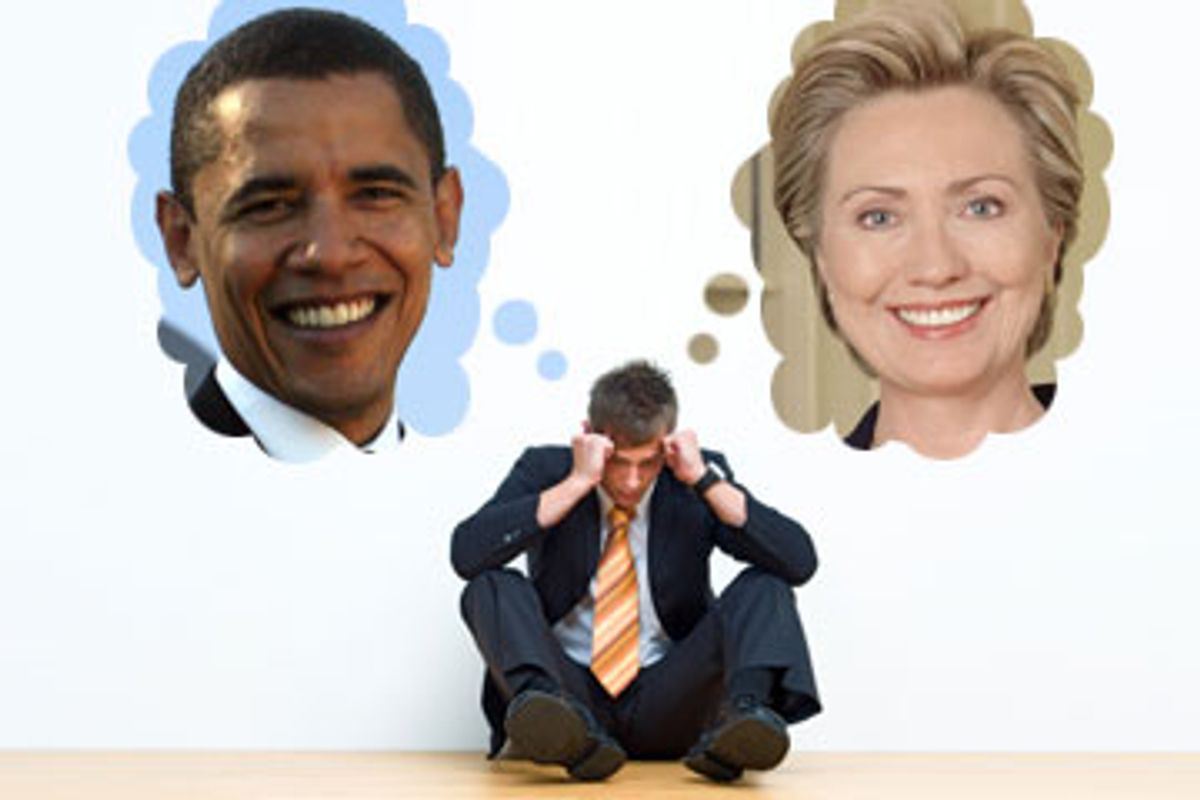

Richard Ray, one of 285 remaining uncommitted Democratic superdelegates, has a new joke that he's been trying out on friends. "I told somebody -- I was kidding with them -- I had a dream last night," said Ray, the president of the Georgia AFL-CIO. "I said I dreamed that all the primaries were over and we were at the convention, and we were taking a roll call, and for whatever reason it was tied and I had to cast the deciding vote. And I woke up in a sweat." Ray laughed and then added, "I don't want that responsibility. No thank you."

There is a common assumption, particularly among passionate supporters of front-runner Barack Obama, that the unelected superdelegates to the Democratic Convention are waiting for an excuse to defy the wishes of rank-and-file voters and install Hillary Clinton as the Democratic nominee. In truth, there is scant evidence that the 795 superdelegates (mostly members of Congress and the Democratic National Committee) who automatically go to the convention in Denver this August are reveling in their sudden importance. A member of the U.S. House of Representatives from the Southwest also spoke with trepidation about the recurring nightmare of casting the deciding vote at the convention. "My God, I don't want that," he said. "I don't know anybody who is looking forward to that."

In fact, most of the uncommitted seem like the gawky kids on Little League teams who silently pray on every pitch, "Please God, don't let them hit it to me." But with Clinton gaining in Indiana and North Carolina thanks to Obama's recent troubles, the odds increased at least a little bit this week that the ball might be hit right at them.

Most undecided superdelegates Salon interviewed this week wanted to see Democratic voters in the remaining primary states cast their votes before they weigh in. Even though Arizona handily went for Clinton in its Feb. 5 primary, the state's Democratic Party chairman Don Bivens says he believed that it was premature to make an endorsement immediately after the contest. "The fact that we voted on Feb. 5 was just serendipitous," Bivens said. "We could have just as easily been June 5, and I feel like the voter on June 5 counts just as much as the beginning."

Now Bivens knows what it's like in those final states, where every last vote matters. Just this week, he's been courted personally by Obama and Bill Clinton. In a phone call to lobby Bivens for his vote, Obama suggested paying close attention to the vote totals out of Tuesday's Indiana primary. According to Bivens, Obama's pitch was: "Well, I'm ahead, there's very little prospect that these numbers are going to move much. No matter what, nothing much is going to change." Meanwhile, Bill Clinton also urged Bivens to study the Indiana returns. The Arizona party chairman said the former president instructed him, "Watch that white middle-class vote, that's what's going to win it for us in November."

Most of the uncommitted superdelegates want to stay that way as long as possible. While there has been a steady drip-drip flow of superdelegates to Obama over the last two months -- all but erasing Clinton's initial advantage among these party leaders -- the largest subgroup remains uncommitted. According to the latest Associated Press tally, 285 are uncommitted, while 263 support Clinton and 247 are backing Obama, including former national party chairman Joe Andrew, who jumped from Clinton to Obama on Thursday. While some Obama supporters like first-term Missouri Sen. Claire McCaskill have claimed that most of the neutral superdelegates are secret Obama-supporters reluctant to directly confront the Clintons, an equally persuasive guess is that the bulk of these fence sitters are what they purport to be -- Democrats desperate for conclusive proof about the identity of the strongest candidate against John McCain.

Many of those still on the fence are state party chairs and vice chairs who had promised to stay neutral. An emblematic case is Robin Carnahan, who is running for a second term as Missouri's secretary of state, and is the top-ranking election official in a state whose primary went for Obama by just 9,000 votes.

For superdelegates, most of whom are active politicians, to choose is to lose the support of either the Obamaniacs or the Hillary-ites in their state or district. "I don't want to alienate anybody, period," said the Democratic House member from the Southwest, whose district went for Obama but whose state opted for Clinton. The congressman, facing a competitive reelection race in November, explained, "I come from a district that is a Republican district. I've got to win independents. I need to win Republicans ... I think it helps me, in my own district, not to say anything." Even before the latest round of controversy over Obama's former pastor Rev. Jeremiah Wright, this House member worried that if he endorsed for president, he would be blamed for something his candidate said or did.

Four-term Rep. Rick Larsen, from a district in northwestern Washington state that went for Obama, says he's not thrilled about attending the convention. "Four days in Denver hiking and fishing, I'm all in," Larsen said. "Four days in Denver going to a convention? It's not at the top of my list."

The superdelegates were created by the Democrats before the 1984 primaries, and aside from putting Walter Mondale over the top in 1984, they have been an irrelevant wrinkle in party rules until now. But few Democrats ever envisioned that they would make a difference in 2008, a campaign year when the nominee was expected to be selected amid the flurry of Feb. 5 primaries and caucuses. It was not until mid-March, after Obama failed to clinch the nomination by losing the Ohio and Texas primaries, that Larsen realized he could be casting a decisive vote. "Early on it dawned at me I didn't like being a superdelegate," he said. "The whole process of superdelegates was created to make sure that [elected] delegates didn't do anything too rash -- as if they need a bunch of know-it-alls telling them what to do."

Most uncommitted superdelegates recognize that they may be forced to make a decision on a nominee in the best interests of the Democratic Party. Even if Obama sweeps all the remaining primaries, he will not have enough elected delegates to win the nomination without a boost from the remaining undecided superdelegates. But for the most part, these neutral superdelegates do not see the logic behind a rush to judgment now, since the primaries will likely drag on until Montana and South Dakota vote on June 3. As Iowa Democratic chairman Scott Brennan, whose state got the ball rolling with Obama winning its Jan. 3 caucuses, put it, "My intention is to wait until all the primaries are over and to let the rest of the Democrats, independents and a significant number of Republicans speak. And then to see what the lay of the land is at that point."

A sweep by Obama of the Indiana and North Carolina primaries Tuesday could change everyone's calculus. "If one of the candidates wins both those states, I think it does become a game-changing day -- and it's going to push a lot of superdelegates to a faster decision," said Larsen, the undecided Washington congressman. In the end, superdelegates appear to want what almost everyone else in the game (the candidates, their staffs, party leaders and the press) craves -- a decisive result. "I guess I hope that one candidate or the other in a sense says, 'Yep, the other guy won,' and lets it go at that -- pretty much what happened with the Republicans," said the House member from the Southwest, sounding wistful. "I don't know if it's going to happen."

But all bets are off if Tuesday offers a split verdict, and Clinton gains enough support in the closing month to close her gap with Obama to, say, 100 pledged delegates. This would be a formula for the fight to go all the way to the Denver convention.

And at that point, it would not only be the superdelegates who were in play. A little-known loophole in Democratic Party rules potentially frees up every delegate -- even those selected in primaries and caucuses -- to shift their allegiance at the convention. All that delegates are required to do is to "in all good conscience" reflect the sentiments of the voters who chose them. For delegates with flexible consciences, the sky is theoretically the limit. "The press is wrong in exclusively focusing on the superdelegates," says a member of the Democratic National Committee, who has closely studied the convention rulebook. "If it goes to the Convention, everybody's up for grabs."

Small wonder that so many prominent Democrats are fantasizing about clarity while nightmare scenarios dance in their heads.

Shares