"Libertarianism," like its ideological cousin neoliberalism, is one of those words that people in the political world use a lot without establishing whether everyone agrees on its meaning. This doesn't really matter in the vast majority of cases (because nothing that happens during a fight in a comment thread or on Twitter matters). But as support for libertarian-backed causes like marriage equality, opposition to the war on drugs, and resistance against the rise of mass incarceration become ever-greater parts of U.S. politics, the definition of libertarianism will matter more, too — for the sake of apportioning credit and blame, if nothing else.

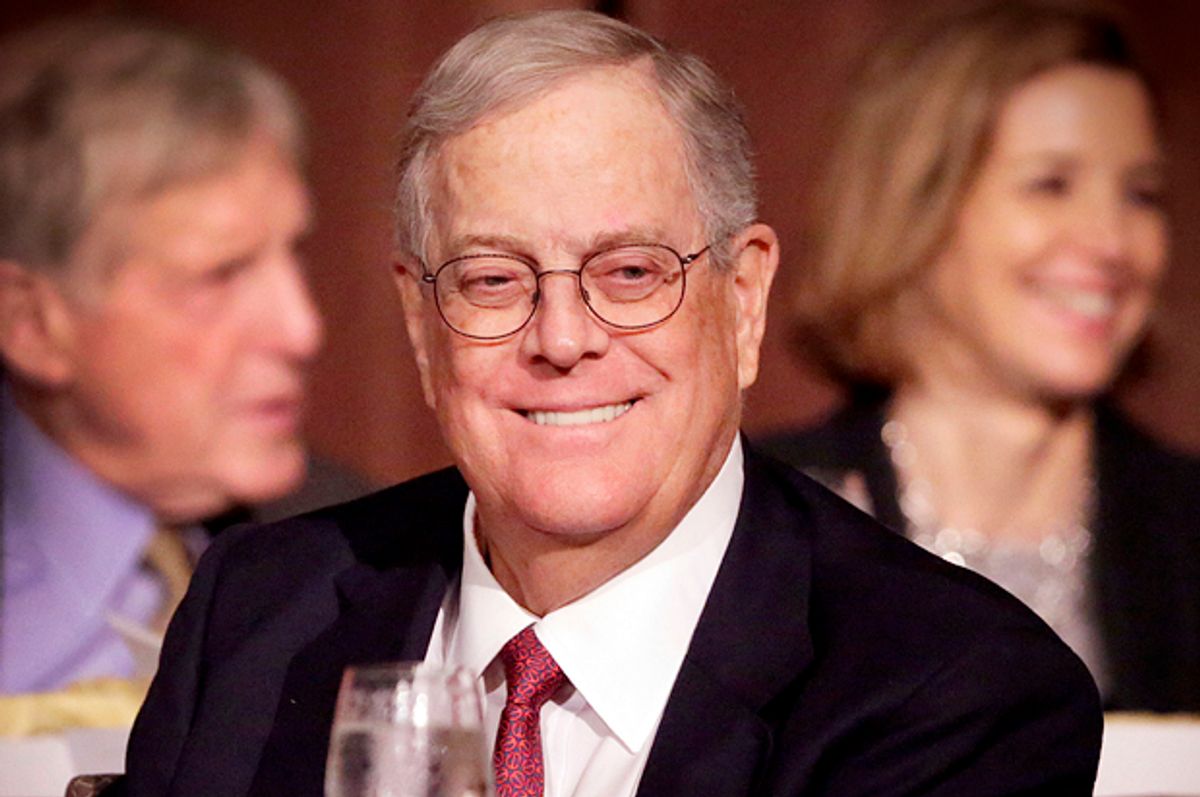

In the interest of nailing down a famously elusive and controversial term, then, Salon recently spoke over the phone with David Boaz, longtime member of the influential and Koch-founded Cato Institute think tank and author of "Libertarianism: A Primer," which was just updated and rereleased as "The Libertarian Mind: A Manifesto for Freedom." Our discussion touched on the big issues mentioned above, as well as Boaz's thoughts on what liberals and conservatives misunderstand about libertarianism, and why he thinks his favored political philosophy's future is so bright. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

If you had to pick one defining or differentiating characteristic of the libertarian mind, what would it be?

The first line of the book says that libertarianism is the philosophy of freedom, so what distinguishes libertarians is their commitment to freedom. That can manifest itself in lots of different issues, from marijuana and gay marriage to smaller government and lower taxes, but the fundamental idea of freedom as the proper political condition for society is the thing that unites libertarians.

Wouldn't most Americans say they care deeply about freedom, though? So is it the definition of freedom that distinguishes libertarianism from liberalism and conservatism? Or is it where freedom ends up in the hierarchy of values?

In America, virtually everybody comes out of the classical liberal tradition. The classical liberal tradition of John Locke, Adam Smith, Thomas Jefferson, and John Stuart Mill stresses freedom under law and limited government and most Americans share that. The difference with libertarians is that we do make freedom our political priority. Freedom is not necessarily any person’s primary value. Your primary value may be courage or friendship or love or compassion or the arts; but freedom is the primary political value for libertarians.

I do think that is a difference between libertarians and liberals or conservatives who value freedom but also value other things. Modern American liberals would say, I believe, that they value equality along with freedom. Libertarians would tend to respond, well, in the real world you get more equality when you have freedom and free markets, though libertarians certainly believe in equal rights and equal freedom. Some conservatives value doing God’s will or maintaining social order or maintaining tradition along with freedom.

In that sense, I do think libertarians put freedom at the center of their political philosophy in a way that many liberals and conservatives do not.

If you had to pick one thing about libertarianism that liberals misunderstand the most, what would it be?

I think there is first a misunderstanding that libertarians are conservatives — and I think that’s wrong. Libertarians are classical liberals. We trace our heritage back to, not the aristocracy or established church, but to the liberal thinkers and activists who challenged those institutions.

Secondarily, I think liberals overlook how many issues libertarians and liberals share even today: religious freedom, freedom of speech, First Amendment issues, concerns about surveillance, opposition to endless war, marriage equality, opposition to the drug war, etc. There are a whole lot of such issues and my sense is that a lot of American liberals don’t see those very specific connections between libertarian and liberal interests.

Well, I can tell you, as a lefty, that the counter to that claim you often hear is that libertarians don't pay many of those issues more than lip service, and that when push comes to shove, it's economic policy that they really care about. What do you say in response to that charge?

Well, there’s a lot of different libertarians. We’re not a democratic-centralist organization, so we’re allowed to have our own opinions.

Certainly, there are some libertarians who prioritize economic issues, but there are libertarians who have devoted their lives to fighting the drug war; there are libertarians who are very actively against crony capitalism these days. I think libertarians have been the most forthright opponents of war in Washington for a generation at least; I remember being fairly lonely when the Cato Institute opposed the first Gulf War. So it may be a fair criticism of some libertarians, but I don’t think it’s fair criticism of the libertarian movement overall.

I would add that libertarians do believe that you can’t have peace and civil liberties and freedom in a society that isn’t fundamentally based on private property and market exchange. Obviously, that leaves room for a range of economic arrangements, from true laissez-faire capitalism to Sweden; but we do understand that when government is too dominant, when private property and markets are intruded upon too much, then you will lose personal and political freedom.

And how about if we took the same question but applied it to conservatives?

From conservatives, I think there’s a misconception that libertarians don’t care about morality. Plenty of libertarians care about morality. But as individuals, they tend not to want the government to enforce anybody’s personal morality beyond the basic [things] that are necessary for us to live together in society — rules like don’t hit other people and don’t take their stuff.

When you talk about whether individuals should use alcohol or marijuana or whether individuals should be heterosexual or homosexual or how individuals should worship God, libertarians say those things should be left in the realm of civil society and persuasion. And obviously conservatives disagree. They think the government should be involved in those kinds of questions.

Sometimes, the way libertarian intellectuals view libertarianism is different from the way libertarian views are reflected by public polling data. If we want to understand what libertarianism really is, why should we look more to the writings of its philosophers rather than the sentiments of the rank-and-file?

Well, I’ve written a book based on the ideas of a political philosophy called libertarianism, but people who call themselves libertarians may or may not believe these particular things. The libertarians I know believe these things with the proviso that no two of us agree on everything, but the general principles of liberty, limited government, individual rights, peace, personal freedom, economic freedom — that’s the core of the libertarian idea.

What people who call themselves liberal, conservative, or libertarian may actually believe, I don’t think tells you what the core philosophy actually is. I’m not sure what polls say about what libertarians believe because actually very few Americans call themselves libertarians. In work that I’ve done, we find that a very large percentage of Americans, 20-25 percent, hold views that I would call broadly libertarian. But most of them would not call themselves libertarian.

There’s no question that in America there are plenty of people who say they believe in liberty and they don’t like government health insurance and they don’t like high taxes and they hold views that I think are un-libertarian. It’s also true that there are people who say the United States should unnecessarily meddle in the affairs of other countries and should not arrest people for peaceful activities like smoking marijuana and who also hold views that I would consider un-libertarian.

It’s a big wide wonderful world and people hold all sorts of combinations of views. I think that libertarian views are probably more coherent than either modern conservative or modern liberal views, and maybe that’s just because libertarian views tend to be defined by intellectuals [rather] than by politicians.

You’ve written before that the future is bright for libertarianism in the U.S. In terms of policy outcomes, where do you think we'll see some changes in a libertarian direction in the near- or medium-term future?

It’s probably easiest to see policy changes in the area of marriage equality and marijuana liberalization; economics is going to be a continuing fight.

One of the things that happens in America is that Americans have a very gut-level libertarian sentiment: they believe in freedom, they distrust government, they don’t like power. When government pushes to get bigger, as it clearly did in 2008 and 2009, there’s a push back on that. I think the rise of the Tea Party was clearly a manifestation of this on-going American libertarian spirit. What essentially happened was that for two years the Tea Party libertarian spirit failed to stop very much that Congress was doing. But since 2010, there has not been much further expansion of government, so I think that’s a libertarian victory. I also think that the failure to pass much gun control is a libertarian victory.

But I would also point overseas. Where am I the most optimistic? I am optimistic that around the world more and more people are moving into a world of property rights, markets, globalization, human rights, women’s rights, access to information and opportunity. Now that’s obviously not true everywhere; there are, at any given moment, unfortunate setbacks in Venezuela and Russia and some of Eastern Europe. But I do think the largest historical trend of our time is the move in a broadly libertarian direction, and therefore toward a higher standard of living for billions of people around the world.

Are you thinking of the growing middle class in China and India when you say this?

Absolutely. The change in economic conditions in China and India — right there you got one-third of the world. But also there have been some advances in the direction of human rights in Africa as well. So in a great deal of the world, you’ve seen a huge reduction in poverty and absolute poverty, and a rising middle class in many of these countries.

Does the increasing focus on inequality make you nervous in the other direction, though? Do you think libertarians should worry that once this debate gets going, the question over redistribution becomes a matter of "if" rather than "when"?

It could, and that is something that should make libertarians nervous. However, classical liberals, from the beginning, were fighting inequality. They were fighting cronyism and aristocracy and the society of status. They advocated a society of merit instead of a society of status. Libertarians need to deal with the current concern over inequality by highlighting the various ways in which government remains the friend of those with political connections, those with political power, so we should be working, and we are working, to get rid of monopolies and companies with protection against competition.

I think that you see this in the case of Uber, [which is] rising to challenge the taxi cartel in every city; there’s more opposition to stadium subsidies, which are just government giveaways to billionaires; tariffs and other restrictions on free-trade protecting incumbent businesses against consumers. In all of those areas, government is helping to build inequality and libertarians should be and are talking about those issues.

Where we’re going to disagree with modern liberals ... is on the idea that the way to deal with inequality is to limit investment, limit the returns on investment and redistribute money through the government. We’d rather focus on the ways the government helps redistribute money upward.

What about the idea that libertarianism focuses so much on government coercion that it doesn't see where there's tyranny in the private sphere, too? How do you respond to that argument?

My main response is that we should be clear on what power is. Power is the ability to force people to do things they don’t want to do. I don’t think corporations have that kind of power. Corporations can offer a Coca-Cola or Facebook ... but they can’t force me to use any of those things.

Government, on the other hand, can arrest me for running a lemonade stand, for carrying a pocket knife in my pocket ... for demonstrating against the president, for smoking marijuana; all of those kinds of things are real power. And so, absolutely, libertarians are fundamentally concerned with the problem of controlling [government] power.

Shares