Sometimes it's just good to know you're not alone.

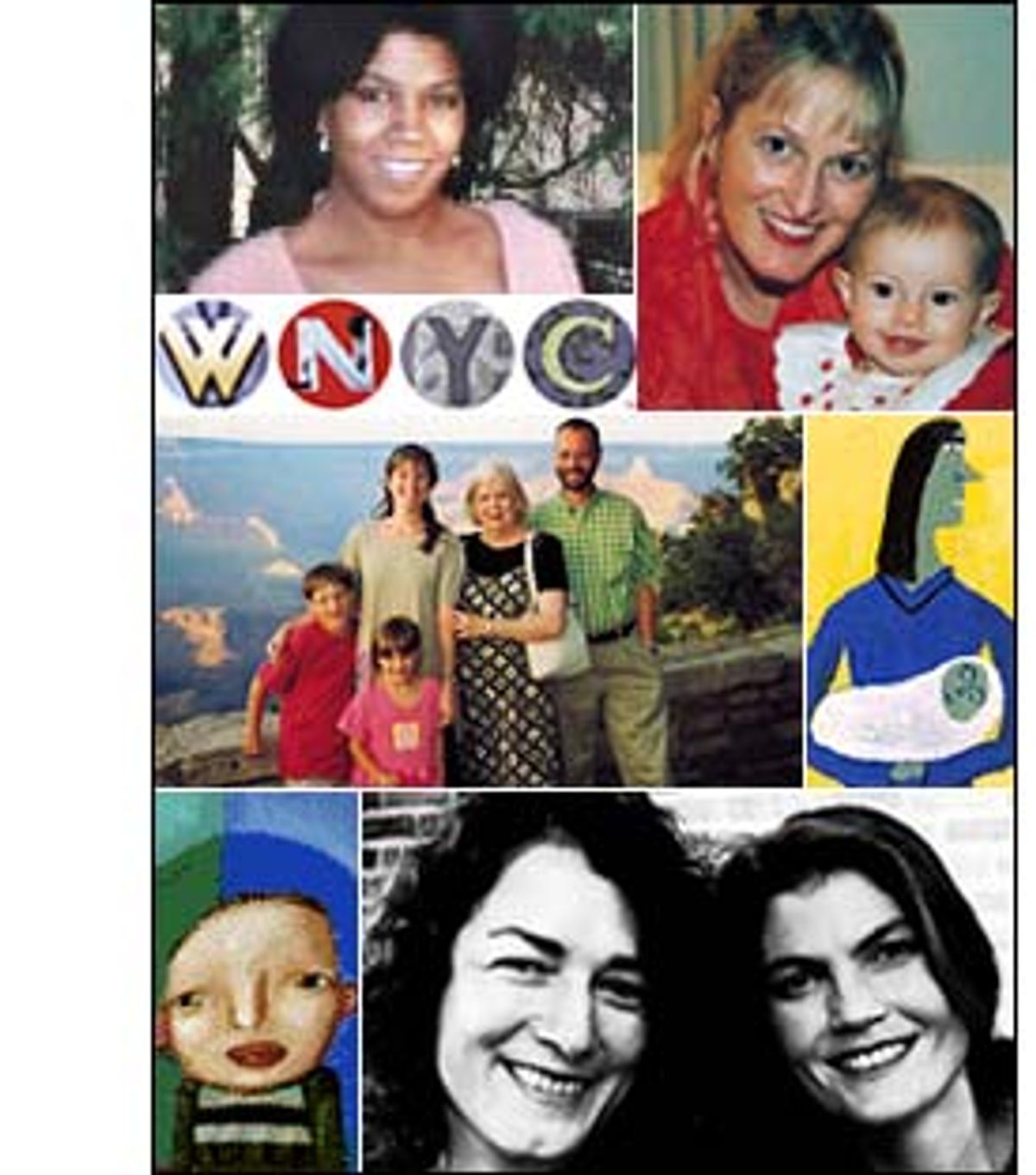

That's the theory behind The Juggling Act, an ongoing chronicle on New York's public radio station, WNYC. The series explores the ways men and women navigate -- or struggle to navigate -- between their jobs and their families.

The editors of Salon.com's Mothers Who Think and WNYC invite you to tell the boss to hold on for a minute, ask the kids to wait for soccer practice, and join us in honoring the juggling act that we perform everyday.

Throughout January, five contributors to Mothers Who Think will broadcast their commentaries on WNYC's The Juggling Act.

Here on Salon.com, you can listen to the essays, interact with the Mothers Who Think writers, and learn more about the topics covered in the series:

Cecelie Berry | Writer living in Montclair, New Jersey. Contributor to Mothers Who Think.

Cecelie Berry | Writer living in Montclair, New Jersey. Contributor to Mothers Who Think.

"Mrs. Satterfield was our housekeeper when I was growing up. She was black and from Mississippi. I was eight years old when she caught me daydreaming over multiplication tables."

Read more | Talk to Cecelie | Listen

(You need RealPlayer7 to listen to this commentary. Click here to download it free.)

Kate Moses |

Kate Moses |

Founding editor of Mothers Who Think, Co-editor "Mothers Who Think: Tales of Real-Life Parenthood."

"Mothers who work part-time soon find that Helen Gurley Brown's curse on the modern woman, the tiresome catchphrase "you can have it all," has transmogrified into "you have to do it all."

Read more | Talk to Kate | Listen

(You need RealPlayer7 to listen to this commentary. Click here to download it free.)

Jennifer Bingham Hull | Contributor to Mothers Who Think. Articles have appeared in the Atlantic Monthly, the Wall Street Journal and Ms.

Jennifer Bingham Hull | Contributor to Mothers Who Think. Articles have appeared in the Atlantic Monthly, the Wall Street Journal and Ms.

"Take two adults who are used to getting eight hours of sleep, going out to dinner, and even having regular sex -- deprive them of all of those things overnight and you get a relationship that's a bit ragged around the edges."

Read more | Talk to Jennifer | Listen

(You need RealPlayer7 to listen to this commentary. Click here to download it free.)

Camille Peri | Founding Editor, Mothers Who Think,

Camille Peri | Founding Editor, Mothers Who Think,

Coeditor, "Mothers Who Think: Tales of Real-Life Parenthood."

"When my sister-in-law discovered she was expecting a baby boy, her coworkers at a national liberal magazine offered their condolences. "That's too bad, one male editor sighed, you must be really disappointed." In fact she wasn't."

Read more | Talk to Camille | Listen

(You need RealPlayer7 to listen to this commentary. Click here to download it free.)

Elizabeth Rapoport | Executive editor at Times Books/Random House, Contributor to Mothers Who Think.

Elizabeth Rapoport | Executive editor at Times Books/Random House, Contributor to Mothers Who Think.

"I'm a working mom, and I feel guilty. Guilty because I can't always be there for my kids. Guilty because I think going to work is Club Med

compared to staying home with small children."

Read more | Talk to Elizabeth | Listen

(You need RealPlayer7 to listen to this commentary. Click here to download it free.)

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The Juggling Act is funded by a grant from The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and is created in partnership with Mothers Who Think, Salon.com and WNYC:

Cecelie Berry Commentary

Most of the nannies and housekeepers who sustain family life in New York

come from impoverished countries or disadvantaged backgrounds. As part of

WNYC's on-going work and family series,"The Juggling Act," Commentator

Cecelie Berry reflects on her relationships with these women and finds that

there is power in getting over the guilt.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Mrs. Satterfield was our housekeeper when I was growing up. She was black

and from Mississippi. I was eight years old when she caught me daydreaming

over multiplication tables. I had readied myself for a talking-to when she

leaned her gray head next to mine. "How do you do that?" she whispered.

I knew then that what I was often told was true: I was a very lucky black

girl.

Carrying that knowledge, and the accompanying guilt, I wasn't much good at

playing "Miss Ann." As a young lawyer, I didn't do the hiring, so like many

women, I first became an employer when I hired a nanny. The nannies I

hired came from Panama, Jamaica, Israel, Sweden, France, England, Ghana and

the United States. Though the cultures changed, the tactics of the power

struggle between mother and nanny remained the same. The motherlode of

guilt I carried from childhood made me -- "How you say?" -- dead meat every

time.

To topple me from my high horse, some nannies allowed me no privacy. After

the birth of my second child, my Panamanian nanny let my two-year-old son

enter the bathroom when I was showering. After an appraisive glance, she

later remarked on how some women's body's just "fall apart" after

childbirth.

Failing to sow the seeds of personal insecurity, some try to engineer

marital discord. One American nanny asked, "Did your husband give you

something nice for Valentine's Day?" At that moment, my mouth was filled

with chocolates, so I offered her one. Not satisfied, she continued, "Did

he give you some new jewelry when the baby was born?"

Another power play occurs when the nanny adopts a

"What-have-you-done-for-me-lately?" attitude. Whatever it is, it's not

enough. Georgette was from Ghana, and one day she asked if I still had a

recent New York Times. There was an article about her country and she

wanted to read it. I explained that I had already taken the recycling to

the curb. She seemed angry and I felt bad. So the next time I saw an

article about Ghana, I put it on the refrigerator, where it hung for several

days untouched. She never mentioned it.

Not every nanny is a sinister Mrs. Danvers, but they are rarely the kindly,

simple souls that we pretend. In our homes, they attain a degree of power

that few have in their own lives; we offer them a unique opportunity to

inflict the same systematic devaluation they themselves have suffered.

Often I overheard my Swedish au pair tell my children, "Mommy's too busy for

you." I made excuses for her, but one day, I realized there was no excuse.

My guilt finally flew right out the window.

I've been an at-home mother for six years now. While I'll never forget Mrs.

Satterfield's hopeless shrug seconds after I attempted to explain

multiplication to her, now this memory challenges me to take control of my

children's wellbeing. Perhaps the greatest power parents have is the power

to protect our children from those who are embittered or indifferent. It is

one that -- for the short time that we have it -- we should exercise liberally.

Juggling Act main page | Talk to Cecelie | Listen

(You need RealPlayer7 to listen to this commentary. Click here to download it free.)

Kate Moses Commentary

For many mothers who want to go back to work outside the home, part time work seems to be the key to a manageable life. In WNYC's

on-going series on work and family life, "The Juggling Act," commentator Kate Moses says working part-time offers mothers the

illusion of time without actually giving them enough of it to improve their lives.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Mothers who work part time soon find that Helen Gurley Brown's curse on the modern woman, the tiresome catchphrase "you can have it

all," has transmogrified into "you have to do it all." On paper, the trade of time for money seems straightforward, but in practice you may

be getting pinched in more places than just your wallet. Did your professional responsibilities really shrink with your paycheck, or will

you start feeling like the "I Love Lucy" episode at the candy factory, with Lucy shoving chocolates down the front of her uniform because

she couldn't keep up with the conveyor belt?

At home, there are often more expectations placed on you -- both consciously and subconsciously -- once you've cut down your hours

elsewhere. The delegating, outsourcing and takeouting you took in stride when you were working full-time rarely make the same sense

when you've downsized your income and, at least theoretically, got more time. My own fantasy is that after I neatly end my early workday

to pick up my children after school, I'll spend the afternoon supervising art projects or heading for the park or thumbing through Pottery

Barn catalogs. In reality, my older son does his homework in the car in the grocery store parking lot while I drag his little sister through

our weekly shopping odyssey. Later, at home, I can't relax. I'm too busy cleaning -- since I fired the cleaning service -- or making dinner --

since we can't afford anything but the occasional pizza -- or organizing PTA events I now feel too guilty to ignore. Or I'm dragging all the

unread Pottery Barn catalogs out to the curb.

The part-time dilemma is this: When you're at work, no one takes you seriously because they know by virtue of your part-time status that

you've put your family ahead of your career. Then at home, you're expected to do the lion's share of household maintenance since you've

"got the time." Meanwhile, the playground culture dismisses you as a "part-time mother" because you have another life at your job. If you

work part-time, you're working just as hard to please everyone but you don't get any respect.

So why am I still working part-time? It's that dream of time that I crave -- a dream fueled by the siren song of a part-time schedule. Time is

a working mother's most precious resource; tenaciousness and eternal optimism are her most well-worn tools. If I can't stop time, I'm

determined to pause it occasionally. So I cling to my unlikely goal of a fulfilling career combined with afternoons of loafing with my kids.

I might make myself sick trying, but I won't have to call in sick if I succeed.

Juggling Act main page | Talk to Kate | Listen

(You need RealPlayer7 to listen to this commentary. Click here to download it free.)

Jennifer Bingham Hull Commentary

Nobody talks about it. And you won't find many books on the subject in the parenting section at Barnes and Noble. But commentator Jennifer Bingham Hull says having a baby is a bomb on your marriage. Her comments are part of WNYC's on-going work and family series, "The Juggling Act."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

My once happy marriage was rocky for at least a year after the birth of our daughter, Isabelle. How could it be otherwise? Take two adults who are

used to getting eight hours of sleep, going out to dinner, and even having regular sex -- deprive them of all of those things overnight and you get a

relationship that's a bit ragged around the edges.

Previously equals, you and your husband suddenly operate from completely different frames of reference. He doesn't worry about whether he's

spending enough time with baby. He's changing so many more diapers than his Dad did that he can't help but feel superior, even if he isn't changing

nearly as many as you are. And everybody else is complimenting him too.

You, however, can't win. You may take time off work but you'll never put in as many hours with Baby as your own mother did. Then there's your

career. Once an efficient piece of machinery you could rely on, your brain is suddenly clogged with tiny baby needs - things your husband doesn't

even seem to notice. He taps away on his computer with that same old single-minded focus. You start to write a client and think: "buy Desitin." He

packs his bag for vacation and brings a novel for the plane. You pack two bags and put Cheerios, wipes and Winnie the Pooh in your purse for the

flight. And when your spouse finally does change that diaper and says, "Honey we're out of Pampers," you explode.

He's right. You have become a shrew.

It occurred to me after I followed my husband, Bill, down the block, giving him instructions for his walk with Isabelle, that maybe, just maybe, I was

being a bit too controlling. And I realized that by being controlling, I was teaching my husband incompetence.

So I backed off. Asked whether to put on her red or blue dress, I answered: you decide. I let Bill feed Isabelle all the "wrong" food and go around in

wet diapers on his shift. And I asked him to get her in the morning. Soon, Isabelle began calling for Daddy upon waking. And suddenly, Bill

offered to get Isabelle every morning.

Look, therapy is expensive. The only way to really have it all is to share parenting. It's not easy. He has to learn to multi-task beyond the confines of

his car. You have to give up control. Which is to say, women have to change more.

But when you finally arrive in that foxhole together, he as tired as you, baby wailing at 2:00 AM, again ... and when he rises and grumbles "I'll get

her" -- and you let him -- you realize, that's commitment, that's love.

Juggling Act main page | Talk to Jennifer | Listen

Camille Peri Commentary

A generation ago, Rogers and Hammerstein penned parental sentiments like "You can have fun with a son but you gotta be a father to a girl."

Commentator Camille Peri says the current "crisis of boys" gripping the nation shows that, somewhere along the way, we stopped having fun

with our sons and started policing them.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

When my sister-in-law discovered she was expecting a baby boy, her coworkers at a national, liberal magazine offered their condolences. "That's

too bad,"one male editor sighed. "You must be really disappointed."

In fact, she wasn't. But in the current American landscape, boyhood is considered a blight, a plague on all our houses. On the parenting

bookshelves, titles like "Cherishing Our Daughters" and "Raising Strong Daughters" beam out brightly next to "Lost Boys: Why Our Sons Are

Violent and How We Can Save Them," or "Boys Will Be Boys: Breaking the Link Between Masculinity and Violence."

Play weapons, shadow boxing, finger guns have mysteriously become predictors of future violence. Once these were the stock and trade of boys'

fantasy play. Now they're frowned upon or banned at most schools, along with the ideals of heroism, adventure and manliness that went with

them.

In the rush of cultural analysis that follows tragedies like those in Littleton and Columbine, all boys become guilty by association. The common

mantra is that media violence and computer games are "conditioning" boys for violence. But millions of dollars in research has failed to produce

more than marginal link to immediate aggressive behavior. And, clearly, the overwhelming majority of boys who watch TV and play video games

do not become violent criminals.

"Boys are in silent crisis," William Pollack, the author of "Real Boys," warned last year. "The only time we notice is when they pull the trigger."

Never mind that boys are pulling the trigger in diminishing numbers. Despite the widely publicized wave of campus shootings, school violence

of all kinds has been on a six-year decline, according to the Centers For Disease Control and Prevention.

The boy-crisis industry conveniently ignores realities like these. It also ignores the many cultural signs that boys are changing for the better.

"Animorphs," the book and television series widely embraced by boys, features cool boy heroes who are strong but also vulnerable. Pokemon,

the most recent mega-phenomenon in the Power Ranger-Ninja Turtle genre, is also the least violent: Its "warriors" are pudgy, pocket-sized

creatures like Jigglypuff, whose "sing attacks" send "even the toughest Pokemon to dreamland."

As a mother of sons, I don't see a generation of lost boys. What I see is the forming of a new Boy Code that could be called sensitive macho. My

nine-year-old likes to pretend that he's the machine-gun toting Keanu Reeves character in "Matrix" AND that he's one of Brittany Spears' male

backup dancers. He's fiercely competitive at soccer but not afraid to cry. He'll proudly burp the entire "Star Spangled Banner," then smother his

little brother with hugs and kisses. The boys I see are not docile or disturbed -- they are exuberantly integrating a smudgy softness into their

masculinity.

Isn't that what we really want for our sons?

Juggling Act main page | Talk to Camille | Listen

(You need RealPlayer7 to listen to this commentary. Click here to download it free.)

Elizabeth Rapoport Commentary

We've all heard about the so-called Second Shift-working moms who race home after a long day at the office to log in another four hours of childcare. As part of WNYC's on-going work and family series, "The Juggling Act," Commentator Elizabeth Rapoport considers herself an

elite member of the Third Shift--working moms who also slave into the wee hours of the night, overcompensating for time away from their

kids.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

I'm a working mom, and I feel guilty. Guilty because I can't always be there for my kids. Guilty because I think going to work is Club Med

compared to staying home with small children. Guilty that I can't keep upwith the PTA moms.

Lord knows, I try.

The second shift moms call it a day once the kids are in beds. Wimps. That's when we third shift moms are just kicking into high gear. You

know our kind. We're up until midnight downloading educational handouts for our kids' classes, writing school newsletters, phoning, planning,

collating, sewing. We're up at five A.M. to bake cupcakes for the bake sales. The weekends are a blur of soccer games, Girl Scouts, and

"Mommy and Me" activities. We are not well.

Of course we should downshift. Of course we should stop feeling guilty--working moms give our kids positive role models, pay the mortgage,

blah, blah, blah. But it isn't easy. We need help.

I propose GuiltEnders, the l2-Step Program for Guilt-Impaired Working Moms:

Step l: I admit that I have no control over my life, just as I have no control over my family photo dump.

Step 2: I believe that a power greater than myself can restore me to sanity. That power is the trinity of coffee, K-Mart, and the pizza delivery man.

Step 3: I will make a decision to turn over my life to the care of God as I understand Him. But I do not understand why He invented head lice,

nor why He sent our kids home with them.

Step 4: I will take a fearless inventory of myself. I will not do this naked.

Step 5: I will admit to others the exact nature of my mistakes. I will do this over and over and over.

Step 6: I declare I am ready to have a higher power remove all these defects of character. I will transfer them to my husband, coincidentally also a

working parent. Let him organize the Rootin' Tootin' Rodeo Read-aloud.

Step 7: I will humbly ask a higher power to remove my shortcomings, preferably through liposuction.

Step 8: I will make a list of all persons I have harmed, including the next stay-at-home mom who says, "You work? I wish I could, but I could

never leave my kids with a stranger."

Step 9: I will make amends to anyone I've already hurt, including co-workers I've forced to buy Nutty Buddy Bars, ugly gift wrap, and fundraiser

plush toys of chirpy school mascots.

Step 10: I will continue to take personal inventory. I will say "no" to sewing any Halloween costume that involves both fake fur and zippers. I

will refuse to sit on any steering committee, unless I am sitting and steering a yacht.

Step 11: I will engage in daily prayer and meditation. I will do this in the bathroom, where the kids can't find me.

Step 12: I will spread the good word by helping others with their addiction to overcompensation. Even though I know that if you're a working

mom, you won't listen.

Shares