields only Mexican players, Vergara is an enthusiastic participant in the global economy. Omnilife, his health products company, derives over a billion dollars annually in sales throughout Mexico, Latin and South America, and parts of Europe and the U.S. southwest. Vergara was also producer of 2002's Oscar-winning "Y Tu Mama También," an international hit, and the upcoming "The Assassination of Richard Nixon," starring this year's Oscar-winning Sean Penn. He plans a mammoth international cultural, sports and business center for the Jalisco capital of Guadalajara. Even his soccer empire is going global, with teams in the infant Major League Soccer organization in the U.S., and in Spain and Costa Rica.

According to word of mouth, Pizota's only means of communication, Vergara intends to use the land to build a resort solely for the use of his million and a half independent Omnilife distributors. It will be an ecological wonder of wood, bamboo and palapa capable of housing 1,200 visitors at a time and carrying away all of their waste and sewage, all without using electrical power and without access by road. (There's no small irony to Vergara's plans, as one of the subplots of "Y Tu Mama También" involved the displacement of local fishermen and their families by huge new seaside resorts.)

Omnilife refuses to say publicly what its plans are for Pizota, and the contracts it signed with Pizotans say only that it will build a tourist attraction, or engage in any other profitable activity not actually illegal. Should the project not work out, Vergara can walk away on a year's notice, or can sublet the property to a third party without Pizota's approval. For these rights, Vergara will pay a reported $300,000 a year, a fraction of the debt and legal obligations he would incur in buying land just a few miles up the bay.

If carried out, the project means that Pizota will never be the same, which is more or less OK with the people who live there. They are willing to trade land and serious poverty for what looks like a lot of money and, they hope, jobs at the resort. Having experienced the noise and pollution of Puerto Vallarta, they also realize that they are giving up the choicest part of their existence, the tranquility, beauty, and seclusion of their surroundings, to become a small part of a bustling company town. They can only guess how that will work out. They have become, in a sense, an outpost on a kind of frontier between the global network of finance and business and their uncharted local world.

This frontier is constantly shifting, and the development of Pizota now depends completely on the global economy -- on how well Omnilife distributors flog their product, on whether or not Sean Penn retains his box office draw, on the Chivas' place in the league standings, and on the difficult progress of Vergara's huge Guadalajara project, now six years in the planning and still barely started.

But even though in this sense the deal is something of a crapshoot for Pizotans, they are needy enough to risk their land on a link to the global economy, and innocent enough to think they have a chance of winning. Locally, their initial stake of $300,000 will go a long way. There is already some new building, and new and more powerful outboards have appeared on some pangas. There are rumors of a new school and a clinic, restaurants, and even a zoo, courtesy of Vergara. Other nearby villages expect to share in the jobs Omnilife will provide. I asked one Pizotan who now has to work outside the town if he felt the project would really develop. "I hope so" he said; "there's nothing else for the people here." Vergara's force-fed tourism may give the often grim visage of globalization a more benign local face.

Although its inhabitants are largely mezistado (of mixed Indian and Spanish ancestry), Pizota remains a true indigenous village, part of a larger indigenous community called Chacala that holds title to some 50,000 acres in the southern part of the bay through a 16th century charter from King Philip II of Spain that is still recognized in the Mexican Constitution. The people have lived on this land for longer than anyone can document. Members of the community may buy and sell the usufructs of portions of land among themselves, but all of it ultimately belongs to the community and may not be sold to outsiders. (At least it couldn't until Carlos Salinas changed the constitution in 1995 so that the land can be sold if its people vote to do so. Vergara did not ask to buy it.)

Therefore Pizota, unlike almost any other village of its size in Mexico, had some voice in whether or not its land would be leased. The entire community voted on the deal, even though most of the rent money goes to a few dueños (landlords) who hold title from Chacala to the land Vergara is leasing. The dueños agreed to turn over 10 percent of their rent to the community, Vergara sent his private jet to fly 15 Pizotans to Guadalajara for a Chivas game, and the project won big in a vote last November. Two days later, the contracts were signed. In February Omnilife held a party/sales meeting on the Pizota beach for 500 of its distributors, who arrived in two large ferries and spent a decorous afternoon eating rice and shrimp and consuming, to the astonishment of the locals, no alcohol at all. If that tradition continues, it will be an odd frontier town indeed.

Next week: Wiring up the jungle.

Shares