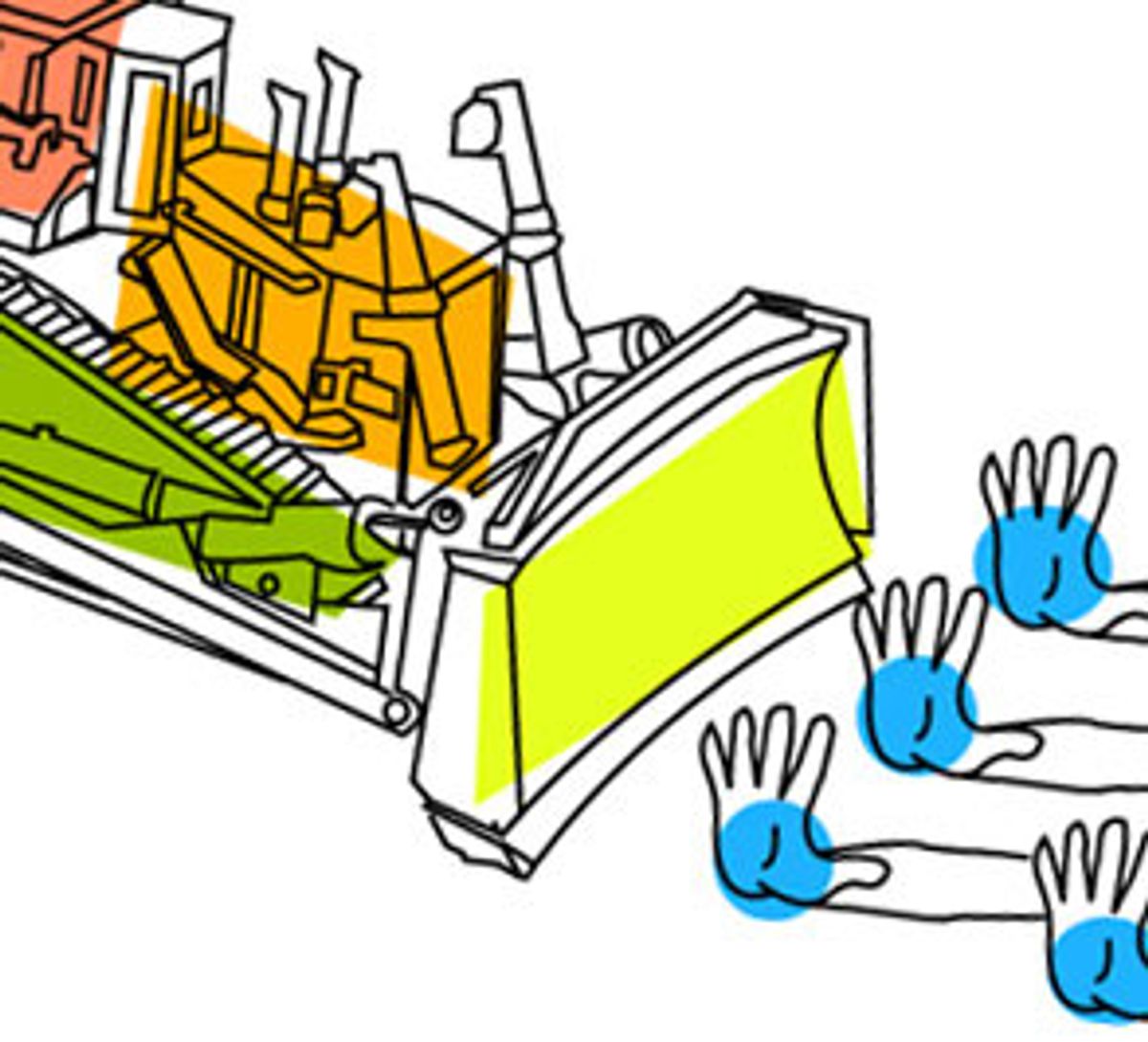

Late in the afternoon of March 16, 2003, Rachel Corrie, a 23-year-old American college student, put herself in the path of an Israeli army bulldozer that was moving to demolish the home of a Palestinian pharmacist who lived in the southern Gaza Strip town of Rafah. Either by accident, out of negligence, or on purpose, the Israeli bulldozer driver did not stop, and Corrie was crushed to death under the machine's giant blade.

The conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians brings us fresh horrors every day, but few events in the struggle seemed as senseless as what happened to Rachel Corrie. More than a year later, the simplest question about her death is still the most contentious: Who bears responsibility for what happened that day? The question is a test of political allegiance. Depending on your stance, you either blame the Israeli bulldozer operator -- for failing to stop for Corrie -- or blame Corrie herself for engaging in a protest tactic that the Israeli government has repeatedly called dangerous and irresponsible.

But now there's a new potential culprit. In recent months, some critics of Israel's actions in the Palestinian territories have been pointing at another key player in the drama of Corrie's death -- the Caterpillar D9 bulldozer, the unfathomably powerful machine that is the workhorse of the Israeli military, used to demolish hundreds of homes in the Palestinian territories during the past three years. Considering the role of Caterpillar equipment in Israel's occupation of Gaza and the West Bank, some critics of Israel are asking, shouldn't we assign some responsibility for Rachel Corrie's death to the American company that manufactured the bulldozer that killed her?

In April, Jewish Voice for Peace, a California grassroots group that advocates an end to Israel's occupation of Palestinian territories, and two other organizations sponsored a shareholder resolution asking Caterpillar to reexamine its business with Israel. At the company's annual meeting, stockholders representing only 4 percent of Caterpillar shares favored the resolution, but that percentage met a threshold that allows the groups to reintroduce their resolution next year.

Caterpillar's management responded coolly to the Israel resolution, saying, in a statement, that while the company felt "compassion for all those affected by political strife," it had "neither the legal right nor the means to police individual use" of the equipment it sells.

On one level, Caterpillar's position makes sense: Few sensible businesses are eager to shoulder the burden of monitoring how customers use the products they purchase. Israel, moreover, is using the bulldozers in line with the way they were intended to be used (to tear down structures) -- so if Caterpillar protests Israel's use of its bulldozers, wouldn't it have to do the same for other customers?

But Caterpillar's own "Code of Worldwide Business Conduct" envisions its products contributing to an "environment in which all people can work safely and live healthy, productive lives, now and in the future." Is that the case in Gaza? Advocates of the resolution say that shareholders should be wary that Caterpillar's business with Israel is turning the company into a military contractor, which is not necessarily the image you'd want associated with a company that thinks of itself as a builder of civilian dreams.

The issue thus raises a dilemma for Caterpillar: Is it better for the company's business and its image to stick with Israel, or to pull out of the country? More to the point, does Caterpillar bear any responsibility for how other people use its products? Many on Israel's side, including representatives of the Israeli government, do not think so. But when you ask Cheryl Brodersen, Rachel Corrie's aunt, whether she blames Caterpillar for her niece's death, she says, "Caterpillar knows how those machines are being used. They know the human rights violations are occurring. So do I hold them responsible? They bear some responsibility."

Caterpillar's D9 bulldozer, which weighs about 60 tons and stands about 13 feet tall, is engineered, Caterpillar's Web site says, "for demanding work." The bulldozer is equipped, like a tank, with a pair of all-terrain rubber tracks in place of wheels, and the models used in Israel are often retrofitted by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) with armor plating and other accoutrements of a modern military, including machine guns and even grenade launchers.

The D9 and its larger cousin, the D10, are the Israeli military's construction weapon of choice in the country's conflict with the Palestinians, often accompanying other, more traditional, military equipment on raids into Gaza and the West Bank.

Israel routinely uses Caterpillar equipment to demolish the homes of suicide bombers and wanted suspects in terrorist attacks. According to the Israeli human rights organization B'Tselem, the IDF has demolished more than 550 Palestinian homes since October of 2001 as part of this campaign. Daniel McQueen, a research analyst at the Investor Responsibility Research Center, an independent firm that offers guidance on shareholder resolutions put forward at corporations, says the Cat D9 is so central to the military's work in the Palestinian territories that Israeli troops even have an affectionate nickname for the machine -- "Duby," the Hebrew word for bear.

Because it uses Caterpillar bulldozers against the homes of suicide bombers, Israel maintains that Caterpillar equipment is crucial to its fight against terrorism. But the groups that call for Caterpillar to curb its sales of bulldozers to the IDF complain that Israel does not always use great care in targeting Palestinian homes for destruction. For instance, they point to the raid of the Jenin refugee camp in April 2002, which Israel carried out in response to a Palestinian suicide bombing in the city of Netanya that killed 29 Israelis. In that incursion, the IDF used Caterpillar equipment to completely or partially destroy more than 300 Palestinian homes. In its report on the Jenin raid, which killed 52 Palestinians and 23 Israeli soldiers, Human Rights Watch criticized the IDF's use of bulldozers that were "sent in to clear paths through Jenin camp's narrow, winding alleys." This tactic, Human Rights Watch said, left civilians little time to flee.

"In some cases civilians were not adequately warned of the impending destruction, and in one case a handicapped person died as his house was bulldozed above him and as relatives pleaded with the soldiers to stop," the organization reported. "The damage caused by the bulldozers caused permanent damage to many buildings and rendered others uninhabitable or unsafe. Water and sewage mains were disrupted, as well as much of the other infrastructure." Groups calling for Caterpillar's withdrawal from Israel also point out that Israel does not only destroy homes as a response to terrorism; it has, in fact, demolished many more Palestinian homes as part of its settlement-building policy in the West Bank, B'Tselem notes. The Israeli government is also using Caterpillar bulldozers in the construction of the barrier Israel is building along its border with the West Bank; although the Israeli public is widely supportive of the barrier as a necessary measure to prevent terrorist attacks, Palestinians have bitterly criticized the structure for cutting into their territory.

Proponents of the Caterpillar resolution draw a direct parallel between their action and the effort, during the 1970s and '80s, to call on American corporations, banks and universities to stop doing business with the apartheid government of South Africa. In that campaign, countless protests by college students, religious leaders, and ordinary customers persuaded many American firms to cut or loosen ties with South Africa. The consequent economic hardship this caused to the South African regime has been credited with leading, eventually, to apartheid's end.

For advocates of what's called socially responsible investing, the campaign to divest from South Africa stands as the primary example of how ethically based financial decisions can bring about positive changes in politics. The conflict in the Middle East, though, is immeasurably more complex than the one in South Africa, because, at least in the United States, there's no clear consensus over which side in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has a legitimate claim to the moral high ground. Israel regards any comparison between its actions and those of the apartheid South African government as odious.

"It is yet another example of trying to equate what goes on with our area with what clearly was an evil system and an evil regime," says David Roet, the deputy consul general of Israel to the Midwest, where Caterpillar is based. The main difference between what goes on in the Middle East and what went on in South Africa is obvious, Roet says -- terrorism. "It is not the Israelis that need to be pushed for change. All that needs to be done is to stop terrorism -- there will be no need for a boycott if terrorism is stopped. We don't need any encouragement to realize that in order to settle this we must make necessary concessions." But Israel must act against terrorism, Roet says, and for that it needs Caterpillar bulldozers.

A company weighing its options on whether to do business with South Africa during the 1980s had to make a relatively simple choice -- between the short-term monetary benefits of working with the apartheid government and the perhaps longer-term costs, even if only to a firm's image, of staying in a country whose policies were almost universally reviled. But a company weighing whether to work with Israel faces a more complex calculus. The decision to pull out of Israel might bring not just a financial cost, but also a cost to the company's image: If Caterpillar chose, tomorrow, to discontinue sales of its bulldozers to the IDF, the outcry against the firm -- for being "soft" on terrorism, for being friendly to Israel's enemies -- might be louder than the current protests.

Liat Weingart, the director of operations and programs for Jewish Voice for Peace and one of the architects of the shareholder resolution at Caterpillar, says that she recognizes the crucial political and moral differences between South Africa and Israel. Weingart, who was born in Israel and for whom the conflict has been "the backdrop of my life," sees that "the emotions around this issue and people's reactions to it, and the narrative in this country, makes it more complicated ground to navigate."

That's why, she says, Jewish Voice for Peace isn't calling for a general divestment from Israel, and it's not technically even asking Caterpillar to stop doing business with the country. All that Jewish Voice for Peace and its sister organizations want Caterpillar to do, Weingart says, is to thoroughly and openly review the company's policy of selling equipment to the IDF. Caterpillar prides itself on being a firm committed to social responsibility, Weingart notes. So shouldn't the company at least examine whether sales to Israel are in line with its mission of responsibility? And, of probably even more importance to shareholders, shouldn't the firm do a thorough review of whether Israel's use of Caterpillar bulldozers -- in Jenin, in the building of the West Bank barrier, in Rachel Corrie's death -- might someday cause serious harm to the company's image and, therefore, its bottom line?

When Jewish Voice for Peace initially conceived the idea of putting forward a resolution to Caterpillar's shareholders, the group owned no shares in the firm, so they sought help from the Mercy Investment Program, a pooled investment fund set up for the Sisters of Mercy, a worldwide group of Roman Catholic nuns who commit their lives to helping the poor. The Mercy Investment Program, which is a veteran of the socially responsible investing movement, owned enough Caterpillar shares to file a resolution; it co-filed with the Sisters of Loretto, another community of Roman Catholic nuns. The resolution, says Valerie Heinonen, an Ursuline sister who heads the Mercy Investment Program's responsible investing efforts, was designed to illustrate to Caterpillar shareholders the economic -- rather than the possible moral or ethical -- difficulties that Cat might face in working with Israel.

"We are looking at these kinds of issues from the viewpoint of the investments that we have in these companies," Heinonen says. "Basically what we're talking about here is pension funds. So we're not telling the management of the company to go out of business. We're hoping to keep them in business. But we want to show that there's potential liability. Nobody seems to care that the Palestinians are dying -- but once, for example, you have things like the incident of Rachel Corrie, once you start having people from outside that immediate area dying as well, that could lead to a P.R. disaster, and the cumulative value of Caterpillar could fall."

Specifically, the resolution the groups put forward asked the company's board to issue a report that examined whether the sales of Caterpillar equipment to the IDF are in line with the company's "Code of Worldwide Business Conduct" (published on the Web in PDF format). "We are concerned by the actual and potential damage to Caterpillar's international sales and worldwide reputation because of the widely-publicized use of Caterpillar equipment ... to destroy Palestinian homes, infrastructure and agricultural resources," the resolution states. "We are interested in determining if the evidently small amount of revenue derived from these sales outweighs the economic and public relations costs, especially in the United States, Europe and Arab countries, and whether Caterpillar's directors can reconcile acquiescence in the IDF's use of this equipment for these purposes with Caterpillar's Code of Worldwide Business Conduct."

In its code of conduct manual, Caterpillar, like many other big corporations concerned about its image in the world, has promised that its business practices will adhere to a set of saccharine-sounding, vaguely progressive principles -- for instance, the maintenance of "a global environment in which all people can work safely and live healthy, productive lives, now and in the future," or the belief in "working and living according to strong ethical values."

It's not clear that Caterpillar's sales to Israel violate this code, but it is at least possible that they might, proponents of the shareholder resolution contend. If Caterpillar truly values this code -- which it calls the most important document the firm has ever published -- shouldn't managers at least care to investigate whether sales to Israel comport with the code?

Caterpillar did not return several requests for comment on the shareholder resolution. The company has always maintained, however, that since there are millions of Caterpillar products working in every region in the world, it cannot possibly monitor how the equipment is being used on a daily basis. But as Daniel McQueen of the Investor Responsibility Research Center points out, this response seems to put the lie to all of the company's sunny pledges in its code of conduct manual. If Caterpillar really has no way to stop its customers from using the bulldozers however they please, how can it pledge, for instance, to be a champion of sound environmental policies, as it does in its code of conduct? Would it sell bulldozers to a company or a government that was bent on using the equipment for doing something environmentally disastrous? Does it do so already?

On April 14, at Caterpillar's shareholder meeting in Chicago, about a half dozen supporters of the resolution made their case to Caterpillar stockholders. The shareholders were, for the most part, unresponsive to the activists' claims. "They responded by saying, 'Thank you for your polite speeches,'" says Weingart. Brodersen, Rachel Corrie's aunt, remembers that when she addressed the crowd, "one shareholder yawned through the whole thing. I would say they were all -- they were pretty much older gentlemen, almost if not totally all white faces. They were all in suits. And so I think -- if I were to project my feelings, I would say we were humored."

Weingart and Brodersen were pleased, though, that at least one shareholder seemed to get what they were saying. According to press reports, this stockholder, James Stahr, told the assembled crowd that while he was voting against the resolution, he felt that its proponents had a point. "Caterpillar has got to be awfully careful about its image," he said. "Just to say we're concerned and compassionate is not enough. They have to be serious about how their products are used."

Weingart says she's pleased that the resolution got 4 percent of the vote; considering the novelty of such a resolution, that number is not bad, she says, especially since the group will have future opportunities to file its request. Heinonen adds that even if the resolution is never passed, it still might be called a success by other measures. "I think the major value to a shareholder resolution is that the issues are brought to management and the board of directors directly and to the shareholders as well. If we're a part of an environmental movement or a disarmament movement, we don't often have the chance to address these kinds of people. They're not the kinds of people we usually talk to, and sometimes it can be a very large audience."

Caterpillar's critics hope that the resolution, despite garnering only 4 percent of the vote, will help to break through the disengagement that many Americans have with events in the Middle East. They believe that outrage should be an easy thing for most Americans to muster.

Why should Americans ask Caterpillar to stop selling bulldozers to Israel? "I think that if I know that someone is going to use something that I produced to harm another human being, and I don't do something to stop it, then some guilt lies with me," Brodersen says. "For instance if I become angry at somebody and I pick up a knife and go running out the door with that knife and tell everybody that I'm going to hurt someone with that knife and my family doesn't try to stop me, then they would bear some of the blame. That's why I was there at Caterpillar that day. I don't want to carry that blame. I don't think we have the full picture. I think that those board members would not have felt comfortable if they had seen the photo that I carry with me of Rachel just after the bulldozer pulled the blade over her."

Brodersen is right; it's hard not to feel uncomfortable looking at that picture of Corrie. But a lot of what goes on in the Middle East these days makes one uncomfortable, and heartbreaking pictures rarely offer a good guide for what we should do. Isn't it just as understandable to look at pictures of Israeli victims of suicide bombs and conclude, as the consul David Roet does, that Caterpillar bulldozers are aiding the peace process by helping in the construction of the barrier wall that he believes will stop terrorism?

Shares