Like many of you, I am hooked on the aesthetics and pageantry of “Serial.” I’m maybe not as bad as the people buying “Shrimp Sale at the Crab Crib” T-shirts, but I’m a communicant at the Church of Sarah where the services always begin with the woman offering the counterintuitive pronunciation of “chimp” and where the only hymn is that Nick Thorburn piano theme.

I’m fascinated by Sarah Koenig as the Lt. Columbo of 2014 – a disarming, halting, fumbling, backtracking, oversharing sleuth who gets people to talk unguardedly, maybe because she herself seems a little blurry around the borders. And yes, I’ve seen the parody. And the rap. I’ve listened to the podcasts about the podcast. As a McLuhanist, I have a lot of ideas about what’s going on here at the level of media theory.

But all that has to wait, now that the final episode dropped and made a fairly grim point about law and order in the United States: with the exception of cops exercising undue force on civilian populations, it’s pretty easy to get locked up in this country.

We operate under a justice system that – theoretically -- places the burden of proof on the prosecution and requires proof beyond reasonable doubt. It’s a great idea, but the system doesn’t work very well. If it did, we wouldn’t have many people in prison, but, of course we have a lot. One out of 100 of us are incarcerated. Something’s wrong, right? If we have the strongest presumption of innocence and the highest standard of proof, why are we “the world’s largest jailer,” as the ACLU puts it. We have 5 percent of the world’s population and 25 percent of its prison population.

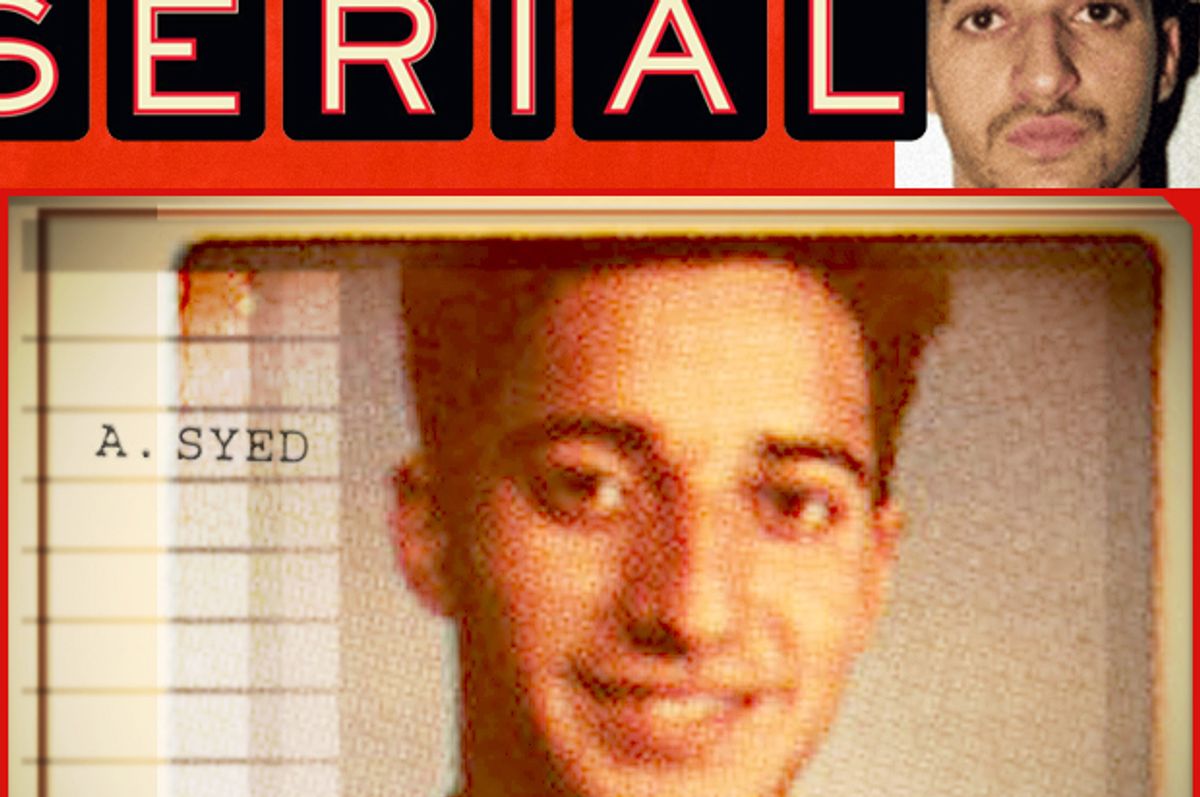

Adnan Syed, now a household name for millions of “Serial” podcast listeners, is not the perfect poster boy for that, but he’ll do. Arrested in 1999 for the murder of his ex-girlfriend Hae Min Lee, he’s serving a life sentence in a maximum security prison. It’s quite possible that he did it, but, as the curtain rang down this week on “Serial,” it was also possible to peek through the haze and see, once again, Syed’s case for what it really is: a flimsy, ramshackle prosecution built around one weak and unpersuasive witness. It would have been enough to get a lot of defendants to take a plea deal, but it never should have worked in court.

We also saw prosecutorial overreach, some of which was winked at by the court. We learned that prosecutor Kevin Urick arranged free legal representation for “Jay,” his star witness and, by his own testimony, an accomplice after the fact. And in the final episode, “Don,” the boyfriend who replaced Syed, said that Urick “yelled” at him after his testimony in each of Syed’s trials because Don failed to make the defendant sound creepy enough.

And there can be little doubt that Syed received ineffective assistance from his defense lawyer, a woman who was circling the drain in a whirlpool of health and personal crises and whose failure to run down very basic types of information seems to have provided the initial fuel for the “Serial” rocket.

It would be a terrible thing if Syed killed Hae Min Lee and got away with it, but one of the formulations – often difficult to swallow – underscoring our notions of justice is Blackstone’s: that it is better for ten guilty persons to escape than for one innocent to suffer. That’s what we say, but it’s not how we roll – not in Maryland and certainly not in Gitmo or any of the torture sites. In fact, Dick Cheney recently said he’s cool with jailing innocent people if that’s what it takes to net the actual terrorists.

Meanwhile, Syed did the worst possible thing you can do once you’re in the jaws of our system: he steadfastly insisted on his own innocence. In American justice, that’s treated more like saucy backtalk than like an inalienable right. He didn’t take a plea. He pushed for a trial. In prison, his continued unwillingness to change his story and exhibit remorse makes parole nearly impossible.

Now that the “Serial” party is over, maybe we can have an honest discussion about criminal justice, unless you think Koenig somehow found the only guy in prison who got a raw and cosmically capricious deal. At minimum, we should be talking about “second look” legislation for young offenders. One of our many oddities in the U.S. is the way we drop the full load of criminal penalties on young people whose brains and personalities are not fully formed. Syed was 17. There’s no coherence, state by state, on this question. Connecticut, where I live, had a second look bill in the pipeline last session and failed to pass it due largely to legislative incompetence. A little more noise from the citizenry would have helped.

So think about that. Maybe get involved. Then – and only then – you can think about getting one of the T-shirts. Personally, I think this one – which plays with the podcast logo – is more fly.

Shares