Let me tell you a story. It’s a story inspired by the tragic events of Wednesday morning, of yet another shooting in which two innocent people were killed followed by the gunman shooting himself, all grotesquely documented on social media.

But it’s not a story about this morning. It’s a story about the 19th century.

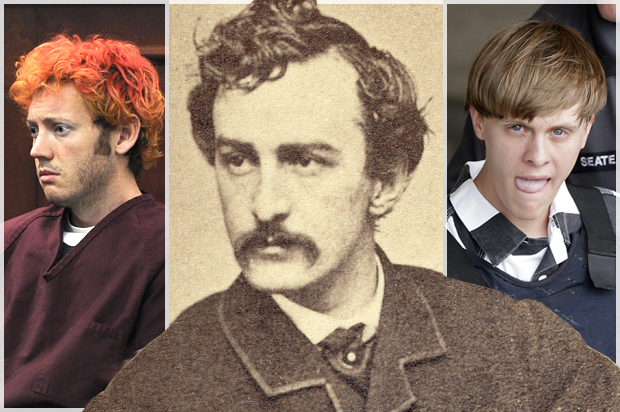

We all know the story about the first presidential assassination, John Wilkes Booth assassinating Abraham Lincoln in 1865 in order to avenge the South. Much is made of Booth as the first of the neo-Confederate reactionaries that would form the Ku Klux Klan and similar organizations, the legacy of insurgent white supremacy he left behind.

But what’s less emphasized is that Booth was a troll. He did what he did not because he had any concrete plan for re-igniting the Civil War but because he wanted to plunge the Union into chaos and fear. He was an accomplished stage actor, the equivalent of a movie star, the younger brother of Edwin Booth, called by some the most distinguished Shakespearean actor in history. He arranged Lincoln’s murder to be as theatrical as possible, to occur immediately after the act break in the play so that he could heroically leap onto the stage shouting words of defiance, “Sic semper tyrannis” and “The South is avenged!”

He did it, above all, for the attention.

The only difference between our Internet term “troll” and the scary real-world term “terrorist” is the scale of the attention-seeker’s ambitions.

Which is why I want to talk about the second presidential assassination in history, the assassination of James Garfield by Charles Guiteau in 1881. I can think of no clearer demonstration of Karl Marx’s aphorism that history repeats “first as tragedy, then as farce.”

Tour guides and history textbooks tend to gloss over the kind of man Charles Guiteau was by calling him a “disgruntled office seeker,” just like the sanitizing use of the term “disgruntled” about this morning’s murderer, as though murderous violence were a normal response to workplace disgruntlement.

Charles Guiteau was never a serious “office seeker.” Whether or not he had a diagnosable mental illness — something people argued about then and still argue about now — he was a screwed-up human being whose lifelong screwups stemmed from a constant feeling of entitlement to others’ attention and unwillingness to do anything worthwhile to earn it.

John Wilkes Booth was a talented actor whose talent wasn’t enough to grant him the notoriety he craved to push himself out of his famous brother and father’s shadows. Guiteau was a man of no discernible talents who dropped out of school to join a utopian cult, only to be kicked out of the cult and end up trying to found his own competing cult and sue the original cult for ownership of their ideas. He then got a law degree and turned to spamming Republican political candidates with endless copies of pamphlets he wrote that he believed would be essential to a Republican political victory.

When the Republican Party refused to reward him with official recognition or a civil service position (he wanted to be Ambassador to France), he went out and bought a gun and shot the president.

He went on to be happy as a clam in federal custody, testifying frequently and ramblingly on his own behalf, giving interviews to everyone who asked, publishing an autobiography, planning a lecture tour and, when he was finally sentenced to execution, writing a poem to recite on the way to the gallows.

Unlike Booth, Guiteau had no clear political cause to hitch himself to, no noble “movement” he was defending — he tried to claim that he shot Garfield, a “Half-Breed,” on behalf of the “Stalwarts” in the Republican Party, but even a cursory look at his life shows him to be a total outsider to the factional intraparty politics he was invoking.

The only side Guiteau was on was his own side, and the only cause he had was getting people to pay attention to him and say his name. And it worked. People were buying up fragments of the rope used to hang him, and they had to put his corpse in a museum just so people wouldn’t dig it up for souvenirs.

It all sounds very modern, doesn’t it? The only things that aren’t modern about it are that Guiteau had to make paper copies of his political rants because there was no freerepublic.com or townhall.com to post to, and the auction of the gallows rope had to be done in person because there was no eBay.

But all the pieces were in place for the “celebrity killer” — the existence of a fast-moving national news media powered by the telegraph and its associated wire services, the attendant transformation of trials into public spectacle as witnessed at the trial of Booth’s conspirators, the script already written into people’s minds of ritually denouncing the crazy man while obsessing over his freakish eccentricities.

Charles Guiteau had, by watching John Wilkes Booth’s example, come up with a formula for fame. It’s one that wouldn’t appeal to most people, who prefer living freely if obscurely to notoriety from inside a jail cell or beyond the grave.

But there’s always people who seem to want to be important, to be significant, to be paid attention to more than they want anything else. They’re willing to give up everything for it, to kill others and to kill themselves, as long as people say their name. And the world keeps obliging them.

You see this pattern over and over again with history’s other famous killers. The sheer theatricality of the planned atrocity. Lee Harvey Oswald passing out pamphlets for his supposed Communist Party cell (founded by himself, with himself as the only member), being ignored by both the actual Communists and the US government until he took matters into his own hands. John Hinckley, Jr. hoping to get into the newspapers so his Hollywood crush Jodie Foster would notice him — patterning his behavior on Robert De Niro’s Travis Bickle from “Taxi Driver.”

Timothy McVeigh comparing his bombing of the Oklahoma City Federal Building to the Rebels blowing up the Death Star in Star Wars, and having William Ernest Henley’s “Invictus” read as his final statement. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold’s career as dedicated early-Internet edgelord trolls who cited McVeigh as their inspiration for their own blaze of glory. Seung-Hui Cho making a rambly incoherent video manifesto posing as Choi Min-Sik from “Oldboy” and piecing together bits and pieces of dialogue from dozens of cinematic “bad-boy” antiheroes.

People piggyback on all kinds of causes. Supporting extremist Islam. Opposing extremist Islam (and Sikhs who happen to look like Muslims to the shooter). Opposing feminists. Opposing socialists. Opposing local zoning regulations. Doing a bad impression of a Hollywood/comic-book version of anarchism. Even in 2015, we still have folks like Dylann Roof fighting for the same cause as John Wilkes Booth, the Lost Cause of the South (and of Rhodesia and old South Africa) and legal white supremacy.

And then you have Bryce Williams/Vester Lee Flanagan, who sent a 23-page fax to ABC News piggybacking on Dylann Roof’s notoriety — just as Dylann Roof piggybacked on Trayvon Martin by mentioning him in his own manifesto — by calling his shooting payback for Roof’s shooting. He then, somewhat confusingly, invokes as mentors Seung-Hui Cho, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, even though Eric Harris is on record as being an admirer of Nazism who planned the Columbine shooting to coincide with Hitler’s birthday and taunted his victims with racial slurs.

The issue of high-profile mass murder is complex. It’s almost always men who do it. It’s usually white men — and, disproportionately, Asian men — and it happens far more often in America than anywhere else in the developed world. The killers are disproportionately people of privilege, people from the suburbs, people who are attending college or have college degrees — in some cases, like the case of BMW-driving Hollywood-studio-party-attendee Elliot Rodger, they come from great wealth.

Part of the reason the American middle class breeds so many murderers is how easy it is for a member of the American middle class to buy a gun. (Not that much has changed since, in 1881, Charles Guiteau borrowed $15 on a whim to buy an ivory-handled revolver that would look good in a museum — he was short a dollar but the store owner, feeling generous, let him have it anyway.)

But part of it is also probably the same reason that, abroad, terrorist organizations like Al-Qaeda and ISIS do so much recruiting from the educated middle classes, especially young men with engineering degrees. It’s the reason that Bryce Williams, who is an exception — a black man who makes the news for a senseless mass shooting — was as far from the “violent inner-city thug” stereotype as imaginable, a former TV news reporter from suburban central Virginia.

There are many kinds of violence and many motivations for violence. I’ve argued before that it’s irresponsible to wave away this issue as “mental illness,” which is generally an excuse to treat the killer’s motivation as a black box whose causes we don’t need to deal with.

But there is a psychological trait that links together this particular kind of violent killer. It’s a trait that’s part of some mental illness diagnoses (like bipolar disorder) and some personality disorder diagnoses (like narcissistic personality disorder) but that I’d argue goes beyond either one. It’s called grandiosity — the idea that you, personally, are the center of the universe, that people ought to be paying attention to you, that you’re entitled to take up space in other people’s lives and their denying you that space is an injustice.

Grandiosity is joined at the hip with privilege. It festers among the subset of our culture that’s taught to take up space, to assert themselves, to make themselves important.

Men commit grandiose mass murders, not women, because it’s women who fear “being too much” and men who fear “not being enough”. The people at the bottom of the heap who spend every day struggling to survive might kill for money, might kill in anger, might kill in self-defense — but to be full of yourself enough that you’d kill for a grandiose cause, to be noticed requires the kind of privilege that comes with a college degree.

The common thread between cultures that lend themselves to grandiose, murderous ideologies is the concept of “honor”, of demanding recognition and respect — whether it be the “honor culture” of fundamentalist Islam or John Wilkes Booth’s seething fury at the thought of living in a society where a black man could freely insult a white man without fear of retaliation. It’s why, in the futile attempt to tease apart any ideological motivation behind Jared Lee Loughner’s attempted assassination of Gabrielle Giffords, the only solid clue that turned up was that at one point Giffords had publicly ignored his question at a Q&A.

This kind of thing has been given other names — “white fragility,” “toxic masculinity.” It’s only a few extreme cases that become mass murders, but this non-negotiable, entitled demand to be paid attention to and taken seriously shows up all over the place.

It’s why men insist on catcalling random women in their field of vision as a sacred right, and become violent when ignored. It’s why a man would burn down his entire social media reputation just to go after a woman for blocking him on Facebook. It’s why intense harassment campaigns spring up to take down people for the crime of creating blocking tools on Twitter.

It’s why someone would threaten a mass shooting or drive someone out of their home over criticism of their favorite video games. It’s why someone would call in a false tip to the police to get someone arrested over not getting a science fiction book award.

It’s not at all new. It wasn’t even new in 1881. But 1881 marked a turning point, where someone who very clearly planned to get famous by creating a media circus over a public act of violence was able to get instant gratification, thanks to the telegraph allowing news stories to “go viral” in a matter of days. When we moved from newspapers to TV news, news stories could go viral in hours; in the Web news era, that shortened to minutes; in the era of social media, the timescale is now in seconds.

I’m horrified that Bryce Williams was livetweeting his own footage of his murders within minutes of the story hitting the headlines — that he waited to shoot himself until after his Twitter and Facebook accounts were suspended, that he very directly sacrificed others’ lives and his own for the immediate dopamine rush of getting hundreds of retweets.

I’m horrified that the video is still up and easily findable on Google. And I’m horrified that when I watched the video — I admit it, I’m human — it was shot to resemble the point-of-view of a first-person shooter video game.

I’m someone who loves social media, and who loves gaming. I’ve staunchly defended both in the past, and I would say the negative things about them are symptoms of broader negative social trends, not their cause.

But I can’t ignore anymore the toxicity that comes with the world of social media or that the gaming world is the birthplace of deranged social movement after deranged social movement — so much so that the biggest terrorist organization in the world, ISIS, uses video game tropes as a recruiting tool — and succeeds in getting Westernized middle-class teenagers to join up so they can feel badass.

I don’t worry about the typical criticisms of social media or gaming. I don’t worry about “shallow” conversational topics or shortened attention spans or graphic depictions of sex and violence.

What I worry about is that these are both tools for feeding narcissism. They’re both ways to create a world that revolves around you, where you’re always the most important person in your world. Twitter is a tool where you can forcibly grab the attention of any celebrity you want and make them listen to your crap, however briefly, at a much lower cost than printing up pamphlets. Gaming creates a culture of people whose favored media always casts themselves as the main character, where they proudly describe themselves as “programmed to win,” who find it utterly intolerable to ever feel irrelevant or powerless.

Whether it’s petty on the level of Twitter harassment or scary on the level of doxing and SWATting or terrifying on the level of outright acts of murder and terrorism, it’s all trolling. And trolling all comes down to the same root — the entitled man who thinks his right to free speech is equivalent to his right to be noticed and heard, and whose reaction to being ignored is to escalate until he can’t be ignored anymore.

To paraphrase a fictional terrorist that all too many angry young men take seriously, yes, way too many of us were taught that we deserved the status of movie stars, rock gods, centers of attention. The natural response to learning that we aren’t is to get pissed off; when the world won’t let us be as big as we feel we are, to lash out and demand to be noticed.

We need to get over that. We need to grow up. We need to learn that as the world grows bigger and more connected that that means giving up the spotlight we were taught we were owed, and that that doesn’t equate to oppression.

Otherwise? Well, Charles Guiteau was arguably the first guy to kill someone just to get on the front page of tomorrow’s newspapers, but he wasn’t the last.

Bryce Williams was the first guy who appears to have killed people specifically to trend for a few minutes on Twitter. He won’t be the last either.