Utter the words "right wing" to your typical liberal, and he or she is likely to conjure up a Bosch-like inferno of white sheets, helmet-haired blonds and pollution-loving robber barons. Far be it from me, a mere arts journalist, to suggest that this gaudy image, however satisfying, does considerable injustice to a complicated phenomenon. But liberals also do themselves an injustice by remaining content with such a distorted semi-fantasy.

They deprive themselves of the provocations and contributions of some first-class thinkers and writers who have found a place on the right. Agree or disagree with such writers as Florence King, Richard Brookhiser, James Buchanan, Gertrude Himmelfarb, Francis Fukuyama, Milton Friedman, Kenneth Minogue, James Q. Wilson and Roger Scruton, you're almost certain to find more stimulation from wrestling with their arguments and points than you are from dozing through yet another recital of the familiar old lefty credos.

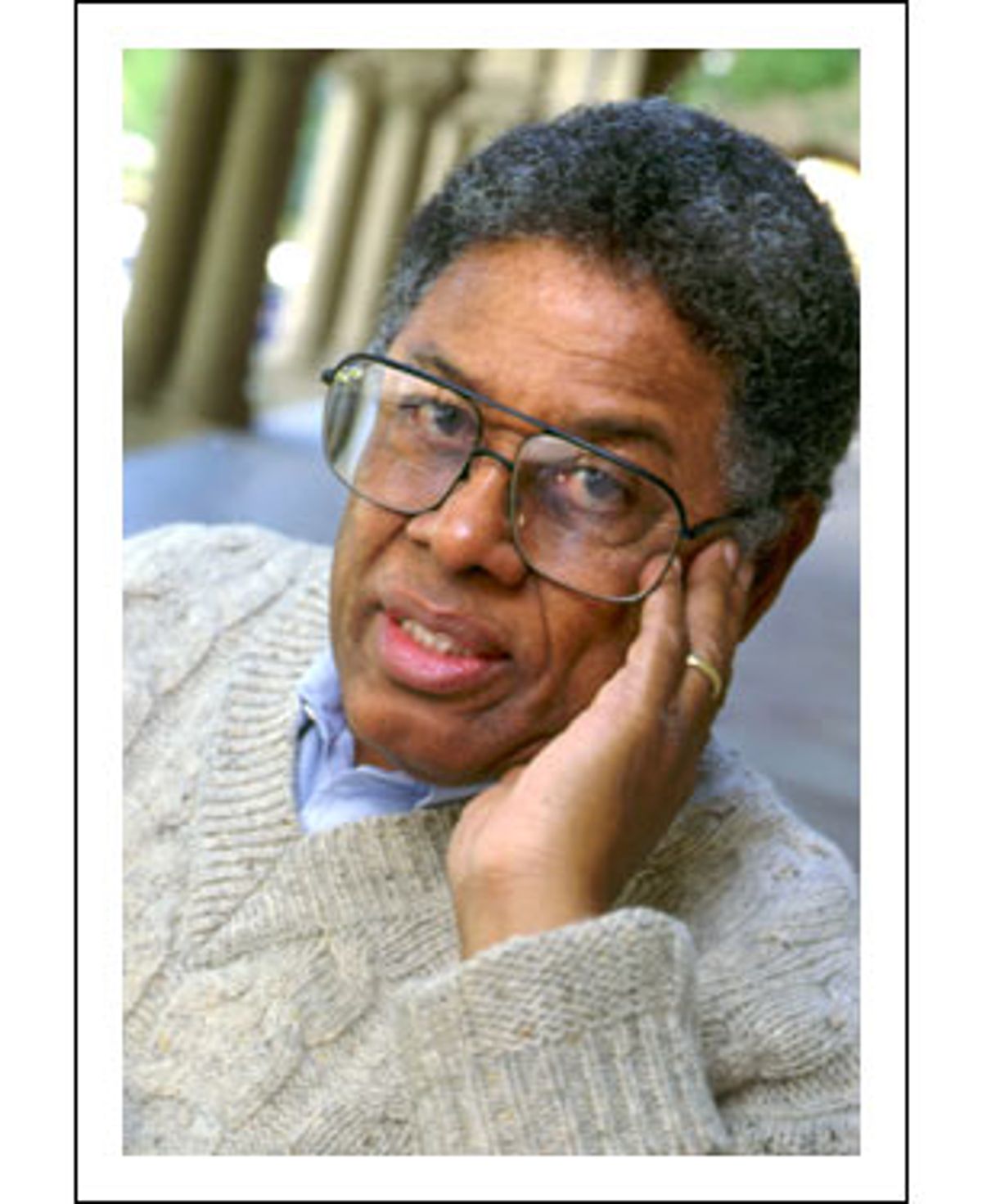

Add to that list the economist Thomas Sowell, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. He is, let it be said right now, generally described as a "black conservative." While some reviewers have dismissed Sowell's writings as the biased product of a rigid ideologue, I suspect that many readers are likely to find his thinking remarkably reasonable, his arguments free of moral bullying and his tone a model of open-mindedness and respect. (He indulges a more combative side in his newspaper columns.)

Sowell, 69, grew up in North Carolina and Harlem, and received degrees from Harvard and the University of Chicago. He's the author of "The Vision of the Anointed," a discussion of America's liberal elites and the way they picture the world. If, like me, you're a cranky liberal frequently dismayed by how rigid, blinkered and narcissistic liberals can be, you're likely to find the book a delight. Sowell spoke to Salon Books on the phone from Los Angeles, where he was on tour to promote his 26th book, "The Quest for Cosmic Justice," a fleet and pleasing three-essay treatment of how our dreams of fixing the world from the ground up can, and usually will, backfire.

You make a provocative distinction in your new book between "cosmic justice" and "traditional justice." Would you explain that distinction?

Traditional justice, at least in the American tradition, involves treating people the same, holding them to the same standards and having them play by the same rules. Cosmic justice tries to make their prospects equal. One example: this brouhaha about people in the third world making clothing and running shoes -- Kathie Lee and all that. What's being said is: Isn't it awful that these people have to work for such little rewards, while those back here who are selling the shoes are making such fabulous amounts of money? And that's certainly true.

But the question becomes, are you going to have everyone play by the same rules, or are you going to try to rectify the shortcomings, errors and failures of the entire cosmos? Because those things are wholly incompatible. If you're going to have people play by the same rules, that can be enforced with a minimum amount of interference with people's freedom. But if you're going to try to make the entire cosmos right and just, somebody has got to have an awful lot of power to impose what they think is right on an awful lot of other people. What we've seen, particularly in the 20th century, is that putting that much power in anyone's hands is enormously dangerous. It doesn't inevitably lead to terrible things. But there certainly is that danger.

Can you give me another example?

Yes. I had a teacher when I was growing up as a kid back in Harlem in the '40s who used to make us write every word we misspelled 50 times and bring it in the next day along with our homework. This is on top of the other homework we had. So if you misspelled two or three words, you were in for a long evening. Now, that was unfair. It was unfair because there were kids on Park Avenue, for instance, who were familiar with newspapers and books that used those words, and who had a much better shot than we did at knowing what those words meant and how they were spelled. But correcting that larger unfairness was never an option. It was never on the table. What was on the table was whether you were going to make these kids -- us -- meet standards that were going to be a little harder for us to meet. Or whether you were going to have make-believe fairness instead, and send us out into the world unprepared and foredoomed to failure. It seems to me the latter option is infinitely worse.

What's the allure of liberalism?

It means different things to different people. I suspect that at least half the people at the Hoover Institution were on the left -- liberals and in some case radicals -- in their early 20s. I include myself. One reason is that you simply want to save people who haven't received cosmic justice. You would like to see that rectified. And it's only with the passage of years that many people finally understand that life doesn't work that way. But there are other people, I think, who get a personal sense of worth and sometimes superiority from their liberal vision of the world. And they're not going to give that vision up easily.

So you were a lefty once.

Through the decade of my 20s, I was a Marxist.

What made you turn around?

What began to change my mind was working in the summer of 1960 as an intern in the federal government, studying minimum-wage laws in Puerto Rico. It was painfully clear that as they pushed up minimum wage levels, which they did at that time industry by industry, the employment levels were falling. I was studying the sugar industry. There were two explanations of what was happening. One was the conventional economic explanation: that as you pushed up the minimum-wage level, you were pricing people out of their jobs. The other one was that there were a series of hurricanes that had come through Puerto Rico, destroying sugar cane in the field, and therefore employment was lower. The unions preferred that explanation, and some of the liberals did, too.

Did you discover something that surprised you?

I spent the summer trying to figure out how to tell empirically which explanation was true. And one day I figured it out. I came to the office and announced that what we needed was data on the amount of sugar cane standing in the field before the hurricane moved through. I expected to be congratulated. And I saw these looks of shock on people's faces. As if, "This idiot has stumbled on something that's going to blow the whole game!" To me the question was: Is this law making poor people better off or worse off?

That was the not the question the labor department was looking at. About one-third of their budget at that time came from administering the wages and hours laws. They may have chosen to believe that the law was benign, but they certainly weren't going to engage in any scrutiny of the law.

What that said to me was that the incentives of government agencies are different than what the laws they were set up to administer were intended to accomplish. That may not sound very original in the James Buchanan era, when we know about "Public Choice" theory. But it was a revelation for me. You start thinking in those terms, and you no longer ask, what is the goal of that law, and do I agree with that goal? You start to ask instead: What are the incentives, what are the consequences of those incentives, and do I agree with those?

I notice that in New York liberal circles, people generally prefer arguing over ideals to discussing what might work.

Being on the side of the angels. Being for affordable housing, for instance. But I don't know of anybody who wants housing to be unaffordable. Liberals tend to describe what they want in terms of goals rather than processes, and not to be overly concerned with the observable consequences. The observable consequences in New York are just scary.

You aren't a fan of rent control?

No, I'm not. A figure I ran across recently that struck me as illustrating the moral bankruptcy of rent control is this: The number of boarded-up housing units in New York City is four times the number of homeless people on the streets. To think of that! On winter nights there are people sleeping on the cold pavement and dying of exposure, when there are these buildings that are boarded up as a consequence of economic protectionism.

I know you're usually referred to as a conservative. Do you think of yourself that way?

I don't. Because if by "conservative" you mean trying to preserve something from the past, I have no particular reason to do that. Right now, the public schools as they exist I would not want to conserve. There are other things I would want to conserve. But conserving something just because it's there has no appeal for me.

What would your preferred label be?

I prefer not to have labels, but I suspect that "libertarian" would suit me better than many others, although I disagree with the libertarian movement on a number of things -- military preparedness, for instance.

Is being a black libertarian tough? What are the assumptions people most often make about you?

Being a liberal or a conservative or a Marxist has never made that much difference in my life. I've never been someone who was courting popularity. I was a Marxist during the height of the McCarthy era.

You do have a knack.

[Laughs.] I missed the trend.

What's it like for you on the right? I certainly have met racist Republicans. I ask this question for the Salon readership, many of whom are probably convinced that the Republican party is made up entirely of racists.

That's not true, of course. It's amazing, for example, how many people on the right have for years been up in Harlem spending their money and their time trying to help the kids, including one whose name would be very familiar to you. But he hasn't chosen to say it publicly, so I won't either.

What are the biggest mistakes liberals make when they think about problems that afflict the black community?

One of their mistakes is to confuse moral issues with causal issues. People often attribute things to the legacy of slavery, for instance. But many of the things that are attributed to the legacy of slavery really were not as bad a hundred years ago as they are today. In the book I mention marriage rates and rates of labor-force participation. Another example is from Washington, D.C. A hundred years ago, there were only four academic high schools in Washington, D.C., three white and one black. There were some standardized tests administered, and the black high school came in ahead of two of the three white high schools. Now, it was certainly true, at that time and for a long time after, that Washington was a racially segregated and racially discriminatory town. But those clearly weren't the only controlling factors. I happen to have followed that particular school on into the 20th century. From the late '30s into the mid-'50s, the student body of that school ranked at or above the national average on IQ tests.

The passage of the '64 Civil Rights Act is usually viewed as one of the great events of the century. Not by you?

Of course there were things that needed to be gotten rid of -- the Jim Crow system in the South. My point is that people expected social and economic results which were not to be expected from that source.

What happens is that there's a sweeping under the rug of black success that does not fit the ideological vision. Just recently I learned about a black man named Paul Williams. This man became an architect back in the 1920s. He was told, "Your people don't have enough money to buy houses and build buildings, so you're going to have to depend upon white people for a living, and white people are not anxious to have a black architect." But he dealt with it, and in the '20s he began to make a name for himself. As the years went by he built homes for various celebrities and wealthy people -- Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, Cary Grant. He was part of a team that designed a building at the Los Angeles airport. For decades he was successful.

Now, no one wants to talk about him. Why wouldn't they want to? Because if you talk about him it knocks the props out from under the vision of why blacks are where they are. If it's all due to racism, how was this man able to succeed? Was it really just dumb luck?

Similarly, when I studied that high school, which became known as Dunbar High School in later years, I was naive enough to think that -- because everyone was talking about the problems of black education, what can the government do to bring good education to black kids, etc -- people would be eager to hear about it. I was saying, here's a place where there has already been outstanding education for blacks for 85 years. Well, I was totally wrong. I published my study, and it received very little attention. What attention it did receive was largely hostile attention from the black leadership community. Why hostile? Because it was of no use to them. It didn't justify new government programs, and it didn't show how the evils of white people were fatal to blacks. You just can't show people succeeding in ways that undermine the vision.

I've met black people with positions that can only be described as libertarian or conservative, who care very much about crime control and school vouchers, for instance. Any idea how many share these outlooks?

It's hard to say. There have been some polls taken. Certainly in the case of school vouchers, blacks are the group with the strongest support for them in the whole society. And the black leadership is almost 100 percent opposed to school vouchers. But the success or failure of the black leadership is largely in the hands of the white liberals. They have to go along to get along.

Was there at one point more of a mesh between the black leadership and blacks in general?

Well, there's no particular reason to think that the leadership of any ethnic group is going to be in sync with the actual desires of that group. Though it may be in that in certain time periods things do mesh better. In the '50s, for instance, there was a unanimity among blacks against Jim Crow that was not achieved before or since. But time went on, Jim Crow was defeated, and you got something you see in insurgency movements of all sorts, from early Christianity to the movement to create the Interstate Commerce Commission. The initial leaders of such insurgencies go in with very little to gain and a lot to lose. But once the insurgency succeeds, the people who were concerned about the problem tend to begin to lose interest, whereas for the people who are opportunists, now is the time to move in. You attract an entirely different type of person, and there's a change of leadership. When people complain about the decline in the quality of the civil rights leadership these days, I say, you know, if there were still 150 black people lynched every year, you'd have a higher quality leadership in the civil rights movement.

If you could knock a little something into the heads of young liberals, what would it be?

I'd like to get them to think in terms of incentives and empirical evidence, and not in terms of goals and hopes. Over the years, I've reached the point where I can hardly bear to read the preamble of proposed legislation. I don't care what you think this thing is going to do. What I care about is: What are you rewarding, and what are you punishing? Because you're going to get more of what you're rewarding and less of what you're punishing.

You write in the new book that only 3 percent of Americans spend as long as eight years in the bottom-fifth income bracket.

That study has now been extended to 15 years. And when you stretch it out to 15 years, you find that less than 1 percent of the American population is in the bottom income quintile for that duration. Add to that the fact that most of our millionaires have made their money themselves, and you realize that it's a tremendously fluid system.

People have a hard time getting used to the fact that there will always be a bottom fifth.

Some people just can't deal with it. In New Zealand, where I was giving a talk, I remember some leftist proclaiming, "We aren't going to accept people being in the bottom fifth!" [Laughs.] We're going to have to become like Lake Wobegon, where every child is above average.

If you could snap your fingers and make one big change in the country, what would give you the most satisfaction? What would really make a difference?

Do away with schools of education and departments of education. Close them down. There are fewer than 40,000 professors of education in this country, and 40 million students. That means we are ruining the education of over a thousand students in order to protect the job of each professor of education. I would think it would be one of the greatest bargains in history for us to give each professor of education $1 million to retire.

Are departments of education a complete write-off?

They're worse than that. They filter out highly intelligent people from the whole profession, because highly intelligent people are not going to put up with the Mickey Mouse courses that you have to take to enter the field. And once you filter these people out you're not going to get them back in again. People talk about how we ought to raise the salaries of teachers. To me, this is like buying expensive equipment to fish for ocean fish in an inland pond. If they're not there, nothing you do is going to bring them there.

Are you in favor of school vouchers?

I'm for any form of choice, whether it's vouchers or tax credits or charter schools. It's interesting, by the way, that the most childish letters I receive in response to my newspaper column come from teachers.

What do they complain about?

Any coherent answer I give you will misrepresent them because they're so incoherent. They seem to think that they can simply make up their facts, and that they can psychoanalyze me. They like to tell me, for instance, "You must have had a bad experience of teachers." [Laughs.]

What's most disappointing for you about the current right wing?

If you think about the Republican party, it's the complete failure to articulate their position. I think the government shutdown was their greatest fiasco. Republican congressmen would come on the air and they'd start talking about OMB figures and CBO figures. Good heavens, man! Republicans complain that the media don't get them. To me, what that means is that when you do get a chance on the media, you prepare yourself so you can really deliver a big punch. Instead, there was Dole floundering around, and congressmen talking about OMB figures. They really don't know how to communicate. In one of my columns I asked readers to name two articulate Republicans besides Ronald Reagan and Abraham Lincoln. And I don't recall anyone naming them.

Do you credit Clinton with anything?

I credit him with being the most consummate politician in perhaps the entire history of the United States. I find it hard to think of anybody who could have survived what he's survived. That's nothing to celebrate, though, because what he has done has permanently harmed the image of this country. But in terms of political craftsmanship, he has all the things that the Republicans lack.

Shares