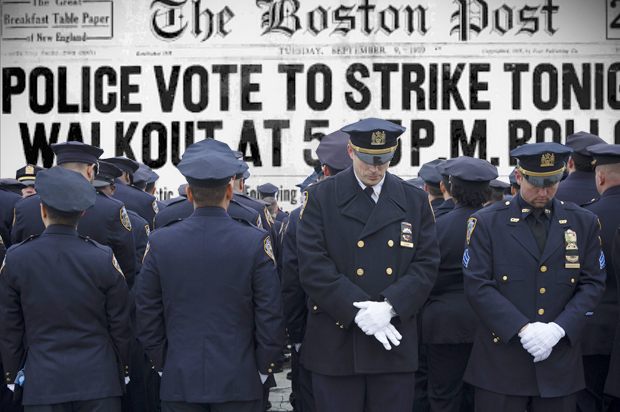

Nearly a century separates the historic Boston police strike of 1919 from the December-January work slowdown of the New York City Police Department (NYPD), but especially for the NYPD’s conservative supporters, the lessons from the Boston strike on what police owe the city they work for remain relevant.

The NYPD’s supporters believe the police are right to be angry with New York mayor Bill de Blasio because he has questioned how the NYPD has used stop-and-frisk tactics in dealing with the city’s minority community. They particularly resent de Blasio saying publicly that he has told Dante, his mixed-race, 16-year-old son, who sports an afro, to take special care in any police encounter.

The problem for the NYPD’s conservative supporters is that championing the NYPD slowdown conflicts with their longtime support of the principle that grew out of the Boston police strike — namely, government employees responsible for public safety never have a right to strike or play fast and loose with the law.

The Boston police strike began in a year of widespread labor unrest in America. Seattle had undergone a general strike earlier in the year, and with World War I at an end, the underpaid and overworked Boston police let it be known that they wanted to join Samuel Gompers’ American Federation of Labor (AFL). When 19 of them took the lead in joining the union, they were immediately fired; in sympathy a thousand police then walked off the job.

The reaction of city and state authorities was to call in state troops, and in short order the strike was put down. Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell even told his students that if they volunteered for police duty, the university would schedule makeup exams for any test they missed. For Calvin Coolidge, then the governor of Massachusetts, it was not, however, enough to thwart the striking Boston police. He also insisted that they could not get their old jobs back, and in a ringing telegram that won him national attention, he declared, “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time.”

As the historian Amity Shlaes has pointed out in her recent, admiring biography of Coolidge, the telegram and tough stance made Coolidge a national figure. He won a permanent place for himself in conservative circles. Ronald Reagan admired Coolidge so much that as president he replaced the portrait of Harry Truman that hung in the Oval Office with that of Coolidge. More important, he followed Coolidge’s Boston-police example to the letter when, in 1981, striking air traffic controllers refused his orders to go back to work. Reagan fired all the workers who disobeyed his order, even though the firings made the nation’s airports less safe for many years. “You can’t sit and negotiate with a union that’s in violation of the law,” Reagan declared. “Government . . . has to provide without interruption the services which are government’s reason for being.”

The Boston police lost public sympathy when rioting broke out during their short strike. The Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) was hurt by the impact of its strike on airplane passengers. By contrast, the NYPD, which skirted the law during a slowdown that now appears to be winding to a halt, has not quite suffered a comparable public relations setback — yet.

The NYPD is not, however, home free. In the incident that became the immediate cause for the protests against the NYPD in December, the police can be seen on a cellphone video putting what turned out to be a fatal chokehold an unarmed Staten Island African-American, Eric Garner, whom they allegedly caught selling “loosies,” untaxed cigarettes, on the street.

Whether the violent arrest was an overreaction has been debated, but what followed the violence is a different story. In the video, Garner, who suffered from asthma, can be seen repeatedly complaining, “I can’t breathe,” and later, as he lies helpless, and then unconscious, neither the police nor emergency service workers make any effort to apply CPR. Whether Garner lived or died appears to have been a matter of indifference to them.

The New York Post, which along with the Daily News, the city’s other major tabloid, has championed the police, has already warned the NYPD about the dangers of a slowdown. “This is a highly dangerous game,” the Post cautioned in a recent editorial. “By not doing their jobs, cops risk losing the support of the vast majority of New Yorkers.” Whether the Post speaks for the NYPD’s conservative backers is an open question. The latter may, after all, think there are times when exceptions should be made to the Coolidge-Reagan hard line on the law and government workers.

Meanwhile, a new poll from Quinnipiac University brings a clear message: “Voters say 57 – 34 percent that officers should be disciplined if they deliberately are making fewer arrests or writing fewer tickets. Black, white and Hispanic voters all agree.”