My grandmother was the wisest person I have ever known. She had a fifth-grade education. She lived under and survived the terror regime of Jim and Jane Crow in the South. She and my grandfather owned a small farm — they were not sharecroppers or tenant farmers. They raised many children related to them by blood or marriage: nieces and nephews, younger cousins and so on. They also took in the children of neighbors and other people who, for whatever reason, needed help. No one was turned away if they needed food or a place to stay. Many of the children my grandparents cared for went on to become doctors, bankers, teachers, lawyers and morticians.

My grandmother also offered prophecies and interpreted dreams. What she foretold and interpreted almost always came to pass. I wish I had listened to her more than I did. Sometimes prophecies and predictions must be forced into being; outcomes are never preordained. That is the riddle and paradox of such things.

My grandmother was also a master storyteller. She would make strange faces and change her voice to become the monsters, shape-shifters and other strange entities she told me about that haunted the woods, roads and swamps of North Carolina when she was a child.

One of my favorites was about the Goat Man who prowled the backwoods and dirt roads in little towns all across the South.

In fact, my friend, the author Joe Lansdale, knows of the Goat Man too. He recently wrote a story for Halloween about him: “The Tall Tale of the Sabine River Goat Man and the Haunted Cemetery.”

My grandmother told me that the Goat Man would scream and howl while galloping through the town where she grew up, clomping on his flaming, hoofed feet during the twilight hours between day and night. His awful noises were a warning for all to keep away, an announcement that the Goat Man was here and there was not a damn thing you or anyone else could do about it. If he wanted to get you, he would.

RELATED: How higher education can win the war against neoliberalism and white supremacy

The Goat Man grabbed little Black boys and Black girls and put them in a sack and stole them away into the night. Maybe he ate them or tortured them to death for his own amusement. Maybe it was even more horrible than that.

My grandmother would always scare me with that part of the story, but she’d tell me the really good part was coming up, so I’d best pay close attention.

One day the tough and proud Black men in the town decided to kill the Goat Man — assuming that such a thing was even humanly possible. They told some of the teenage boys to walk on the road at dusk, when the Goat Man was sure to come after them. Then they were supposed to run up to the barn where the posse was waiting. The plan was going perfectly, she explained. The Goat Man, so bold, took the bait and ran after the boys to that barn before realizing it was a trap. Then he stood there, so damn arrogant, telling them all to come out or he was gonna gobble every single Negro up, including the adult men, and maybe, if his belly got too full, save the other Negroes for a snack.

My grandmother started to laugh at that point. She told me that the Black men finally had enough of his mess and jumped on the Goat Man. They kicked and pummeled him. They shot him with their hunting rifles and shotguns. They beat him with chains and axe handles and anything else they thought would brain him. But that Goat Man was tough and strong with evil. He tore one man’s arm off. He took one of the teenage boys and kicked him so hard that “his privates,” as my grandmother put it, came out of his mouth and nose. He grabbed one member of the posse, ripped his head clean off his shoulders and threw it out into a field. Apparently, that man was a loudmouth, a troublemaker and a bully, and no one was terribly sorry when the Goat Man killed him.

Finally the Goat Man ran away with that posse of Black folks chasing after him. The Goat Man never came down that dirt road again. People claimed they could still hear him, in the woods or deep in the swamp. But people stopped randomly disappearing. Parents used the story of the Goat Man, naturally enough, to scare children into behaving. When I asked my grandmother what really happened to that Goat Man, she leaned in, lowered her voice, and said sternly and clearly that he was still out there, just waiting for the right time to come back. “Monsters like that never really go away,” she said.

Years later, while reading Lawrence Levine’s book “Black Culture and Black Consciousness,” I felt that I finally understood the wisdom and truth of my grandmother’s Goat Man stories. Those terrifying tales were (and still are) a way for adults to teach Black children how to survive Jim and Jane Crow white supremacy and the other injustices they would suffer throughout life because of the color of their skin.

The Goat Man’s howling was the sound of curfews and sundown towns and police sirens. His fiery, strange appearance was like that of the Klan members and other white mobs with their torches and lynching ropes and other forms of racist terror. At their core, the Goat Man and other such monsters were a reminder that real evil takes the form of flesh-and-blood human beings, not ghosts or demons or spectral fiends.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

The Age of Trump has empowered human monsters. As much as many people wish these were phantasmagoric bogeymen, they are real monsters, with a plan to remake America in their own evil vision.

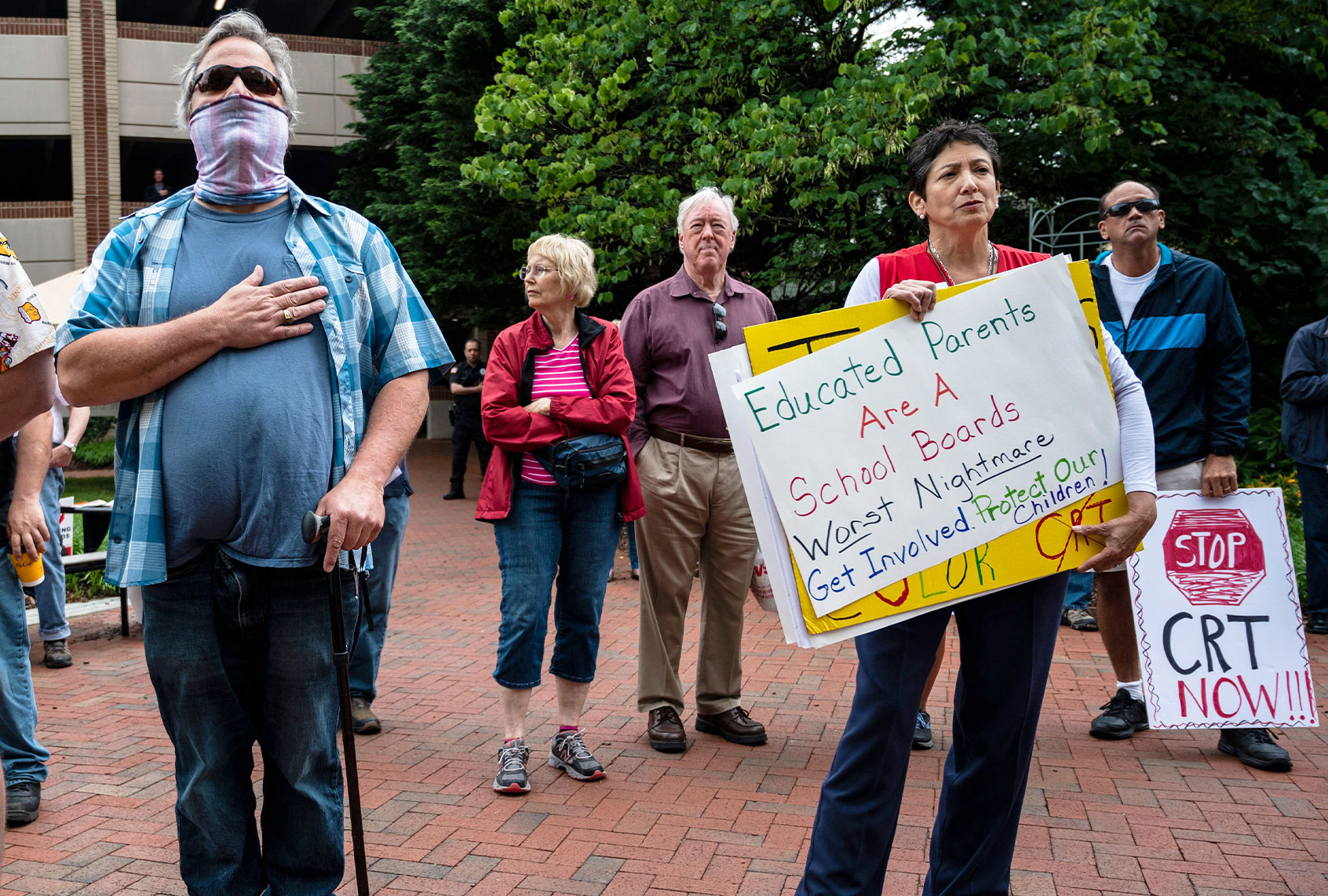

Their goal is to reclaim uncontested white power and white privilege over every significant aspect of American society. Their evil fairytales about “critical race theory” or “parental control” are but a means to that end. The real meaning of those words does not matter; the emotions and the behavior they encourage is what is important. Indeed, for fascists and other authoritarians, reality and truth are mere functions of power, arbitrary constructs that can be changed to meet the needs of the leader and the movement.

The right-wing propaganda machine’s version of “critical race theory” is a lie, an empty floating signifier that can be made to mean almost anything the propagandists and their audience want it to. Once objective truth and reality are destroyed or abandoned, democracy and human freedom become impossible.

What about the everyday white folks, regular people who are not of the political class and not deeply knowledgeable about public policy — for example those who voted for Republican Glenn Youngkin in Virginia last week because of claims about “critical race theory” or “the woke socialist Democrats” or whatever else?

Those people are doing the work of racism and white supremacy. Of course, a great many of them, perhaps most, would take great umbrage at such a description. But on these matters, intention is irrelevant.

Supporting Republican fascists who tell evil fairytales about “critical race theory” — or, more directly, about the teaching of America’s real history — is by definition an act of white supremacy and racism.

I have no doubt that many white people alarmed about “critical race theory” have their own intergenerational family stories about some version of the Goat Man — memories of terror and resistance and being abused by the powerful and privileged. Those stories may stem from histories of poverty or perhaps being sharecroppers or small farmers who lost their land or their homes to crooked banks. Everyday white folks in the Rust Belt and other parts of post-industrial America definitely have stories of how big corporations and gangster capitalists reduced them to misery and destroyed their communities.

Many everyday white folks also have stories about how their ancestors lived in mining towns and were paid in script and abused by the Pinkertons or company goons. And of course, there is the white ethnic fable — partly true and partly fantasy — about how their ancestors survived hardship in Europe and came to America with “nothing,” and then rose by “working hard,” making it to middle-class affluence with “no help” — unlike certain “lazy” or “undeserving” others, who for the most part already lived here.

Somewhere along the way too many everyday white folks in America lost or forgot what the real lessons from their personal and family stories about disempowerment and hardship. They learned or decided that it was preferable to side with the powerful — and in time, perhaps, even join their ranks — than to ally with those who are oppressed and marginalized and work together to make society better for everyone.

Many historians and others who study the history of white folks and the color line have described this as “the price of entry” into the collective notion of whiteness (a relatively recent invention) and all the material and psychological privileges that come with it.

Those bargains of whiteness — and the type of anxious and paranoid white identity politics and white rage that all too often follow them — have helped to create America’s current condition of existential peril. In effect, and in many cases in reality, they have created monsters.

Decent Americans — and especially sheltered and privileged white liberals — still need to prepare themselves for what is likely next in our country’s downward and spiral into neofascism. Too many Americans are still fueled by antiquated fairytales about American exceptionalism, and the naive notion “it can’t happen here,” in the indispensable nation, supposedly the greatest on Earth.

Understand this: America’s fascist monsters are real. Unlike the Goat Man, they are not metaphorical. They are coming to get you and destroy democracy. They will not stop until they devour all that is good in America or are completely vanquished. Get ready.

More from Chauncey DeVega on the resurgent white supremacy of the Trump era: