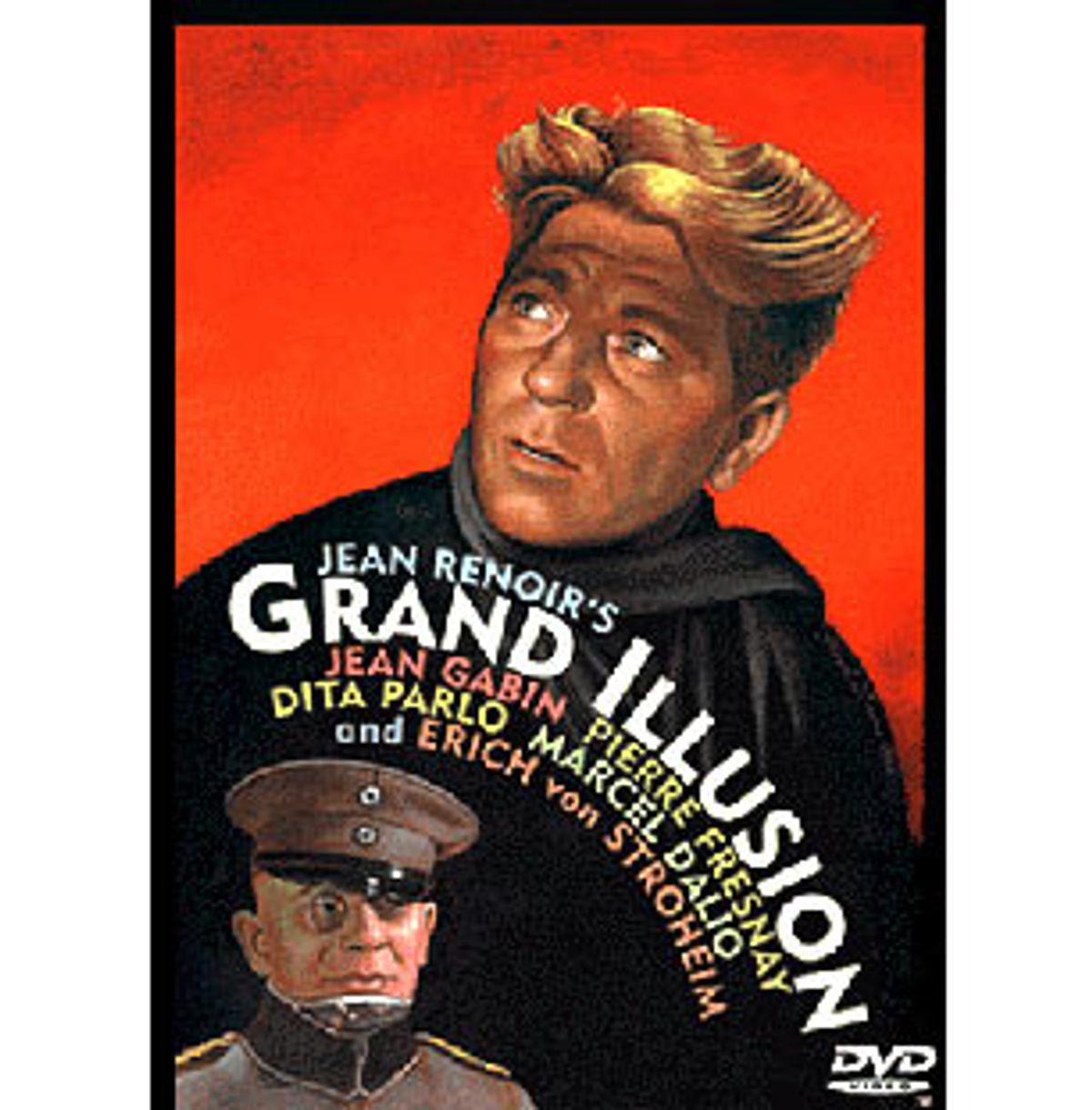

This year the National Society of Film Critics, in an unprecedented move, gave its best picture award to a pair of movies: "Topsy Turvy" and "Being John Malkovich." But just as unusual was the four-way split the society came up with for its film heritage award, created "to recognize extraordinary achievements in film preservation and restoration:" the theatrical release of the rediscovered camera-negative print of "Grand Illusion" and the newly preserved director's cut of "The Third Man," the video and DVD releases of the original version of "The Passion of Joan of Arc" (long thought lost to fire) and the cable broadcast of an expanded version of Erich von Stroheim's truncated epic "Greed."

The Criterion Collection -- the New York company known for its primo laser discs -- has issued all except "Greed" on DVD. Unlike other classy cultural providers that couldn't react to the marketplace and eventually disappeared (remember Command Records or Atheneum books?), Criterion deduced in the mid-'90s that DVD would swallow up laser and be bigger than laser ever was. In the fall of 1997 the company announced plans to launch a DVD line in early 1998 -- and, two years later, has released 66 titles in the fast-growing format.

In an age when home viewing is the norm for fans of classic art films, Criterion has whet appetites for optimum picture quality and stylish and intelligent packaging. As a pioneer in laser, Criterion introduced stay-at-home movie-lovers to the delights of letterboxing and audio commentaries -- things few top-of-the-line DVDs from any company now go without.

The producers of Criterion DVDs haven't just followed the trail they blazed in laser disc -- they've broadened it. They've taken advantage of the new format's flexibility to gather even more materials that augment rather than merely hype a movie. These include both the obvious and the esoteric -- from the original coming-attraction trailers to pithy background talk by filmmakers and scholars, rarely seen documentaries and deleted footage, displays of script pages and source material, interactive essays and even original mini-documentaries of backstage stories.

Yet there's no library mold on the Criterion Collection. It's frisky and gleefully eclectic. This is one art company that will prize a benchmark "mockumentary" as highly as any auteur masterpiece -- and imbue its disc with the same giddy sense of rediscovery. Criterion's double-sided "This Is Spinal Tap" disc contained separate commentaries on the movie by both the band members and the filmmakers, and beyond that tossed in lost scenes that were as funny as the ones kept in the movie, including more with Billy Crystal and his mime-staffed catering service and a hysterical additional sequence with Bruno Kirby, the Sinatra-obsessed chauffeur, who spends an evening with the band and winds up stoned and singing "All the Way" in bikini underwear.

The three-disc set commemorating Terry Gilliam's nearly buried "Brazil" is the ultimate in jazzy reconstruction, including the 94-minute studio cut; a 142-minute "final final cut" edited, for the first time, just the way the director wanted it; and a video documentary on Gilliam's nightmarish fight to release the movie his way -- written and narrated by Jack Matthews, whose column for the Los Angeles Times provided the forum in which Gilliam and his studio antagonists took their stands.

Robert Towne once called Jean Renoir "the greatest filmmaker" and said of "Grand Illusion" that "it's difficult to extract technique" from a film so large and so full of love, irony, wit, reality -- life. It's a measure of Criterion's desire to balance form and content that its producers voted "Grand Illusion" to be the symbolic first entry in its DVD line. Criterion, along with the French film company Canal Plus, can take credit for reactivating the abandoned quest to find and restore the original camera negative. And along with Rialto Pictures, Criterion helped put glorious new prints of "Grand Illusion" into American theaters last summer.

The director of the Criterion Collection, Peter Becker, and its CEO, Jonathan Turell, are the sons of William Becker and Saul Turell, who were partners in Janus Films -- the art house distributors who from the late '50s through the 1970s combined good taste and savvy snob appeal, importing contemporary European classics films for budding American cinephiles, and in the process making the names Bergman and Fellini passwords into higher movie culture on every major campus in the country.

During its laser disc days, I wrote liner notes for 10 Criterion productions, less for the modest fees than the opportunity to play a part in the creation of a home-viewing world that echoed the art houses of the '50s and '60s. But when I interviewed Becker by phone recently (he called from his office in Midtown Manhattan), it was the first chance I'd had to talk to him extensively about the company and his plans for it. On the two-year anniversary of Criterion's entrance into DVDs, we discussed its experience packaging films as different as Ozu's "Good Morning" and the rather less-acclaimed movie that was the subject of my first question.

One Salon reader in the Table Talk string called "How to build a quality DVD collection" wrote that he was "inclined to say the best way to build a superior DVD collection is to get whatever Criterion has released. Well, except for 'Armageddon.'"

The answer to that person is "Thanks" -- but also, "to each his own." There are always titles in the collection that people single out. We're just beginning to get across the idea that we're a collection, and when you do that you're always going to get people who say, "How could you include this or that?" Part of the joy of following a collection is to take part in the controversy.

Specifically, with "Armageddon": You'd be silly to overlook blockbusters as a genre and leave them out of a film library. They drive so much. They drive tastes and shooting styles and visual references that appear all over the world in commercials and on TV as well as on movie screens. They're part of a huge cultural cross-pollination. And special effects are one of the most important aspects of a certain kind of contemporary filmmaking.

The opportunity we had to explore the effects in "Armageddon" was extraordinary. These guys dug a 400-foot hole in the middle of a Hollywood sound stage. It was a mammoth project and a great thing to be able to chronicle. One may choose to say, "What an enormous amount of money to spend on so frivolous an enterprise." But it occupies an important position on the spectrum of contemporary films.

Michael Bay, who made "Armageddon," is one of the most masterful directors of that kind. He's managed to develop a certain style and energy in shooting that is consonant with what people seem to be looking for in these huge blockbusters. He's an articulate exponent of what he is up to, and he is refreshingly candid. He's not going to sit there and try to convince you that his and Ingmar Bergman's intentions are one and the same. He's trying to make a wild ride and he's trying to show you how it's done.

While it may be that there are some who feel it's uncomfortable to see "Armageddon" on the shelf next to "Amarcord," they're both great discs for different reasons. I think there's an honorable place for "Armageddon" in our collection. It may help us bring in a whole new audience. If we climb too proudly to the top of the ivory tower where we screen only Fellini and Bergman, Godard and Truffaut, Kurosawa, Tarkovski and Pabst, we will find ourselves very soon preaching only to the choir.

Part of the strength of our company is that we can make a disc that will put "Nights of Cabiria" or "Grand Illusion" in front of somebody who may not even know it has a reputation as one of the great films. Look, we caught a lot of flak when we first did "This Is Spinal Tap" on laser.

With each release we're dedicated to finding a film that is exemplary of its type and to making the best possible disc from it. We caught a lot of flak for doing "Seven" with David Fincher, who is one of the most amazing natural talents behind the camera, one of the smartest, sharpest minds, and an amazing guy to work with. On the other hand, we also found a lot of people who were happy to find our quality and style of work being done on behalf of that film.

Is there a commercial imperative for you to do films like "Seven" or "Armageddon"? Does it pay for "The Passion of Joan of Arc?"

It's not as if one thing pays for the other. Well, maybe it is to a certain degree, but we would never make that trade-off. If there's something that we don't want to do, we won't do it. This place is in spirit democratic -- our producers have a strong impact on what we produce and how we produce it. Their names are the top line on each release. And they have, if not total creative control, at least creative direction of each release they work on. They essentially dedicate themselves to a film or group of films one at a time.

For example, one producer's working on an Eisenstein restoration set now. When a new title opportunity comes up, there has to be a producer who's willing to take it on, personally. Sure, we were never worried that "Armageddon" wouldn't return the cost of producing it -- it was at the time the highest-grossing live-action movie that the Disney company had ever distributed. So the commercial prospects of the property were probably relatively safe, particularly because the main capacitors of sales are the buyers for the major chains, who are certainly more aware of "Armageddon" than they are of, say, Reni Clair's "A nous la liberti." One walks away from profitable activities at one's peril, but there was, honestly, never any concern that we'd walk away from "Armageddon."

Even people who hate "Armageddon" have to admit that one of the best things about your collection is that it's not stuffy. In addition to the high art, it's got some glitz, and it's got some cult items.

In that vein we are just finishing up work on what is going to be a landmark edition. It's a two-disc set of the cult horror film "Carnival of Souls." We've got both Herk Harvey's later director's cut and the original theatrical release (which is also sort of a director's cut). There is validity to both versions and different film on the two and since it can't be programmed in a way that you can play one or the other, we're presenting both, with tons of supplements.

That's a film that desperately needed to be done right, because it was always treated as public domain, with a million different versions out there. We worked closely with the screenwriter [John Clifford] who survives and was Herk Harvey's partner. Harvey made industrial films for the rest of his life for a company called Centron in Lawrence, Kan. This one picture is his landmark. We went into that release with the same degree of reverence and excitement that we'd go into working on "The Third Man." If we don't feel that we can do it right and well, we just can't do it.

Speaking of "The Third Man": As a fan of the director Carol Reed, I love that on your DVD of "The Third Man" you have Welles' friend, Peter Bogdanovich, do an on-camera talk in which he says that it really is Carol Reed's film, not Welles'. It's like the dictum in politics, "Only Nixon could go to China."

Peter was the only one who could disown it as an Orson Welles film and declare it Carol Reed's show.

In terms of how you present those and other extras -- there's no dictatorial editorial voice telling a viewer how to go from one feature to another. You present us with a wealth of materials and in some ways ask us to create our own program guides.

We want to lead people into these films and give them areas to romp around in afterward. The viewer's mind is a free mind; why would you want to cage it up? We try to reach into film archives all over the world and take treasures that are buried in basements that you need credentials to get into and allow home viewers to put them on their shelves. It's a great privilege for Criterion to be able to go and poke through what exists in film archives -- but poking around is part of the fun that we should pass along. We'll definitely err on the side of including things that might be of marginal interest to some people if we think they may be of essential interest to others.

I'm thinking, in particular, of "The Passion of Joan of Arc" disc. The goal was to create something definitive that would present the film in a way that would attract new viewers, which it has. When you dig through the disc there's a lot of content that's sophisticated enough in its analysis of the different versions of the film, and the history and context of the film, that it will stand up to the scrutiny of scholars. We're very conscious that we contribute not only to people's home collections but to libraries and universities. When we do things that have an academic as well as a consumer attraction, we have to pass muster.

I think we've accomplished most of what we set out to do in our first two years in DVDs, which is carry over the Criterion sensibility into a new format and figure out how to employ that format intelligently. In many ways the greatest contribution we've made over the 15 years we've been doing this is raising people's hopes and expectations of what watching a film at home can be -- and then trying to live up to that standard.

But is there a danger to getting people too comfortable with spectacular home video presentation? Even sophisticated fans don't seem to understand that improving a movie on video doesn't mean that any restoration or even preservation work has been done to the original film.

At Criterion, we've always thought that we should leave a movie we've worked on in better condition than we found it in. In one sense, that means we try to present our films as the filmmakers would want them seen. That means in uncut and uncensored versions, in their proper aspect ratios, with ancillary materials that will enhance not only viewers' understanding and enjoyment of the film, but also their desire to see it again and look deeper into it.

But we also recognize that filmmakers really want their films to be seen in a dark room with a lot of other people, projected from some distance away, on celluloid. When we have an opportunity to restore and reissue a film theatrically, bringing it back out in front of audiences, we do that. The difference between what we do and what Bob Harris does when he restores "Lawrence of Arabia" or "Rear Window" -- though the goal is the same, to present a pristine print of a great picture -- is that Bob really wants to create a stable, secure, even permanent physical picture element. We all hope it will last, but he's working with an ephemeral medium that needs proper temperature storage and other stuff.

Still, you can't beat film grain! It's the most beautiful recording surface for moving images. Our works exists finally on a digital tape. The movies are stored in bits. Strictly speaking, in terms of film restoration, the film may not be restored. But it is at least preserved and recorded. We shouldn't underplay the importance of these things just because the final product for restoration isn't a piece of film. It's probably more stable and certainly in a format more accessible to an array of people than a piece of film permanently stored in an archive vault. That's not to say that we shouldn't be giving money to film preservation. Everywhere we look we find that films have been recorded on volatile material and there is a great deal of restoration and preservation work that needs to be done.

Now, when we go through and do restorations for video only -- and we're very clear that we're not actually restoring the film -- we tell people that the image has been restored and we show them examples of the repairs that we do so that we can educate their eyes. We want them to know what a splice looks like. What we do is go back to the best possible preprint elements that we can, then we create a digital record of those elements.

In the case of "The Seventh Seal," even when you find the best possible element -- which was just a revelation, a stunning, beautiful piece of film -- it had tears, it had scratches, it had all kinds of things that would be very difficult to get rid of prior to making a theatrical print, because you'd have to find replacements for those frames and match them and time them into a new element and all that. Digitally, it's relatively easy for us, because of the material we invested in here for our specialized work, to go in and repair a tear or a scratch or a section that needs special attention. Often the heads and tails of reels, where the reel changes, tend to be where the film gets beat up.

We do these repairs in our offices, on a Silicon Graphics rig set up with a brilliant piece of software that was designed by a company called Mathematical Technologies -- just a very smart and single-minded digital image restoration system. It does incomprehensible amounts of math in order to generate algorithms that will compare the elements of past and future frames to the damaged frame and mathematically interpolate what actually ought to be in that frame. It's not infallible; we end up using a very light hand with it.

If there's something that can't be repaired in a way that we feel that we feel is ideal -- i.e., imperceptible -- then we'll leave it. Same thing goes for sound restoration, which we do with a great system designed by a company called Cedar. There are certain kinds of problems that are almost impossible to repair imperceptibly and then we'll have to leave them. And that's true in actual film restoration as well. There's always the one that got away.

"Grand Illusion" is one of the best examples of the work you do spilling over into actual film preservation and restoration -- also of how the problems of banning and censorship intensify the challenges of film restoration, since they make it even more difficult to find decent renditions of a director's preferred version.

The short form of the "Grand Illusion" story is: Basically, the film was declared cultural public enemy No. 1 of the Third Reich by [Joseph] Goebbels. Largely that had to do with the close friendship it showed between the character played by the French everyman movie star Jean Gabin with a Jew. Of course, there were also notions of undermining and overthrowing the German order. I'm sure none of those things played well with Goebbels.

So when Paris fell and the Nazis marched in, the negative was seized and everyone believed that it was immediately destroyed. But in fact it was spirited away to the Reich film archive and there fell into the hands of Dr. Frank Hensel, who, at least when it came to great movies, was more of a loyal ciniaste than a Nazi. Despite orders that "Grand Illusion" be destroyed, he hid it away.

After the war and the partitioning of Berlin, the film element we are talking about turned up in the Russian sector. Nobody believe it existed, everybody believed it had been destroyed back in '42 when the Nazis first walked in. So nobody was really looking for it. It went back to Moscow and sat there. From 1958 until 1998-'99, when we finally re-did it, there was a blurring on the right side of the frame on all the available elements of "Grand Illusion."

Correcting it wasn't a matter of digital restoration -- it was a matter of getting to the right element, which turned out to be this original camera negative. The blurring was made in an intermediate stage in the printing process, when a duplicate negative was struck that became the master element for the 1958 reconstruction of the film. That blurring in the right side of frame was in everything we looked at for the last how-many years.

In '96 we started seeking new film on "Grand Illusion" because we wanted it to be our first DVD. The spine on the DVD still says that it's No. 1 even though it came out after 65 others. It is spiritually, the first DVD of the Criterion Collection. Our first picture on laser was "Citizen Kane"; when it came time to do DVD we knew we wouldn't launch until a year after the DVD roll-out. What were we going to do? What would be the first one? We all democratically kicked this around and voted and all this stuff and many heated run-on conversations and everyone finally rallied behind "Grand Illusion."

Why didn't you do "Citizen Kane" again?

"Citizen Kane" is at Warner and we didn't own the rights or anything. And we never wanted people to believe that Criterion on DVD was simply going to be a replica of Criterion on laser. The collection is a living entity and constantly growing. When we did "The Third Man" on laser disc there were no supplements at all. We could have slavishly followed our old policy and put "The Third Man" out on DVD with no supplements but that would have been a dull thing to do.

Anyhow, on "Grand Illusion," we made two trips to France but really weren't happy. We were getting a better picture because the transfer process had improved since the last time we had handled the elements: We were seeing better grays and blacks and finer contrasts. But we were still seeing a lot of the artifacts that were the result of the 1958 release. Then we got this call from the Cinimathhque Frangaise saying that they had pulled in a bunch of films from the Cinimathhque Toulouse and that they thought they had something we would want to see.

We went over, hung it up, took a look, and there was the original camera negative of "Grand Illusion," with Russian leader on it. It had clearly been taken care of, though it had passed through all these hands. It was a piece of World War II history and cinema history. And it was an amazing moment, almost as if you had put your finger on a socket and all of a sudden all the circuits were buzzing all at once.

Because of this huge historic find, everyone agreed that this thing needed to be out in the theaters. Now I get to look at a beautiful Paul Davis poster of "Grand Illusion" and every time I see it be reminded that we had something to do with bringing the film back in front of people the way it was meant to be seen.

What projects are you working on now?

We're trying to determine what the right course of action is with "Gimme Shelter," which is going to have its 30th anniversary this year. It'll be back out in theaters the end of the summer. That's a film that is not in jeopardy, but has never gone out uncensored. And it's especially strange to have a piece of cinima-viriti, something out of the direct-cinema documentary movement, come out with bleeps in it.

Audio repair work has been done on it, but it was never married to film before. And you get into the whole audio question: the standard array for speakers in a theater has changed since a lot of these films were made, and there's an open question as to how one should handle certain kinds of films.

Do we think it was a good thing or a bad thing that "Yellow Submarine" came out in Surroundsound? There are lots of purists who would say it is a bad thing on principle, because that's not the way the film was originally released. On the other hand, the alternative argument says, if one can be faithful to the original intentions of a piece and make it more suitable for the current viewing environment, that might be the way. For us it ends up being a question of in general erring on the side of safety where subjective considerations are concerned -- there's nothing more frustrating than going to see something that is purportedly restored and hearing things that you just know are wrong.

We ask the question all the time: Does this need to be remixed? If it does need to be remixed, is the sound designer alive? In the case of "Picnic at Hanging Rock," it was Peter Weir's baby beginning to end. He's the one who helped us make that decision and said absolutely, let's do it. He thought the soundtrack was essential and should permeate the entire film and should fill the theater. He thought it would be better all-in-all if we went back and created a new Dolby Digital mix and took advantage of the new technology.

On the other hand, we're not about to pick up Reni Clair's "Le Million" and, just because it was an early sound-period film, split it into five channels. That's just wrong. When you cross the line from restoration and preservation to something else is the question. But I'm not sure that "something else" is inherently evil. One has to be honest about what one is doing.

And you have to be sure that somewhere the original will still exist.

Exactly. We want to raise awareness of what conditions these things are in out in the world. As people watch DVDs they expect to see a perfect digital image. People forget that these things are in trouble. When we put something out from a pristine element that didn't need any monkeying around with, I'll get a letter about a hair in some frame, with the frame number. It's like complaining about a Rembrandt because it has one of his eyelashes stuck in it -- or saying that if we make a postcard of it we should at least take that eyelash out.

In "Spartacus," we're looking at a scene where there's a light leak in the top of the camera -- and what do you do about that? I still don't know whether to fix the light leak. Kubrick couldn't for film when he made it; but for us on video it is relatively easy to do. I find it distracting but it is with great trepidation that I would go mess with it. It's a mechanical medium. I think people should get used to seeing that kind of thing -- and stay a little bit used to seeing the imperfections -- because it reminds you that way back there is an original piece of film.

When you see a piece of printed-in dirt on a piece of film (and generally we try to remove almost everything we can find that is at all distracting), in a way it's a reminder that there is one piece of film that passed through the camera that was being looked at through the eye piece by one of the world's great directors.

Just as there's only one "Mona Lisa," there's only one camera negative of "Grand Illusion" and only one existing print of Carl Theodore Dreyer's original version of "The Passion of Joan of Arc." And then there are many films that have been completely lost. People can become fanatical about wanting crisp clarity -- to the point where I also see that there's a subset of people who are annoyed by seeing film grain, which is part of the essence of film.

When we make DVDs, we try to preserve a sense of the grain even though we know that by the time it is fed through your television set it is nothing more than an impression of the texture of the film. That impression is important, and it's easy to wipe out -- just crank up your noise reducer and it will turn everything into television. This is not television, it is film, and that grain has its own elegant dance to do on your screen.

What has been the response to your up-market pricing? [Most Criterion releases retail at $29.95 and $39.95.]

It's been our pleasure to be able to be substantially closer to the market price than we were on laser. Our stuff on laser was about on a 100 percent premium compared to other discs; we were priced between $50 and $150. That was partly a factor in the difference in cost between lasers and actual DVDs. Now we're only about 10 bucks above market -- as far as street pricing goes, that may mean paying $23.95 instead of $18.95 -- and that's about as close as we'll ever be able to be.

But in the end we're putting so much work, research, actual money into making new film elements where necessary, doing digital restoration work, acquiring supplementary material, that we really have no choice but to share the cost with the people who are building their home collections. One of the challenges is to get people to come to the collection for the first time, because once they come they tend to come back. Over time they find that some percentage of their shelf is Criterion discs and that they like the way that shelf looks.

It's expensive to offer real value. We don't want to find ourselves in a position where we're cutting corners because there's no margin to support the work that we do. Part of the love of it is being able to do it right. On the one hand, if we were a huge deep-pocketed studio we might be able to write off any losses for particular releases on a line that would vanish in a corporate report.

In reality we're a small private company and we've got to float on our own. But in a large corporate environment it would be more likely for someone to ask "Couldn't you have done this without spending $15,000 on this new element?" The answer would be, yes we could have but the disc wouldn't have been as good. And it's important to uphold people's expectations.

Shares