It was getting on toward 2 o’clock on Tuesday morning after the bewildering Iowa caucuses, so I can’t be too sure about anything. As the TV coverage wound down into nothingness, Chris Matthews of MSNBC became increasingly disgruntled about the lack of clear winners and losers in the Hawkeye State, at least in the Democratic photo finish between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders. Getting to hear the losers make concession speeches is what makes our democracy exciting, he insisted. Iowa in 2016, according to the Matthews worldview, was not exciting. “This was just vague,” he muttered.

He may actually have said, “Democracy is vague.” I hope he did. But Matthews looked even more than usual as if he had been sitting on a venomous sea creature for three hours and the toxin was slowly paralyzing his brain. He was pretty difficult to understand and quite likely I am projecting that marvelous observation, which would easily be the most profound thing he has ever said. Brian Williams leapt in with one of those one-word questions that make him the most puckish news anchor ever (in his mind): “Unsatisfying?” And then Rachel Maddow flooded the zone with super-engaged freshman seminar personality: Gosh, she thought it was very exciting that Clinton and Sanders had finished in such a dead heat that people were arguing over whether coin flips and untended precincts had affected the outcome. (Probably not. But also: What outcome?)

But the moment was one of those tiny “tells” where you see something that ought to be obvious. (When we observe the observable, in Joan Didion’s famous phrase.) Democracy is indeed vague, more so than Chris Matthews consciously observes. Its vagueness is not random or without purpose. One might describe democracy, as practiced in the United States at present, as a deliberately vague process meant to obfuscate the machineries of politics and power. When the third-place finisher in an arcane electoral procedure held in 99 Corn Belt counties is the night’s big winner on one side, while the big winner on the other side is the overwhelming favorite who squeaked out a statistically insignificant victory over a left-wing insurgent, it begins to look as if winning and losing are questions of theological exegesis, rather than matters of fact.

It goes without saying that someone like Matthews is only in it for the blood sport, the hurly-burly, the endless pseudo-analytical debate about tactics and strategy and who’s up and who’s down. He barely pretends to care about outcomes or policy. But for him to admit that what he really likes is watching someone lose, seeing those rare moments of honesty and vulnerability (as he put it) in which the manufactured personalities of electoral politics have to go onstage and eat crow — or eat something with the same number of letters as “crow” — was revealing and oddly affecting.

I’m picking on Chris Matthews here because he’s such a glorious manifestation of what’s wrong with political journalism, and in the Tuesday small hours he came off more than a little like a high school football coach in 1986, explaining that soccer will never catch on in America because there are so many ties. (Yes, footy fans, I know the term is actually “draws.”) But that doesn’t mean he’s alone on this, or even wrong. I remember Mitt Romney’s brief and agonized concession speech from 2012, in which it became clear that he had actually drunk the “unskewed polls” Kool-Aid, and believed he was going to win, far better than I remember whatever Obama said. John McCain’s 2008 speech, against the slightly surreal context of some palm-frond plaza in suburban Phoenix, was one of his best moments as a public speaker. (Of course I remember the spectacle of Obama in Grant Park, but not the words that came out of his mouth.)

Hell, I can remember standing there in awestruck teenage horror when Jimmy Carter delivered his concession speech from the White House while it was still daylight outside in suburban California. I remember my dad’s behemoth color TV from Montgomery Ward, whose picture dissolved into indecipherable lines and blotches if you got within 18 inches of the screen. I remember the backyard pool (heated to 76 degrees year round) dappled in November afternoon light while I tried to reckon with the inconceivable fact that the retired movie actor loathed and mocked by my parents and all their friends has been overwhelmingly elected president. Actually, no — most of that is imagination. I’m not sure where I was that afternoon, but I remember the frozen expression on Carter’s face and my own emotions of terror and despair as if it all happened yesterday.

So, yeah — we are storytelling animals who crave moments of hubris, catharsis and crisis. (There’s a reason those words stretch back to antiquity.) Politics is packaged and delivered as unscripted or semi-scripted human drama, and we delight in seeing the mighty brought low, whether that means Don Juan dragged down to hell, Superman enfeebled by Kryptonite or Mitt Romney weepily telling us that his wife would have made “a great first lady.” (Go back and look at it! Throwing shade on Michelle Obama while losing was the consummate Romney douche move, up there with that dog on the roof of the car.) In what may be the masterstroke of English literature, Milton begins “Paradise Lost” with the greatest concession speech of all time, in which Satan faces the scale of his downfall from the “happy Realms of Light” into endless torture and “darkness visible” (“If thou beest he; but O how fall’n! how chang’d”) and vows to keep on fighting a war he can never win.

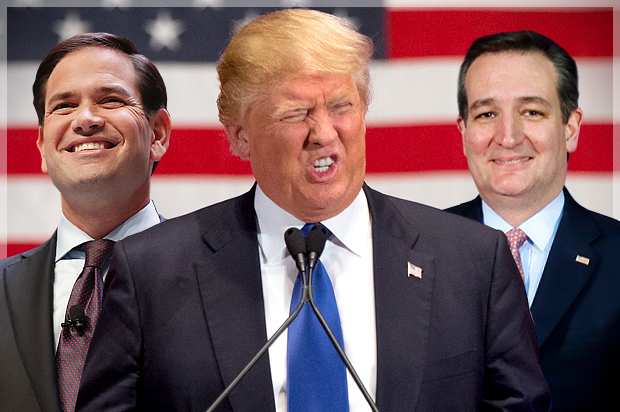

Matthews is right that Donald Trump’s relatively gracious Iowa speech on Tuesday night, after losing a caucus he expected to win (but had previously expected to lose), made the billionaire populist appear more human than at any time in recent memory. If that was a gratifying moment in dramatic terms, it was also a dangerous crack in the Trumpian façade, a glitch in the software package driving his idiot-Nietzschean persona.

Those of us who sit behind computers and write about this stuff have said over and over again that something was the beginning of the end of Donald Trump, and so far we have been wrong. But losing and playing humble about it — in effect, playing by the Chris Matthews rules of politics as theater — is a major blow to the notion that Trump is special and different and unstoppable. If I were advising Trump on strategy and branding, I would tell him to steer the hell away from “more human” and go full Miltonic Satan, although admittedly I might not put it that way. Trump’s supporters don’t want him to say nice things about Ted Cruz and put a happy spin on a disappointing second-place finish. They want “the inconquerable Will,/ And study of revenge, immortal hate,/ And courage never to submit or yield.”

Trump’s true nemesis is the irritatingly angelic visage of Marco Rubio looming up behind him, not the alien entity who actually won in Iowa. Ted Cruz has variously been described as the villain of a movie whose hero is a dog and as a third-grader whose mom bought his clothes out of the Sears catalog. In either case the people who don’t love him hate him worse than plague rats or Hillary Clinton or socialism, and this week’s glorious victory is likely to be the high point of his political career.

As for the diminutive College Republican twerp who just gave the most exuberant third-place victory speech in political history, that sound you heard was the “mainstream conservative” movement coalescing around Marco Rubio with a soft wet thunk, like a bag of dog crap hitting the weird old rich guy’s front door. If Rubio can win in New Hampshire or manage a close second — and Granite State voters are known for such switchbacks — it will suddenly be as if the Trump moment had never happened and the Koch brothers’ Sun King-like reign over the Republican Party had never been threatened.

As for the lack of clarity when it comes to winning and losing on the Democratic side — well, it’s all a matter of perspective, am I right? For leftists and liberals, the choice between Clinton and Sanders comes down to what you make of America’s broken system in the 21st century and whether you think it needs minor repair or an engine overhaul. Who you believe won Iowa reflects a similar division.

If I were explaining European soccer to Coach Matthews in 1986, I would tell him that draws are almost never neutral outcomes. For an underdog playing on the road, they can be inspirational breakthroughs, not to mention unexpected points in the standings. If you are Manchester United or Real Madrid playing at home — which pretty well describes Hillary Clinton’s situation in Iowa — a draw falls somewhere between disappointment and disaster.

Clinton has now been declared the victor in Iowa, albeit by an inconsequential margin. (Not that that is likely to stop the tides and eddies of social-media disputation.) In objective terms, that hardly matters. Indeed, it hardly counts as a fact. But it immediately becomes a central plot element in the Chris Matthews media narrative, evidence that Clinton goes into New Hampshire with “momentum” or, to put it another way, that Man U did not actually draw at home against an obscure provincial opponent. If I were really feeling cynical about this whole spectacle — heaven forfend! — I would say that the pseudo-fact of Clinton’s Iowa victory was not just politically helpful but ideologically necessary. It serves both to bolster and conceal another observable but widely ignored fact, which is that the Democratic Party’s nominating process has little to do with democracy.