“When the family breaks down, the economy breaks down,” Rick Santorum intoned in his Iowa caucus “victory” speech Tuesday night (by the time he finished speaking, he’d lost the lead to Romney). Santorum’s bromide showed only a glimmer of the way the conservative “family values” crowd connects America’s worsening economic troubles to the decline of marriage, especially among the middle and working classes. It’s a fascinating worldview that colors the entire GOP primary campaign, in which actual policies to help workers and families are rejected in favor of those that cut government and shackle women to the home, and it needs to be better understood.

It’s also another reminder that the prejudice and disdain Republicans once reserved for African-Americans has spread like a toxic mist to stigmatize a lot of other people, including a lot of white folks. I’ve written about how GOP alarmism over those living off “other people’s money,” a staple of the racial politics that once scapegoated “welfare queens” and “young bucks” buying steak with food stamps, has expanded in the Tea Party years. Now the slackers and moochers and welfare cheats bashed by Republicans include public workers, as well as Social Security and Medicare recipients, people receiving unemployment insurance, plus the 46 million Americans on food stamps, the vast majority of whom have jobs. The vast majority of those new GOP scapegoats are also, by the way, white people.

Now Republicans are taking their judgments about and disapproval of African-American marriage and family patterns and applying them to white people, too. In 1965 Daniel Patrick Moynihan declared a “crisis” in the “Negro family” because “nearly one-quarter of Negro births are now illegitimate,” he wrote. Today the birthrate to white single mothers is even higher – and it’s climbed particularly sharply for white women who dropped out of high school, as well as those who didn’t go to college. Interestingly, rates of divorce and single-motherhood are lowest among the affluent and well educated, and that’s true in black as well as white families.

You might say that all of this data vindicates those who connected the problems of poor African-American families in the ’60s to poverty and discrimination: When times are tough, it gets tougher to find a spouse and stay married. But according to Rick Santorum, you would be wrong. The judgmental family values crowd believes liberals have it backward: Tough times don’t make it harder to get and stay married; when we fail to get and stay married, times get tougher. These are the competing worldviews that are going to vie for primacy no matter who emerges from the GOP primary campaign to challenge Barack Obama, so it’s worth understanding them. According to the Santorum wing of the Republican Party, these new marriage slackers of every race lack not just healthy paychecks, but the bourgeois values that earn them.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

All most people remember about the infamous “Moynihan report,” if they remember it at all, is that it blamed a “tangle of pathology” for the troubles of poor black families headed by single mothers. Moynihan’s analysis said more than that. He blamed African-American poverty on slavery, Jim Crow and enduring racism — in the North and South, de facto and de jure. He showed how historic and persistent black male unemployment and underemployment contributed to the problems of divorce and single parenthood. He also believed welfare for single mothers made the problem worse, and at a time when liberals advocated to expand welfare programs and advance welfare rights, this made Moynihan a conservative, whose ideas about the black family were immediately attacked as “blaming the victim.”

That had always been my take on Moynihan, until I read his entire report, as well as the memo he wrote to President Lyndon Johnson to sell it, just last year. Both have their moments of what we’d call racial insensitivity or ignorance today. But overall, they were a call to address the lasting economic effects of slavery and discrimination that would not be ameliorated by lifting restrictions on voting rights or integrating lunch counters. And if Moynihan thought he could opine freely (some would say offensively) about the troubles of black families, it was because there was little he said in the report that he hadn’t said of his own people, Irish Catholics.

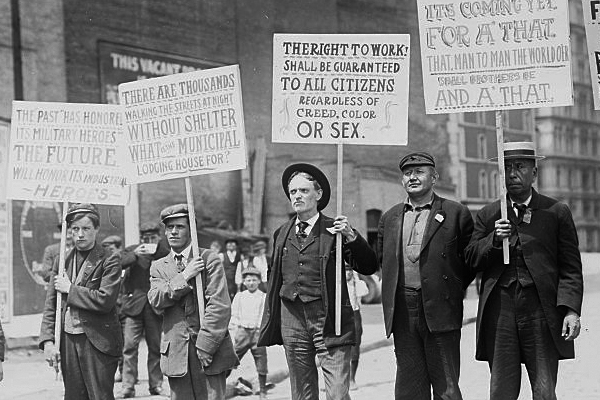

Raised in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen by his mother, after his father abandoned the family, he had seen a lot of what he identified in poor black families in his own community. When he agreed to write the Irish Catholic chapter in “Beyond the Melting Pot,” the 1963 book on race and ethnicity he co-authored with Nathan Glazer, he confessed to Glazer that “for a good while I was interested in the subject only as it provided an explanation for the things that were wrong with the way I was brought up.” And in his report on the black family, he compared their troubles, especially in Northern cities, to those experienced by the rural Irish exiled to urban America 100 years earlier: “It was this abrupt transition that produced the wild Irish slums of the 19thCentury Northeast. Drunkenness, crime, corruption, discrimination, family disorganization, juvenile delinquency were the routine of that era,” Moynihan observed.

For daring to write about the “tangle of pathology” (a term earlier used by the pioneering black sociologist Kenneth Clark) that he saw ensnaring the black family, Moynihan went down in history as a racist. Later, actual racists adapted his work, bringing neither his attention to data nor his commitment to social justice. Charles Murray “proved” that welfare programs destroyed the black family in his influential but deeply dishonest “Losing Ground,” and a generation of conservative scholars blamed black poverty on a preference for welfare over work and sexual freedom over monogamy. Murray and his imitators didn’t bother to notice that welfare rates kept climbing even as welfare benefits got cut back in the ’80s and ’90s – and that they were climbing among white women, too. Something besides the lure of a handout was behind the declining rate of two-parent families of every race.

It took the great black scholar of poverty and work, William Julius Wilson, to flip the focus around, and show how the decline of opportunities for men without college degrees, particularly in the disappearing manufacturing sector, was dampening their chances at getting married and raising children within an intact family. (Wilson, by the way, was a Moynihan defender, lamenting that “the controversy surrounding the Moynihan report had the effect of curtailing serious research on minority problems in the inner city for over a decade.”) He wrote several books outlining his research, but the most exhaustive and influential was his 1996 “When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor.”

In it, Wilson called for an ambitious program of government job creation, but he wanted the programs to be race-neutral; that is, to benefit all groups, not to be expressly targeted to black communities. That was good politics – post-Nixon America hasn’t been inclined to much generosity toward poor black people – but also good policy: Wilson saw that many of the trends affecting black blue-collar workers and those without a college degree were hitting the white working class, too.

Unfortunately, not too many of the white working class or its political representatives paid attention.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Fast-forward about 15 years, and you’ll find a funny echo of Wilson’s book’s theories, and its title, in a 2010 report enthusiastically embraced by conservatives: “When Marriage Disappears: The Retreat from Marriage in Middle America,” a report by the National Marriage Project of the University of Virginia. Far from an homage, the report flips Bill Wilson on his head. The National Review writes about the report and the ongoing work of the National Marriage Project every chance it gets. (Kathryn Jean Lopez last checked in on Valentine’s Day, hoping that on such a holy day, the lonely might finally see the light and immediately form nuclear families, and the restless might remain in them even in these tough economic times.)

“When Marriage Disappears” sounded an alarm about the decline in marriage rates among working-class and “moderately educated” Americans, defined as the 58 percent of adults without a college education, and suggested their economic troubles are connected to their failure to get and stay married. The bold report tried to make this a civil rights issue, decrying “a separate-and-unequal family regime, where the highly educated and the affluent enjoy strong and stable households and everyone else is consigned to increasingly unstable, unhappy, and unworkable ones.” But it ended up drawing some of the same conclusions that old-fashioned conservative “culture of poverty” scolds have drawn about the struggles of black people: It’s the decline of “bourgeois values” like hard work and delayed gratification that makes both marriage and economic security tougher for these people. Only this time, by “these people” they mean a whole lot of white people.

As recently as 1990, the report notes, the non-college educated were more likely to be married by age 30 than those who went to college; now the opposite is true. Birthrates to single women with only high school diplomas more than tripled in the last three decades — from 13 percent in 1982 to 44 percent in 2006–2008. Among women without high school diplomas, the rate of single motherhood jumped from 33 to 54 percent.

The trend is clear among white women: Birthrates to unmarried white women without high school degrees climbed from 21 to 43 percent in that timeframe; to white female high school graduates, from 5 to 34 percent. Only 2 percent of white college-educated women had children in 1982; that climbed only to 6 percent in 2006-08. College-educated parents have also seen their divorce rates fall in roughly the same time period, by a quarter for whites and by more than a third for blacks. (The report provides almost no data about Latino and Asian families.)

“The problem is really in the middle,” its authors explain. “The lower classes have always had higher rates of illegitimacy but that behavior is now climbing into the upper working or solidly middle class – which is also suffering from declining wages and higher unemployment.” They acknowledge that economic troubles could be taking a toll on the marriage and family formation of working- and middle-class folks, even citing William Julius Wilson’s work finding that “men who are not stably employed at jobs with decent wages are viewed — both in their own eyes and in the eyes of their partners — as less eligible marriage material and as inferior husbands.”

But despite a few nods to higher unemployment and declining wages for the “moderately educated” middle, the real problem in “When Marriage Disappears” seems to come down to values. The authors lament the trend toward premarital “cohabitation” and the “soul mate” vision of marriage, and the increased acceptance of divorce and premarital sex.

Moderately educated Americans are markedly less likely than are highly educated Americans to embrace the bourgeois values and virtues—for instance, delayed gratification, a focus on education, and temperance—that are the sine qua nons of personal and marital success in the contemporary United States. By contrast, highly educated Americans (and their children) adhere devoutly to a “success sequence” norm that puts education, work, marriage, and childbearing in sequence, one after another, in ways that maximize their odds of making good on the American Dream and obtaining a successful family life. Their commitment to the success sequence also increases the odds that they abide by bourgeois virtues like delayed gratification.

Put another way, we’re all lazy, oversexed, instant-gratification-seeking grifters now. Even white people.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

I can’t think of a better example of today’s lingering culture war than the contrast between “When Work Disappears” and “When Marriage Disappears.” Liberals are inclined to believe that decent jobs, economic security and good education encourage marriage and intact families; conservatives say marriage and intact families lead to decent jobs, economic security and good education. I don’t pretend that there’s no connection between values, family structure and economic success: Wilson acknowledged that long-term poverty was made more intractable by the family troubles, drug and alcohol abuse, delinquency and crime that often go along with it; Moynihan made the same point about the “wild Irish slums” of 150 years ago. But that’s very different from believing that personal behavior is the primary cause of economic distress, rather than a factor that can worsen it.

But blaming the poor for their own poverty and suffering is a time-honored conservative pastime, and in our increasingly stratified, economically unequal multiracial society, the doctrines that justify inequality and suffering must be updated. Now, people devoted to racialist views look at the rise in white poverty, unemployment, divorce and single-parenthood rates and try to blame the problems of moderately educated white people, particularly white men, on affirmative action, immigration and feminism. Check out Pat Buchanan’s last book.

Still, while racism persists on the right – witness Newt Gingrich’s slurs about the NAACP and food stamps and his slurring President Obama as “the food stamp president” – it’s remarkable to see how readily conservatives have found a way to blame economically struggling Americans for their own plight, even when most of them are white. It’s why Santorum could change gears so easily last week when confronted with his “black people” comment, from allowing he might have said it to claiming he “probably” didn’t: “I’ve been pretty clear about my concern for dependency in this country and concern for people not being more dependent on our government, whatever their race or ethnicity is.” That’s actually true.

Of course, Santorum does have one scapegoat for the breakdown of the family, and it’s “radical feminism.” As he wrote in his 2005 book “It Takes a Family” (a rejoinder to Hillary Clinton’s “It Takes a Village” nine years earlier) the number of stay-at-home mothers has declined sharply not because of an economy that requires two paychecks, but “radical feminism’s misogynistic crusade to make working outside the home the only marker of social value and self-respect.”

I’m a feminist, but even I think the rollback of New Deal liberalism and resurgent free market fanaticism had more to do with women entering the workplace than the women’s movement did. The relationship between feminism and changing family structure is hugely complicated, resisting simplistic chicken-egg platitudes. Nineteenth-century industrializing America drew women into the workplace at least partly because they’d work for less money and because many new jobs required less brawn. Then, once they were there, many enjoyed the freedom from the tyranny of compulsory marriage and servitude that earning their own money provided. The postwar “feminine mystique” identified by Betty Friedan couldn’t reverse the steady progress of women’s independence. But the dismantling of the wage-and-benefits consensus that prevailed after the Great Depression and the war, and the return of free-market fundamentalism, forced at least as many mothers out of the home as feminism did.

Ignoring the economic forces keeping women in the workplace, Santorum and his allies want to force them back. The most powerful force on behalf of women’s freedom is of course contraception, so Santorum would do away with it, even for married couples. Other conservatives wouldn’t go that far – even Mitt Romney thought it was safe to say in Saturday’s debate, “Contraception? It’s working just fine, leave it alone.” Still, for a while the GOP primary seemed to include a family-size competition, with Santorum and Jon Huntsman boasting of their seven kids to Romney’s five and Michele Bachmann’s five plus 23 foster kids. The modern Republican Party believes in a world in which women are expected to have children early and often. (Only Gingrich believes in marrying early and often.)

Even supposedly open-minded modern conservatives share a belief that the erosion of American living standards is at least partly caused by the erosion of marriage. Santorum admirer David Brooks thinks one answer is “a government that both encourages marriage and also supplies wage subsidies to men to make them marriageable.” We currently provide subsidies to low-wage workers, by the way, through the Earned Income Tax Credit; is Brooks suggesting men get a little extra in their check? Anything’s possible. Brooks concluded his freaky pro-Santorum column by telling us “America is creative because of its moral materialism — when social values and economic ambitions get down in the mosh pit and dance. Santorum is in the fray.”

We are all in the fray. That’s the creative genius of American conservatism: It always advances “social values” that defend the “economic ambitions” of the very rich and blame the non-rich for their inability to prosper. Moral materialism, indeed. Santorum is coming down from his Iowa high, despite the best promotional efforts of Brooks, but his belief in the moral decline of the American middle is widely shared within his party. Here’s hoping the white working-class voters he was supposed to lure to the GOP finally realize the truth about Santorum’s party: All those old stereotypes about the moral and personal failings that kept black people from getting ahead now apply to them, too.