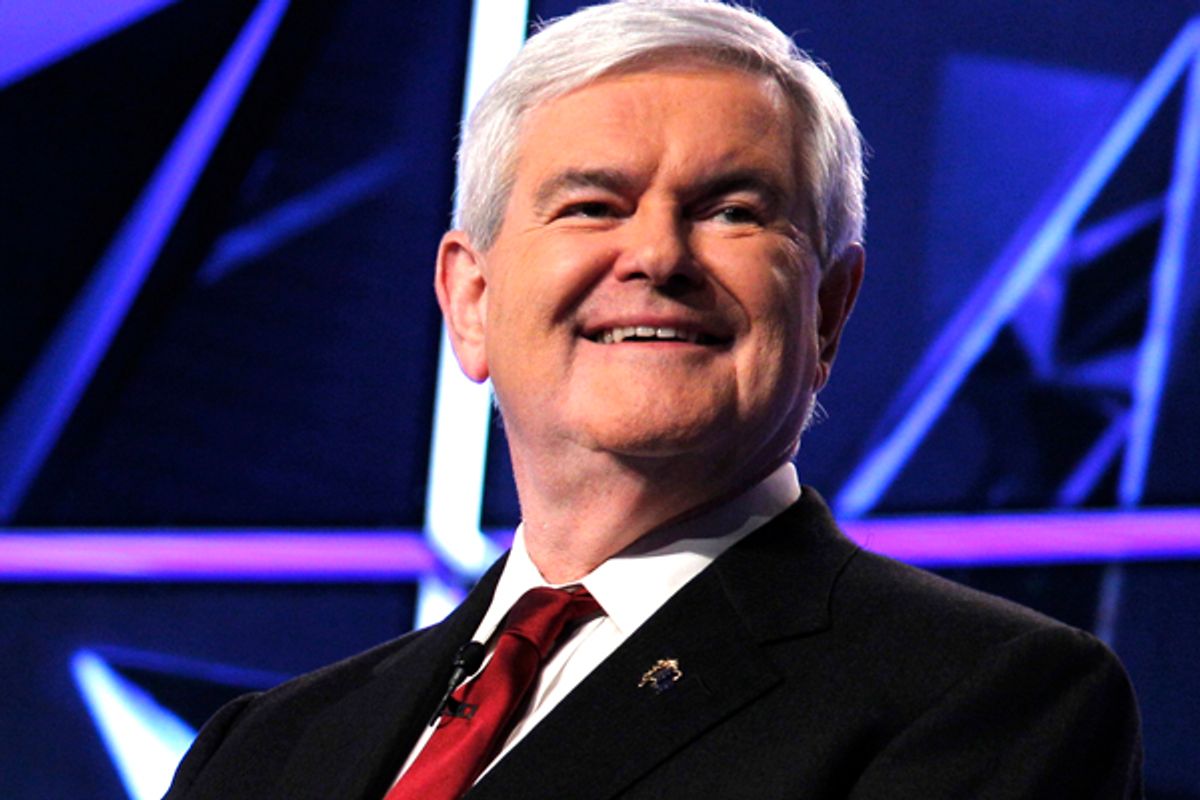

Newt Gingrich, who has surged from single digits to the front of the Republican presidential pack these past few weeks, did something on Tuesday night that Rick Perry and Herman Cain -- the two candidates who stormed to the top before him this fall -- failed to do as front-runners: He turned in a technically strong debate performance. A very strong one.

The former speaker delivered his answers with confidence and force, punctuating them with dramatic pauses and constantly reframing the discussion in grand, bold-sounding terms. A case can be made that Newt is really just selling snake oil, that all of his talk of fundamental change and converging world-historical forces amounts to gobbledygook. But in many ways debates are really just about performance art, and Newt knows how to put on a damn good show for a Republican audience -- a far cry from Perry, who melted down when the spotlight was on him in earlier debates, and Cain, who had little to say and faded into the background when his moment came. For most of CNN's two-hour debate, Gingrich provided a powerful rebuttal against suggestions that he'll soon unravel just like Perry and Cain.

But then came the question about immigration.

Moderator Wolf Blitzer reminded Gingrich that he'd supported Ronald Reagan's amnesty program back in the 1980s, which ended up giving legal status to more than 3 million people, and asked him what he'd do now about the 12 million or so who are here unlawfully. The correct answer to a question like this, according to the Official Tea Party-era Republican Candidate Handbook, is to decry the concept of amnesty, to insist that no one should ever be rewarded for entering the United States illegally, and to rail against the concept of "comprehensive" reform.

This is not the response Newt gave. Instead, he offered a forceful defense of comprehensive reform, arguing that "something like a World War II selective service board" is needed to protect families that may have entered the country illegally but that have established roots and become productive, taxpaying members of their local communities.

"I don’t see how the party that says it’s the party of the family is going to adopt an immigration policy that destroys families that have been here for a quarter-century," Gingrich said. "And I’m prepared to take the heat in saying, 'Let’s be humane in enforcing the law without giving them citizenship, but by finding a way to create legality so that they are not separated from their families.'"

There's a school of thought that this kind of talk will now cause the Newt bubble to deflate rapidly. Today's conservative movement is more rigid and absolutist than ever, and there are few issues that matter as deeply to the average Tea Partyer as immigration. Comparisons are already being drawn between Gingrich's answer and Perry's statement at an earlier debate that "if you say that we should not educate children who have come into our state … by no fault of their own, I don’t think you have a heart.” That defiant claim was widely regarded by conservative opinion-shapers as a poke in the eye and proved to be one of several debate moments that lowered Perry's polling support from around 40 percent to less than 10. Maybe Newt is now in for a similar plunge.

But I wouldn't be so sure. For one thing, it's worth pointing out that Newt's immigration answers were followed by (and in one case interrupted with) loud applause from the crowd. Yes, live debate audiences can be a very misleading barometer, but his lines went over far better with those in the room than Perry's "you don't have a heart" answer.

The reason may be related to salesmanship. Perry is not an artful communicator and his line sounded confrontational; it was the sort of of thing Republicans are used to hearing Democrats say about them. So they responded in kind. But consider the way Newt structured one of his answers on Tuesday night:

If you've come here recently and you have no ties to this country, you ought to go home, period. If you've been here 25 years and you have three kids and two grandkids and you’ve been paying taxes and obeying the law, you belong to a local church, I don't think we’re going to separate you from your family and uproot you forcefully and kick you out.

He hit this same theme several times. It's almost an appeal to tribal loyalty; instead of mimicking a Democratic talking point, Gingrich essentially told the crowd that there are two kinds of illegal immigrants -- the ones who are like us and should be allowed to stay, and the ones who aren't like us and should be kicked out. This seems like a much more effective way of winning over (or at least not riling up) a potentially hostile audience -- especially one that now seems to be looking for reasons to line up with Newt. (A poll released on Tuesday showed him leading Romney 68-25 percent among Tea Party supporters in a hypothetical one-on-one race.) As an added bonus, Gingrich is also now basking in something he's never received before: adulation from the press, which seems impressed with his eloquent defense of comprehensive reform.

Or maybe the simple fact that Gingrich has now staked out amnesty-ish turf will be enough to doom him. After Gingrich spoke, Mitt Romney didn't miss a chance to strike an absolutist posture, declaring that "I’m not going to start drawing lines here about who gets to stay and who gets to go." On paper, there's now a clear, massive advantage for Romney over Gingrich on this issue. But let's see if it translates into anything.

Shares