Karl Marx’s famous maxim that history repeats itself, first as tragedy and then as farce, can apply just as well to the history of ideas as to the political sphere. Consider the teapot-tempest over religion and science that has mysteriously broken out in 2014, and has proven so irresistible to the media. We already had this debate, which occupied a great deal of the intellectual life of Western civilization in the 18th and 19th centuries, and it was a whole lot less stupid the first time around. Of course, no one on any side of the argument understands its philosophical and theological history, and the very idea of “Western civilization” is in considerable disrepute on the left and right alike. So we get the sinister cartoon version, in which religious faith and scientific rationalism are reduced to ideological caricatures of themselves, and in which we are revealed to believe in neither one.

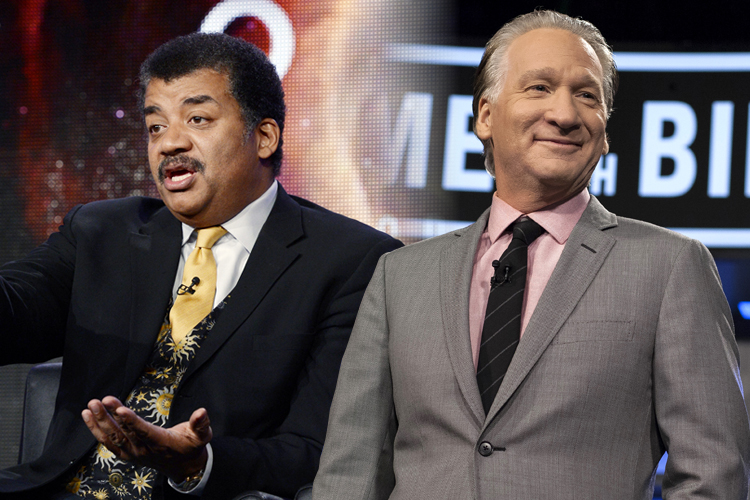

Young-earth creationism, a tiny fringe movement within Christianity whose influence is largely a reflection of liberal hysteria, is getting a totally unearned moment in the spotlight (for at least the second or third time). Evangelist Ken Ham of the pseudo-scientific advocacy group Answers in Genesis gets to “debate” Bill Nye the Science Guy about whether or not the earth is 6,000 years old, in a grotesque parody of academic discourse. Ham’s allies, meanwhile, complain that Neil deGrasse Tyson’s new “Cosmos” TV series has no room for their ludicrous anti-scientific beliefs. If anything, Tyson’s show has spent a suspicious amount of time indirectly debunking creationist ideas. They seem to make him (or, more properly, his writers) nervous. Not, as Ham would have it, because somewhere inside themselves these infidels recognize revealed truth, but because religious ecstasy, however nonsensical, is powerful in a way reason and logic are not.

Everyone who writes a snarky Internet comment about why the T-Rex couple didn’t make it onto Noah’s ark betrays the same nervousness, and so do earnest Northeast Corridor journalists who rush to assure us that Ham’s elaborate fantasy scenarios about fossils and the Grand Canyon are not actually true, and that we would all find science just as wonderful as religion if only we paid attention. (Such articles strike me as totems of liberal self-reassurance, and not terribly convincing ones at that.) Repeating facts over and over again doesn’t make them any more true, and definitely doesn’t make them more convincing. I suppose this is about trying to win the hearts and minds of some uninformed but uncommitted mass of people out there who don’t quite know what they think. But hectoring or patronizing them is unlikely to do any good, and if you believe that facts are what carry the day in American public discourse then you haven’t paid much attention to the last 350 years or so.

This creationist boomlet goes hand in glove with the larger political strategy of Christian fundamentalism, which is somewhere between diabolically clever and flat-out desperate. Faced with a long sunset as a significant but declining subculture, the Christian right has embraced postmodernism and identity politics, at least in the sense that it suddenly wants to depict itself as a persecuted cultural minority entitled to special rights and privileges. These largely boil down, of course, to the right to resist scientific evidence on everything from evolution to climate change to vaccination, along with the right to be gratuitously cruel to LGBT people. One might well argue that this has less to do with the eternal dictates of the Almighty than with anti-government paranoia and old-fashioned bigotry. But it’s noteworthy that even in its dumbest and most debased form, religion still finds a way to attack liberal orthodoxy at its weak point.

Things can’t possibly be as bad on the scientific and rationalist side of the ledger, but they’re still confused and confusing. Tyson has made diplomatic comments about science and religion not necessarily being enemies, a halfway true statement that was never likely to satisfy anybody. (Meanwhile, “Cosmos” thoroughly botched the fascinating and ambiguous story of Giordano Bruno, a cosmological pioneer and heretical theologian burned by the Inquisition.) Tyson was clearly echoing Stephen Jay Gould’s 1997 pronouncement that the two domains were “non-overlapping magisteria,” meaning that science is concerned entirely with empirical questions and religion with questions of morality and ultimate meaning. Even at the time Gould admitted he was being strategic and trying to uphold the social status of science in a deeply religious nation (although he also defended his doctrine on philosophical grounds). At best, he was outlining a tentative truce between certain areas of scientific inquiry and a certain strain of up-market orthodox Christian and Jewish theology — the once-dominant tradition of St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas — that has been willing to accommodate scientific discovery and has tended to avoid unequivocal pronouncements about the nature of reality.

Creationists and other Biblical fundamentalists, needless to say, are having none of it: For them, the empirical realm is always and everywhere subservient to the revealed word of God. Meanwhile “New Atheists” like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, along with their pop-culture sock puppet Bill Maher, espouse a similar view from the other direction. Their ahistorical or anti-historical depiction of religion is every bit as stupid as Ken Ham’s. Since there is nothing outside the empirical realm and no questions that can resist rational inquiry, the so-called domain of religion does not even exist. These debased modern-day atheists conflate all religion with its most stereotypical, superstitious and oppressive dogmas – a mistake that Nietzsche, the archangel of atheism, would never have made – and refuse to acknowledge that human life possesses a sensuous, symbolic and communal aspect that religion has channeled and accessed in a way no other social practice ever has. Strangely, their jeremiads urging the sheeple to wake from their God-haunted torpor haven’t won many converts.

As the Marxist cultural critic Terry Eagleton puts it in his new book “Culture and the Death of God,” Dawkins and his new-atheist peers are “old-fashioned 19th-century rationalists,” whose arguments rest upon a post-Kantian theological dodge, in which reason and the scientific method are enthroned in the space formerly occupied by God and defended with a flaming sword. For them to argue that religion is “a set of erroneous propositions,” Eagleton notes (citing Emile Durkheim, who was no believer), is a fundamental misjudgment, like claiming that the death of Cordelia in “King Lear” cannot possibly move us to tears because she’s not a real person. Religious doctrine may well be false or sinister and is certainly mythological, but it is also “a power that moves us to action in ways of which Reason alone is incapable.”

It’s not surprising that reporters and pundits are drawn to young-earth creationists and New Atheists alike. (I interviewed Ken Ham years ago, for a story about the links between New Age pseudo-archaeology and Christian fundamentalism. He knew what I wanted and delivered it.) Powerful convictions of any kind are highly seductive, especially in a bewildering and rootless age when consumption is the only absolute good, an age adrift between permanent skepticism and boutique belief. (As Eagleton quips, “those who cannot conceive of an end to Wall Street are perfectly capable of believing in Kabbalah.”) While Ham’s beliefs are avowedly irrational and Dawkins claims to represent absolute rationality, both come off as passionate extremists within the cool, denatured, post-ideological space of the mass media — where in any case there is no obvious difference between those things.

So on one hand we have atheists whose views would have seemed old-hat under Queen Victoria but who see themselves as representing the apex of progressive modern thought, and on the other we have a modern twist on religion that pretends to be ancient or traditional. Biblical fundamentalism as we know it today is essentially a 19th-century British invention that took root among white rural Americans much later than that. William Jennings Bryan, although revered as a forefather by today’s creationists, would have had nothing in common with them politically and very little theologically. (Bryan would have told you that the Bible was “true,” but he didn’t mean that God created the universe in six literal 24-hour days.) Islamic fundamentalism, the particular bugaboo of Dawkins and Harris, is more recent still, a metaphysical uprising against late modernism and the global force of Western consumer culture.

It would be foolish to deny that fundamentalism is or can be dangerous, but the liberal intelligentsia compulsively exaggerates the danger posed by the likes of Ken Ham or Pat Robertson, who are deemed to be plotting the theocratic overthrow of the republic when in fact they represent a marginalized constituency with little power. Fundamentalists oppose the science of climate change on supposed scriptural grounds, for instance, but on that issue they’re just serving as handmaidens to corporate money and power. In much the same way but on a larger scale, conservatives and government apparatchiks interpret the scattered and disparate actions of al-Qaida and its allies as an apocalyptic threat that justifies secret drone wars, unknowable levels of surveillance and the expenditure of countless billions.

Eagleton claims that our “post-theological, post-metaphysical, post-ideological [and] even post-historical era” is reacting with intense anxiety to the rise of a renewed fundamentalism, and the news flash that God isn’t dead after all. But he’s writing from the context of Britain, one of the world’s most thoroughly secularized societies. The American dilemma lies in the fact that we’re not post-anything. The Enlightenment never entirely took hold on this continent, as Thomas Jefferson accurately predicted, and the faithlessness or supermarket spirituality of consumer culture coexists uneasily with intense religious feeling and intense mythological nationalism. If Americans keep fighting the old philosophical battle between faith and reason over and over again, in increasingly silly forms, that reflects an unresolved spiritual contradiction at the core of our national identity. We long to be a shining city on a hill but cannot build it; we long for a mystical synthesis of science and religion but cannot find it.