Let's get one thing straight: The murder charge filed against Michael Skakel last week is not part of the Kennedy tragedy.

The only tragedy belongs to the parents of Martha Moxley. On Oct. 30, 1975, the Moxleys sent their 15-year-old daughter out for an evening of Halloween pranks in Belle Island, a hyper-privileged gated enclave amid the general affluence of Greenwich, Conn. The next morning she turned up dead, beaten with a golf club belonging to their tony Republican neighbors the Skakels, stabbed through the neck with its handle. Martha's body, half-stripped, was dragged to a shrub on her parents' property 150 yards from the Skakel residence.

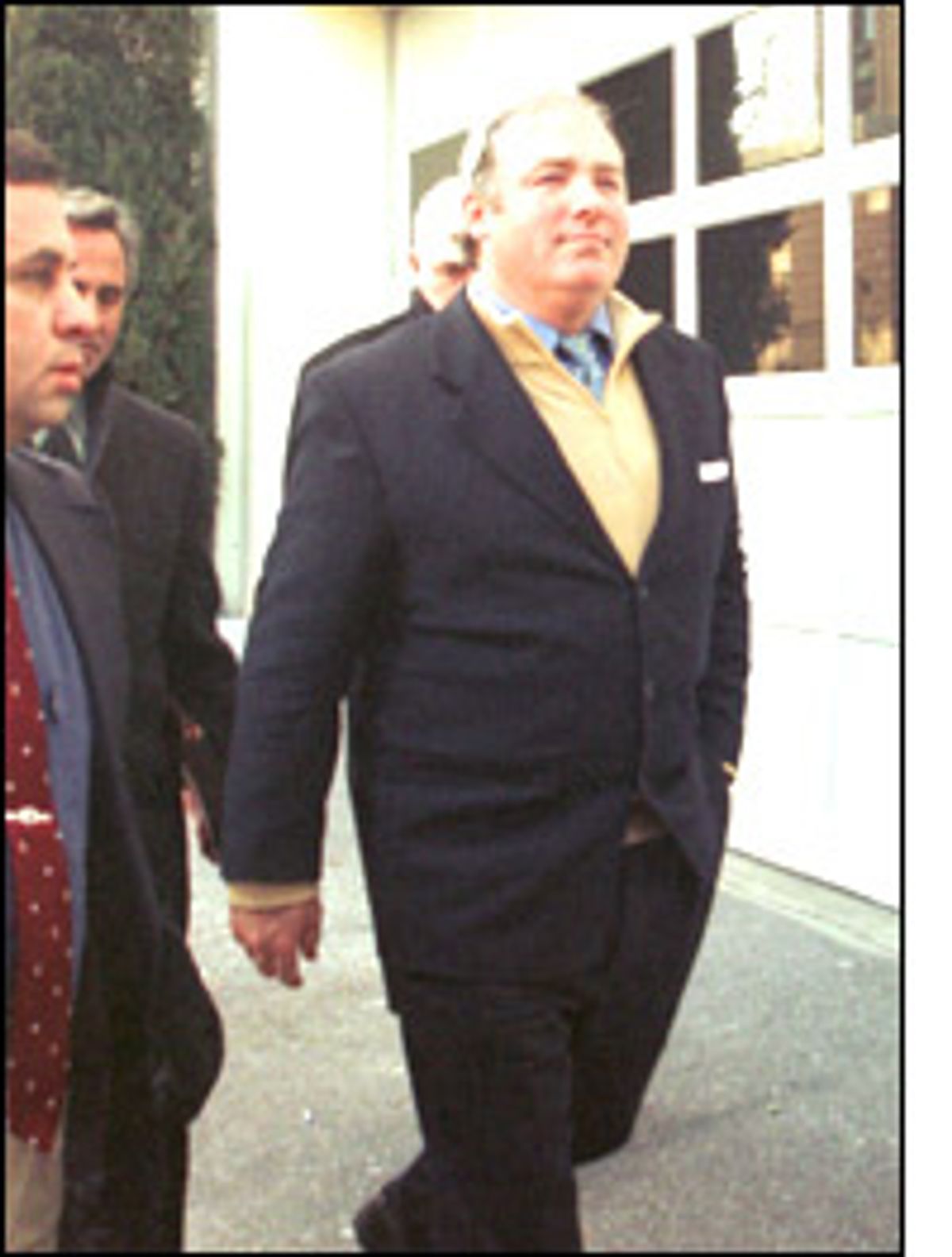

Now, in the strangest turn of a strange case, 39-year-old Michael Skakel -- whose aunt Ethel married Bobby Kennedy -- has been indicted for Moxley's murder: indicted, that is, in juvenile court, because he was only 15 at the time of the crime. Michael Skakel and his brother Thomas were among the last people to be seen with Moxley alive; she stopped by their house prior to her killing. With no precedent in Connecticut law for such a long-delayed trial, it is possible that Skakel's entire case will be heard in those confidential juvenile-court chambers. At the very least it will take up to a year for prosecutors to pry the Moxley murder trial into an open adult courtroom.

The irony here is that middle-aged Skakel suddenly makes juvenile court a hot media subject. He becomes the best-publicized juvie in history, at a moment when American juvenile offenders are more likely than any time in the last 100 years to be tried, sentenced and executed as adults.

For a useful comparison, consider Nathanial Abraham of Pontiac, Mich. After he shot Ronnie Green in 1997, no one offered Abraham the sanctuary of juvenile court -- even though he was just 11 years old at the time of the crime and "too small for the shackles used at his arraignment," as the Detroit News reported. Instead, he was tried as an adult and convicted in October 1999 of second-degree murder. The prosecutor who convicted him won reelection a few weeks later promising yet more "tough justice."

Abraham -- whose mental capacity has been tested at three years younger than his biological age -- was spared life behind bars only by a compassionate and courageous probate judge, who on Jan. 10 refused to impose an adult sentence. Declaring the law under which Abraham was convicted "fundamentally flawed," Oakland County Probate Judge Eugene Moore instead sentenced the boy to juvenile custody until age 21, decrying legislators for "diverting more youth into an already failed adult system."

Or talk to the father of Rodney Hulin, sentenced in 1995 to eight years in an adult prison after confessing to arson at age 16. "Dad, I'm really scared, scared that I will die in here," he wrote. Hulin was repeatedly raped and beaten by older inmates, finally hanging himself in January 1996. "Sending young children to adult prisons will not make our streets any safer," his father told Congress last year. "Sending children to be beaten, raped and robbed does not deter crime."

Despite dissenting voices such as Judge Moore and the elder Hulin, in the six years prior to Michael Skakel's juvenile-court indictment, 40 states passed laws allowing the prosecution and incarceration of children as adults: full-scale assault on the juvenile court system first conceived by social reformer Jane Addams in Chicago in 1899.

It is an assault inspired by well-publicized prophecies in the early 1990s from two criminal statisticians, James Alan Fox of Northeastern University and John DiIulio of Princeton, of a massive upsurge in juvenile crime by a new generation of cold "super-predators" -- "jobless, fatherless juveniles," in DiIulio's phrase. Instead, the juvenile homicide rate fell, the super-predators never appeared and DiIulio is now calling for an end to the endless expansion of prisons.

But the political popularity of punishing children continues undeterred by reality -- as George W. Bush knew in 1998, when he executed Joseph John Cannon and Robert Anthony Carter, both for crimes committed when they were juveniles. (The U.S. is the only country on earth to allow execution of juvenile offenders, and Texas has executed two-thirds of them.) The Cannon and Carter families would probably have appreciated some of the consideration shown to Skakel, whose name was not even officially released by Connecticut's courts law week, lest the confidentiality laws governing juvenile charges be violated.

Don't get me wrong. I am glad that even 24 years later the teenage Skakel of 1975 will get all the measured compassion that the juvenile court system has to offer -- and that the adult Skakel of 2000 gets the presumption of innocence.

But it is also worth pondering a double standard of accountability that seems to be at work: While most of the country is writing off youthful offenders, some of America's most privileged are rushing to plead juvie. It's only a short leap from tough-justice Rep. Henry Hyde dismissing an affair in his 40s as "youthful indiscretion"; from tough-justice presidential candidate Bush rushing teenagers to lethal injection even while shrugging off his own "youthful irresponsibility," to middle-aged Skakel enjoying the privileges of juvenile court.

When and if his case ever goes to an open adult courtroom, you can be sure that a Connecticut jury will hear all the genuine troubles of Skakel's gated-community youth: the death of his mother and absence of his father, the drugs, the alcohol, the despair amid massive affluence.

It is also worth pondering this: If Michael Skakel indeed killed Martha Moxley, he had a lot of help keeping his secret. The conspiracy would have extended well beyond his immediate family, and well into adulthood. There were, for instance, his classmates and teachers at the Elan School in Poland Spring, Maine, a rehab center for troubled, substance-abusing and extremely well-heeled teenagers (tuition, room and board $44,000 per year in 1998, with no financial aid available). Skakel was frogmarched to Elan three years after Moxley's murder, for trying to run down a police officer while driving drunk in Windham, N.Y.

Based on the grand jury investigation that led to Skakel's indictment last week, it would appear that Skakel's friends at Elan, now in their 30s and 40s, heard something from him bordering on a confession about Moxley's death. But those classmates kept their silence -- at least until subpoenaed in 1998 by Judge George Thim, the investigator under Connecticut's unique one-person grand-jury system. And they were not the only ones in the Belle Isle protection racket. The Elan School's faculty and administration, aided by Skakel's lawyer, Michael Sherman, spent months in 1998 trying to fight off Thim's subpoenas under the cloak of "confidentiality" -- a confidentially finally tossed into the ashcan by the Connecticut Superior Court more than a year ago, laying the groundwork for last week's indictment. This is a crowd that could teach the Sopranos a thing or two about omert`, but nobody seems ready to file a RICO case.

If Skakel's murder indictment is not another chapter in the Kennedy Tragedy, it is even less evidence of a Kennedy Curse. The only curse is that Skakel evaded arrest 24 years ago for precisely the same reason that the killer of JonBenet Ramsey remains at large today in Boulder, Colo.: The Greenwich cops, accustomed to protecting the rich rather than busting them, bungled the investigation in its early hours, failing to secure a search warrant for the Skakel premises. The only curse is that in Belle Isle, as in Boulder, the rich are so successful at evading the normal procedures of justice.

Shares